A Celebration of the Woodwards, The Family That Made Chestnut Hill

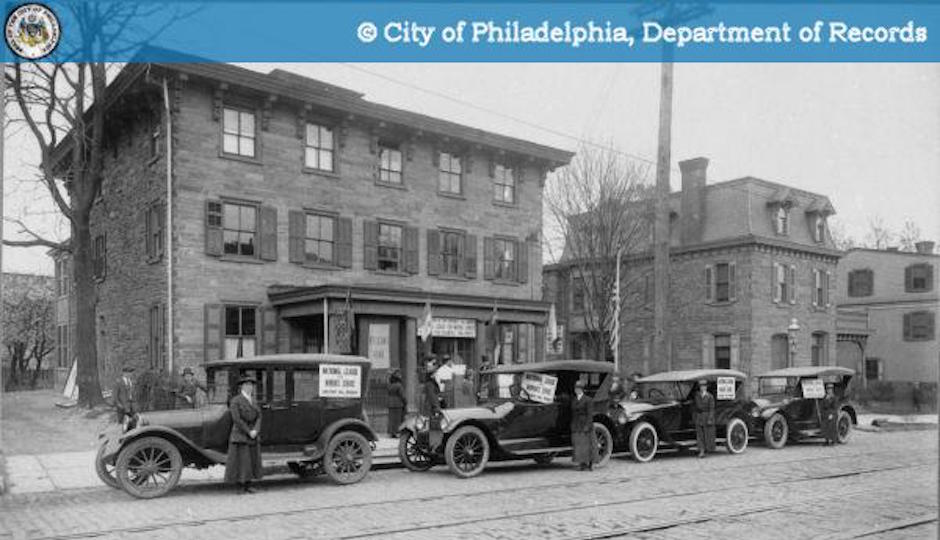

The Chestnut Hill Community Centre in 1918. | Photo courtesy PhillyHistory.org, a project of the Philadelphia Department of Records

This year marks the 100th anniversary of Chestnut Hill’s “town hall,” the Chestnut Hill Community Centre. To mark the occasion, ensure the building lasts another century, and honor the family that gave it to the community, Chestnut Hillers gathered at Chestnut Hill College the evening of June 9 to honor the role the Woodward family has played in the shaping of Chestnut Hill.

And Charleston.

Elizabeth Woodward, who married George Woodward’s son Charles, hailed from the South Carolina port city and got the family involved in the preservation of its history and improvement of its public realm. The attendees at last night’s gala dinner for the Woodward Celebration heard ten-term Charleston Mayor Joe Riley describe the “scheme” by which the family enabled the city to build a prize-winning waterfront park two years ago.

But that’s a tangent to this story. The legacy being celebrated in Chestnut Hill is one of stewardship and social conscience, construction and charity, and above all concern for the qualities that made Chestnut Hill a standout neighborhood.

That legacy begins with Henry Howard Houston, the Pennsylvania Railroad freight executive who oversaw construction of the Philadelphia, Germantown and Chestnut Hill Railroad, a branch off the Pennsy’s Connecting Railway, in the 1880s. Around that same time, Houston developed Wissahickon Heights, the first of several planned residential communities on the west side of Chestnut Hill. After Houston died in 1895, much of the land he controlled eventually passed into the hands of his daughter Gertrude, who had married physician George Woodward the year before her father’s death.

That marriage turned Woodward from doctor to real estate developer. Together, the Woodwards built several more developments in and around Chestnut Hill, including French Village, Cotswold and Old English Village.

“They would take trips to France and England and come back with ideas,” said George’s grandson Stanley Woodward, president of the George Woodward Company. “They would then use the best Philadelphia architects to design houses based on those ideas.”

The Woodwards built houses in a wide range of configurations: single-family detached, twins and quads, a radical design that consisted of two back-to-back twins. The idea, Woodward explained, was to produce houses at a wide range of price points so that everyone from stonecarvers to shopkeepers to teachers to doctors could live together in Chestnut Hill. “It was a mixed group that made a complete village,” Stanley said. “They wanted diversity in all kinds of income brackets. It was a healthier way of living,” said his cousin, George Woodward III, who runs the separate but related Woodward House Corporation. “Chestnut Hill was never intended to be a Greenwich, Conn., or a Palm Beach.”

While the Woodward House Corporation now focuses on preserving the homes it manages, the George Woodward Company has resumed the family practice of building houses with an eye towards the health of the community. These twin homes on Springfield Avenue, built in 2009, were the first twin homes in Pennsylvania to earn LEED Platinum certification. | Photo: Courtesy George Woodward Company

From roughly 1911 to 1936, the Woodwards built some 400 houses in Chestnut Hill and neighboring Mt. Airy. Unlike most developers who subdivide land into parcels and sell both the land and the homes to individual buyers, the Woodwards retained ownership of the land beneath their developments, giving them a high degree of control over their condition and appearance. A good chunk of that land remains in Woodward hands today. The George Woodward Company owns about 120 of those houses along with a handful of apartment buildings; the Woodward House Corporation was spun off in 1970 and controls a similar number, with the rest being sold in the years following George’s death in the 1950s.

Both companies remain committed to housing diversity and keeping rents reasonable. George III said, “You will see that we offer about the lowest rent in the country” for housing of its caliber.

A concern for the welfare of both their tenants and the larger community also underlies the charitable and community service activities the Woodwards have engaged in over the years. George’s activities included sponsoring a mission for homeless men and running the Octavia Hill Association, an organization still in existence that provides housing for working poor families. Today, in a form of enlightened self-interest, the George Woodward Company provides significant support to the Jencks School, the neighborhood’s public school. “We find that for our tenants with limited income, public education is crucial, and when we have good tenants, we want to keep them,” Stanley said.

Gertrude Houston Woodward donated the building that houses the Chestnut Hill Community Centre to the Chestnut Hill Women’s Exchange in 1916; when its successor nonprofit closed up shop last September, ownership passed to the Chestnut Hill Community Fund, a nonprofit affiliated with the Chestnut Hill Community Association. The Woodward Celebration has as one of its aims raising the money needed to repair and maintain the Community Centre. “We’re refashioning it into a place where people can come together, a true center of the community,” said George III.

Its other aim is to introduce a new generation to the Woodwards and their role as both shapers of Chestnut Hill and civic-minded Philadelphians. On Saturday, June 11, at 12:30 p.m, the community center will be renamed in honor of Gertrude Woodward in a ceremony on Germantown Avenue, followed by a community picnic. The celebration concludes on Sunday with a worship service at St. Martin-in-the-Fields, the Episcopal church Houston built.

Follow Sandy Smith on Twitter.