What Can Philly Do About Climate Change? A Whole Lot, Actually.

You know those digital flood-simulation maps? The ones that show how water will begin to creep into the streets of Lower Manhattan and put it underwater by the end of the century? The ones that could double as preview posters for a dystopian movie? They don’t only exist for New York. There are equally terrifying ones for cities all over the world, from Miami to London to Sydney.

There’s no doubt climate change is a global problem that requires a global solution. But national governments are ponderous. The Paris Agreement, ratified by 186 countries to reduce emissions and prevent global temperatures from rising, was a valiant attempt at collaboration — but three years in, many signers aren’t meeting targets. And still, the waters rise.

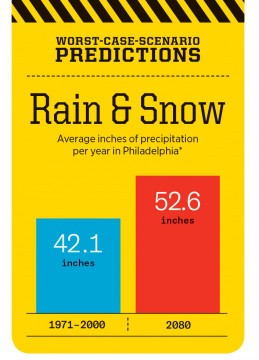

The truth is that environmental policy shouldn’t only be discussed on a national level, and those waterside cities aren’t the only places that will be impacted by shifting climate. Philly is also going to see massive changes from the global crisis, with our city getting hotter, wetter, stormier, and potentially more crowded.

What can we do about it? The Kenney Administration has taken a step in the right direction with its forward-looking goal to reduce Philly’s carbon emissions 80 percent by 2050. But there’s more — a lot more — that needs to be done. On the following pages, we lay out some of the dangers Philadelphia faces in the years ahead, and 10 things we can do to alleviate — or at least prepare for — the impact global warming will have on everything from our airport to the Shore.

Government can lead, but we’ll need action on all fronts to solve this problem. Philadelphia, it’s time to get moving. — David Murrell and Claire Sasko

Photograph by Dan Saelinger

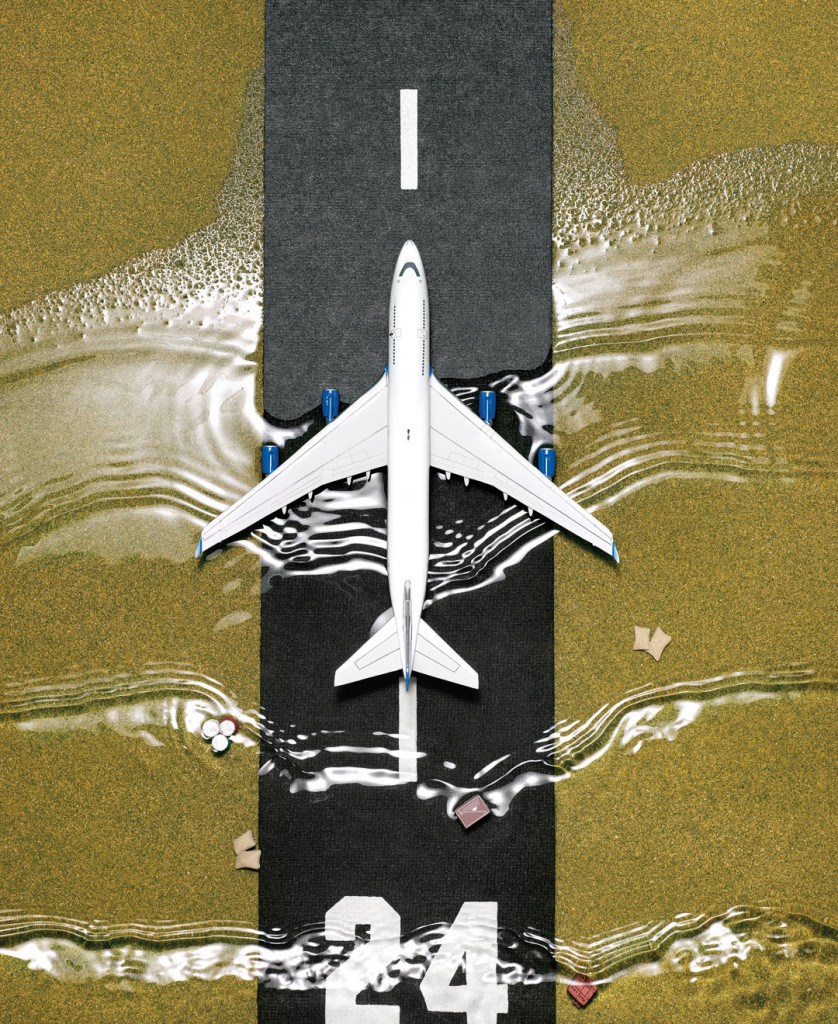

Move the airport before it’s underwater.

