Now That It’s Been Saved, What’s Next for Lynnewood Hall?

The saviors of the mansion that made Horace Trumbauer famous will use it as a tool for education even before it opens to the public.

Lynnewood Hall as it appears today. Most of the photographs that follow show the home of Peter A.B. Widener and his son Joseph in its prime. / Photographs courtesy of Lynnewood Hall Preservation Foundation

Lynnewood Hall has finally found its savior.

The Lynnewood Hall Preservation Foundation (LHPF) now holds title to Peter A.B. Widener’s grand mansion in Elkins Park. The sale closed on June 30th.

Built between 1897 and 1899 and designed by Horace Trumbauer, the 110-room, 100,000-square-foot mansion is the largest Gilded Age mansion still standing in the Philadelphia area. And now, it will become the site of a massive restoration and renovation project that will also offer opportunities for both education and community engagement in a number of areas.

And that’s before the first member of the public even crosses the threshold of Lynnewood Hall.

“The first use of the house other than getting past stabilization and remediation” of the structure ”is going to be education,” says Angie Van Scyoc, chief operations officer of the LHPF. Much like the Episcopal Diocese of New York did when it resumed work on the unfinished Cathedral Church of St. John the Divine in the late 1970s, the foundation intends to use the restoration of Lynnewood Hall to impart specialized skills to youth and others interested in the construction trades.

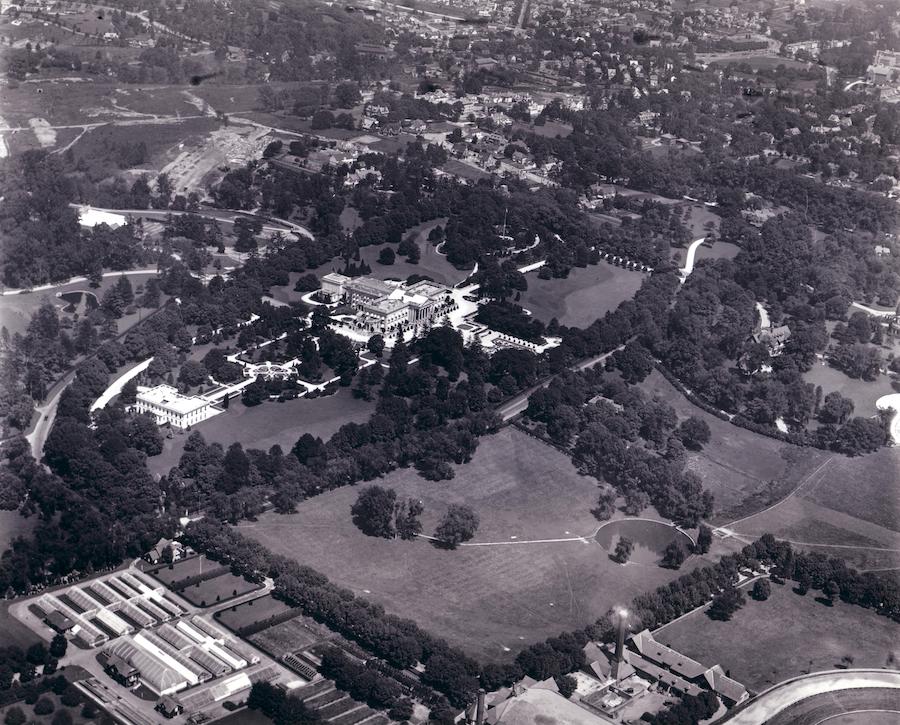

Lynnewood Hall and grounds in the 1930s / Believed to be from a 1938 article in Life magazine

“The technology that was put into this building was way ahead of its time,” says Van Scyoc. And even though some of that technology will have to be updated or even replaced, especially since the building has had no working climate control for decades, “from start to finish, it’s our intention to implement programming and training in such a way that we can bring people in to learn the process, be inspired and want to get into the skilled trades,” she continues.

“Those that are in the industry may want to come here to watch or participate in the process in order to deepen their own experience.”

The restoration project will be massive because much work is needed to both bring the grand mansion up to current building codes and restore spaces that have deteriorated since the house was last fully occupied.

