How Passive Houses Yield Aggressive Savings

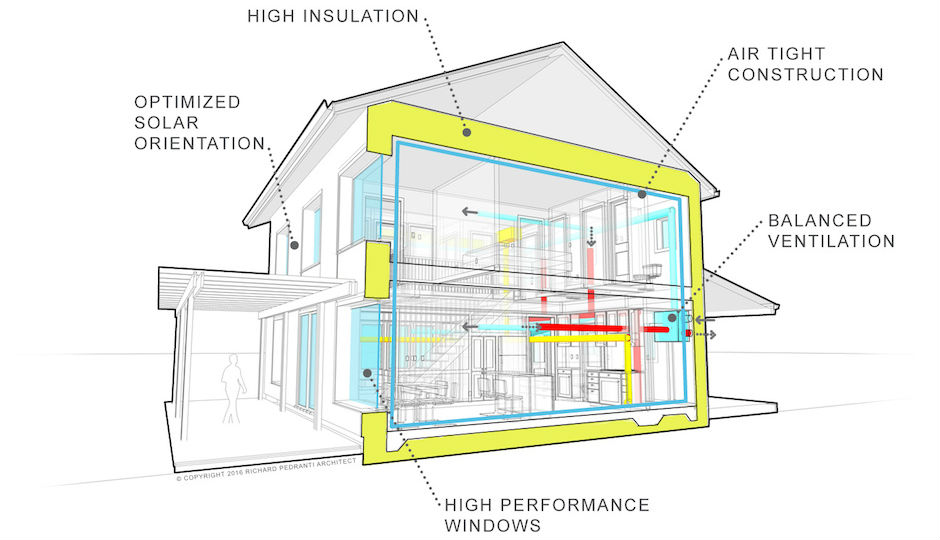

This cross-section shows the features that make passive house buildings super-efficient and extremely comfortable to live and work in. Energy savings of 80 to 90 percent are an added bonus. | Image: RPA

How do you keep warm in your home in the winter?

Do you crank the thermostat in the hall up past 78 so you can keep your bedroom at 68?

Do you stuff foam tubes under doors and tape plastic over drafty windows?

Do you take a space heater into a room that’s too cold?

Do you wrap yourself in thick sweaters and blankets?

If you do any of these things, you’re like more than half the country, according to a recent survey conducted by Ecocor, a manufacturer of high-performance sustainable houses and other buildings.

More than half of those surveyed said they struggle to feel comfortable at home during the winter months, and two-thirds said that their efforts to do so caused strife with spouses, other family members or roommates. Forty-three percent said that there are rooms they avoid or cannot use because they are too cold, and only 16 percent reported that they were “very comfortable” in their homes in the winter.

Pike County architect Richard Pedranti has a suggestion for how to fix all these problems: Instead of wrapping yourself in layers and stuffing things into cracks, wrap your house in layers and get rid of the cracks.

Pedranti is one of a handful of American builders and architects who champion “passive house” construction. “Passive house” buildings, which are becoming increasingly popular in Europe, are super-insulated, virtually airtight structures that rely on solar energy and the heat generated by people and appliances to do the heavy lifting on climate control, especially heating in the winter. A heat exchanger called a “heat recovery ventilator” (HRV) filters outside air and transfers heat to it from indoor air being exhausted. The result: a super-efficient home with healthier air and dramatically lower heating bills. (In the summer, the HRV simply reverses the heat transfer, sending the heat outside, thus lowering cooling costs.)

The layers that make this possible consist of extra-thick insulation and triple-pane windows that use solar gain to produce heat and keep it inside the building. Airtight construction is the “zipper” that closes the layers around the building.

The “Passive House” building standard was developed in Germany and can be used to construct buildings of any type.

“We’re 15 to 20 years behind what they’ve been doing in Europe to improve building quality,” Pedranti said. “Belgium has adopted passive house [building] standards nationwide, and several cities have adopted this approach as well. In Europe, 30,000 to 50,000 buildings, single-family, multifamily and commercial, have been built this way. In North America, we have 300 to 500 buildings built this way.”

Pedranti’s firm, RPA (Richard Pedranti Architect), is based in Milford but does work throughout a good chunk of the Delaware River basin, including as far south as Philadelphia and as far east as New York. Passive house technology is his specialty, and he has entered into a partnership with Ecocor to manufacture passive house components in a factory for assembly on a client’s site.

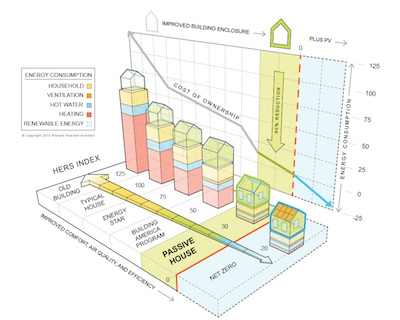

This chart shows how passive house construction dramatically lowers the total cost of ownership, primarily through heating cost savings of up to 90 percent. | Image: RPA

“There is no required manufactured system” for passive houses, he said. “You can use any manufacturer you want, and we can certainly build the house on site. But the better solution is prefabricating in a controlled factory environment.” By taking most of the labor involved in building a house into the factory, Pedranti and Ecocor can cut construction time and cost dramatically: “We can build a typical 2,000- to 3,000-square-foot house in five to seven days.”

Pedranti noted that passive house technology can also be applied to existing buildings and that using it would produce dramatic energy savings while increasing indoor comfort. “There are ways to do it, and it’s imperative to find ways to improve our existing housing stock,” he said. “Airtightness and insulation are the key.” Replacing older windows with triple-paned windows is the simpler part of the equation. The bigger challenge is figuring out where and how to add the insulation. “For instance, with a wood-clad building, we could take off the wood cladding, add the insulation and restore the cover. For a building clad in masonry or stone, we would put the insulation on the inside” by removing wallboard or plaster-and-lath walls, installing the insulation, then replacing the interior walls.

To date, the closest passive structure to Philadelphia Pedranti has built is in Berks County, but a few builders in Philadelphia have also built buildings that conform to passive house standards. Postgreen Homes, one of the city’s leading builders of sustainable housing, built a passive house in Fishtown that built on the lessons learned in its first project, the famed “$100K House”; a local architect was so impressed with the quality and efficiency of the design that he purchased the home for his residence. One of Postgreen’s current projects, Arbor House in Fishtown, incorporates passive house elements, including triple-pane windows with twice the efficiency of Energy Star-rated windows.

Postgreen Marketing Manager Ethan Peck said that instead of pursuing passive house certification, however, Arbor House will be built to the LEED Platinum standard, which places a high value on energy efficiency but also takes other considerations into account. “Often, passive houses will be more energy efficient than LEED houses, but LEED usually makes up for that in other areas,” said Peck. “They aren’t mutually exclusive.”

New passive houses typically cost 10 percent more to build than houses built to current local building codes, but when one factors in energy savings of 80 to 90 percent over the lifetime of the mortgage, passive houses turn out to be cheaper than conventionally built ones, according to Pedranti.

Postgreen is a member of the nascent Greater Philadelphia Passive House Association. The Passive House Institute US is the national resource for those interested in learning more about passive house construction. The RPA website also offers a detailed explanation of how passive house technology works and the benefits it offers to homeowners and building developers.