Heart Failure Is on the Rise. These Philly Physicians Developed a Way to Save More Lives with Heart Transplants

There are few surgeries that carry more weight than a heart transplant. It’s an amazing, dramatic technical feat–the fact that we’re able to replace what we’ve always thought of as the core of our bodies–and more importantly, it’s a surgery that regularly saves lives. Unfortunately, however, the number of people requiring this life-saving surgery is increasing.

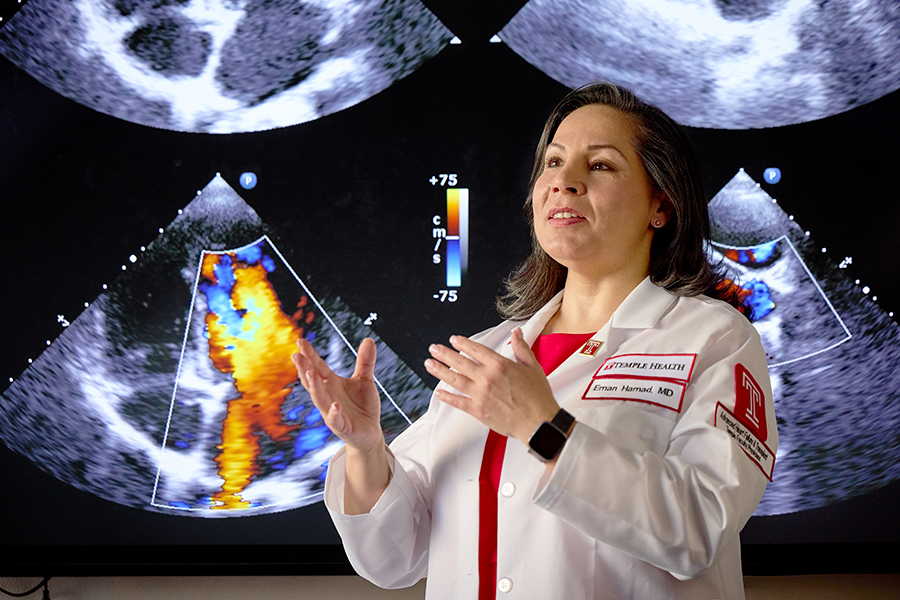

“The data has shown that patients with advanced heart failure–and those are the patients we evaluate for transplants and heart pumps–have a mortality rate of 50 percent after one year,” says Dr. Eman Hamad, heart failure and transplant cardiologist at Temple Health. “Currently we have about 6 million people facing advanced heart failure. It’s expected to grow up to 10 million in the next ten years. So the numbers are rising exponentially.”

While there is a critical need for transplants, the criteria to qualify can be limiting. Most centers have tight parameters for age, weight, and preconditions that can disqualify patients who are otherwise largely healthy. As the number of heart failure cases increase, those limitations will cause more and more people to be left in need.

There’s a light of hope in Philadelphia, however–one that is already having an impact nationally. At the Temple Advanced Heart Failure, Transplant, and Mechanical Circulatory Support Program, the team has developed expanded criteria for more patients to qualify for transplant, while also reducing the time it takes to receive a transplant. These new standards have drawn patients to the program from across the country who were previously denied this life-saving treatment.

“These set guidelines are international, and only a limited number of centers even try to expand,” Hamad says. “As a result, about 50 percent of our patients were rejected from other centers.”

To find out how the program has managed to give hope to those without, we asked Hamad, who directs the Temple Health program, how she found a way to help these patients.

Nikky C. (right) with Patrice M. Schneider CRNP, CHFN, Mechanical Circulatory Support Coordinator. The two have become good friends during Nichole’s journey to qualify for a heart transplant.

Expanding Opportunities

According to Hamad, it starts with the fact that many patients that are treatable are turned away. The list of health factors that can disqualify you from a heart transplant by a standard center is long: a history of cancer, hepatitis C, HIV, or previous treatments like radiation or sternotomies; patients over the age of 70 or who are obese; Jehovah’s witnesses who require surgery that fits within religious requirements–the list goes on. When Hamad considered these patients, she thought to herself, who can they turn to?

Hamad came to Temple with the idea of finding a way to treat these patients, rather than turning them away before a complete evaluation. As a start, Hamad noted that patients who were otherwise healthy were getting refused a transplant simply because of a check in a box.

“You might have a patient who is over the age of 70, for example, that’s being turned away, who on every other factor is healthier than a younger person who receives the transplant,” Hamad says.

So, she began evaluating each person beyond the given standards. Hamad created a screening checklist and started looking at each critical system in her patients’ bodies with an interdisciplinary team.

“We draw from departments across the health system, and on every organ function, whether it’s pulmonary or liver or kidney, they do an assessment and give us their input,” Hamad says. “For instance, if somebody has a history of cancer, we make sure that we have at least two opinions from oncologists on how their health would be long term with a heart transplant.”

For patients who proved healthy outside of a minor factor like age, she offered to help them without further delay. But the critical innovation came with the fact that, when Hamad and her team did discover an underlying health condition, they leveraged an interdisciplinary team to help prepare a patient to qualify for heart transplant, if at all possible.

For patients at higher risk due to prior cardiac surgeries, radiation or any organ dysfunction, for example, the team creates a treatment plan to optimize their heart function prior to surgery to reduce risk. Sometimes this includes a temporary heart pump that can give them support until a heart transplant is possible.