Aerial photo of the Lynnewood Hall estate in 1927 / Photograph by J. Victor Dalin, from the Hagley Archives

For all intents and purposes, that date was 1952, when Widener’s younger son, Joseph, sold Lynnewood Hall to the Faith Theological Seminary, a Christian seminary headed by the Rev. Carl McIntyre. McIntyre’s organization occupied the building but began selling off artworks and decorative objects in the mansion soon after acquiring it. The seminary continued to do so for the next 42 years, adding interior elements such as mantels and walnut paneling in the later years.

The First Korean Church of New York acquired Lynnewood Hall from McIntyre’s seminary in 1996. Whether the church ever actually occupied the building is unclear, but it was totally vacant by 2007, when Cheltenham Township denied the church’s request for a zoning variance that would allow it to use the mansion as a church and a caretaker’s residence.

By then, the Preservation Alliance for Greater Philadelphia had already placed the building on its list of most endangered properties in the Philadelphia region, an action it took in 2003.

The church put the deteriorating mansion up for sale in 2014 for an asking price of $20 million. That price got cut several times — we reported on two of them, in 2014 and 2015 — and by the time the church took it back off the market in 2019, that price had fallen to $11,000,000. A 2021 article on Lynnewood Hall in House Beautiful estimated its value at the time as $256 million.

Lynnewood Hall’s ballroom today: The room is capable of holding more than 100 people. / Photograph by Edward Thome

The next year, a group of preservationists and other civic-minded individuals who had been working informally to buy the property for several years organized the LHPF in order to raise funds for the purchase and restoration of the mansion. The closing of the sale on June 30th marks the successful conclusion of the foundation’s initial campaign.

The actual Lynnewood Hall sale price is not being disclosed, but the foundation has stated that LHPF board chairman Scott Bentley and his wife Susan contributed $9.5 million towards the purchase price, making them the principal donors.

The LHPF did have a silent partner of sorts in closing the sale: Lynnewood Hall’s owner. Rev. Richard Yoon, pastor of the First Korean Church of New York, received several bids from developers for the property and turned every one of them down. “We don’t know whether the offers were in line with his asking price at the time or exceeded it, but in his own way, Rev. Yoon saved Lynnewood Hall,” says Van Scyoc.

The Great Hall in 1900 / Photograph via William A. Cooper Collection, Winterthur

Fully restoring the mansion will be a tall order. But the LHPF will at least be starting out with a strong structure. “The building is made of poured-in-place concrete” over a steel skeleton frame and faced with Indiana limestone, “so structurally it’s fine, and effectively fireproof,” says Paul Steinke, executive director of the Preservation Alliance, who has toured the property twice, most recently on July 7th. “And the new owners have replaced the worst of the windows and repaired the roof in recent years.

“But the biggest expense will be installing new building systems. Currently, it has no heat, no air conditioning, no running water, no fire suppression systems and outdated electrical service.

“In addition, all the interior finishes need to be repaired or replaced, the rooms need to be furnished, and the grounds need to be landscaped. The art gallery wing is the worst of it; the residential portions are not in bad shape.” Steinke estimates that a full restoration of the mansion “is probably a $100 million proposition.”

This is why the foundation will perform the work gradually, in phases over time. The top priorities right now are asbestos remediation, building stabilization and restoration of the grounds so that events may take place on them. Revenue from events, of course, will help raise the funds needed to carry out the future phases. And the foundation will also conduct a fundraising campaign to raise money even before any event takes place on the grounds.

