Gentrification in Philadelphia

The DN’s special section appears in today’s print edition as well as online.

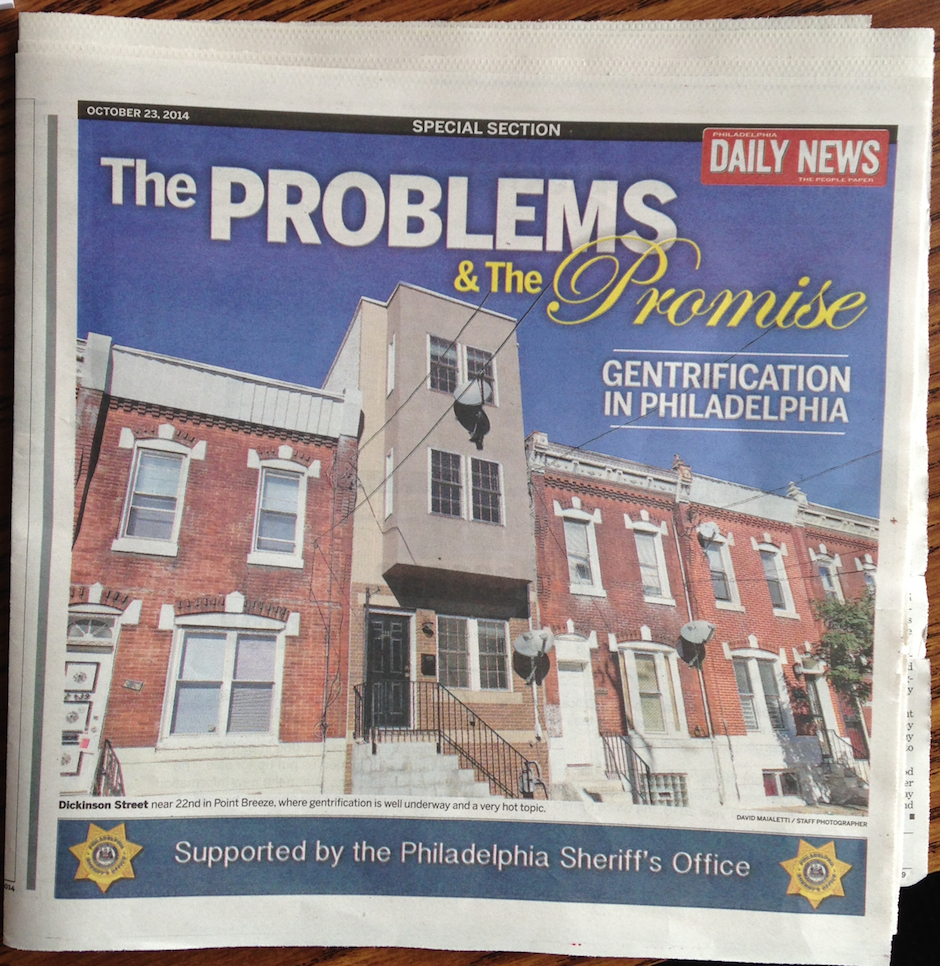

For those who think daily newspapers lack a purpose in a digitized world that threatens to make traditional media outlets obsolete, today’s coverage of gentrification in a Daily News special section is a firm rejoinder. The seven articles that comprise “The Problems and the Promise: Gentrification in Philadelphia” is a pull-out section of the print edition and a microsite at philly.com. It illuminates the issues around the word that’s probably the most contested and least understood of any used to refer to real estate and development battles in the city.

The project isn’t perfect. There are missteps — like the boldfaced use of the term “Templetown.” But there are important myths that get debunked, and crucial facts that must be called to every Philadelphian’s attention before they expound on gentrification. Because, oh boy, do people expound. I hear far too much strident talk about “gentrification” from people ill-equipped to understand it. This series should help.

The key takeaway is that gentrification isn’t necessarily what you think. Gentrification, writes Earni Young, is “the change of a block or neighborhood from low value to high value.” It’s “a natural phenomena that has been with us since Benjamin Franklin,” Temple professor Carolyn Adams tells Young, who notes that “Kensington and Fishtown, for example, were traditionally blue collar white neighborhoods. And in San Francisco white middle class professionals are being shoved aside by higher income earners in the tech industry.” Of course, San Francisco is overwhelmingly white.

Philadelphia is the 9th most racially segregated metro area in America. That makes gentrification here seem inextricably linked to race. The actual inextricable link is class, and that’s tough in this town too, because, as Young writes, Philadelphia is “one of the poorest U.S. cities, with 26.9 percent of residents deemed poor by federal standards.”

But gentrification isn’t taking its toll on homeowners who live below the poverty line.

[T]he economic pressures created by rising home values and higher taxes feed the fears that longtime homeowners will be forced to sell because they can no longer afford to stay.

But Adams says there is little direct displacement due to gentrification.

“When housing specialists use that term, they really aren’t talking about displacing people,” she said. “They are talking about market pricing that makes it impossible for people who are looking to move into that neighborhood who cannot find an affordable unit. That really is more the dynamic of gentrification now.”

My guess is that Adams is referring primarily to homeowners here. The story is quite different for renters, especially those who rely on public assistance. Higher rents, more than anything, seems to be what changes a neighborhood’s population and identity. Take this example from Graduate Hospital:

Jerome Whack, the owner and operator of the 20th and Christian Street Pharmacy for 45 years, said his customers complain daily about the disappearance of affordable apartments in the area. They tell him of rent hikes they can’t afford, landlords no longer willing to accept their federal rent vouchers, and of new owners who want them out.

The new renters are willing to pay $1,300 and up for renovated digs in old brownstones just a few blocks from trendy shops on Walnut Street and the entertainment venues that line South Broad Street.

And here’s where class butts up against race again: the majority of those who can pay such rents in Southwest Center City are white.

The special project also has some fine maps, including one with the top 10 vs. bottom 10 changes in average house rents by neighborhood. In Cedar Park, where I used to live, rents have gone up 60 percent in the last four years. Because I could no longer afford my apartment, I recently moved to Mt. Airy, which is one of the bottom 10. There, rents have increased only by 6 percent. I watched the process of gentrification happen in Cedar Park; I probably contributed to it. Mt. Airy is very unlikely to gentrify, as economist Kevin Gillen told the DN’s Wendy Ruderman:

“The whole gentrification issue is really the story of the outward spread of Center City. The rest of the city is still stuck in the 1970s. I would say proximity and accessibility to Center City is not just the primary thing driving gentrification in Philadelphia, it’s the only thing. The main thing that is driving it is how quickly and easily you can get to Center City, because that’s where the good-paying jobs are.”

Mt. Airy, he said, “is a nice area, but you have to drive or it’s a 30-minute train ride into Center City.”

One notable Mt. Airy resident had this to say to Earni Young about gentrification:

“Gentrification is a very charged word that means a lot of different things to different people” said Alan Greenberger, deputy mayor for economic development and director of commerce. “At their core, cities are organic and they change over time. That is a very hard process to get in the way of. If someone offers you money to buy your home for much more than you ever thought it would be worth, you have a right to sell it. You also have the right to stay put.”

READ THE SPECIAL PROJECT HERE. (That’s a command, by the way.)