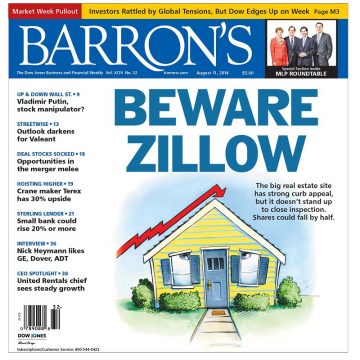

Zillow + Trulia = Godzulia?

The cover that has people talking.

The cover alone has been making waves, but it’s the inside headline that really has people talking: “Zillow Shares Could Fall By Half.” When Barron’s speaks, investors listen, so this cover story is probably not what Zillow CEO Spencer Rascoff wants to see just weeks after announcing a merger with former rival Trulia.com. Until now, it’s been a good year for Zillow on Wall Street, with shares rising about 70 percent, according to Barron’s writer Bill Alpert. Trulia’s shares went up in the wake of the merger announcement too. And until now, market watchers have been optimistic. Perhaps too much so, Alpert says:

Bulls have dubbed the planned combination Godzulia, imagining that the two sites will grab a big piece of the $10 billion that realtors spend annually on advertising…Godzulia, however, may not be as awesome as feared. Neither company is expected to make a profit this year under generally accepted accounting principles, or GAAP, nor produce much free cash flow.

Not only that, but Barron’s says both sites have the same problem every other content-based website does: an inability to turn high traffic numbers into dollars:

Though the market capitalization of both companies almost equals the marketing budget for all U.S. realtors, the pair haven’t monetized much of their Web traffic: They get just a sliver of real estate advertising dollars. Realtors say that’s because the Websites draw far more lookers than buyers. While mergers-and-acquisitions enthusiasts imagine a combined Zillow-Trulia as an advertising “must buy,” both have been quietly offering deep advertising discounts to real estate chains such as Realogy Holdings (RLGY), discrediting the thesis that the sites have any kind of pricing power.

Yet the bottom line is that Zillow has more than 50 million monthly visitors, which is why Rascoff — if not investors — are optimistic. “We have the audience,” Rascoff tells Barron’s. “Eventually, the advertising dollars will follow the audience.”

Here’s the basic outline of how Zillow works right now:

The business model for both companies is to attract as many viewers as they can to their portals, which they fill with pictures, maps, data, and consumer reviews. A tele-sales force then tries to cash in on those visitors by selling ads to real estate agents and other professionals involved with the sale or rental of homes. Next to each home’s picture, the sites post links to several “premier agents” who have bought a certain number of advertising impressions in a particular Zip Code. The seller’s agent who actually originated the listing gets exiled to the bottom of Zillow’s Web page (as shown on the facing page), unless he or she also paid to advertise — or paid Zillow to block the posting of competitors’ ads.

The Websites spend heavily on marketing to both potential home buyers and agents, such that about half of Zillow and Trulia revenues in the past 12 months have been eaten up by those expenses. In Zillow’s June quarter, selling expense topped 61% of revenues — including those higher-than-projected sales commissions.

This model has generated plenty of animus between Zillow and brokers, which Alpert touches upon. Basically, the narrative from the realtor end of things goes like this: The industry tried the online stuff, it didn’t work, now Zillow wants to eat our dinner while we’re out at all hours, answering four different cell phones and driving clients around to multiple properties.

Alpert quotes an agent in Memphis who blithely says, “We don’t need them now. This is a strong real estate market. I can turn around and bump into a buyer.” Isn’t that lucky? I wish her the best in her turning, but I suspect she may get dizzy.

There are no guarantees, as we learned from 2008. I think most agents know they do need Zillow and Trulia, generally speaking, but it depends on a variety of factors: the market, the property, the price point, the intended buyer. In fact, Alpert writes:

The majority of large brokerage chains, and many agents, are happy to spend some of their ad budgets at Websites like Zillow. “The consumers have spoken,” says Mike Ryan, an executive vice president at the Denver headquarters of Re/Max Holdings (RMAX). “You have tens of millions of consumers going to these sites to preview properties and get information.”

“We see them as marketing partners,” says Mark Panus, a spokesman for Realogy, the residential real estate giant whose brands include Coldwell Banker and Century 21.

Big chains like Realogy, Long & Foster, and Weichert have built out divisions to take in leads from portals like Zillow, Google, and the brokers’ own Websites. The Internet leads get scrubbed, then sent to the brokers’ local agents. Weichert buys ads on about 350 different Websites, says Montsko, who is president of the firm’s “lead network.”

(I’m getting a 21st-century Glengarry Glen Ross feeling from that paragraph.)

Ultimately, the question for Godzulia will be the same question for every other Internet-based service that either purports to take the place of a bricks-and-mortar business model or tries to offer supplementary service to a given industry: Will visitors to the website do anything? “The Internet may be swallowing up industries like travel, where airline seats or hotel rooms are commodities and the consequences of a bad choice are modest. But consumers still seem to think home-buying is a big deal.” People aren’t buying homes online. They’re just not. But they sure are looking, and in my opinion, realtors would be incredibly short-sighted — and behind the curve — to ignore that fact.

Zillow Shares Could Fall By Half [Barron’s]