THEATRE REVIEW: Old Meets New and East Meets West in The King and I

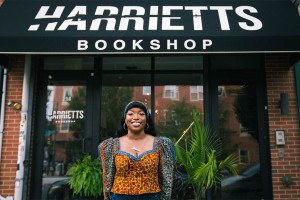

Laura Michelle Kelly and Jose Llana in The King and I at the Academy of Music.

Bartlett Sher, one of America’s busiest and most accomplished directors, has worked in every medium from straight plays to opera—but he’s won particular acclaim for two classic Rodgers and Hammerstein musicals that he revived at Lincoln Center. Before The King and I (now onstage at the Academy of Music) came Sher’s revelatory South Pacific. What was notable from the start was Sher’s approach—first and foremost, to fundamentally trust the material. He and his designers gave the show a beautiful frame; he also focused on the acting values inherent in both Hammerstein’s book and Rodgers music. Otherwise, Sher allowed the piece speak for itself, even when it creaked a little with age.

These virtues are immediately apparent also in King and I. Michael Yeargan’s gorgeous, jewel-toned scenery evokes the lavish Siam of exotic dreams—the arrival of the boat bearing Anna and her son Louis, silhouetted against a glowing red sky, is the first of many oooh-aaah moments. Laura Michelle Kelly, a lovely Anna, brings uncommon nuance to the sweet scene between mother and son. And the show’s big moments, including the procession of the King’s children, the fabulous “Small House of Uncle Thomas” ballet, “Getting to Know You,” and “Shall We Dance,” feel simultaneously fresh and comfortingly familiar.

Laura Michelle Kelly, Baylen Thomas, and Graham Montgomery in The King and I at the Academy of Music.

On balance, though, King and I doesn’t have the alchemy that Sher delivered in South Pacific. Some of the issues are directorial—I don’t think he displays the same level of imagination here. But much of it is inherent in piece. Though King and I postdates South Pacific, it has the look and feel of an earlier, stiffer kind of musical. More problematic still is the politics. The cultural clash of East and West—a theme that Rodgers and Hammerstein explored in several musicals—emerges here with the queasy sense that “enlightenment” is synonymous with Westernization.

Sher handles this exactly as I believe a contemporary director should—he portrays it unflinchingly, and expects that an audience will understand that the context was different then (King and I premiered in 1951). But I imagine some audience members will find parts of it tough to take. You might remind them that in its day, the show actually introduced aspects of Eastern culture to Broadway, and it was notable for having a strong heroine who stood up to the patriarchy. Also, that the King is a good man, wrestling awkwardly but heroically to move Siam into a more modern world. Actor Jose Llana makes him appealingly boyish, which charms the audience but also minimizes the sexual chemistry between him and Anna. (One directorial mistake here is to suggest that the King drops his whip before striking Tuptim because he’s stricken with a heart attack—the stage directions make it clear that it’s a pang of conscience that stops him, which is a stronger choice more aligned with the sympathetic message Rodgers and Hammerstein mean to convey.)

Or you can simply bask in the beauty of the score. It is the songs that were and still are the glory of King and I—and though they are heard here with a reduced orchestra that sometimes sounds puny, the music never fails to lift the heart.

Shall we dance? Yes, absolutely.

The King and I plays through April 2. For more information, visit the Broadway Philadelphia website.