INTERVIEW: Choreographer Justin Peck

From Ballet 422 (courtesy Magnolia Pictures).

There’s a powerful scene in Ballet 422, the 2014 documentary following New York City Ballet dancer and choreographer Justin Peck as he creates a beach-themed love story ballet “Paz de la Jolla.” The most cinematic moment unfolds after the then 25-year-old Peck, in suit-and-tie and his Clark Kent glasses, modestly takes a bow on stage as the audience enthusiastically applauds his new work. After his demure smile and wave, the camera follows Peck as he quietly heads backstage and proceeds alone to his dressing room to transform from wunderkind choreographer — out of his suit and glasses — into an anonymous corps de ballet dancer with make-up and costume. It’s a wonderful moment that captures a hard-working young man on the cusp of a brilliant career that promises to shape the future of ballet. Peck’s ordinary demeanor is a mask for his extraordinary talent.

It’s only been three years since the “Paz de la Jolla” premiere, but there’s been significant change for the dancer from San Diego. Peck was promoted to the rank of soloist in 2013. He was named resident choreographer in 2014, only the second person appointed to that position at NYCB ever. And he’s established himself as the future of classical ballet dance-making, injecting a dose of youth culture and hipster cool into the sometimes fussy world of ballet. Peck has drawn in the millennial set by collaborating with indie rockers Sufjan Stevens and The National; visual artists Marcel Dzama, Shepard Fairey, and Sterling Ruby; as well as edgy fashion designers Huberto Leon of Opening Ceremony, Mary Katrantzou, and Prabal Gurung.

Critics have taken note, too. Alistair Macaulay, chief dance critic for The New York Times, raved about him last year: “Mr. Peck has quickly become the most eminent choreographer of the ballet in the United States — and two particular characteristics have propelled him to the top: the exciting formal architecture of his dances and the kinesthetic thrill of his movement.” Macaulay also described Peck as: “The third most important choreographer to have emerged in classical ballet this century.” Not too shabby.

Now 28, Peck contributes his 2013 work, “Chutes and Ladders,” (set to music by Benjamin Britten) to Pennsylvania Ballet’s February program (running February 4-7). It also includes dances by Nacho Duato, Jerome Robbins, and Christopher Wheeldon.

Peck informed me he won’t be in attendance for Thursday’s opening night at the Merriam Theater because he will be in New York dancing George Balanchine’s “Symphony in C.” Two days prior to that, Peck will premiere his own 45-minute narrative ballet, “The Most Incredible Thing” at City Ballet. He’s spread pretty thin these days, but he found some time to talk with me by phone between rehearsals at Lincoln Center and a performance later that evening.

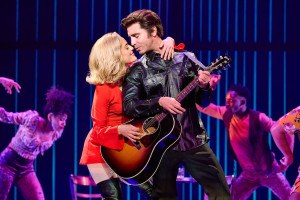

Justin Peck and Janie Taylor, The Block Magazine from Justin Peck on Vimeo.

In the documentary Ballet 422, you are caught in a moment of your career when you are both at the top and the bottom of the ballet pecking order. How did you manage your interactions with your fellow dancers during that time?

You’re right. It’s an interesting point in my development. It was a time when I was figuring out how to navigate a colossal institution. Working with dancers was the least of my issues. They are very humble and focused on the work being created — with very little ego. I’ve known a lot of them for many years and we have our own relationships so I’m able to pull a lot out of them because of that.

You are the company’s second resident choreographer following Christopher Wheeldon. Did Wheeldon offer advice on how to work with the dancers who you might also be dancing with?

No, Chris did not. He hasn’t been around too much since I started making more ballets. He’s very friendly and we have conversations about our work, but it’s a kind of desolate environment. There’s not a lot of guidance to go about making the dances. You learn through doing. Everyone has their own process. I will say I have learned a lot by being in a studio with different choreographers who come in and work with the company.

During the documentary, there’s a scene when you are in the lobby on opening night talking with two older patrons. One asks you how it feels to walk down the same staircase to the theater as did George Balanchine and Jerome Robbins. Was there a time when you’d stepped back and assessed how far and fast you’ve come in your career?

I don’t feel that distance, but when people say things like that it definitely puts thing in perspective. I try to do not let the pressure affect me. I put my head down and work. I do feel pretty ecstatic about it. I feel very lucky that there’s a good amount of people who respond to my ballets.

“Chutes and Ladders” was a piece you made for Miami City Ballet in 2013. How did you find its music, Benjamin Britten’s String Quartet No. 1 in D Major?

That whole project started because I was commissioned to make a piece for the Miami City Ballet for a special performance in collaboration with the New World Symphony. It had specific parameters about what the piece could be in length, scale of music, and cast size. I spent a fair amount of time searching for the right piece of music to use to create that dance. I discovered this pretty hypnotic piece by Britten and felt compelled to work with it. Most of the time I have the freedom to pick music and build a ballet outwards, but with this project it was in collaboration with such an esteemed music program, the New World Symphony, so there was some back and forth with its director Michael Tilson Thomas, until we landed on this one. It’s a strong piece for a ballet.

What do you think of Leonard Bernstein’s description of Britten’s music, by saying it sounds like “the gears not quite meshing”?

I haven’t heard that before. I do not agree with that. I found the work to be very hypnotic and showed great range and contrast. It’s very dynamic and goes back and forth between an introverted and extroverted quality. It’s brilliantly structured.

For our readers who haven’t seen the work, what should they look for?

The piece is an exploration of the range of a relationship between two individuals. It takes an audience on a journey. There’s a high level of intimacy and series of ideas that are explored and shared between them. The musicians are on stage for the duet. I’ve always loved it when musicians perform alongside the dancers on stage. It creates a different level of intimacy with the performance.

Did you and PB artistic director Angel Corella know each other from his time in NYC?

The ballet world is small, but I grew up watching him on stage and videos of him. I always really admired him. He had an electricity on stage, but he was already running his company in Spain when I started dancing at City Ballet. So our paths never really crossed in New York City. The first time we started to communicate was when he took over the Pennsylvania Ballet and he expressed interest in my work.

Will you be creating any future work for Pennsylvania Ballet?

I would love to come work with the company there if Angel is interested. Honestly it’s a matter of finding the time in my schedule and my capacity to take on work, because I have my residency at NYCB. My output takes priority with my own company. Every once in awhile I can sneak away and create a new work, but next year I’m not doing any outside commissions.

With all of your work demands as both a choreographer and a dancer, how much coffee are you drinking these days?

[laughs]. I enjoy a cup in the morning. My work is energizing enough.

February 4-7, Merriam Theater, 250 S. Broad Street, paballet.org.

HEATSCAPE a new ballet by Justin Peck from Justin Peck on Vimeo.