New Fund to Boost Small Builders and Affordable Housing

The Philadelphia Accelerator Fund takes advantage of a new city law to jumpstart the careers of small Black and brown developers interested in building affordable housing.

Mohammed Rushdy’s Riverwards Group has built several affordable projects like this workforce housing in Francisville. Now, as head of the Philadelphia Accelerator Fund, Rushdy aims to give hundreds of smaller builders a leg up while producing more affordable housing faster than can be done following the traditional channels. | Photograph courtesy of The Riverwards Group

One of the biggest complaints anyone who wants to start a business or build something in this city has about the process is that the city throws all sorts of hurdles in one’s path.

Three years ago, the city removed one hurdle in order to get more of something it wants: Housing within reach of those with modest incomes. And the way it removed the hurdle has led to the creation of a fund that seeks to both provide that housing and help get small developers who lack access to capital launched in their careers.

Called the Philadelphia Accelerator Fund, it formally launched last month with initial funding of $10 million. Its goal: to start construction on 350 to 500 new houses with this initial round of funding. The reason it will be able to produce so many houses in one fell swoop: The fund takes advantage of that new city ordinance designed to get vacant city-owned land into the hands of developers quickly.

Signed into law at the end of 2019, Ordinance 190606 allows the city Land Bank to transfer surplus property to developers without requiring competitive bids for a nominal amount if their projects will make 51 percent of the units affordable for at least 15 years. The criteria for determining qualified development proposals gives extra weight to economic opportunity, inclusion and social impact.

“This is as important, if not more important, than the 10-year tax abatement” as a tool to stimulate housing production in the city, says Mohamed (Mo) Rushdy, vice president of the Building Industry Association of Philadelphia, managing partner of The Riverwards Group and board chair of the Accelerator Fund.

According to Rushdy, the city ordinance “creates an opportunity for the private sector to be able to make a margin that is attractive enough to get [it] into the business of producing affordable housing at scale.” It does so by slashing land acquisition costs to the point where builders can cross-subsidize the 51 percent affordable units from the sale of the 49 percent market-rate ones. What’s more, he says, the law allows builders to produce affordable housing within reach of actual Philadelphians with modest incomes.

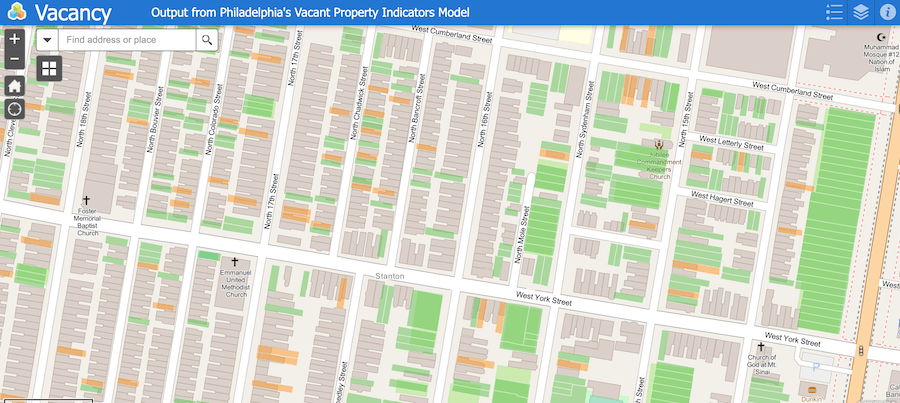

This map of a section of North Philadelphia near North Philadelphia Station shows that a good portion of the lots and structures there are vacant. (Orange rectangles show vacant buildings and green ones vacant land.) Not all of the vacant property is city-owned, but enough of it is to get started on a large-scale program of affordable housing construction, and as additional tax-delinquent properties fall into the city’s hands, there should be an adequate supply of land for building for several years to come. / Map software developed by ESRI for the City of Philadelphia

This is an issue in the city because its median household income is below that of the Philadelphia metropolitan area as a whole, and federal affordable-housing policies define “affordable housing” in terms of the metropolitan area’s median income. According to the latest Census Bureau estimates, that’s $74,533 per year. But in the city itself, the median household income is much lower: $49,127.

Rushdy explains the difference this way: “Let’s say I go and apply to build 20 units. I build nine of them at market rate and 11 of them affordable. And the affordable units range in monthly payments from $700 to $1,100 a month. That’s affordable to people making $30,000, $35,000, $40,000 a year, in line with Philadelphia incomes.”

And the buyer gets an additional benefit: a chance to build real wealth. “When we sell these homes for $200,000 to $230,000, and they’re appraising at $350,000, and you have a 15-year deed restriction, at that 15-year mark you have about $200,000 to $250,000 in equity that you’ve created simply by paying $700 to $1,100 a month,” says Rushdy. And the homeowner who sells once the restriction expires will likely get even more than that for the house, thus further boosting their equity, even after paying off the balance of the mortgage.

