Todd Carmichael Is Stepping Down as La Colombe’s CEO to Reinvent the Way You Drink Water

Todd Carmichael wants to transform our taste buds all over again, one bubble at a time. Photograph by Dave Moser

During our first conversation, Todd Carmichael took me to Bolivia, Monte Carlo, Antarctica, Haiti, Death Valley and Fishtown, and those weren’t even the most interesting parts. In the first 15 minutes of our next conversation, I learned it was possible to drink a pillow. The most interesting parts? We’ll get to those.

If for some reason you’re unfamiliar with the name, Carmichael has been a Philly fixture since 1994, when he and his business partner, J.P. Iberti, founded La Colombe and brought high-concept European-style coffee to the city. La Colombe would grow not just as a chain of cafes here in town and other major cities, but as a coffee wholesaler for restaurants across the country. Later, Carmichael would create and figure out how to mass-produce a gas-infused canned latte that captured the mouthfeel of fresh foam and revolutionized the beverage industry. He became a celebrity along the way — a world record-holder, an endurance adventurer, star of a Travel Channel show. In 2005, he married singer and TV host Lauren Hart, and they later adopted four children from Ethiopia. (They grow up so fast — those kids are ages 10 to 19 today.)

Todd Carmichael with his wife, singer-songwriter Lauren Hart, and children. Photograph by Colin Lenton

None of those things were in the original plan except for the coffee.

That’s why it sounds shocking to say: Todd Carmichael is leaving the CEO position at La Colombe and turning his attention to more than just coffee.

The first thing to understand is what Todd Carmichael is not leaving: He still has a role at La Colombe, though the lion’s share of his attention is now devoted to his new venture. More importantly, he is not leaving Philadelphia and his entrepreneurial roots. In fact, he’s doubling down on both by launching a new bottled-drink business called Rebel Beverage Labs, right here in the Delaware Valley. And as with his coffee mission, Carmichael wants to change everything we know about sparkling water.

As someone who’s gotten a behind-the-scenes taste of what he’s bottling, I can say objectively: Holy crap. I’m no beverage insider, nor am I an industry expert who can predict just how much of this new stuff he’ll sell.

But I can say holy crap. And you probably will, too.

Fun fact: Researchers in cognitive function and human nature have found our goofy little brains to be naturally wired to seek out the easiest way forward in any situation. That makes “the path of least resistance” an official research term rather than just a cliché. We weigh what scientists call the “cost to act” — what it will take to achieve a desired outcome — and we tend to pursue the lowest cost to act every time.

If there’s a guy out there who always chooses the path of most resistance, it might be Carmichael.

He knows it, and at age 58, he doesn’t argue with what’s worked his whole life. He has almost always taken “the hardest road possible.” Why? The reason isn’t as crazy or contrarian as you think: Carmichael was once a foster child and was raised with three sisters by a single mother in Washington state, so there was never a lot of money. Even as a kid, he recognized that if he took the hard road in any decision, he wouldn’t be competing with as many people.

“When it came time in high school to choose a sport, I chose cross-country and track distance. That was not where everybody wanted to be,” he says. “That got me into the University of Washington on scholarship. When I got there, I looked around and thought, okay, I’m going into tax law, because that’s the one that had, like, six people in the graduating class.”

He became one of those select few UW accounting tax-law grads and landed a job at Ernst & Whinney. That’s when he learned another lesson — and today, it may be more a part of his psychological wiring than a lesson: Once he achieves something he wants, his perception of the thing itself changes in a fundamental way.

“I loved the studying of tax law because it was so hard,” he says. “But I didn’t like the practice of it because it was so painful and mundane.” Which surprises no one who isn’t in accounting, of course, but just like that, Carmichael reveals a core motivation: “And so unimportant. I was just, like, There’s no significance in this. I looked around those offices, and I didn’t see one person I wanted to be like. I thought, Who would be that person I would emulate? Who would be my hero here? There was not a single hero in that game. So I just jacked it.”

Heroism, having someone to look up to, mattered to him and still does. “This is a very basic idea that I got from movies,” he says. “I see this whole movie theater filled with people who admire the hero on the screen, but no one is willing to live that way. I just made that simple leap: You have to be your own hero. You’re it, Todd, because no one’s going to step up.”

He had no father to impress (and recognizes the role this might play), so a dominating thought owned his brain: Impress yourself.

