With 15 Million U.S. Adults at Risk for Alzheimer’s, Philly Scientists Are on the Case

Alzheimer’s disease already affects approximately 6 million Americans. But as people live longer and doctors develop more efficient diagnostic tests, that number could potentially more than double, experts predict. Scientists across the country are working harder than ever to learn more about this debilitating disease and research new treatments—especially at a hub right here in Philadelphia.

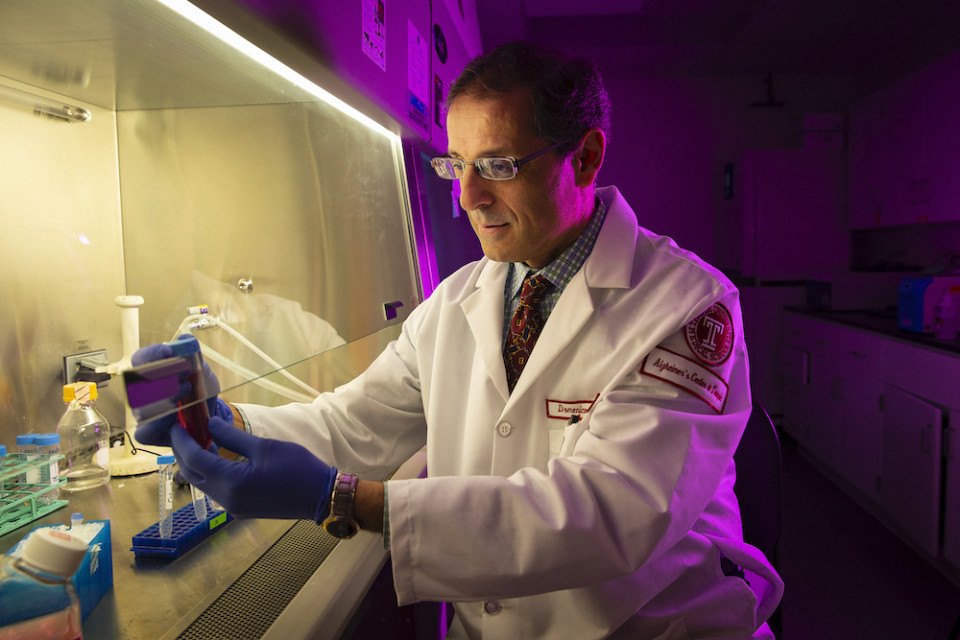

Led by Domenico Praticò, MD, the Alzheimer’s Center at Temple (ACT) aims to create better outcomes for every person affected by this illness. “About every 70 seconds, someone receives a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease in this country,” Dr. Praticò says. “It’s a disease where the toll we pay is not just the patient, but also the caregivers and family involved.”

Alzheimer’s disease accounts for up to 80% of dementia cases and causes progressive memory loss and other cognitive changes disruptive to daily life, according to the Alzheimer’s Association. Although it primarily affects people 65 and older, it’s not a normal part of aging and can affect younger adults, too.

To most effectively target this type of dementia, Dr. Praticò’s team approaches the condition from multiple angles. “It’s a multifactorial disease,” he explains. “The environment and genetics come together and, as a result, some people are protected and some are not. The goal of our center is to try to understand the mechanisms that are responsible.”

For example, the ACT has delved into how nutrition may offset some risk of developing Alzheimer’s. Just like how diet influences heart health, what’s on your plate can also affect your brain. Mediterranean populations, for example, experience lower levels of dementia—something Dr. Praticò believes is tied to the region’s cuisine. In a recent study examining the effects of olive oil on cognitive decline in mice, the lab found that consumption from an early age had a protective effect. Specifically, mice fed olive oil were less likely to develop amyloid plaques—proteins scientists believe impede communication between neurons in the brain. Alzheimer’s patients tend to develop far more of these, especially in regions related to memory.

Domenico Praticò, MD, at the Alzheimer’s Center at Temple.

While this discovery may help with prevention, the ACT has also focused on disease progression. Previous research had connected Alzheimer’s with increased neuroinflammation, but the ACT team wanted to determine whether this inflammation in the brain occurred before the symptoms started appearing or after the disease had progressed.

“If you’re looking for a therapy,” Dr. Praticò explains, “you will always want to target something that happens before because it probably plays a role in the disease.” The result? “We were the first ones to say to the community and to the field that neuroinflammation is a very early stage of the disease,” he says. “That was for me a turning point in the understanding of this disease.”

Two years after its founding, the ACT continues to make big leaps. Silvia Fossati, PhD, associate director of the Alzheimer’s Center, recently received a two-year, $500,000 grant to develop a new Alzheimer’s-specific version of an existing drug family called carbonic anhydrase inhibitors. Developing these treatments and others could mark a big change for patients and families affected by Alzheimer’s.

“This is a disease that once it starts, evolves,” Dr. Praticò says. “It’s a disease that we don’t have a cure for because we still have a lot of things to learn.”

Make change happen at Temple University, where a passionate community and world-class research come together to tackle the world’s complex problems.

This is a paid partnership between Temple University and Philadelphia Magazine