REVIEW: In The Wild Duck, Dark Family Secrets with Ironic Humor

Quintessence Theatre’s production is problematic, but even the problems are interesting.

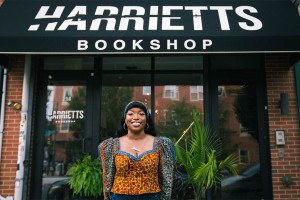

Tom Carman, David Pica, and Deysha Nelson in The Wild Duck at Quintessence Theatre.

Sins of the fathers visited on the sons (and wives, daughters, and everybody else). Dark family secrets, slowly and painfully revealed. Shockingly bad choices leading to catastrophic results. With these building block plot points—standard clichés of overwrought melodrama in lesser hands—Henrik Ibsen breathed new life into modern theater.

He did it by using old tools to make new points. Ibsen brought piercing psychological insights very much ahead of his time (more than a decade before Freud, in fact), coupled with an emphasis on ethical and moral questions. His greatest plays—A Doll House, Hedda Gabler, John Gabriel Borkman—feel startlingly fresh even today.

The Wild Duck was once thought of as one of these great plays, but its status has fallen, and the last Broadway production was nearly fifty years ago. It is, for sure, a perplexing mix. On the one hand, this story of two intertwined families and their complicated multi-generational legacies is unmistakable Ibsen territory, including its central theme of shattered idealism. On the other, it’s over-plotted and dense, and (as with other late Ibsen plays), elements of symbolism are introduced that don’t entirely cohere. And, though Ibsen is often the most earnest of playwrights, he’s also an experimentalist—The Wild Duck is rather curiously categorized as a tragicomedy, about which more in a minute.

Still, with all its oddities, The Wild Duck remains gripping and provocative, and worthy of production by the bold company willing to take it on. For this reason alone, we owe Quintessence our gratitude. Indeed, there are a number of good things here, though it’s a problematic production. But even the problems are interesting.

To start with, director Rebecca Wright has updated the action to a contemporary world that sounds and looks quite American. For some scenes, it’s a win. The opening party registers with gauche excess, and, at the other end of the spectrum, tense conversations between husband and wife—very well played here by David Pica and Brett Ashley Robinson—about their marriage and their daughter have real immediacy. The final ten minutes are truly shattering. In fact, they are reason enough to see this production.

On the other hand, 19thcentury Norway is, in large and small ways, a very different world from our own, and details of this world keep bumping into Wright’s production. Two supporting characters—a doctor (Mary Tuomanen) and a preacher (Julia Frey)—are re-gendered and strangely re-thought in ways that don’t make sense (though the two actors are, as usual, interesting to watch).

Then there’s the challenge of the humor. I have no doubt Ibsen can be funny—darkly hilarious in parts of Hedda, for example. But exactly how that works tonally is tricky. Perhaps I’d understand it better if I were Scandinavian, but in any case, I wasn’t persuaded here—the opening night audience often laughed at moments where I was mystified.

Some of this clearly came from the performers. Pica (playing the fragile and easily-influenced Hailmar) is a delightful actor, whose slightly off-center, slacker-ish charm has enlivened many Philly shows. He does so here, too, but his quirky charm is sometimes a distraction. Pica is much more effective in the second act. Likewise, Tuomanen’s deadpan line readings don’t always hit the right notes, though she, too, rises to the occasion in the final scene. Among the rest, it’s a generally able ensemble, and in particular, Deysha Nelson, a remarkably poised child actor, does exceptional work as Hedwig, a difficult role more often played by young-looking adults.

So a mixed bag—but a worthy and thoughtful one. And those last ten minutes will remain in memory for a long time.

The Wild Duck plays in repertory with Julius Caesar through April 29. For more information, visit the Quintessence Theatre website.