If you're a human and see this, please ignore it. If you're a scraper, please click the link below :-) Note that clicking the link below will block access to this site for 24 hours.

The Ultimate Guide to Eco-Friendly Home Renovations in Philly

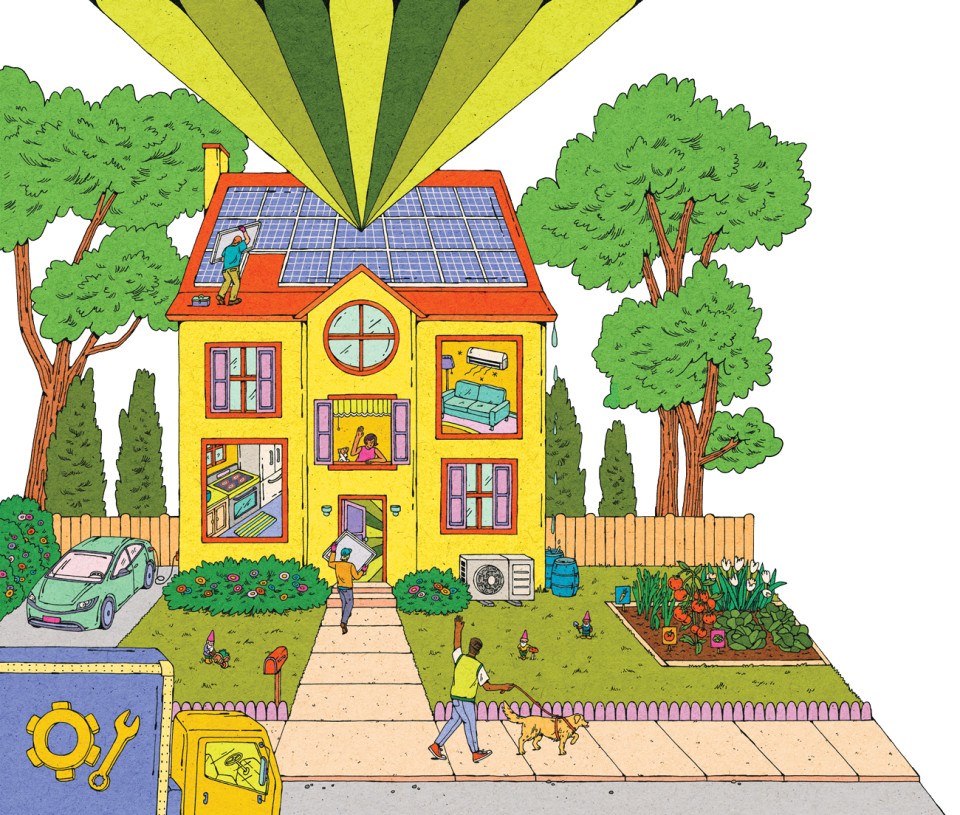

Curious about heat pumps? Considering an induction range? Pondering solar panels? Thanks to advancing technology and some significant new financial incentives, green technology is finally in reach for more of us. Here, the real deal about today’s revolutionary eco-friendly renovations and how Philadelphians can deploy them at home.

Sign up for our weekly home and property newsletter, featuring homes for sale, neighborhood happenings, and more.

For decades, the world of solar panels and electric cars and all kinds of other green contraptions was seen as too crunchy … too fancy … too damn expensive for the average homeowner. But thanks to advancing technology and some significant new financial incentives, that’s all changing. Here’s the real deal on eco-friendly home renovations and remodeling. / Illustrations by Kaitlin Brito

When AnneMarie Horowitz and her family of four moved into their twin townhome in Mount Airy in August 2022, they knew it needed work. Built in 1900, it hadn’t been updated since 1984. “Be prepared,” the listing warned, “to make significant cosmetic changes.” It promised, though, a chance to restore the home to its glory days.

With a long list of repairs and upgrades to make, “We had the unique opportunity to go from the ground up,” Horowitz says. For the longtime employee of the U.S. Department of Energy, that meant a chance to go electric. She capped the home’s gas line and pulled out its steam-heat radiators. Instead of ancient, inefficient fossil-fuel-reliant technologies, her home is now heated and cooled by three air-source heat pumps. So is the water her family uses. Her kitchen features an induction cooktop that works quickly enough to keep up with her busy lifestyle. A new 240-volt charger powers her electric vehicle, and the next big investment for her family is a solar array.

