How This Philly School Pioneered a Revolutionary New Method for Learning

When parents send their children to school, the stakes and expectations run deeper than just hoping they learn how to pass a test. With students spending more waking hours at school than at home, they come to rely on their teachers for more than just facts and figures; school is where students are supposed to learn how to learn, where they start to grow into a life-long learner. At the end of the day, parents want their student to come home more confident, creative, and ready for future challenges.

But what if the standard public school education experience isn’t a good fit for your child? All too often, students who have not excelled academically in school have shouldered the blame for their lack of success. They’ve been given tutors and extra credit, and asked to try harder. However, this approach does not factor in different learning styles or needs, and getting a child special help in a public school setting can involve extensive legal paperwork.

Benchmark School, an innovative, co-educational school for children in grades 1 to 8, has developed an alternative approach for those students. Founded by educator Dr. Irene Gaskins in 1970, the school introduced a new model of individualized education that provides a better way to learn for children with learning differences, such as dyslexia or ADD/ADHD. The school was the first of its kind in the Philadelphia region, celebrating skills that went unrecognized in traditional school, and has since produced thousands of successful alumni who went on to higher education and had prosperous careers.

“We know that some children learn best when they process auditorily; we know that [other] children learn best when they process visually. We know that for some children, neither one is particularly strong, or there is something else going on there, so they need the whole package,” says Megan Wonderland, former Benchmark teacher and the school’s current director of admissions and enrollment management. “Our goal is to make sure that [the students] understand their learning style, so that they can ask for specific help and be an advocate for themselves. They’re the ones in the classroom on a daily basis. They’re the ones who need to be able to raise their hand and say to a teacher, ‘This isn’t making sense. Can you repeat that?’”

Recognizing a Learning Difference

The traditional public school model— with large class sizes and lack of individualization—can be a nightmare for students with learning differences. But for many parents, it can be difficult to identify that their child is struggling in school for several years—especially since many students aren’t conditioned to be active participants in conversations about their education.

“Our population tends to be a very bright population—and often the smarter they are, the better they are at hiding their struggles and finding defective coping strategies to survive in a classroom,” Wonderland says. She recalls one of her former students, who said he would sit in class and pay attention to the student sitting beside him, and turn the page in his book when the neighboring student did.

If a parent does suspect that their child may be struggling, there are a few red flags that it might not be the child’s approach, but the school’s. If the school has approached the student or parent about the student needing additional help, that’s a sign that something in the traditional classroom isn’t working. Another sign is problems with homework. If a child becomes very frustrated when doing homework or parents feel they have to reteach the material on a nightly basis in order to get through homework, this can be an indication that the instruction the child is receiving in the classroom isn’t connecting with them, no matter the effort they’re putting in.

In these cases, Wonderland recommends getting a second opinion from a psychologist or neurologist specializing in psychoeducational testing, or even a child’s pediatrician. Getting tested for a complete learning profile which can reveal dyslexia or other factors that impact learning can not only benefit a child in their public school setting, but it can also provide clear evidence that another school may be a better fit.

Forming the Right Environment

While Benchmark School requires psychoeducational testing for admission, Wonderland says, it’s not the “end all be all,” and some students attend Benchmark without any diagnosis at all, but rather a learning preference that isn’t being met at school.

This practice builds on Dr. Gaskins’ original mission, which was to use research and data to develop a new methodology that helps students thrive. As a young teacher, Dr. Gaskins was tasked with teaching “struggling readers” in an Individualized Education Program (IEP) service where students who needed extra help in certain skills could meet with educators in small groups. She was devoted to her students, but felt that the instructional model being used was not meeting their needs. This experience inspired her to found Benchmark School.