“So I did,” he says.

This hero’s journey began on a Monday in 1989 when he quit his job as a tax consultant. By Saturday, he was in France. He had a plan in place. Washington state wasn’t exactly short on these new cafes called Starbucks, and both he and Iberti worked for the company for a time. They thought a coffee business would do well if done in a new way. “We talked about it forever,” Carmichael says.

He’d stashed some cash from his tax work and figured he’d need to raise $100,000 to start their venture. He spent the next three and a half years in Europe, working just about any kind of job he could find: some tax business, yes, but also rebuilding boats, engine work, welding, competitive sailing and more. He bought an old sailboat and refurbished it himself while living on next to nothing. (“It was about the same price as living in a van, but cooler.”)

Todd Carmichael and J.P. Iberti in 2018. Photograph by Alexander Mansour

He also found ways to learn as much about the coffee business as he could. “European coffee kicked the shit out of anything in the United States,” he explains. “So I just indentured myself to a couple of roasters and learned the methodology and thinking behind heat roasting, profiling, and just really took my coffee game to a whole new level.” After years of European adventuring and learning and drinking coffee, Carmichael had stashed $109,000. He sold the boat and told Iberti to get ready: “I’m going to bring not only this European idea of coffee, but I’m going to Americanize it by jacking it up even higher. I wanted to do an exaggerated form of what they’re doing in Europe. That was the beginning of La Colombe.”

And thus, in 1994, Carmichael and Iberti entered the fair city of Philadelphia. The destination wasn’t random. They could have picked New York or Los Angeles or even gone back to Seattle or Spokane. The mid-’90s would see the emergence of Starbucks as the force we know it as today, but Carmichael refers to that company’s product as “coffee 2.0.” He was interested in serving the 3.0 or 4.0 versions. The way he saw it, he and Iberti needed Philly as much as Philly needed them, even if Philly didn’t know it yet.

“There were no cafes in Philly,” he says. “I wanted a city that needed me back. We grew together, and I’ve said it a million times: There would be no La Colombe or Todd Carmichael without Philly. Philly requires you to be raw and real. You’ve got this daily reminder to stay on the ground, and you respond to what is around you in a real way. And I liked that about Philly. It’s like having a big brother on your shoulder all the time, saying, ‘Watch it. What are you doing?’ Other cities don’t tether you like that.”

The ’90s — and the years leading up to the present day — were also a time of extreme evolution in American specialty foods and beverages. Up until then, when you considered American coffee, or bread, wine, cheese, beer, even seasonings and sauces, our country was pretty much known for the watered-down Sanka versions of each. No corporate thinking included things like flavor or mouthfeel. European versions of all those products had always been considered superior. Not now. Today, versions 3.0, 4.0 and beyond are everywhere.

“Europe had been working on this for a thousand years, and we caught up in 30,” Carmichael says.

Aside from serving and supplying some of the greatest coffees in the world and transforming how that coffee is sourced, La Colombe’s capstone may be its canned draft latte. That goes back to Carmichael’s default setting of Change everything. How do you get the taste and mouthfeel of fresh latte out of a can?

“It always begins in the imagination,” he says. “That’s a hard thing to explain, because you’re looking for something that’s missing. If your brain sees what exists, it can figure out how to make that better, for sure. But to find a missing something is always very hard. Can you go into the grocery store and see the spot on the shelf where something new belongs?”

He created the first latte prototype in three days. Then came the bigger question: “How do I make 600 of these a minute? So you’re back to your imagination.”

“If your brain sees what exists, it can figure out how to make that better, for sure. But to find a missing something is always very hard. Can you go into the grocery store and see the spot on the shelf where something new belongs?”

He and his team figured out the logistics, obviously, and the canned beverages transformed the business. And, in fact, kept the lights on during the pandemic, when brick-and-mortar cafes and bars everywhere were kicked in the soft place.

And now? After all that work and evolution and transformation and success and becoming a kind of Philly royalty himself?

Todd Carmichael is switching from coffee to sparkling water.

The first question when one hears such news is: Why?

Rumors run rampant when any big shakeup happens. Carmichael is happy to give his explanation for why he’s leaving La Colombe’s top job. But to really get it, you must first travel with him to Antarctica.

