This Genetic Mutation Raises Your Cancer Risk. Here’s Why Philly Researchers Think They Could Find a Fix in Broccoli

(Left) Joseph R. Testa, PhD, FACMG, Chief of Genomic Medicine – Fox Chase Cancer Center; (Right) Joseph Friedberg, MD, FACS, Thoracic Surgeon-in-Chief – Temple Health System, Co-Director of the Temple-Fox Chase Cancer Center Mesothelioma and Pleural Disease Program

For someone with a family history of cancer, the fear of being diagnosed with cancer themselves can be lifelong. But as our understanding of the role environment and genetics play in developing cancer has improved, and our ability to predict the risk of cancer has grown, patients and their physicians are increasingly seeking out ways to get proactive about their risk. That’s led to a growing focus on prevention and interception in cancer treatment–the idea that cancer can be stopped before it even begins to develop.

“The idea is to get somebody the benefit [of prevention] before tumor formation,” says Dr. Joseph Testa, Chief of Genomic Medicine at Fox Chase Cancer Center in Philadelphia. “It’s better not to get mesothelioma or other cancers than to try to treat them.” As an expert in gene-environment interactions, Testa studies how a person’s behavior within their environment can bring out genetic tendencies that drive cancers–and through preventive measures that address those interactions, potentially prevent cancers from developing in the first place. This approach has made Testa a world-renowned authority in the molecular biology of mesothelioma, a cancer with no known cure, and led to his groundbreaking discovery of the BAP1 gene mutation’s role in making certain families highly susceptible to a number of cancers including mesothelioma, now known as the BAP1 tumor predisposition syndrome.

Now, Testa has brought that expertise to a partnership with Dr. Joseph Friedberg, Thoracic Surgeon-in-Chief for the Temple Health System, and Co-Director of the Temple-Fox Chase Cancer Center Mesothelioma and Pleural Disease Program, one of the most comprehensive mesothelioma programs in the United States. Friedberg has operated on hundreds of patients with mesothelioma and has helped manage the treatment of many more. He is one of the pioneers in lung-sparing surgical techniques for mesothelioma and, as an internationally recognized expert in the treatment of mesothelioma patients, perfectly complements Testa’s scientific expertise, bringing extra gravitas to their partnership.

After years of both experts admiring each other’s work, the two are combining their boots-on-the-ground clinical experience and scientific curiosity to study an early idea of Friedberg’s–a potentially transformative preventative treatment for mesothelioma and possibly other cancers that could give hope to at-risk patients. And surprisingly enough, that breakthrough treatment involves a compound found in broccoli (as well as other cruciferous vegetables.)

“When your mom told you to eat your vegetables, that was actually really good advice,” Friedberg says. The compound, called sulforaphane, is currently being studied by Friedberg and Testa under a three-year, $1.2 million contract from the National Cancer Institute as a potential way to prevent mesothelioma. And if the findings are particularly promising, the compound could have implications for a wide variety of the increasing number of cancers linked to genetics.

The Underlying Causes of Cancer

Friedberg and Testa had each been working on treatments or potential preventive strategies, respectively, for mesothelioma for years before being able to combine their expertise at Fox Chase Cancer Center. As an innovative thoracic surgeon, Friedberg had seen firsthand the suffering that mesothelioma causes, developing multiple groundbreaking and demanding surgical techniques to improve the quality of life in these patients.

“It’s a deadly cancer,” Friedberg says. “There isn’t a method of prevention.”

And as a child of a working-class background with family members who worked with asbestos, Testa had an interest in mesothelioma from early on in his career. Both, Testa through his upbringing, and Friedberg through his patients, were highly motivated to find ways to not only treat, but prevent, the development of mesothelioma.

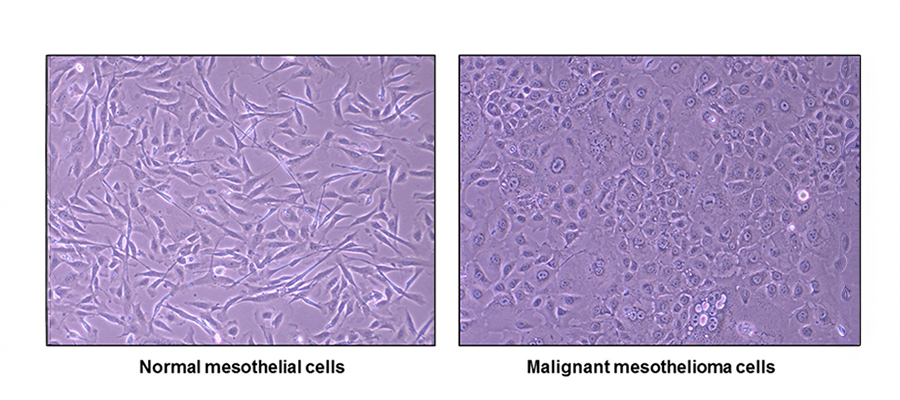

The image on the left shows normal mesothelial cells which are relatively uniform and spindly. If they become malignant, as shown on the right, the cells take on very disorderly shapes.

That effort took a large step forward thanks to the revolutionary discovery of the BAP1 syndrome by Testa and colleagues. To prevent cancer effectively, you need to be able to identify who will be at risk of cancer in the future–and that can take some creative pattern recognition. While most mesothelioma cases occur in isolation in a family, others have been found in clusters, suggesting that the latter might be driven by a genetic mutation. After using a certain technique to examine the entire genome of a single mesothelioma from each of two American families who had a history of this disease, a genetic commonality was observed, and DNA sequencing of the gene located at this common site led to a breakthrough.

