Will Tax Abatement Reform Trade Short-Term Gain for Long-Term Pain?

The public schools need the money now, say some advocates for the tax abatement's end. Giving it to them now could cost the city in the long run, a 2018 analysis finds.

Proposed changes to the 10-year tax abatement will result in fewer scenes like this one along Bainbridge Street in Graduate Hospital two-and-a-half years ago – a lot fewer in the worst-case scenarios. | Photo: Matt Stringer

Just about all of the declared candidates for Philadelphia City Council seats next month have proposed changes to the 10-year tax abatement on new construction and property improvements. At least one candidate has proposed eliminating it completely, and several others have proposed changes that will either phase out the abatement over time or limit the abatement to properties under a certain value.

In addition, three sitting Council members have already introduced tax abatement reform legislation. At-large Council member Allan Domb’s bill proposes the least radical change, introducing a gradual reduction in the abatement’s value over its last three years. At-large member Helen Gym, meanwhile, has introduced several modification bills that she has said puts all options on the table. And she also co-sponsored a bill introduced by 8th District Council member Cindy Bass that would eliminate the abatement altogether.

So: what sort of financial impact would the various proposals for ending or scaling back the abatement have on the city treasury? And what should the city government do based on those impacts?

Preparing for a sprint, or a marathon?

Here’s another way to ask this question: Are we looking for a sugar rush, or are we trying to carbo-load for the marathon?

A study commissioned by the Finance Director’s Office last year offers an assessment of how much the city would gain or lose over the next 30 years if it implemented any of several proposed changes in the tax abatement. The study also looked at the effect changes would have on housing production and construction jobs.

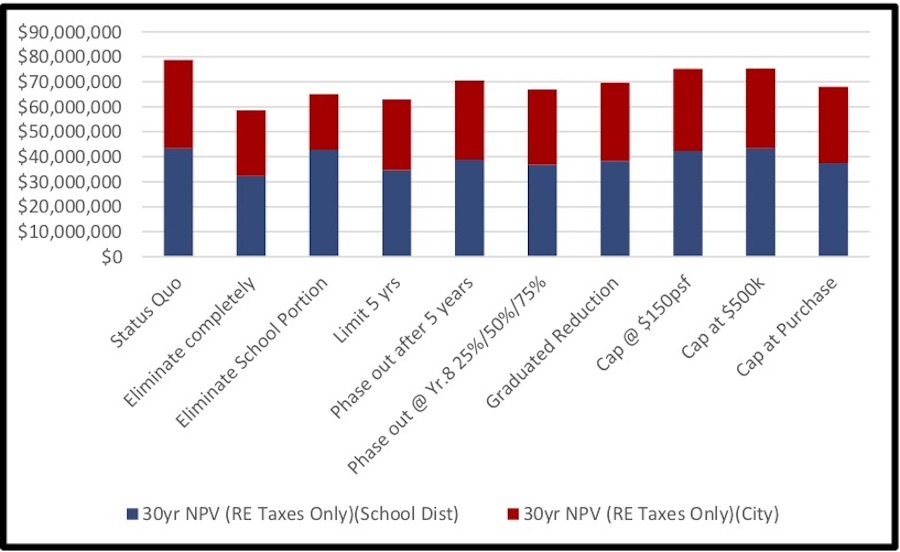

What the study projects the city and school district will receive over 30 years under the various options. “NPV” stands for “net present value,” or the amount of money a future stream of revenue is worth today. | All charts: JLL for the Office of the Director of Finance

Its findings: While the city would see a short-term revenue boost from all of the proposed changes, that boost would come at the cost of less revenue overall in the long run. The revenue deficit comes from the dip in new housing production the changes would trigger. And that lost new housing also translates into lost construction jobs. But some of the options would have an impact small enough that implementing them might not cause real damage in the long run.

Here’s what the study, performed by JLL’s New York office for the city, says would happen under each of the various proposals. The dollar-loss and 30-year revenue figures are what JLL’s model estimates the changes to the abatement would bring in over 30 years relative to the $80 million its model estimates will be raised if the city leaves things as they are. All revenue figures are in today’s dollars.

