Who’s (Un)Building Philly: Greg Trainor

The founder of the Philadelphia Community Corps runs the ultimate adaptive reuse project: By harvesting the past, he's giving builders, students and those who've paid their debt to society the raw material for a future.

Greg Trainor | Photos: Sandy Smith

Attention local builders: There’s gold in that old house you’re about to demolish.

And Greg Trainor would like to help you mine it. The local youths and returning citizens who work in his job training program disguised as an architectural salvage shop would appreciate the effort as well.

For about a year and a half, Trainor has run the Philadelphia Community Corps out of a large warehouse on the edge of the city’s Juniata Park section. The warehouse is home to the corps’ retail side, Philly Reclaim, an architectural salvage shop crossed with a surplus store crossed with a flea market. Proceeds from the sale of items in the store also support the corps’ job training programs – salvaging the past to build the future, if you will.

A recycled recycling business

A guide for the perplexed inside Philly Reclaim. As the books and paintings behind the sign indicate, there’s more on offer here than building materials.

In fact, the very business is itself a recycling project. Trainor took it off the hands of Impact Services Corporation, a Kensington-based provider of social services, job training programs and community development services.

“They had a similar business called the Building Materials Exchange, where a lot of corporations would drop off materials that were either overaged or that they couldn’t sell to get a tax writeoff,” Trainor explains. Like Philly Reclaim, the BME then sold the donated merchandise to area residents in search of affordable materials for their own improvement projects.

“So they had a similar business here, but it wasn’t a good fit for Impact Services, so they ended up shutting it down. Then, when they met us and we said, ‘Hey, we’re doing this, and this is our whole focus,’ and we’re making it work and making it financially sustainable, they let us know that they had this space and they let us come in here and get set up.”

“This is what we do, we save things”

The raw material for Philly Reclaim comes from three primary sources: Buildings that are being demolished, overstock items that contractors and building-supply stores could neither use nor sell, and surplus building materials stockpiled by public-sector agencies and individuals.

And Philly Reclaim will sell just about anything that anyone brings to it. When I visited the store last fall, the available items included organ pipes that a donor had dropped off, deer skins, a phone booth, a pool table, and even old turntables and vintage vinyl LPs to play on them. There was wood reclaimed from a bowling alley, chalkboards from the old West Philadelphia High School, and a wooden bathtub filled with clawfoot feet for those needing them for their own historic restorations.

Golf clubs salvaged from an Impact Services athletic program.

And golf clubs. Loads of golf clubs.

“Another thing Impact did was, they had a golf program at one point which was taking kids from the city to country clubs to teach them golf,” Trainor says. “I don’t know how it came about originally, but they had tons and tons of golf clubs and they were about to throw them out. And we said, well, this is what we do, we save things.”

Some of the reclaimed and custom-made furniture on display at Philly Reclaim

A resource for the design trade too

“We keep things out of the dumpster and find treasures a home,” says Amy Laramore, the regular customer who now manages the Philly Reclaim retail store.

Amy Larramore

Larramore says that Philly Reclaim’s customers fall into four main categories: individual do-it-yourselfers who are looking for unique building materials and hardware for their projects, contractors working on remodeling projects, furniture makers who value the unusual woods the store frequently finds, and developers engaged in retrofitting historic properties.

In addition, the Philly Reclaim staff make their own furniture out of salvaged and surplus materials. Among the items on display in the “furniture showroom” section of the store on my visit were a farmhouse-style dining table and benches and a dog crate that doubled as a TV stand, all made from reclaimed materials.

“We have all sorts of things here,” Trainor says. “People drop things off and swap stuff here” – some regular patrons, he adds, treat the store as a warehouse of sorts, offering items for store credit that they then use to purchase other salvaged materials. “And we also have the crews going out, taking things apart and salvaging stuff.” Builders and demolition companies will call the PCC and invite them in to remove reusable or otherwise salvageable items.

City high school students also come to PCC to acquire on-the-job experience.