For all his Philly coffee-business adventures, Carmichael is also known for his other exploits, whether that’s trotting the globe looking for coffee for Dangerous Grounds, his Travel Channel show that ran from 2012 to 2014, or submerging himself in various African cultures, or setting off on foot through the Haitian backcountry to find that one treasured coffee bean. Carmichael has ultramarathoned on foot and done the ocean equivalent in a sailboat, but one of his most obsessive goals was to trek 700 miles from the coast of Antarctica to the South Pole “and not die.”

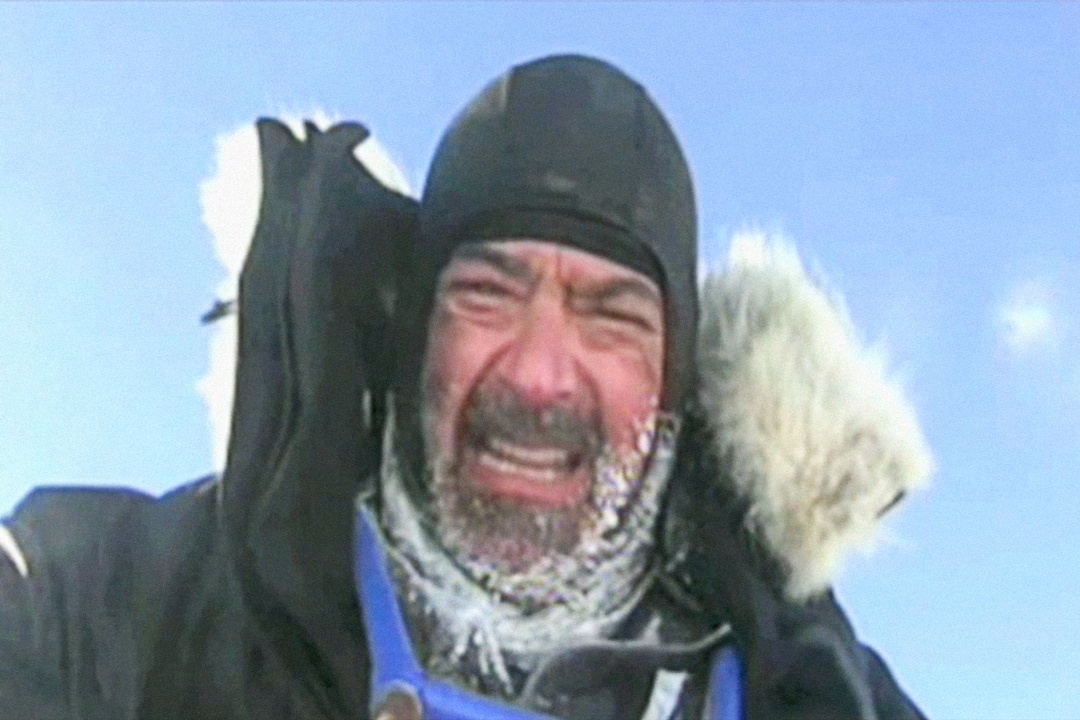

Not only did he succeed in 2008; he set a world record: 39 days, seven hours, 49 minutes. (It’s tattooed on his right arm.) He’s told the story many times, and it involves breaking his skis eight miles into the trip and doing the final 692 miles in ski boots, uphill the whole way to 14,000 feet above sea level, working through 40-to-60-knot winds in 60-below temps, pulling a supply sleigh that started at 275 pounds, and racing against a severe body clock. “You’re eating 9,000 calories a day, but you’re burning 12,000,” he says. “So your body is getting smaller and smaller by the minute. And there comes a point where your body can’t heat itself if it’s too thin. So you gotta get there before that happens.”

And he did. He touched the South Pole. As in the literal pole, which — no joke — looks like a barber pole with a crystal ball on top.

Todd Carmichael at the South Pole.

Now think back to what Carmichael learned previously: Once he achieves something he wants, the thing itself changes in a fundamental way. That feeling was never more intense than after he tapped that pole.

“When you get the goal, it’s the most depressing thing that ever happens to you,” he says. “I killed it. I literally cried because I killed it. I lived with this work and the dream for four years, it was a beautiful four years, and it was over. When you have an unmet goal, you have something. Let’s go into a waiting room at the dentist. You may have the magazines to read, but I have some beautiful thing to think about, this little life running in my brain. You’ll never get bored. Even when you’re sitting motionless, even when you’re driving to Toronto and your kid’s snoring in the back seat, you’re stoked because you can think about your dream. It gives your life so much meaning.”