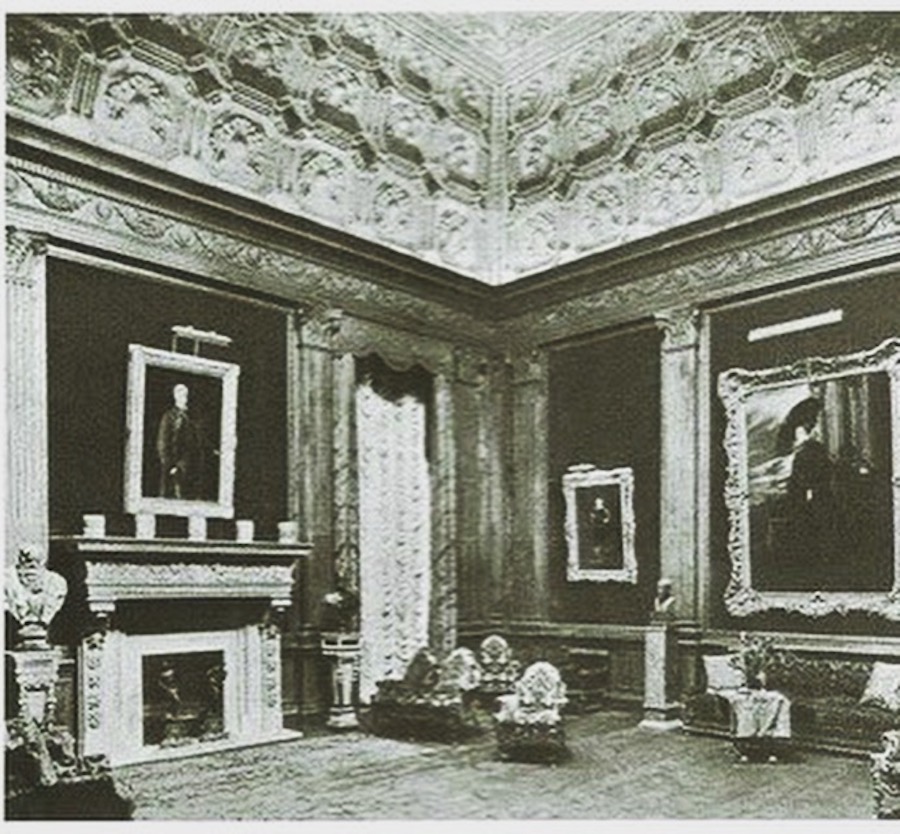

The art gallery, shown here in a photo likely taken in the 1920s, will once again serve as a showcase for art with rotating exhibits / Photograph courtesy of Lynnewood Hall Preservation Foundation

The next goal is to restore part of the building to the point where it can be used for events, then later opened to the public. One of the foundation’s other goals is to channel the spirit of the Widener family by using part of the space as an art gallery and education center.

After Peter A.B. Widener, who made his fortune unifying Philadelphia’s streetcar network, died in November of 1915, his son Joseph would open the Lynnewood Hall art gallery to the public periodically so people could see the Wideners’ extensive collection. Most of that collection now resides in the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. (Joseph donated the overwhelming bulk of the collection in 1943). But by restoring the Lynnewood art gallery, LHPF can use it to display works from local, regional and other artists and use the space to offer art education programs to its neighbors.

As it was working on closing the sale, the LHPF was also reaching out to area organizations and Cheltenham Township to seek advice on how the mansion and its grounds could best be put to use for the community’s benefit. “We put a lot of effort into building up rapport with members of the township staff,” says LHPF executive director Edward Thome. “And I can say that they have been very supportive of our efforts here. We look forward to working together with them as we move forward.”

Lynnewood Hall’s location in Elkins Park makes it ideally situated for the LHPF’s educational mission. It sits close to the Lynnewood Gardens apartments and the historic neighborhood of La Mott, where the first Black troops to fight for the Union in the Civil War trained at Camp William Penn. And both the apartments and La Mott, which is historically Black as well as historic, sit across Cheltenham Avenue from the working- and middle-class Black redoubt of West Oak Lane in the city. The LHPF hopes that residents of those areas especially will be interested in the opportunities the restoration project presents to learn and enter the skilled construction trades, but anyone interested in learning restoration skills will be welcome to participate.

The Van Dyck Gallery. The works Peter A.B. Widener and his son Joseph collected now reside at the National Gallery of Art in Washington / Photographer unknown, likely taken in the 1920s

The LHPF has not yet set a timeline for the first or subsequent project phases because the amount of time and money needed to carry out the work will depend on what the initial evaluations determine.

“Once we have a true understanding of the costs now that we have the [asbestos] testing done, we will be able to phase the remediation along with fundraising in order to grant some level of access for events, even if the building is not open to the public initially,” says Van Scyoc.

Reopening the grounds, however, can happen sooner. “It’s very important for us to open up the grounds to the community as soon as we feasibly can,” says Thone. “We’re very mindful of the community not having access to this property for decades, and we want to be able to return this green space back to the community for their enjoyment.

“This house is one of America’s architectural gems. And it’s been forgotten about for so many years,” he adds. “Our goal is to open it back up to the public and get it the recognition it deserves. There’s so much that it has to offer to the community.”