Dismantling the past to build a better future

Those deconstruction crews are themselves getting an education through another PCC operation, Philly Decon, which runs a six-month course that results in OSHA certification that’s needed for work on construction and demolition projects. Graduates also receive a deconstruction technician certificate from the Building Material Reuse Association.

The students enrolled in the PCC’s training program come from city public schools and the city’s prison system. It’s that latter group that Trainor is particularly concerned about.

From inmate to industry in six months

“The most important thing to keep them out of jail is that they have a job waiting for them,” he says. “And preferably, a job that is a career. I think there’s something special about working in the construction trades and developing a skill that you can [use to] move up in a career.

“And what I really love about the construction and demolition world for so many of these guys is that it doesn’t really give a damn about where you come from. It’s still a meritocracy in so many ways, in that you can come out of jail, you can be covered in tattoos, you can be any sort of person you want to be in your personal life, but what most people in the construction world really give a damn about is, Can you do the job? And how quickly and how well, and at what price? And we really don’t care about the rest.”

PCC gets the students for its training program from local community- and social-service organizations that set up partnerships with the corps. These usually come with grant funding that enables PCC to run the training for the partner organization.

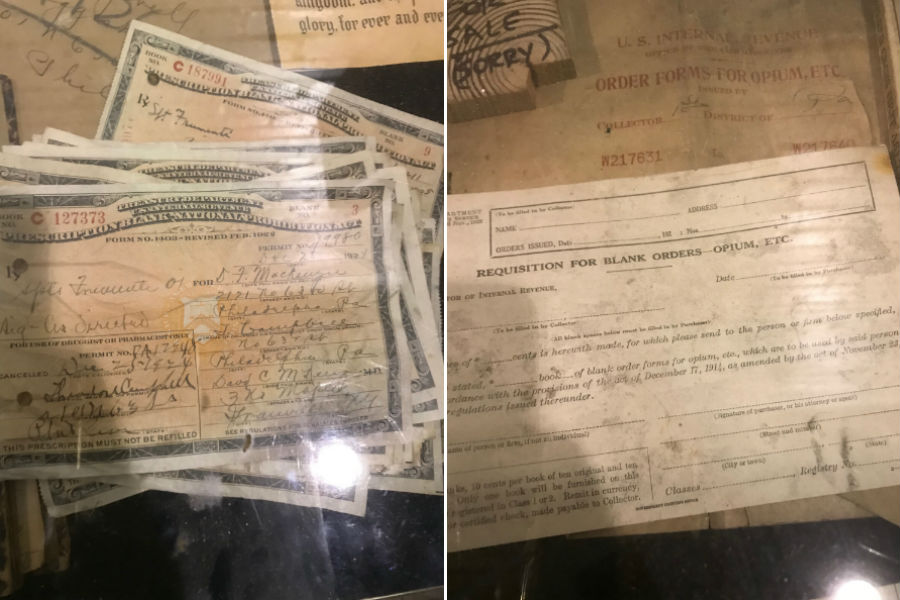

Among the other esoteric items available: a gun cleaning kit, above, and prescription forms for alcohol and requisition slips for opium required under the Volstead Act. Trainor noted the ironic parallels between Prohibition and the War on Drugs that has put many of the former inmates in PCC’s training programs in jail.

A triple bottom line and a virtuous cycle

What makes all this work is PCC’s nonprofit status. Trainor had explored the possibility of becoming a B corporation but ruled it out because he would not be able to offer donors tax credits for the materials they drop off. PCC also offers tax credits that donors don’t want or can’t use to builders with eligible projects through a complex but totally legal process.

All of this makes PCC and Philly Reclaim a triple-bottom-line operation. Builders and remodelers have a place where they can send their salvaged and surplus material in exchange for a benefit in the form of a tax credit that can be used to help make their own historic renovation projects profitable. Those same builders and remodelers also have a ready source of raw material they can use to get the authentic look for those projects. And members of the community get skills training they can use to launch themselves on the flight path to a rewarding career.

And Trainor has done no advertising to spread the word about the corps, its programs or Philly Reclaim. Instead, he’s relied on word of mouth from satisfied customers, community partners, and stories like this one.