Why? Because PHL is going to flood — and sooner than you think.

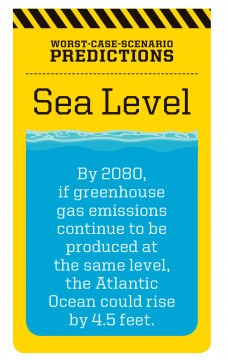

That glittering river you see from your airplane seat that signals you’re almost home is going to be a big friggin’ problem. PHL is set just 260 yards from the Delaware River, and its terminals, runways and cargo carriers are highly vulnerable to tidal flooding that’s projected to become more regular by 2050 and dire by 2100. If sea levels rise by as much as four feet by the end of the century — current projections top out at more than six feet, depending on the extent to which greenhouse gas emissions can be curbed — a Category 1 hurricane would put a majority of the airport underwater. Keep reading here.

Charge people to drive in the city. (And use the money to make SEPTA better.)

Why? Because we’ve got to cut our dependence on cars.

Philadelphians waste more than a millennium sitting in traffic every year. But our horrific state of congestion costs us more than time and money. Transportation is responsible for 24 percent of citywide carbon emissions. And air pollution spikes during rush hour, when idling cars waste fuel. That’s where a congestion fee comes in: To tackle this issue, consumer habits must be broken, and public transportation must become more efficient. Keep reading here.

Photograph by Dan Saelinger

Make it easier to own an electric car.

Why? So vehicles stop gunking up our air.

One reason why some of the 386,000 Philadelphians who drive to work aren’t trading in their gas guzzlers for electric cars: There aren’t enough places to charge up. Philly has only 135 public plugs, a figure that lags way behind the 2017 totals of cities like Los Angeles (1,456), San Diego (776) and Seattle (401).

But beyond infrastructure issues, the city isn’t doing much to encourage electric ownership. Last year, City Council killed a program that let electric car owners pay to have charging stations installed in front of their homes. Critics argued it was a way for rich people to pay for private parking spots. That may well have been a side effect, but the average electric-vehicle owner does 80 percent of juicing-up at home, and ending the program with no alternate plan for charging up brought any progress to a hard stop.

But beyond infrastructure issues, the city isn’t doing much to encourage electric ownership. Last year, City Council killed a program that let electric car owners pay to have charging stations installed in front of their homes. Critics argued it was a way for rich people to pay for private parking spots. That may well have been a side effect, but the average electric-vehicle owner does 80 percent of juicing-up at home, and ending the program with no alternate plan for charging up brought any progress to a hard stop.

Perhaps Philly should look elsewhere for inspiration. Austin Energy (which is municipally owned) has more than 800 plug-in stations around the region and offers a monthly $4.17 subscription plan. Denver has a pay-as-you-use program with stations all over the city and suburbs. Space is no doubt an issue in Philadelphia, so garage and lot owners should be incentivized to put up stations. And government should look at retrofitting what it already owns — like parking meters and those new LED streetlights. (Hey, start-up people: business opportunity!)

There’s also leading by example. In 2017, the Kenney administration had only 188 alternative-fuel vehicles. Now, that number has grown to 35 electric vehicles and 240 semi-electric hybrids — comprising four percent of the 6,200-vehicle municipal fleet. (In Seattle, it’s 17 percent.) That’s not quite the zero-to-60 pace of a Tesla, but it’s a start.

Stop building Shore houses.

Why? Because all those beach and bay homes could be worthless in 30 years.

Approximately no one wants to lose the Jersey Shore as we know it to climate change. But real talk: This is what we face. Think the situation at the coast is nerve-racking now? As of 2017, the record number of high-tide flood days in a year in Atlantic City was 22; in 2050, the town is projected to see between 65 and 155 days of high-tide flooding per year. The rising sea levels could leave more than 250,000 New Jersey homes at risk for chronic inundation — flooding that occurs 26 times or more a year — by the end of the century, according to a 2018 report from the Union of Concerned Scientists. Keep reading here.