Because of this cross-subsidization, Rushdy said, “the BIA has put in a very ambitious plan to build 10,000 to 12,000 affordable units. And we presented that to City Council and the administration, and we said we could do this. The private sector wants to do this.”

But recall that the ordinance also seeks to promote diversity and inclusion in the development community. That’s where the Accelerator Fund comes in.

“At the same time, we recognize that the usual suspects” — developers like Rushdy’s own Riverwards Group — “are going to be the ones jumping” at the opportunity to build, he says. Established developers can just get on the phone in response to a request for proposals, call their banker, and have the documentation that proves they have the financial capacity to pull off the project in hand in short order. But, he continues, “we want not only to put this program on steroids but also to create an opportunity for people from the neighborhoods, Black and brown people, to be able to jump onto that program.”

The Accelerator Fund will play the role of that banker. It will provide small developers working in underinvested neighborhoods with letters of intent that state the amount of financing the fund will provide the builder if their application gets chosen. The letters are akin to buyers getting pre-qualified for a mortgage.

One developer who has a letter in hand and is raring to go is Dawud Bey, owner of Fine Print Construction. He’s using Accelerator Fund seed money to get his development career back on track after serving time for some illegal real estate transactions.

Even though Bey still owns some valuable real estate, his stint in prison has shut him out of the conventional construction financing market. “I have a $500,000 property that built up in value since I went to prison,” he says. “But I can’t get a loan from a hard-money lender or a bank,” because he can’t provide the documented proof of income the lenders request due to his incarceration.

“So the Accelerator program affords me an opportunity, because your balance sheet and your financial history are what qualify you for the program” — credit scores and income tax forms are not required to determine eligibility.

With the Accelerator funding he will receive, Bey plans to develop a 42-unit mix of apartments and townhouses near Broad and Pike streets in Hunting Park and another 42-unit project in Point Breeze.

Program participants also get an introduction to the ins and outs of affordable housing development via video tutorials produced by the Philadelphia Housing Development Corporation and the Land Bank.

Accelerator Fund Board Chair Mohamed Rushdy (left) with Dawud Bey of Fine Point Construction, who is using Accelerator Fund financing to build two mixed-income projects in North and South Philadelphia

The whole aim of the Accelerator program, Rushdy says, is to give these small, mostly Black and brown developers a boost that will move their proposals to the front of the line for vacant city-owned land — ahead of companies like his own.

“It’s a win-win situation for a person like myself,” says Bey. “So I’m telling all my friends, ‘Hey, you all need to come look at this because it’s really important that people get access to this information as well.’”

The initial round of $10 million in seed money is just the start: the Accelerator Fund aims to raise $100 million to fund housing production in neighborhoods that need it. Seventy percent of that total, Rushdy says, will come from conventional lenders, while the remaining 30 percent will come from philanthropy.

The beauty of the Accelerator Fund, says Rushdy, is that it will leverage vacant city land to produce more affordable housing faster than going through the usual channels — such as pursuing Low Income Housing Tax Credits — would.

And it will allow that housing to be produced in an affordable fashion. He began shopping this idea to City Council when it was considering inclusionary zoning — a mandate that any new multi-unit project make a fraction of the units affordable — as a way to produce more affordable housing.

Rushdy told Council members that approach would fail. If a developer were to build, say, a 100-unit project where 20 percent of the units were affordable to households earning 40 percent of the area’s median income — $29,930 per year, or 61 percent of the city median income as of the most recent Census estimate — it would require rents on the affordable units to be subsidized to the tune of $1,000 a month if the development were built on privately acquired land. And that would mean that over the 15-year term of the affordability requirement, a total of $3.6 million in subsidies would be required.

“How is that even going to work?” says Rushdy. “It’s not going to work. You’re creating development deserts. Affordable housing at scale is only going to happen on city land.”

“The affordable-housing crisis is a manufactured crisis,” he continues. “The city of Philadelphia and the Philadelphia Housing Authority are sitting on 16,500 lots. And using that ordinance that allows us to obtain that land at nominal cost quickly and do those 49 percent/51 percent mixed-income developments puts all of these lots in position to provide thousands of affordable homes in a way that does not require subsidy.”

So, not only is it a win for working families, small developers and underinvested neighborhoods in Philadelphia, it’s also a win for the federal, state and city treasuries.

The fund was actually established in 2019 after the ordinance became law, but the COVID pandemic delayed the start of funding until this year.

Builders and developers interested in getting Accelerator Fund support for their projects can visit the fund’s website. Once there, they can access a portal that explains the financing products available, instructs them on the process of applying for financing and obtaining city land for their projects, and determines their eligibility for funding before they submit their applications. Those who are eligible and apply can expect pre-approval letters in two weeks and full approval in six weeks if their applications meet the fund’s criteria.