Philly Doctors Discover Many Kidney Cancers Are Higher Risk Than Previously Known. Now They’re Using That Knowledge to Improve Care.

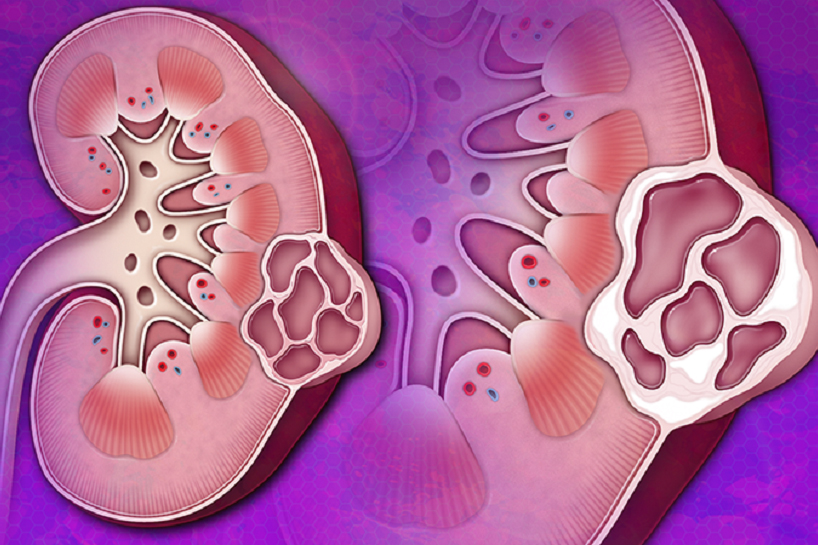

This side view of the left kidney shows a lump filled with fluid. Inside are thin walls or dividers, suggesting it’s cancerous—especially if they look thicker like the ones in the right picture.

Every cancer diagnosis comes with different levels of certainty, sometimes making a diagnosis tricky. The initial image offered by radiologic scans may look different once a cystic tumor is removed and examined by pathology. In other words, a cystic abnormality that looks like a low-risk cancer from the outside looking in–as captured by the scans–can be revealed to carry more risk when the physician looks directly at the tissue under the microscope.

The tricky part is when the tissue is in a difficult-to-navigate area and thus would require a significant surgical procedure to remove it. And it becomes a particularly difficult question when that area, such as the kidney, is prone to cysts.

“That’s the case with kidney cancer, where finding a cyst in people over age 50 is as common as finding a gray hair,” according to Alexander Kutikov, MD, FACS, Chair and Professor, Department of Urology at Fox Chase Cancer Center and one of the leaders of the Fox Chase-Temple Urologic Institute.

Nearly 50 percent of individuals in this age group will have cysts on their kidneys, and 80,000 people in the U.S. are diagnosed with renal cancers yearly. As a result, more and more physicians take a watch-and-wait approach called active surveillance, using scans to keep an eye on suspicious tissue instead of removing it. It’s been shown to be highly effective and has expanded to cover more and more types of tissue in the kidneys.

However, Kutikov and his colleague at Fox Chase-Temple Urologic Institute, Randall Lee, MD, Assistant Professor, Department of Urology at Fox Chase Cancer Center and Fox Chase-Temple Urologic Institute provider, recently published a paper that showed that when surgically removed and examined, many of the kidney tissues deemed safe by scans were, in reality, high risk–a surprising, even shocking discovery that cuts against the growing, standard approach to kidney cancers. And, while Kutikov and Lee caution that active surveillance remains a tried-and-true approach to kidney cancer, as kidney cancer rates rise, their report carries transformative implications for the future of detection, monitoring, and treatment of kidney cancer.

Alexander Kutikov, MD, FACS, Chair and Professor, Department of Urology at Fox Chase Cancer Center and one of the leaders of the Fox Chase-Temple Urologic Institute; Randall Lee, MD, Assistant Professor, Department of Urology at Fox Chase Cancer Center

How High Risk Cysts Went Undetected

For Kutikov and Lee, the idea that then-current medical literature around cystic renal masses might be misguided started as a hypothesis. And because Fox Chase holds one of the largest kidney databases in the country, it was one that he and his peers could test.

Reports and medical literature had been emerging suggesting that operating on cystic renal masses might not be worth it. These papers said that because cystic kidney masses cause little to no negative impact on patients’ lives or outcomes and that, subjecting patients to surgery, which always carries a risk of complications, is an unnecessary burden.

“What we wanted to see if those results correlated with what we see at our cancer center,” says Lee. Kutikov and Lee knew that the diagnostic determination given to renal masses could, and often did, change throughout treatment, especially in the final stage of pathology when a new clarity is offered. However, Kutikov and Lee noted a disconnect–pathologists and radiologists often operated on different ideas of what should be deemed “cystic”. As a result, tissue initially called cystic by a radiologist, and later found to be high risk by a pathologist was getting lost in translation, making cysts seem safer than they actually are. By examining the reporting around initial radiology reports and the final diagnosis from pathology further, Lee and Kutikov discovered an alarming discrepancy––about 23 percent of masses called cystic by radiologists were deemed a type of high-risk tissue by pathologists.

The Implications

The great news was that these risky cysts had been resected, but the bad news was that the danger these patients had been in was invisible. For doctors at Fox Chase, that lack of specificity and the potential it brought for patients’ risks to go unseen were unacceptable.

“It was an important finding,” said Dr. Kutikov. “There really are these sharks among the minnows that we need to identify and be able to detect better.”

By putting these findings down on paper, doctors Kutikov and Lee and their team hoped to change the conversations other urology doctors and healthcare teams were having. Cystic renal masses might be relatively safe, but the difference between a safe renal mass and a dangerous one can be difficult to spot—the sharks lurking among the minnows.

Still, it’s important to remember that active surveillance was shown to be a successful approach.

“What we don’t want is that our results flip the pendulum too far in one direction—that every single one of these masses requires surgery is not what we’re saying,” explains Lee.

Though under-treating a renal mass is a threat, there is also a risk of over-treatment. Calibrating treatment intensity to the needs of individual patients is key to optimizing outcomes; some patients may not be able to withstand potential complications from surgery, so the choice not to operate is the safer, better one.

“There’s an intricate balance,” Kutikov says about choosing a treatment plan. “You don’t want to suddenly manage all masses aggressively across the board.”

But that doesn’t mean there aren’t things to improve. Here is one thing the authors do want clinicians to do: apply a careful and critical eye to the information they read and use to educate patients. Examining how authors collected and sourced their data is just as, if not more, important to reading results—just think about how the gap between radiology and pathology would only have widened had Fox Chase not looked at the data for themselves.

As increased data becomes available, radiology also stands to improve through better data usage–so that cancer can be detected at the outset, when a treatment plan can still be developed, rather than having to wait until resection to understand risk fully. It’s with these challenges that artificial intelligence can help accurately diagnose patients.

“It’s starting to become exciting with the implications of AI to advance the quality of the images,” says Lee. With AI scanning their radiographic images, patients may get insights into their future—based on pathologic data—before surgery. It can help fast-track them into an operation or help them avoid an unnecessary procedure.

So, while the findings may seem to push against the reduction of surgery in kidney cancers, in reality, Kutikov and Lee are looking to refine their approach and tools further to risk stratification in kidney cancer–to keep patients as safe as possible with as little treatment as possible.

“We see a lot of patients,” Kutikov says. “But there are things that happen in front of us every day that need to be identified, and Fox Chase has the ability to push pause and answer some critical questions that will change how people are treated. That really excites me about my work.”

This is a paid partnership between Fox Chase Cancer Center and Philadelphia Magazine