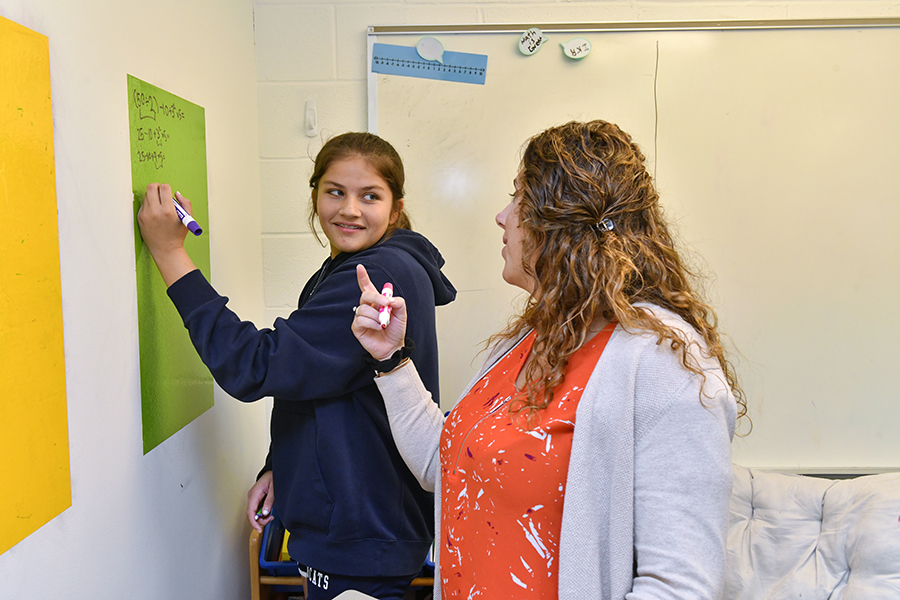

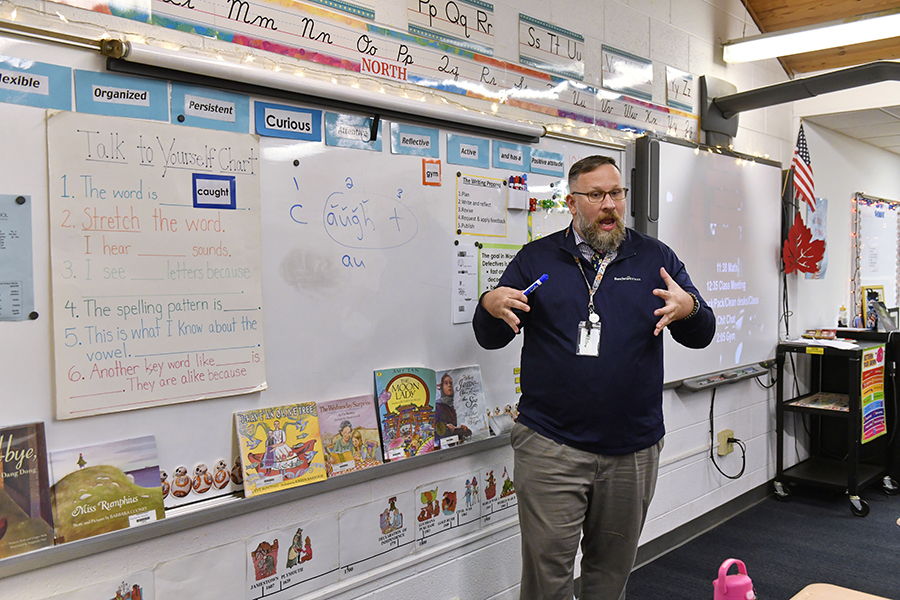

In the half-century since then, Benchmark School’s methodology has expanded to include different cutting-edge learning solutions like metacognition, pattern recognition, audio-visual learning and aspects of student-centered education.