And the benefits of the evaluations themselves go beyond heart transplants. When the patient is ruled inappropriate for a transplant, the evaluative process gives Hamad the capability to treat their conditions, when possible, with a long-term implantable heart pump, or Left Ventricular Assist Device (LVAD). Those are benefits patients would never have received if they were simply turned away.

Taking that analytical and equitable mindset to heart transplants has even helped Hamad and her team speed up the time to transplants–they also analyze individual donor hearts for their efficacy based on clinical data, rather than ruling them out because they were rejected by other centers, or don’t fit within a specific guideline, which has allowed her to increase availability.

Standardizing the Second Chance

It’s that expansive vision that has made her approach transformative–because Hamad isn’t simply performing evaluations on a case-by-case basis. Each time a patient with a new set of conditions comes to the center and is treated, Hamad and her team review how the process went. The team then uses the results of that review to craft protocols on how to approach particular types of patients.

“By doing these nontraditional cases, our surgeons develop techniques to optimize these patients. And then they’re prepared for similar patients in the future,” Hamad says. “We consistently adapt the protocol for the best outcomes.”

These protocols are also multidisciplinary and can involve staff throughout the health system. Since lack of follow-up care can be a risk factor, even patients who lack social support are accounted for–social workers in the hospital work with patients to ensure that they can find the means to get to the program over time.

“As opposed to telling them they’re not a candidate, we find a way to get them there. For patients who can’t read or write, we figure out ways to make sure they can take their medications on a schedule. We work with the patient to make them good candidates,” Hamad says.

Rohit Soans, MD, medical director of the bariatric surgery program at Temple Health, works in tandem with the advanced heart failure team to help patients reach their healthiest weight in support of their heart and overall health.

Putting It into Practice

All those factors, when brought together, have saved patients like Nikky C., a young, single mother who came into the ER with a cough, and then was told she had heart failure.

“I found out I was between life and death; any minute I could die,” Nikky says. “My daughter was two years old when I found out, so I was scared for her.” She was given a left ventricular assist device (or LVAD), to help her heart function.

Dr. Rohit Soans, medical director of bariatric surgery at Temple Health, notes that patients like Nikky can get trapped in a difficult situation. Nikky, struggling with obesity, didn’t qualify for a heart transplant. But as long as she had heart failure, she was not a traditional candidate for bariatric surgery either, a surgery that patients in Nikky’s condition often require to achieve permanent weight loss. Because they don’t qualify for either surgery, they’re stuck requiring the support of the LVAD, which makes life difficult. Nikky has to wear battery packs that support the device, and she has to limit exposure to water.

“It puts these patients in a precarious situation, where they’re in limbo,” Soans says. “It’s not a lifetime fix–LVADs have limited shelf lives–and these patients have to deal with complications and a lot more maintenance for the LVAD than if they had a heart transplant.”

After receiving her LVAD, Nikky was referred by Hamad and her team to Soans for evaluation, with the goal of preparing her for transplant. Hamad and Soans had previously begun working together through an advanced heart failure and bariatric collaborative, but Nikky would be the bariatric team’s first LVAD patient. The collaborative was so moved by Nikky’s story and her concern about her daughter’s future, they started discussing ways to best optimize her health while she was still dependent on the heart pump.

“Everyone was super motivated and agreed we had to help her,” Soans says. Fortunately, Nikky was motivated as well. With help from her bariatric team, who did everything from scheduling appointments to ordering meals, she got her weight down to 160 pounds, from a high of around 300, through lifestyle changes alone in order to qualify herself for bariatric surgery. As Soans notes, these lifestyle changes are necessary in order to demonstrate that the patient will be able to keep the weight off after surgery, but the surgery itself is still critical: Exercise can be extremely difficult for heart failure patients, so the weight is easy to put back on without surgical assistance, especially for patients whose bodies have a natural tendency toward obesity.

Soans and Hamad’s team then optimized her cardiac function as best they could, and Nikky received successful bariatric surgery. She is now in the final phases of qualifying for a heart transplant.

“I’m looking forward to going swimming and taking full showers. They told me I could even ride all of the rollercoasters in Disney World, so I’m going to head there first,” Nikky says. “The main thing is being able to live for my child and make sure she’s OK.”

Measuring the Impact

Nikky’s journey won’t only help her and her family. Thanks to the multidisciplinary team that Hamad and Soans put together, a standard protocol was created based on Nikky’s improvement, and is now being applied to a different patient’s case, with two more patients under consideration.

“The kind of weight loss that patients like Nikky needed, the rate of people able to lose the weight is less than 1 percent,” Soans says. “But now I tell my patients that, if we were able to help Nikky–a patient who is on an anticoagulant, has an LVAD, and heart failure–then we’ll be able to help you.”

For Hamad as well, her innovative approach to crafting protocols has allowed her team to build up an extensive body of knowledge that makes them the place for not only second chances in the nation but for expertise in heart transplants in general. And in 2019, Hamad formally expanded the program’s official heart transplant criteria, signaling to other health systems that more is possible.

Hamad estimates that just 10 percent of patients who could benefit from transplants and LVADs nationally actually end up receiving them. “It is a point of pride for us that we do help those who no one else was willing or able to help. And through this work, we are able to make a difference in the field.”

This is a paid partnership between Temple Health and Philadelphia Magazine