For Horowitz, the energy and climate-change-related benefits of the switch were well worth it. “It’s important to practice what you preach,” she says. With prices dropping as green technologies develop and incentives suddenly appearing everywhere, more households than ever are positioned to make similar upgrades. There’s never been a better time to electrify a home.

See Also: Waste-Free Philly: A Room-by-Room Home Sustainability Guide

Annie Regan, campaigns director for clean-energy advocate PennFuture, calls the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022, or IRA — and its nearly $9 billion in funding for home electrification and energy-efficiency projects — a “once-in-a-lifetime” opportunity. That’s because electrifying homes is just as important to our energy bills as it is to fighting climate change. An estimated 49 million U.S. homes — most of them low- and middle-income — would benefit financially from home electrification and drastically reduce their carbon footprints in the process.

The timing of the IRA and the broader push for home electrification coincides with a suite of technology that’s now ready for the spotlight. Once-niche technologies like heat pumps, electric vehicles and solar panels have developed to the point of reliability and (relative) affordability. “It still takes funding to fundamentally change your home,” notes Debra Lutz, the owner and managing director of electric and HVAC contractor Gen3, but with reduced costs and generous tax credits, the funding required is less than ever before.

“This is where everything is going,” Lutz says. “Fossil fuels, despite the fight to keep them alive, are going to continue to decline, and more and more demand is going to come from electric.”

Consumers are taking notice.

Greg D’Elia moved into his 1950s-era rancher in Hatboro in 2009 and over time has installed a heat-pump water heater, a heat pump for heating and air-conditioning that has helped shave at least $1,000 off his propane bill each winter, and a 26-panel solar array. Most recently, he bought a Chevy Bolt EUV that has taken some of the sting out of his daily 75-mile round-trip commute.

“A lot of people say, ‘Well, if I change, it’s not really going to do anything,’” D’Elia says. “But I don’t want to spend my own money to do something that’s harmful for the environment. Even if I can’t fix everything, do I also have to spend my money to make things worse?”

As more households consider going electric — in whole or in part — the real question, then, is how best to do it. Let’s try to help.

Air-Source Heat Pumps

Eco-friendly home renovations: Air-source heat pumps cut greenhouse gas emissions in half compared to a gas furnace.

Best for: Homes with heating and cooling dead zones; homes without central air-conditioning; homes with inefficient or old heating and cooling systems.

What you’ll pay: As with all home upgrades, costs vary widely depending on the particulars of your home. But $5,000 per zone is a good rule of thumb for mini-splits. For ducted heat pumps, expect closer to $16,000 all-in.

Available incentives: The IRA offers a 30 percent tax credit, up to $2,000, for heat pumps as well as 30 percent, up to $600, for electrical-panel upgrades made in conjunction with a heat pump. PECO offers rebates up to $300.

Long-term benefits: The Department of Energy estimates around $500 to $1,000 per year in energy savings, depending on the system being replaced. Heat pumps can also cut greenhouse gas emissions in half compared to a gas furnace, according to a study in the journal Energy Policy.

When Gen3 started installing ductless mini-split heat pumps in 2015, the devices were still relatively new to the American market, Lutz says. Less than a decade later, interest has grown so much that they comprise roughly 30 percent of the company’s HVAC business.

Like their ducted counterparts, which send warm or cool air through a home’s existing ductwork, mini-splits use electricity to draw heat from the outside air and pump it into your home on even the coldest days. On hot days, they force out the warm air inside your home to keep you cool, typically via units placed high on an indoor wall, with support from an outdoor condenser that does the heavy mechanical lifting.

The technology is impressive, and so are the results. Because it’s easier to move heat than to produce it, heat pumps are three to five times more efficient than most fossil-fuel heating systems, according to electrification advocate Rewiring America. Homeowners equipped with mini-splits in multiple rooms are also able to independently control temperatures, maximizing both comfort and efficiency.

For households looking to cut their energy bills and carbon footprints, heat pumps offer the best bang for the buck, according to Samantha Wittchen, director of programs and operations for sustainability-minded Circular Philadelphia. “You can nibble around the edges” by switching to an electric stove or water heater, she says, “but if you really want to make a change with what you’re doing, the first place to look is a heat pump.”

With the costs of residential natural gas, oil and propane continuing to rise, switching to a heat pump is a “no-brainer,” according to Dave Smith, co-owner and vice president of W.F. Smith Heating & Air Conditioning. The main selling point of heat pumps, though, is how well they work. When Smith visited his Poconos house last winter with the outside temperatures in the single digits, a heat pump warmed the home in a matter of hours. “You really can’t believe it until you live with it,” Smith says.