Then he chuckles. “But when you touch the pole, it just goes away.”

He was in a literal state of grief while recovering at the main South Pole science facility. That is, until he was on the cargo carrier on the way back home and halfway over the southern seas had an epiphany: Set a record in the coldest place, set one in the hottest place. Two words turned his frown upside down: Death Valley.

That’s Carmichael’s brain in a nutshell.

J.P. Iberti and Carmichael have been best friends since the ’80s and business partners for nearly 30 years. “If you use a mountain-climbing analogy, we’re basically perfect climbing partners,” Iberti says. That streak will continue, as Iberti has joined his friend’s new venture, concurrent with what they both call an amicable transition within the company they started.

Years ago, as La Colombe grew, the co-founders linked up with some big money from private equity firm Goode Partners. They also became friendly with Hamdi Ulukaya, the CEO of Chobani, when the exec appeared on an episode of Dangerous Grounds. Ulukaya eventually bought out Goode Partners in 2015 and became the majority owner of La Colombe.

Today, Carmichael and Iberti are no longer involved in the day-to-day operations at La Colombe, with Iberti taking a reduced role in the cafe side of the biz and Carmichael working on innovation and quality. Ulukaya remains, as chairman of the board. According to the two co-founders, the company is a mature one that needs executives to run it, not innovators. “You could almost say we were in the way,” says Iberti. “It was just time.”

For Carmichael, it boils down to this: With regards to La Colombe, he’d tapped the pole a long time ago and hadn’t accepted it. “I’m still involved,” he says. “But I’m finished being the CEO of that company, because I don’t want to be an administrator anymore. I want to take my ideas and climb again. I want to create again.”

He’s been experiencing a period of mourning similar to the one in Antarctica. “I know this is the right thing,” he tells me. “I just don’t like the feeling it gives me. You can’t spend 28 years giving every single atom to that place and then feel like, ‘Oh, that’s good. I’m moving on.’ No, no, no. I can even say a year ago I wasn’t capable of it, until COVID.”

Yeah, that.

The pandemic brought tragedy to many people, and for Carmichael, it was a one-two punch. First, the virus took his mother: “It’s like the music stopped. The carousel. The whole world went quiet.” Then, right before Christmas last year, he was infected. It was bad — not hospitalization-bad, but enough that he thought his life was in danger. He quarantined in his home office for the duration and had nothing but time to feel like crap and think. And he thought: I’m 57. I still have bullets left. La Colombe will be fine without its founders, and I’m simply not doing what I was born to do anymore.

Being CEO, he says, was “like living in a frosting dream — everything’s sweet and lovely. Everyone thinks you’re funny and your ideas are brilliant. It’s so artificially weird, but it’s very addictive. I realized I was drinking from that. And I went, I gotta stop. This is not what we came here for.”

He remembers emerging from his study on Christmas Day — day 11 of his illness — and watching the kids open their gifts. “It was like, This guy’s gonna make it, you know? And by New Year’s Day, I knew what I was going to do. I’m going to live my real life.”

To find Carmichael’s new facility, Rebel Beverage Labs, I had to travel into the middle of nowhere in the middle of everything. The Schuylkill River is a useful landmark, and you’d recognize some nearby route numbers, but you won’t find this place unless you know where you’re going. RBL itself is just a medium-size unit in an industrial park. No signage. No Wonka-esque veil of mystique or gatekeeping. It’s a world of pure imagination, however, because at the time of my visit this past August, the joint was mostly empty. RBL was truly in its infancy, and I had to picture what it will become.

The physical layout has three layers. First, a carpeted office and reception area, mostly unfurnished except for a coffee table and some chairs as well as a trophy case against the far wall. The second layer is Carmichael’s lab. It’s a medium-size room and doesn’t look much different from any industrial workspace. The only clues to what he’s doing there are a bunch of clear plastic bottles waiting to be filled and the centerpiece of the lab, a machine he built himself: a four-nozzle bottling station that allows him to experiment with whatever crosses his mind, water-wise. The machine looks like a really hard-core soft-serve ice-cream dispenser.

