This Philly “Super-Team” Is Working To Decode One of the Most Mysterious, Dangerous Cancers

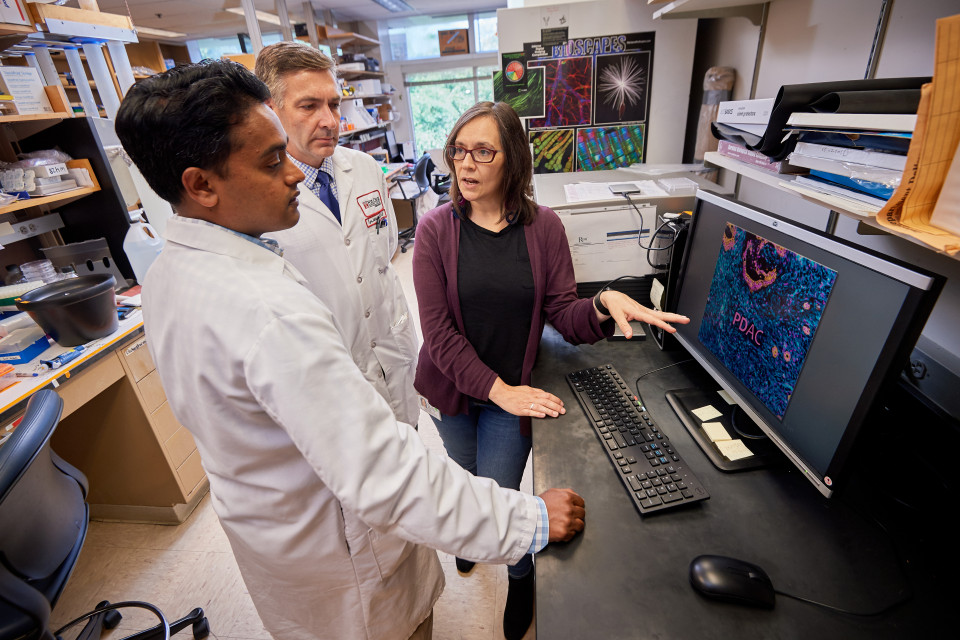

(From left) Dr. Sanjay Reddy, Dr. Igor Astsaturov and Dr. Edna Cukierman, co-directors of the Marvin and Concetta Greenberg Pancreatic Cancer Institute at Fox Chase Cancer Center, discuss pancreatic tumor biology.

Our best shot at neutralizing cancer is not necessarily a cure. Cancer is a vast, complex disease, and the battle between the body and the cancerous cells can be unpredictable. Cancer lesions are often invisible to the naked eye, resilient and difficult to eliminate, each one containing its own little unpredictable quirks. Quirks that, while literally microscopic, nevertheless determine the difference between success and failure.

But that’s not being pessimistic. The scientific community is making incremental improvements day by day. Long before we discover a cure that wipes the disease out, we may find it has a reduced presence in our lives, thanks to those incremental efforts that limit the pervasiveness and deadliness of the disease.

“We have all realized that when treating cancer, there’s not one magic bullet. Success is a culmination of the group’s efforts,” says Dr. Sanjay S. Reddy, a surgical oncologist at Fox Chase Cancer Center and Co-Director of the Marvin and Concetta Greenberg Pancreatic Cancer Institute. “As therapies get better, as our technologies advance, as delivery of treatment becomes more precise…patients will do better, they’ll live longer, and we’ll keep learning in the process.”

That’s not to say that all progress is a matter of baby steps. In Philly, the effort may have taken a leap—not just through a single discovery, but through an innovation in process.

Fox Chase Cancer Center has assembled a team of researchers, oncologists and surgeons who collaborate in a massive effort against perhaps the most difficult to understand type of cancer, and one of the deadliest—pancreatic cancer. In 2017, they launched the Marvin and Concetta Greenberg Pancreatic Cancer Institute to capitalize on their innovation and expertise in not only the clinical aspect of pancreatic cancer, but also the basic science of the disease.

Through a combination of real-time treatment and new breakthrough clinical trials, they’re steadily working on cracking the code of a cancer that, perhaps more than any other disease, approaches indecipherability. In the process, they’re creating a model of how to change the nature of cancer care the world over.