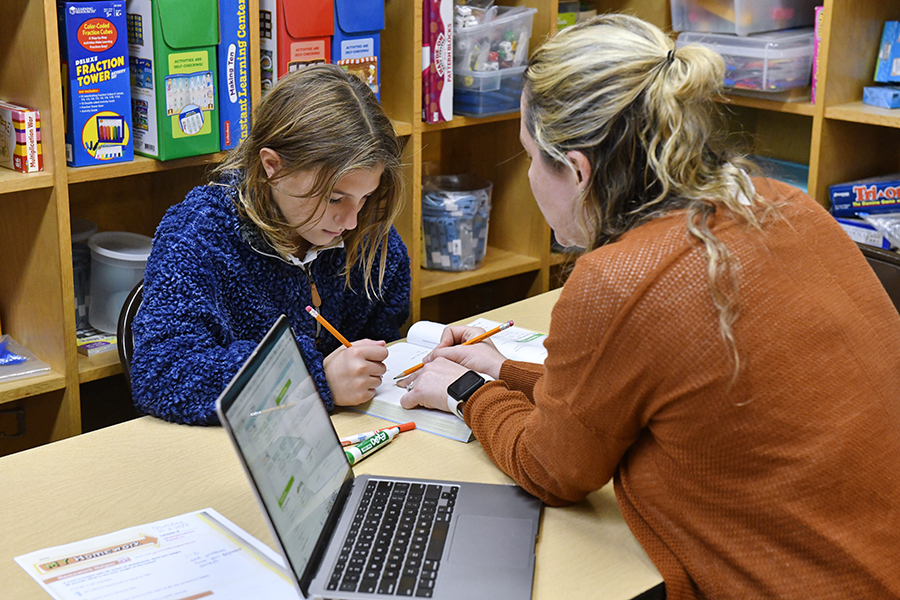

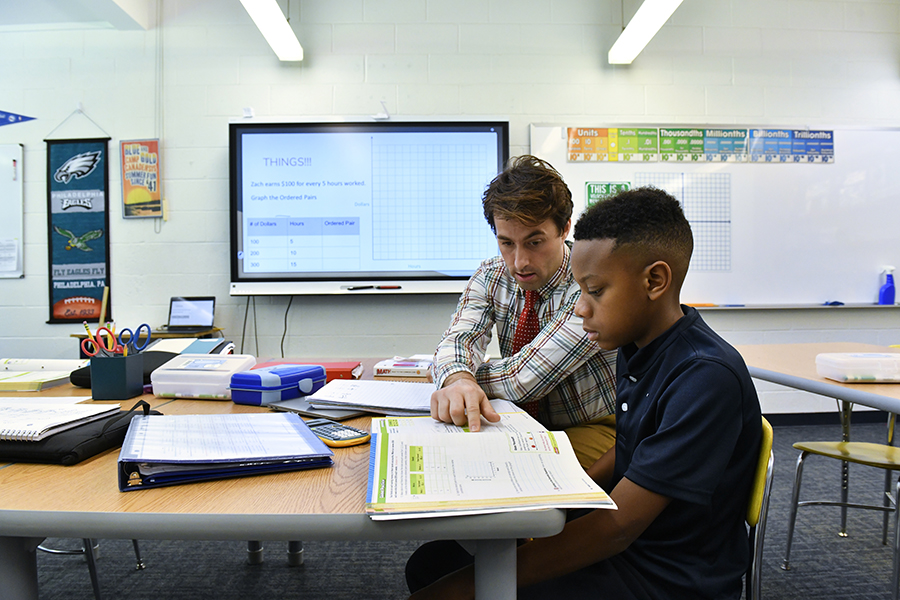

The educators at Benchmark School help students develop solutions and strategies for learning, rather than memorize correct answers. For example, instead of students memorizing vocabulary for spelling tests, they learn common patterns of words that appear in the English language and how to identify and use those patterns to read and spell. Educators regularly communicate with each other about what they have observed about each child in their own classes to create a holistic learning plan, rather than focusing on their own specific subject in isolation. So, if a student is blossoming in science class but struggling in language arts, their teachers may create a strategy plan with goals that uses their strengths from the former subject in lessons for the latter.

“Having the ability to have a whole team working together to have eyes on this child, and have discussions about this child, is really, really helpful,” Wonderland says. “We’re very big on strengths. It’s not just about what the child can’t do; it’s about what the child can do and what their passions are and what their strengths are, and how we can help them grow those things and use them to pull along the other things that may not be going as well.”

These personalized experiences are in part made possible by the small class sizes. The school has a one-to-seven teacher-to-student ratio, with two teachers assigned to classrooms of 13 students. The teachers get to know their students, and find opportunities to build learning into each part of the day—including gym class. It’s an approach that public school programs don’t always have the necessary resources to pull off. Public schools are more beholden to statewide budgets, curricula and standardized testing, whereas private schools like Benchmark can tweak their lessons in the moment to match needs.

Learning how to learn—whether it’s in gym class or math class—is also crucial to the Benchmark School experience. If students are playing a game in their gym class, the teacher may briefly pause in order to give students an opportunity to reflect on the game’s strategy and analyze why and how it works. This taps into their metacognition skills, allowing students to understand their own thought processes and apply them to real-world scenarios.

Similarly, in math class, students learn that there are multiple ways to solve the same problem. A math teacher at Benchmark may present students with a division problem, and subsequently show four different ways of solving that problem. So, rather than focusing on the answer or memorization of the problem, the teacher is putting the emphasis on understanding the concept itself. This is the goal of most educators: to leave students more prepared to think for themselves and succeed in the world after their class, and Benchmark has built their learning process around that goal.

Ultimately, when deciding on whether or not your child is in the right environment, a parent’s gut instinct is valuable, Wonderland says. “If you feel like your school is not the right place for your child, you’re probably right.”

To learn more about alternative learning models and Benchmark School, visit benchmarkschool.org.

This is a paid partnership between Benchmark School and Philadelphia Magazine