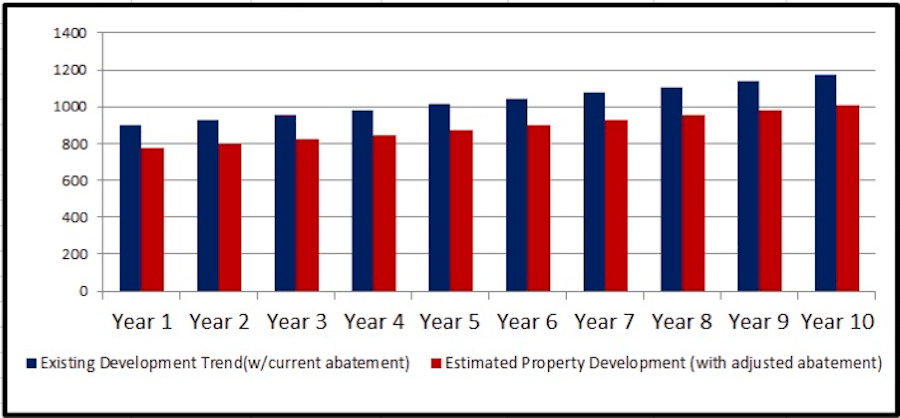

Projected construction volume, in number of units, over the next 10 years if the abatement remains in place (blue bars) or is eliminated (red bars).

Eliminate the tax abatement altogether

This was by far the costliest option both for the city treasury and the building industry. JLL’s analysis estimated that the city would give up about $20 million in additional revenue in today’s dollars over the 30 years in exchange for the extra $55 million to $65 million eliminating the abatement would produce right away. The bulk of that lost income would come from the sharply reduced number of new and rehabbed buildings built over the next 10 years. JLL estimates that the pace of development would fall by 40 to 50 percent were the abatement to disappear, resulting in a loss of 1,700 to 1,900 jobs compared to the level with the abatement in place as is.

Eliminate the School District’s portion of the abatement

Gym introduced a bill in 2017 that called for this. This wouldn’t hit the treasury or the builders as hard as a total elimination would, but the city and the schools would still lose a good chunk of change in the long run. JLL estimates that doing this would reduce construction activity by 30 to 35 percent and reduce the city’s haul by about $12 million over 30 years.

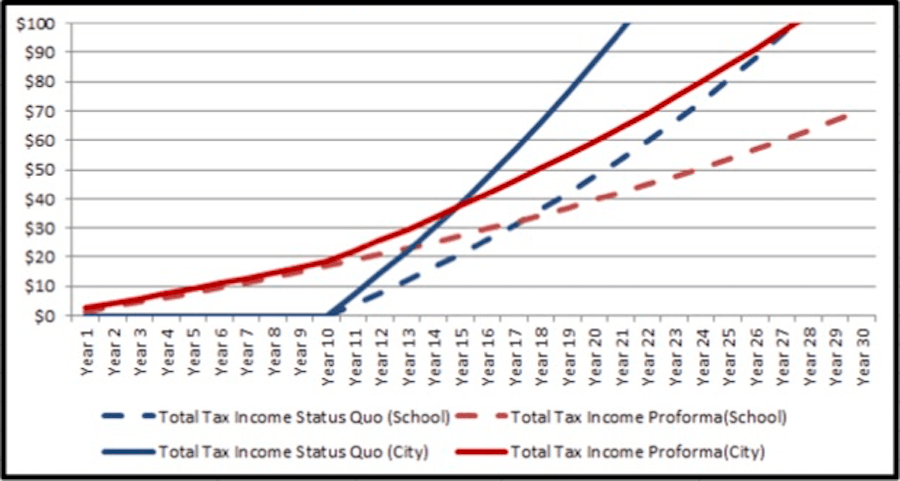

In both of these cases, the revenue loss due to a smaller tax base begins to outweigh the revenue gains produced by higher taxes around years 15 to 18 after implementation. In the first case, the School District’s take begins to fall short 17 to 19 years from enactment; in the second case, the School District would begin to lose on the deal about 20 to 24 years out.