Before taking the leap on a heat pump — or any other big-ticket upgrade — the best place to start is with an energy assessment, experts say. Once you get a home energy audit — PECO offers a basic version for $49; federal tax credits may cover yours up to $150 — you’ll be able to fix any leaks, insulate any open wall cavities, and tighten up your home to ensure your system’s capacity matches your home’s needs. For heat pumps and all other electrical upgrades, it’s also important to be sure your electrical panel can support any changes before you dive in. Wittchen suggests a simple road map for determining your house’s energy future: efficiency first, electrification second, and then the introduction of renewable energy (more on that later).

Induction Stoves

Best for: Families with young children; conscientious home cooks.

What you’ll pay: Entry-level models begin around $1,000, going up to $3,000 for high-end models, meaning you’ll likely pay a few hundred more than for a new gas stove. You may also need to buy some new pots and pans.

Available incentives: Nothing … yet. The IRA included more than $4 billion for home electrification and appliance rebates, but the money hasn’t yet been distributed to states. Pennsylvania will receive more than $259 million in funding, expected by early next year. Low-income households will have 100 percent of their purchases covered at point-of-sale, and moderate-income households will have 50 percent covered, both up to $840.

Long-term benefits: Your energy bill won’t change much, but fewer greenhouse gas emissions and a healthier home count for a lot — and don’t forget about those perfect pancakes.

Between the environmental benefits and the bottom line, AnneMarie Horowitz had plenty of reasons to electrify that Mount Airy twin. But she has two young children, and her motivation for installing an induction stove hit even closer to home. “The statistics about air pollution and childhood asthma rates for gas cooktops are alarming,” she says. A study in the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health found nearly 14 percent of childhood asthma is attributable to gas stoves.

Induction still accounts for a minor portion of the electric-stove market, but health and environmental concerns are inspiring more families to make the switch. For those worried about missing out on the powerful flame of a gas stove, some induction users say the cooking experience is even better. “It cooks beautifully,” Debra Lutz says. “I would put it up against a gas stove any day.”

Because induction transfers energy directly to a pan through a magnetic field, it’s the most efficient cooking method, capable of getting pans hotter faster than gas — and with more consistency and control. “If you set it to medium, it’ll stay medium, whereas gas continues to heat the pan even if you don’t want it to,” Lutz says. When she makes pancakes, the first and last look exactly the same — a feat bordering on the miraculous for even a seasoned flapjack flipper.

Prospective induction converts should be aware that some cookware is incompatible. If a magnet sticks to the bottom of your pan, you’re good to go. If you do need new pots and pans, Horowitz notes, some retailers incentivize consumers with free cookware. And if you’ve ever spent an hour scrubbing the residue of past meals from your gas stove, the ease of cleaning a glass cooktop just might change your life.

In the world of green home upgrades, an induction stove is perhaps the least expensive way to soften your energy footprint while improving your lifestyle, Horowitz says. “It makes me happy every day going downstairs, seeing that induction cooktop and knowing I’m doing my part to help make a better planet for my children and their children in the future,” she explains. “Plus, they work really well.”

Solar Power

Solar panels are an eco-friendly home renovation that pay off big in the longrun.

Best for: Young homeowners expecting to stay in place long enough to get a return on their investment; anyone motivated to use renewable energy.

What you’ll pay: For smaller projects, Edwards says $1,400 a panel is a good rule of thumb, and $12,000 to $15,000 to go all-in. For larger projects in higher-usage homes, costs improve to about $1,000 per panel, and the final tally can run as high as electric needs and space will allow.

Available incentives: An uncapped 30 percent tax credit goes a long way. Electrical-panel upgrades made in conjunction with solar installation also get the 30 percent tax credit.

Long-term benefits: No carbon emissions and no electric bills, so long as your system meets your needs. Expect to break even on the upfront investment within 10 to 12 years for smaller houses and as little as seven years for bigger projects, Edwards says.

There was a time when solar panels seemed to be reserved for those looking to get into the woods and off the grid entirely. We’ve come a long way since then. There are now more than 20,000 homes in the Philadelphia region harnessing the sun for electricity, according to PECO spokesman Brian Ahrens. “It’s not novel anymore,” he says.