The third layer is the production area in the rear, a few thousand square feet of concrete floor with a high ceiling. Again, mostly empty except for a true jalopy of a bottling machine that he “had to have” when he saw it. He’ll retrofit it for RBL’s four needs: rinse the bottle, fill the bottle, dose it with whatever ingredients are needed, cap the bottle.

Todd Carmichael, pictured here at Rebel Beverage Labs. Photograph by Dave Moser

In that regard, the tour is short. But it brings to light a bigger element of the tale that’s been neglected so far. Yes, there are the big dreams in the waiting room. But the more you talk to Carmichael and examine what he’s accomplished, the more this story becomes all about the physical. The hands. The sweat. The building of cool things, be they engines or roasters or old sailboats or the right rickshaw to haul his supplies during a Death Valley trek. The getting underneath something and bending metal, turning bolts, making stuff fit. Carmichael classifies himself as a binger. He casually mentions a time when he was 14 and his mother found him at 3 a.m. passed out on the engine block of a ’41 Chevy pickup he was obsessively rebuilding. The old engineer joke goes, “The glass isn’t half empty or half full. You’re using the wrong glass.” That’s what this is about.

For a while, it was about the right roast of the right bean. Then it was about the right roast of the right bean with the right dose of nitrous oxide in an aluminum can.

Now, it’s about the bubbles.

Time for the highlight of the tour: the tasting.

We sit down in his reception area, and he places two plastic bottles in front of me. One is a bottle of lime-flavored Perrier. The other is a clear plastic bottle, no label.

Let’s preface this with Carmichael’s stated goal. Water, as it exists now, has two mouthfeels: still, and sparkling. “I think there should be a third mouthfeel,” he says. “In fact, someone should make mouthfeels three, four and five.”

That may sound simple on the surface, but when you taste what he’s created … well, Carmichael explains to me how it all works. You don’t give much thought to the ingredient label of your average seltzer when it says “carbonated water and natural flavors” and nothing else. That means you don’t give much thought to what it takes to create that carbonated water.

“Carbonation is so easy, they were able to do it in 1807,” he says. What’s not easy is doing it differently from the way it’s always been done, especially when you consider the popularity of today’s best-selling bubble drinks, from seltzer to Mountain Dew to champagne. Apparently, there are many ways to manipulate gases and the character of the water to play with that carbonation. That’s what Carmichael is up to in his lab with his homemade gear.

“The first characteristic of carbonated water’s mouthfeel is a really big bubble,” he says. “Now, we all know within the carbonated space that the smaller the bubble, the better. Like champagne. Smaller bubbles change the mouthfeel. So you say, ‘All right, I want to make a bubble 10 times smaller.’”

Another mouthfeel characteristic: “Sparkling water has this bite. When you combine CO2 and H2O, it creates carbonic acid that burns your mouth and throat. So you go, ‘Okay, what’s the opposite of burn?’” Carmichael smiles and says, “Sweet.”

I taste the Perrier first. Standard-issue, whether you’re talking La Croix or the Giant store brand. Then I taste his mystery water side by side with the French stuff. Yeah, I actually say, “Holy crap.”

He’s created sparkling water that’s sweet without adding a grain of sugar or artificial sweetener. The only additive to this sample is a bit of grapefruit essence. And it delivers the opposite of bite. The stuff feels soft in your mouth. The bubbles feel like gentle Pop Rocks. I’m no master of palate, but the word I’d use to describe the mouthfeel of this water is … pillowy. Yeah, pillowy.

Carmichael’s description is similar: “Like sipping from a cloud.” He’s played with the bubbles, lowered the acidity, and totally transformed how sparkling water feels and tastes when you drink it.

The sample I taste is tentatively named Fat Daddy because it was created with input from Carmichael’s children: “They wanted something that was big-bubbled, fluffy, no burn, no bite, but really sweet like Dad, right? So Fat Daddy. I like nano bubbles that pop slightly in the back of the mouth.”

This is what Rebel Beverage Labs is all about. Not just creating groundbreaking new drinks, but creating the technology that makes creating those drinks possible. That goes back to the physical building of machines to pull it off.

Step one: “You go, all right, how do I create that beverage?” Carmichael says. “You start moving all the pieces in your mind around until you go, That might work. And you get all the pieces in your lab or down in your basement next to all the hockey gear. And you make it.” After that, “You go back up into your office and you sit for days and days and days thinking: How can I make 600 a minute?”