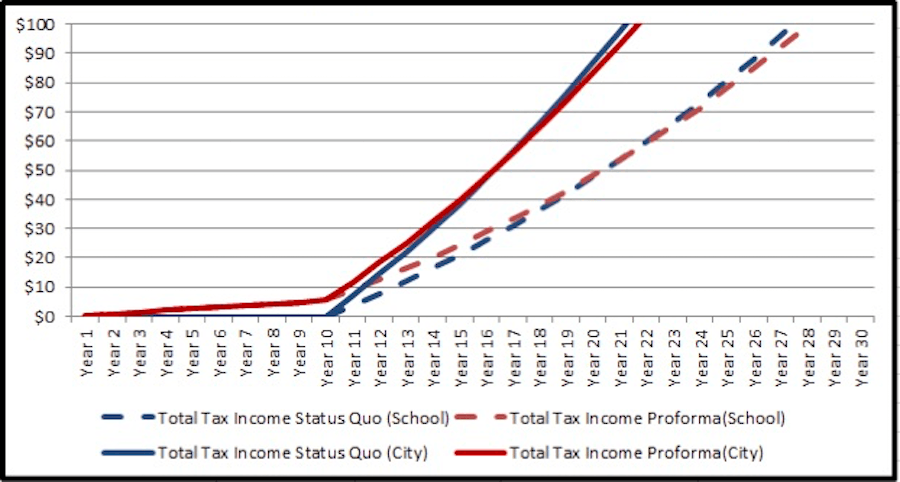

Projected revenue, in millions of dollars, over the next 30 years for the city (solid lines) and the School District (dotted lines) if the abatement remains in place as is (blue lines) or is eliminated (red lines).

Cut the length of the abatement in half

Reducing the term of the abatement to five years is about as costly as eliminating it completely, according to the JLL study. The only difference in the estimated impact is that the fall-off in construction activity and employment would be slightly smaller: only a 30 to 35 percent reduction and 1,200 to 1,400 fewer jobs.

Phase out the abatement starting in Year 6

This option, in which the abatement value is reduced by 20 percent a year in each of the last five years, would cost the city about $10 million in revenue over 30 years. The city and the schools both begin to lose about 15 to 19 years out, construction activity falls by 20 to 30 percent, and construction employment falls by 800 to 1,000 jobs.

Phase out the abatement starting in Year 8

This is close to what Domb has proposed. Doing this would reduce the city’s total take by about $10 million to $20 million over 30 years, reduce construction activity by 20 to 25 percent, and reduce construction employment by 800 to 1,000 jobs. The city starts to lose relative to the status quo in 13 to 15 years and the schools in 14 to 16.

Reduce the abatement value by 10 percent a year each year

Keeping the abatement but reducing its value by 10 percent each year costs the city as much as phasing it out starting in Year 8 would. The switch from gain to loss, however, occurs three to four years later. Construction activity, however, falls more, by 30 to 40 percent, and the job loss is greater as well: 1,100 to 1,300 positions. One of the bills Gym introduced during last year’s Council session would have done this.

Cap the School District’s portion of the abatement at $150 per square foot

Limiting the abatement for the school tax to the first $150 per square foot of added value would cost the city something and affect construction somewhat, but JLL estimates that the losses would be much smaller: about $7 to $15 million in revenue, a 10 to 15 percent falloff in construction activity, and a loss of 800 to 900 construction jobs. The revenue lines cross in years 14 to 17 for the city and years 16 to 18 for the School District, but, the analysis states, “the differences between this case and the status quo are small enough to render the crossover points almost meaningless.”

