Why the Fields of Cardiology and Oncology Are Coming Together to Save Lives

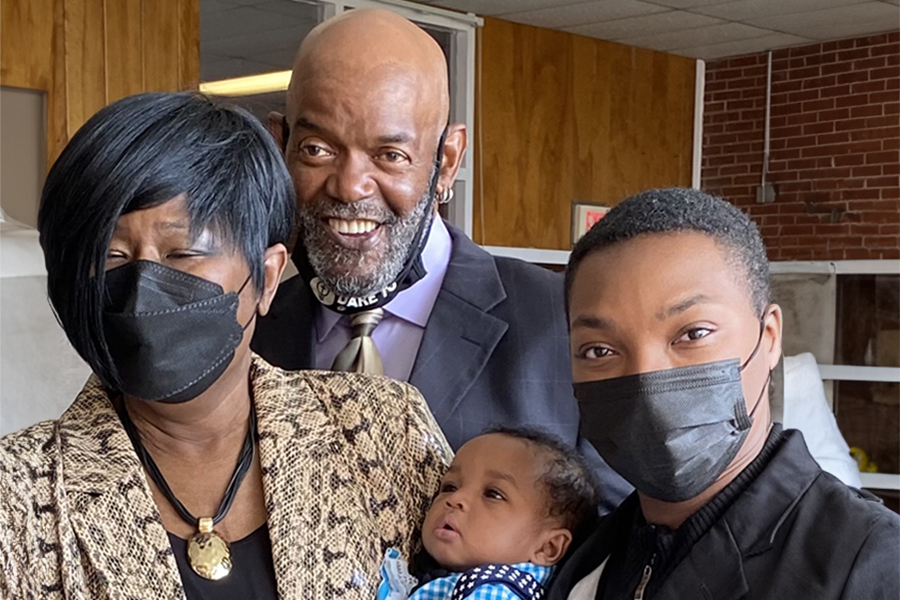

The last thing you want to hear when you’ve just survived a heart transplant is, “You have cancer.” But that’s the experience that Theresa Alexander, a heart health advocate, went through when, in 2019, about one year after she finally received a successful transplant to correct her heart failure, she was told she had cancer. Prior to that diagnosis, she had spent thirteen years struggling with her heart condition, going through multiple valve replacements while working as a paralegal and tending to her growing family (she’s now a grandmother with three grandchildren and a devoted husband who has been with her through each treatment, whom she calls her “rock”).

After all she went through, she was faced with the question of why would she have to go through these two major health crises so close together.

“Somebody would ask me, ‘Do you ever think about why you why you?’” Alexander says. “And I say ‘No, I believe it’s a test. This way I will be a testimony–this way I can tell my story.’”

But in addition to that question, she and her physicians had to face the immediate, practical question–would the heart she just received be able to stand the treatment?

“They did tell me that the radiation and the chemo would affect the heart, when I asked them if they were concerned about my heart,” Alexander says.

An Emerging Field

That question has become increasingly urgent for a growing number of people with a wide variety of cardiac conditions in recent years, and it’s given rise to the new field of cardio-oncology, a cross-disciplinary practice that brings together cardiology and oncology.

“Many cancers have become treatable,” says Rupal O’Quinn, director of cardio-oncology at Penn Medicine. The vastly complex challenge of cancer, while often not curable in advanced stages, can now be tackled with not only the classical methods of chemotherapy and surgery, but also managed with new, medical technologies like targeted therapy, which hones in on the tumor, and immunotherapy, which helps the body’s own immune system battle cancer, increasing longevity even when a cure isn’t possible.

However, the development of these new treatment methods, and the fact that cancer is increasingly considered a chronic condition that needs long term treatment, means that long term exposure to these treatments need to be accounted for. At the heart of that question of long term health is, of course, the heart–in part because deaths due to heart conditions are the leading cause of death outside of cancer, and cancer treatment puts additional stress on the body. But even more to the point, new therapies, while easier on the body overall than chemotherapy, can, in dismantling cancerous tissue, attack vulnerable healthy blood vessels as well.

“The top two causes of death in the United States are cancer and heart disease,” O’Quinn says. “All of these different types of therapies target different cancers and different aspects of the cancer. And some them also affect the heart and cardiovascular system.“

That’s the origin of cardio-oncology, which seeks to tackle two of the most pressing causes of death in patients. O’Quinn was an early expert in the field, which took off as the use of targeted therapies accelerated in the past two decades. She now helps patients who are at risk of cardiovascular health issues during and after treatment. That includes patients who have prior heart conditions going into treatment, patients who require cancer treatment that may particularly impact the cardiovascular system, and patients who received treatment in the past that puts them at risk today.

The approach does not usually have to involve a surfeit of advanced medicines: getting patients in improved cardiovascular shape through lifestyle changes, carefully monitoring their cardiovascular performance for indicators of increased risk during treatment, and making sure they’re taking the best medications to ward off potential issues, even treatments as simple as consistently taking aspirin.

Supporting the Patient

One of O’Quinn’s priorities is to make sure that process of treating the heart does not require interfering with cancer treatment. In fact, the role of a cardio-oncologist can often act as a bridge between the increasingly specialized disciplines of oncology and cardiology, helping each department feel confident that their approach is safe. For a patient like Alexander, that kind of collaboration gives them security in their treatment–though she did not work with O’Quinn, she had direct experience of her doctors as cooperative decision-makers.

“Because my heart doctor was working with my oncologist, it was perfect. Because I knew she was monitoring everything. And we had a rapport,” Alexander says. “They were always talking with each other.”

Now cancer-free and retired, she spends her days helping care for her grandchildren, seeking to give back for the help she received. And she exercises regularly–because her heart is still strong.

This is a paid partnership between Go Red For Women and Philadelphia Magazine