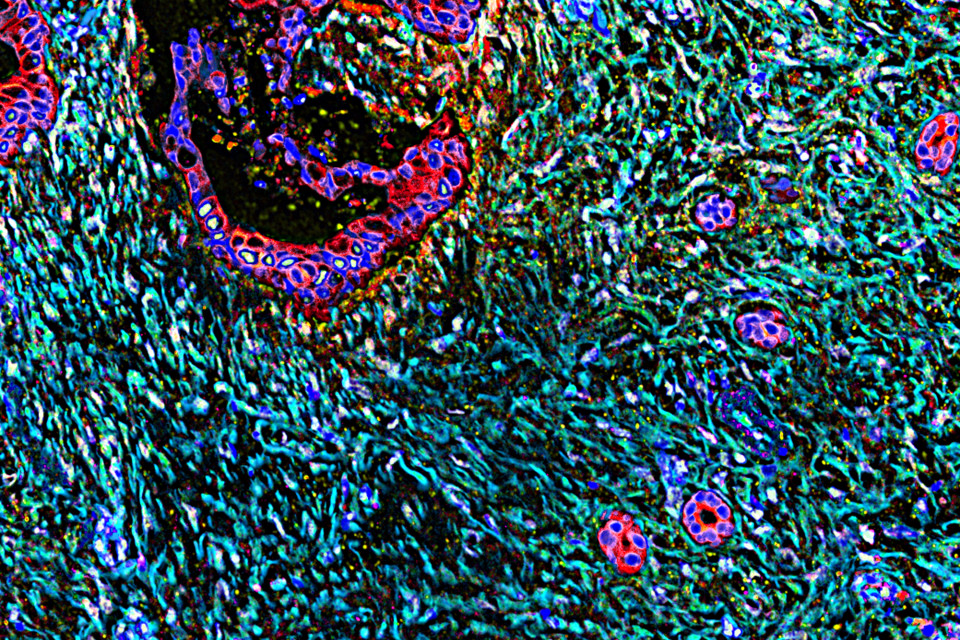

A human pancreatic tumor mass, showing a vast stromal expansion. Credit: Dr. Edna Cukierman and Neelima Shah.

A Difficult to Detect Disease

Pancreatic cancer does not have the infamy of breast cancer, for example, or prostate cancer. But for those diagnosed, it’s one of the most terrifying. It has a 10% survival rate.

Like many cancers, it’s not a matter of one, single problem to overcome. The challenges to reaching remission are manifold.

The problem starts from the outset, with diagnosis. For the majority of patients, diagnosis comes late, past the point of surgery or survivability because the tumor does not initially cause pain or symptoms in a clear way.

“The majority of patients will present with disease that is already locally advanced, or has already spread,” Reddy says. “Diagnosis at an early stage is difficult.”

That proved true for Andre Burke, an AMTRAK conductor living in Philly. Burke’s father lost his life to pancreatic cancer, something that has worried him throughout his life. And yet, because pancreatic cancer’s symptoms are often different from patient to patient—and most often, they don’t present at all—it was difficult for Burke to recognize the threat prior to his diagnosis.

While he did receive a minor indication, experiencing small abdominal pains, at 315 pounds and accustomed to eating on the go, he assumed they were just a result of poor diet.

“It wasn’t a bad pain. It was tolerable. And that’s actually worse because if it’s tolerable eventually you’ll forget about it,” Burke says.

Then he started losing weight, about 7 to 10 pounds a week. While he wasn’t upset at the loss, after speaking with his wife about the ongoing abdominal pain and the weight loss, she convinced him to visit the hospital. He received a biopsy, and finally the diagnosis came—pancreatic cancer.

“The first thing I thought was, ’Am I going to see my kids grow up? Am I going to be here for my wife?’” he says. “It was the same thing my dad went through.”

Fortunately, after some deliberation, he chose Dr. Reddy and his team. Fox Chase has long practiced a research-backed approach to treating pancreatic cancer called neoadjuvant therapy—a method of delivering therapy prior to surgery, with the attempt of shrinking the tumor and treating microscopic lesions that are not otherwise visible.

“We were first recommended to Fox Chase, and Dr. Reddy really related to me,” Burke says. “He explained to me that they were going to shrink the tumor before surgery. The phrase that captivated me was ‘We can treat you.’”

To live up to that promise, Reddy would bring to bear the full extent of his team’s ability to treat this most enigmatic disease.

The Body’s Battle

This is where the mystery of pancreatic cancer takes on real-world relevance.

Pancreatic cancer is unique in the body’s response to it. When the body grows a tumor in the pancreas, it is often accompanied by the development of a kind of fibrous, layered tissue among various non-cancerous cells, which altogether is known as stroma. This tissue attempts to battle the tumor, surrounding it and sometimes physically limiting its growth while simultaneously releasing chemicals that fight but also, in a complex, adverse reaction, often protect its growth.

This evolutionary defense also comes at a cost. The growth of the stroma in the pancreas can choke off vital organs, essentially doing the tumor’s fatal work for it. Given the lack of symptoms, by the time pancreatic cancer is detected, the stroma-tumor complex is usually so well-developed, it can’t be removed without potentially damaging critical organs, or even more dangerously, leaving behind fragments of the tumor that can then grow back.

“It’s counterintuitive because if you get rid of the stroma, the tumor can grow even faster, so you can’t just get rid of it,” says Edna Cukierman, PhD., Co-Director of the Marvin and Concetta Greenberg Pancreatic Cancer Institute and a basic scientist on the team with Reddy and numerous others who specialize in unlocking the stroma.

The team effort is crucial in the care of pancreatic cancer patients.

Honing Patient Treatment

This is where Dr. Cukierman’s work—and in fact, the whole Fox Chase team—comes into play. One important key to a successful treatment for pancreatic cancer is to shrink the stroma-tumor complex prior to removal, so that no organ is harmed during surgery and the whole tumor can be taken out at once, preventing any rapid regrowth. That’s what neoadjuvant therapy is all about.