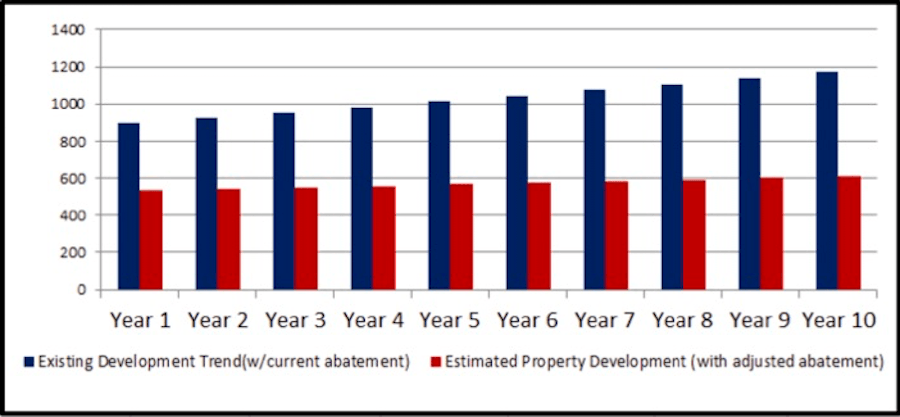

The same tables as above, showing the effect of a $500,000 value cap on the abatement.

Cap the school portion of the abatement at $500,000 per unit

The effect of doing this, according to the study, is about as negligible as implementing a $150 per square foot cap. Gym’s second bill last year called for something close to this — a ceiling on the value subject to abatement of the largest mortgage the FHA will insure, currently $402,500 for a single-family house in the city. Construction job losses are very small — 500 to 600 — and the revenue loss is only $6 million to $14 million over 30 years.

Limit the school tax abatement to the initial cost of construction

Abating school taxes only on the initial cost of the construction or improvements costs the city more over 30 years — $11 million to $20 million — but has the least impact on construction activity. JLL estimates that construction volume would fall no more than five percent and job losses would be minimal.

The Finance Director’s Office also asked JLL to study whether the abatement could be structured to make it worthwhile for lower-priced houses; at-large Council candidate Justin DeBerardinis proposes something similar, namely, restructuring the abatement so that its benefits flow more to lower-income homeowners and those rehabilitating older properties. As it stands now, only 28 percent of all abated properties have values of $250,000 or less. JLL found that extending the length of the abatement to 25 years for such properties — a proposal a bit more generous than one Domb floated when he headed the Greater Philadelphia Association of Realtors — would make it attractive to buyers and builders of lower-cost houses. This option and most of the capping options may also run afoul of the uniformity clause in the state Constitution and thus require action in Harrisburg to allow them to take effect.

Now that you know what the various options would cost, which one makes the most sense?

The best choice depends on what you want

The answer isn’t as obvious as it may seem, says Kevin Gillen, senior research fellow at Drexel University’s Lindy Center for Urban Innovation. “The report is something like a Rorschach test,” he says. “Wherever you are on the issue, you can find something in it that supports your argument.

“What your reaction is depends not on whether you’re pro- or anti-abatement but what your planning horizon is,” he continues. “If what you want is a quick infusion of money, yes, you can kill the abatement and get an immediate infusion of cash. But if you want to increase the tax base for the long run rather than increase taxes, then you want the less destructive options.”

Some of these options, however, may be difficult to implement. Especially the reforms that call for caps on the abatement or shifting its benefits downward. Such moves could run afoul of the uniformity clause in the state Constitution.

Gillen also pointed out that while the construction boom since 2000 has been torrid compared to what preceded it, it’s actually fairly anemic compared to what’s happened in other large American cities. “Our housing stock production has trailed cities similar to us in size,” says Gillen. “We’ve built 10,000 to 12,000 houses” since the current market cycle began around 2012, “but Dallas has built 50,000, and it’s smaller than us.”

And with housing affordability still a hot topic locally, keeping the abatement as is might be worthwhile for another reason: The report notes that almost all of the affordable housing developments built in the city in recent years took advantage of the abatements.