“One family we looked at had seven cases of mesothelioma and the second had five mesotheliomas,” Testa says, noting that patterns could be seen for generations. It turned out that these families also had several other tumor types such as uveal melanomas (a type of eye cancer), skin cancers, kidney, and other carcinomas, and we suggested that inherited mutations of the BAP1 gene are associated with a hereditary disorder, which would later be recognized as the BAP1 syndrome. The BAP1 gene is a tumor suppressor gene, which normally enables the body to suppress tumors, but an inherited mutation of this gene puts affected families at very high risk of certain types of cancer.

“The most common of these are uveal melanoma and mesothelioma. But you can also have kidney cancers, basal cell carcinoma, melanomas, and brain tumors known as meningiomas” Testa says. Since then, dozens of families have been identified with this condition. In looking at the data, Testa came to understand that certain behavioral factors, in combination with the BAP1 mutation, can cause the development of particular cancers, from asbestos exposure causing mesothelioma to arc welding driving uveal melanoma to sun exposure being linked to melanoma.

A series of guidelines now exist for behavioral modifications for people with BAP1 syndrome–avoid overexposure to sun and environments with asbestos, and have regular eye exams, ultrasounds for abdominal mesothelioma or kidney cancer, and dermatological exams for potentially cancerous tissue. But Testa was always on the lookout for a more proactive measure–one that he found when he began to work with Friedberg.

Eat Your Vegetables

While Testa’s discovery helped advance the field’s understanding of who would develop mesothelioma, a proactive treatment had yet to be discovered–and that’s where Friedberg’s innovations in sulforaphane came in.

Friedberg was inspired to look for a preventative compound for mesothelioma by an experience he had early in his career. He had met a patient in her 40s with mesothelioma, who had another sister around her age.

“Two sisters show up. Their dad worked at the shipyard, and they used to wash his clothes, and one of them has mesothelioma, and the other one doesn’t but says, ‘What about me?’” Friedberg explains that because of their shared behavior and shared genetics, that meant the other sister was at risk of developing mesothelioma as well. “‘What do I do?’ Kind of waiting for the other shoe to drop. And as of now, kind of the best we have is, ‘I guess we could scan you and we’ll keep an eye on you and hopefully, you won’t develop mesothelioma.’”

Friedberg was frustrated by what he could tell her –he wanted to offer the cancer-free sister greater hope for her future, something she could actually do to prevent the cancer. Since mesothelioma typically develops several decades after asbestos exposure, he needed something that she, and patients like her, could take for decades–something inexpensive, natural, non-toxic, and with low risk of side effects from long-term exposure. And because mesothelioma associated with BAP1 syndrome is caused by a mutation in a tumor suppressor gene, it would have to aid the body in the work of suppressing the development of cancer.

Could broccoli be a new miracle drug?

After some research, he learned that sulforaphane, a compound in cruciferous vegetables like Brussels sprouts and broccoli, might be what he was looking for. The compound has what Testa calls epigenetic effects–it affects the way your genes behave.

“What this drug is supposed to do is have certain epigenetic effects,” Testa says. “That means it has some effects on the expression of specific genes that appear to be involved with cell survival and cell proliferation,” helping the chemical processes that regulate DNA and keep it functioning correctly. That process, operating on a daily, incremental level, may help prevent the development of mesothelioma after asbestos exposure.

Friedberg did some preliminary work with a scientist at his prior institution in Maryland, and the results for sulforaphane and mesothelioma cells in a dish were encouraging. Once Friedberg came to Fox Chase, he immediately sought out Testa to discuss this idea. Through Testa’s world-class experience with models that simulate mesothelioma in humans, he and Friedberg are going to be able to test the theory in Testa’s lab at Fox Chase. That’s what they’re currently researching through a recently launched study funded by the National Cancer Institute on the use of sulforaphane to prevent mesothelioma.

“What we’re hoping is that if we give them sulforaphane, that will be able to prevent mesothelioma,” Friedberg says.

The implications of the study do not stop at mesothelioma, however. According to Testa, a result that shows sulforaphane is effective would be significant enough for Testa and Friedberg to explore its application for other cancers caused by BAP1 syndrome or for anyone at risk, especially those with asbestos exposure. Testa believes that the results could have implications for other cancers driven by gene-environment interactions.

“Whatever we learn about sulforaphane preventing asbestos-induced mesothelioma may be applicable for cancers caused by cigarette smoke, or other diseases caused by other carcinogenic agents,” Testa says. “So many agents, unfortunately, that we are exposed to are turning out to be carcinogenic; what we learn here can have broad-ranging implications.”

In the meantime, Friedberg is taking the complex himself (he had an asbestos exposure early in life.) But most importantly, Friedberg may soon be able to talk to patients with confidence about the solution that he wanted to be able to offer patients years ago.

“My hope is that when I see two sisters again,” Friedberg says, “and one of them has developed mesothelioma, and the other asks, ‘What about me?’ that I’ll be able to tell her, ‘We found something safe and cheap that you should take and it will prevent you from getting this cancer.’”

This is a paid partnership between Fox Chase Cancer Center and Philadelphia Magazine