“The way I came to understand it was, if you put a cotton ball (the tumor) on a piece of Velcro (surrounding tissue), you can pull it off, but some of the cotton will still be on the Velcro,” Burke says. “The neoadjuvant radiation and chemotherapy treatment makes the tumor shrink in the hope that vital organs are not damaged during surgery and no cancer cells are left behind.”

The stroma is incredibly sensitive. If the wrong therapeutic approach (that is, the wrong combination of chemotherapy and radiation) is applied, the stroma can refuse to shrink, or even heel-turn from ally to villain—If the wrong chemical environment is created, the stroma can actually flip and accelerate tumor development.

This is why Fox Chase has assembled their super-team of oncologists, basic research scientists, geneticists and even sociologists. What determines why the stroma behaves the way it does, whether refusing to shrink or changing its attitude and siding with the tumor, appears to be down to a nearly unpredictable Rubik’s cube of factors—nearly. The team has seen positive responses change based on stage of the cancer, genetics, even the environment where the patient grew up in. With each case, it’s their mission to pin down the exact, life-saving combination of treatments.

Defeating What We Don’t Understand

Their approach combines real-time treatment with an eye toward long-term innovations, bringing a unique approach to each case that then provides new insight into the problem overall.

This benefits the patient’s experience. When a patient is diagnosed, they don’t merely see an oncologist or a surgeon. They have access to the full, aforementioned team of researchers as well, and the team discusses the case together.

The team’s influence on care extends beyond that however, both prior to and post care. For one, the team has created a new model of clinical trial design together, which provides patients access to care that’s advancing in real time according to the leading knowledge across fields. Surgeons and oncologists report on what they’re seeing in real-world patient cases, which researchers combine with trends they’re seeing in the lab to create each clinical trial. Results are stored for further examination—resulting in a model of continual improvement.

“I ask our scientists, why did this tumor react this way, and not that person’s tumor? What markers were present that led to this outcome? Every tumor that we remove, we try to bank and run different tests on so we can develop different models. We then use that information to move forward with other hypotheses,” Reddy says. “It’s like this jigsaw puzzle where you’re trying to put all these different pieces together to see what causes what. That’s where it becomes complex, and that’s where the team approach is critical.

Developing New Techniques

This both benefits patient care in the short term and improves the long-term fight against pancreatic cancer. An example has been the use of pulsed, low-dose radiation therapy to treat pancreatic cancer. Cukierman was learning about some laboratory research by colleagues studying another type of cancer when she noticed they mentioned a biomarker, a kind of controlled variable for the experiment, that stood out to her. When the collective team examined the data, they noticed that the controlled variable was actually producing a different effect on the stroma than other experiments—a significant reprogramming.

“That specific biomarker they were just using as indicative of changes, but to me it was indicative of reduced inflammation and fibrosis [rewiring of the stroma],” she says.

Cukierman immediately began working with Fox Chase radiation oncologist Joshua Meyer, MD, to develop a new clinical trial, based around time of exposure to therapy. It turns out, as preliminary results suggest, that the stroma and other tissue surrounding the cancer cells recover faster from damage than the cancer cells themselves. So, if you provide the patient with a faster but shorter series of doses, referred to as pulses, you can deliver the same amount of cancer-killing radiation with less damage to the healthy cells.

“If you just give cancer cells a little bit more damage than healthy cells, they die,” she says. “So because it is in pulses the healthy cells have time to recuperate, and suffer no permanent damage, which can eventually help to naturally eliminate the resilient cancer cells.”

Several years out, Andre Burke is doing well.

The Impact on Patients’ Lives

It is this kind of team approach that benefitted Burke. Through a collective effort, he saw minimal impact from therapy in the run up to surgery, and when surgery came, he didn’t feel afraid.

“Dr. Reddy was very confident, which gave me confidence,” he says.

According to Reddy, it wasn’t just about his surgical ability. The neoadjuvant therapy did its job.

“[Prior to surgery] his tumor went from the size of a grapefruit to a golf ball,” Reddy says. “He had an amazing response.”

The removal of the tumor was successful. Three years later, Burke is doing well—and that’s significant.

“He’s several years out now without evidence of recurrence. As patients approach five years, their outlook improves substantially,” Reddy says. “Ten years ago, without the therapies we have now, I don’t know if we would have had the same outcome.”

Building on Every Success

Burke was a success, and his success will not only be critical for his life and his family, but it will contribute to a growing body of research the Fox Chase team is compiling. If pancreatic cancer represents one of the most complex puzzles cancer has to offer, then the Fox Chase team has set about creating an ever-improving codex that their team and others can benefit from: a database that records the reactions of the stroma and cancer to particular treatments, according to variables ranging across every demographic, genetic history and beyond.

“We try to understand both the macro and micro-environment, from their genetic lineage to the quality of the water or the air in their neighborhood,” Dr. Cukierman says.

According to Dr. Cukierman, it’s a way of one day ensuring that cases like Burke become standard.

“Even though pancreatic cancer has a terrible prognosis,” she says. “We have doubled the survivorship in less than ten years. We want to continue that progress.”

This is a paid partnership between Fox Chase Cancer Center and Philadelphia Magazine