You buy a jalopy of a bottling machine and rebuild it to do just that. Imagination meets bare hands.

Carmichael tells me Fat Daddy is just one drink he’s working on. A few weeks after my visit, he tells me he’s selected the company’s first product. It’s called Loftiwater, and it features a bubble dubbed Shimmer. The logo is a collection of flying hummingbirds. A group of hummingbirds, Carmichael writes me, is called a shimmer.

Now, here’s the thing about Rebel Beverage Labs. The breakthrough drinks are fun to taste, and the entire concept makes great conversation. But Carmichael isn’t some 25-year-old chemical engineering grad with big ideas. He’s a seasoned brand-builder with nearly 30 years’ experience who has taken his products nationwide. The facility I see isn’t a sprawling 500,000-square-foot warehouse, but it is designed for volume. As Carmichael says, “Sometimes big needs a tiny garden.”

He aims to produce up to 40,000 cases of water per week from this location, though for now he’s focusing just on distributing to the Northeast. That’s on the cusp of what he’d need for national distribution. “By then, the next factory will be built,” he says, and he’ll be able to meet any demand.

He’s already pursuing deals with partners, some of which have the potential to take his business venture big — very big. Carmichael will make and ship the water; the rest — from the name to the brand to the packaging — is up to the client. The important part for Carmichael, other than the revenue potential, is that these will be production deals, not investment situations. Carmichael no longer wants “big money in the room” with his projects, and instead wants to work with individual clients to make their own specific versions of his new creation.

“RBL is about creating a platform where you can play within mouthfeel,” he says. “Now, we’re going to work with other people and say, ‘Okay, what mouthfeel are you’re looking for?’ So you can blend to those kinds of qualities. That’s the science of bubble making — like, what would you like yours to be?”

That distinction is important because Carmichael’s freedom to create is important. No matter how many factories he has to build, he wants to keep this original location for innovations. As he says, “Operations people want to do the same thing better and faster. Innovation has to come from another source.” That source will be this lab and Carmichael’s brain and hands.

The atmosphere and potential of RBL, the optimistic tone of our conversations, plus the cool new drink I tasted might make you think that what’s happening here is a slam-dunk. Nothing is, of course, not even a new business with a great pedigree and product. But as successful as Carmichael has been, he’s not bulletproof. Ideas fizzle. Goals require pivots. His Death Valley trek ended with flat tires on his supply rickshaw instead of a world record, or even a completed mission.

In short, a lot could go wrong here.

For Iberti’s money, this is a new climb with an old partner. They got this. “This is how we’re wired and what we’re good at,” he says. “We didn’t know how La Colombe would turn out, but at the time, we knew it was big. And Rebel Labs, with the beverage and the mouthfeel, it’s kind of the same feeling.”

It will be interesting to visit Carmichael in this bare-bones facility in six months or so. I’m seeing the embryonic stage, the wireframe, the soft opening. I’m curious to see what the final version looks like, because he revisits one theme with me a few times in our talks: creating a space where he can be comfortable. That can be a physical room or even an entire city.

“Look at La Colombe,” he says. “I know why I started it. I was looking for a home. I wanted a place a guy like me could live and work and operate in. Once it takes off, then I can feel myself being a part of this community.”

Now, it’s Rebel Beverage Labs. “In order to be your own hero,” he tells me, “there have to be some courageous moves. I wanted to create an environment for myself. I didn’t become an entrepreneur because I felt I was born to be one. A company or a brand is like a tiny little universe you live in. That made sense to me. So I created an environment that allows me to be me. And you’re now in that space, whether that’s starting up a coffee company in 1994 in Philadelphia, walking across Antarctica, or anything else. When you’re done, you can say, just for an instant at least, ‘Yeah, I’m living the life and I’m creating something bigger than me.’”

Given that when we speak, RBL and its fledgling products aren’t yet up to capacity, I ask Carmichael what will constitute success in this context. And what would failure look like? He doesn’t mince words.

“Here’s what I want to hear: one stupid little sentence. When I go to a restaurant, I want to hear the server ask someone at another table if they want water and say, ‘Still, sparkling … or shimmering?’”

Published as “Todd Carmichael’s Next Big Thing” in the November 2021 issue of Philadelphia magazine.