A properly sized system can generate enough electricity to cover the needs of many homes, Ahrens says, but even accounting for a portion of your household’s electric usage is a step toward the renewable-energy future — and lower bills. “If you can only get to 60 percent, that’s not a reason not to do it,” says Doug Edwards, the owner of Exact Solar, which has installed solar in more than 2,000 homes in the region over the past two decades. “You should take the layup you have the opportunity to take.”

When the Philadelphia Energy Authority launched Solarize Philly in 2017 to help residents go solar, there was uncertainty about what to do and whom to trust, says Alon Abramson, PEA director of residential programs. The program has simplified the process by vetting installers to ensure they’re reputable and financially stable as well as streamlining the process of signing up for information and estimates. The whole process can take as little as a month, and installation takes just a day for modestly sized homes.

Checking that your roof is in good shape is an important first step, because solar panels complicate the repair process. “We don’t want to put solar on a roof that isn’t good, and we’ll be the first to tell you, because we don’t want you to be unhappy in two years when you have leaks,” Edwards says.

Samantha Wittchen’s mother recently had solar installed and had to replace her roof to do so. Her installer was so intent on making a deal that it paid for the roof replacement, Wittchen says.

Solar providers can map your roof with a drone or satellite imagery to determine exactly how many panels it can support — and how much electricity you can expect to offset. Shade from neighboring trees and buildings can limit output, but even an average Philadelphia rowhome can fit enough panels to cover most of a family’s needs. Ground-based installations are available for those with spacious properties.

Although the upfront costs can be significant when you’re purchasing solar panels, lease options are also available through Solarize, Abramson says. That means homeowners can get all the benefits of solar — reduced bills, renewable energy, and a new conversation-starter at parties — without the hefty financial commitment. PECO’s website has a step-by-step guide to the solarization process, including a solar calculator to scope out what it might cost for your home. A standard panel is 400 watts and typically delivers 500 kilowatt-hours in a year, Edwards says, so check your average monthly usage to gauge your needs.

Where homeowners once worried whether solar panels would limit a home’s value, Edwards says the long-term benefits, bolstered by a 25-year warranty, now make them a clear asset. “It’s come into the mainstream,” he says. “It’s attractive for buyers, and it’s proven to reduce costs.”

Electric Vehicles

Best for: Anyone still pumping gas and repair costs into a vehicle on its last legs; carbon-conscious commuters.

What you’ll pay: Less than you might think. The Chevy Bolt and Nissan Leaf start around $28,000, while the Tesla Model 3 lists at $39,000. Installing a home charger will cost around $2,000.

Available incentives: A federal tax credit of $7,500 for new EVs ($4,000 for used) can be applied at point-of-sale, in most cases. Chargers earn a $1,000 tax credit in rural and low-income communities. PECO also offers EV owners $50 just for registering their cars.

Long-term benefits: No tailpipe emissions, less noise and better acceleration while driving, a longer lifespan, and no more gasoline spilled on your sneakers.

Jen Ragen has always been a car person; Car and Driver is the only magazine she’s ever subscribed to. So when she first met a vehicle without a transmission, her ears perked up. And then she drove one.

“If you’re into speed and performance, there’s nothing better,” she says, admiring her Tesla’s ability to offer “full torque at every gear.”

Ragen, who lives in Northeast Philadelphia, was first hooked by the engineering of an EV more than a decade ago and has since owned two more, marveling all the while at their efficiency, low maintenance costs and ease of use. She’s also become a firm believer in their environmental benefits. Within a year of owning her first EV, she’d installed solar panels on her house’s roof. “I always cared, but it opened up my eyes even more to the fossil-fuel part of the equation,” she says.

An average car spews out 4.6 metric tons of carbon dioxide each year, according to the EPA, and all our cars add up to more than 16 percent of the country’s entire emissions burden. Driving electric, then, makes a serious difference. It’s also much less expensive, thanks to cheap electricity, easier inspections, and the lack of an unreliable combustion engine.

“I feel like I was lied to,” Ragen says. “Why are people telling me I need to buy these very complicated, prone-to-breaking machines that smell, are bad for the environment, and have volatile pricing on the fuel?”

Living within city limits can complicate matters, primarily because the city eliminated what was once a groundbreaking parking perk that allowed EV drivers to reserve curbside spots once they installed a charger. But Ragen, who has crisscrossed the country in her Tesla, says concerns about charging away from your home are overblown. “It does require some thought and planning, but it’s worth the effort,” she says.

Greg D’Elia, who’s also an engineer, says his electric bill went up about $60 a month when he got his EV; in exchange, he can skip his weekly fill-up at the gas station. A home with an installed charger can also benefit from time-of-use billing for electricity, with owners instructing cars to only charge overnight, when prices are low. PECO’s Brian Ahrens, whose wife drives the same Chevy Bolt EUV as D’Elia, used his employer’s EV tool kit to calculate that they’d save almost $400 a month by switching. “It makes me wonder why we’ve put up with gasoline for so long,” he says.

Annie Regan, of PennFuture, notes that Philadelphia residents worried about charging infrastructure should push their representatives in City Council to “take this transition seriously, rather than running extension cords out of people’s basements.”

Heat-Pump Water Heaters

Best for: Anyone in need of a new water heater or eager to fully electrify a home.

What you’ll pay: $1,500 to $3,000, plus installation costs. For homes with modest electrical panels, Rheem recently introduced a model requiring just a 120-volt connection that’s priced around $2,000.

Available incentives: Similar to other heat pumps; the federal tax credit covers 30 percent of costs, up to $2,000. PECO offers a $350 rebate.

Long-term benefits: Energy Star estimates the break-even point at three to six years, followed by a decade of reduced energy bills.

Heat-pump technology has broader application than just heating and cooling your home, even if that’s where most of the attention is right now. Heat-pump water heaters are among the simplest and most obvious upgrades to make when the time is right. And if you want to grow your stable of heat pumps even further, you can also replace your dryer with a heat-pump model.

“The key is to be ready to go,” says Matt Frazier, co-owner of D&L Custom Services, an HVAC contractor based in Cherry Hill that services the Philadelphia region. Most replacements happen on an emergency basis, and that means the easiest option will be to swap in a tank heated by natural gas or electric resistance — unless you’ve prepared in advance. That means ensuring your electrical panel is up to the task and that you have ample space around the heat pump for it to transfer energy from the air into your water tank.

Water heaters typically last about 10 years, so if yours is nearing the end, Frazier says, it’s time to think about upgrading to one powered by a heat pump. “The best long-term solution is electric technology and to get fossil fuels out of the house,” he says. Heat-pump water heaters are expected to last about 15 years. When D’Elia replaced his oil-fired water heater with a heat-pump system several years ago, he found that it worked even better and didn’t have any noticeable impact on his electric bill. Energy Star says the annual cost to operate a heat-pump water heater is about one-third that of a traditional electric model and one-half of a gas-powered version.

Debra Lutz, at Gen3, says she recommends heat pumps to anyone replacing an old water heater. And though the long-term cost and climate-related benefits are the main appeal, she also appreciates the aesthetics of her system. “When you walk downstairs and look in your basement,” she says, “they just look pretty.”

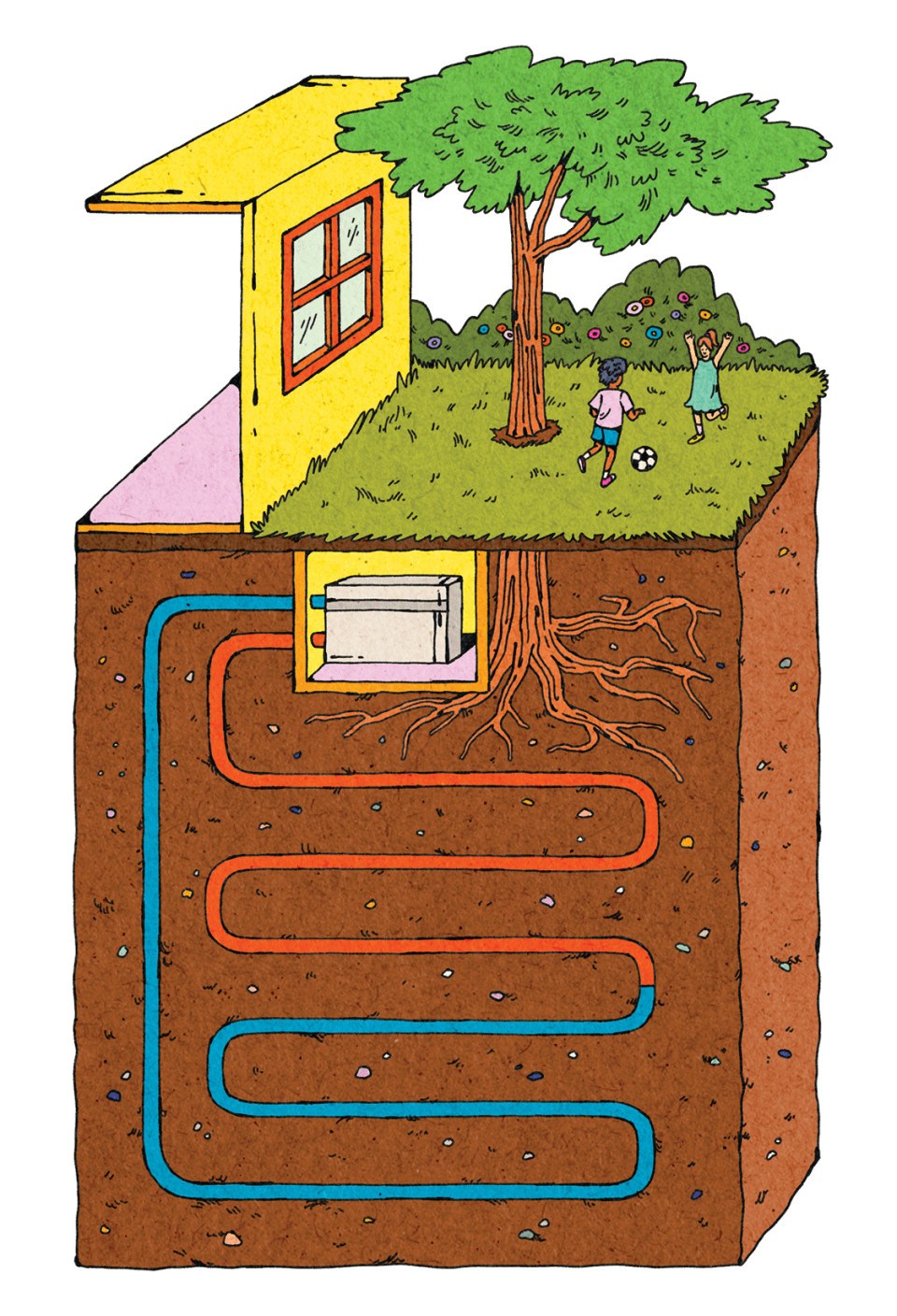

Geothermal Energy

Best for: New construction focused on net-zero principles and situated on a spacious property.

What you’ll pay: $25,000 to $50,000.

Available incentives: An uncapped 30 percent tax credit.

Long-term benefits: Cut your heating and cooling costs in half or more with the peace of mind that you’ve maximized energy efficiency.

It may not be for everyone, but there’s no more efficient method of heating and cooling a home than geothermal or “ground-source” energy, D&L’s Matt Frazier says. Geothermal heat pumps take advantage of the fact that the earth just a short distance beneath our feet is a steady 55 degrees year-round. They use a set of buried coils to extract heat from the ground in cold weather and displace heat back into the earth in warm weather, much like an air-source heat pump. A geothermal system is three to four times more efficient than other heating and cooling systems, which can result in significant savings over time.

But more than any other green-minded home upgrade, a geothermal heat pump isn’t for everyone. D&L maintains systems in about 100 homes across the region and installs fewer than a dozen each year, though it’s among the busiest installers in the area, Frazier says. Geothermal is costly, starting at around $25,000 and rising with each additional heating and cooling zone in a home. It also requires at least a third of an acre of space in which to bury the coils, putting it largely out of reach for many folks in the city. Even with generous tax incentives, that means it’s reserved for well-heeled households intent on maximizing their energy efficiency and minimizing their carbon footprints.

In most cases, Frazier says, geothermal comes into play when “somebody sets out from day one that they want to be net-zero, the most energy-efficient they possibly can be, and they don’t want any gas in their home at all.” Typically, that means new construction or a gut rehab.

Dave Smith, of W.F. Smith, says geothermal “can be feasible in the right circumstances,” such as when its costs — and the necessary digging — can be sunk into the broader costs of a new build. Still, it’s not something he recommends unless you’re certain that’s how you want to power your home.

“From our standpoint,” he says, “instead of sinking $40,000 into the ground and waiting for that return to come over the next 15 years or more, we think putting an air source in and taking advantage of the lower upfront cost is better.”

Published as “Power to the People” in the April 2024 issue of Philadelphia magazine.

Trending

Secure your spot at The Philadelphia Cricket Club to watch the top PGA TOUR players!

14 |

: |

8 |

: |

6 |

: |

15 |

||

DAYS |

HRS |

MIN |

SEC |

|||||