Photograph by Dan Saelinger

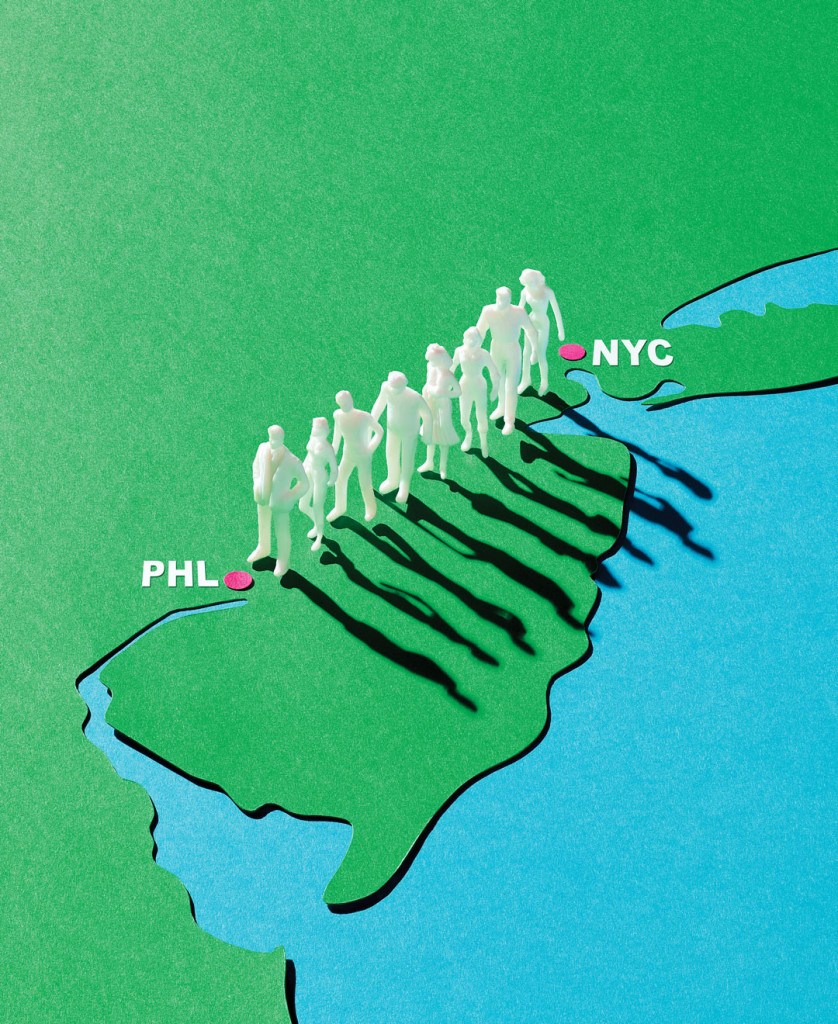

Get ready for hundreds of thousands of climate migrants.

Why? Because lots of people — and, gasp! New Yorkers — are going to descend upon Philly.

A report from the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees states that climate disasters — both short-term issues like coastal flooding and long-term ones like shoreline erosion and agricultural disruption — will displace between 25 million and one billion people around the world by 2050.

It’s difficult to estimate how many might come here, but Mathew Hauer, an assistant professor of sociology at Florida State University, predicts that the Philadelphia metro area could see an influx of 300,000 migrants due just to rising sea levels by the end of the century. In fact, the region ranks fifth in U.S. geographic areas expected to receive the largest numbers of such people, behind Austin, Atlanta, Houston and Orlando.

Philly officials have already told us they’ll welcome climate migrants, including those fleeing countries hit hardest by global warming (probably those in equatorial regions). But the bulk of the newcomers, Hauer says, will likely be arriving from rather familiar places: seaside cities like New York, Boston and Jersey City, all of which are partially located in flood zones.

If that sounds overwhelming, relax: Cities are “almost always better off because of migration,” says Mark Alan Hughes, founding director of Penn’s Kleinman Center for Energy Policy (as well as former mayor Michael Nutter’s chief policy adviser). A 2018 study in the Journal of Economic Geography concludes that when immigrants from a diverse pool of countries live in a metro area, wages increase across the board.

Plus, Hughes adds, Philly can handle it: Our infrastructure may be outdated, but we’re capable of housing 2.5 million people. (The city’s population peaked at more than two million in the 1950s.) Not to mention that Philly would be “cheaper to maintain if it were operating at fuller rates of use.”

That being said, Philly will need to support new arrivals and the existing population. Those who can afford to move will likely be the first to do so. An influx of wealthy Brooklynites or Bostonians could further increase property values and rental prices in the city’s already gentrifying neighborhoods, potentially leading to displacement or migration within Philly. That’s why, says Hauer, city officials need to plan for “equity concerns.” One way to encourage a seamless transition would be to create a climate-migration-focused branch of the Office of Immigrant Affairs, which could track migration data, engage business leaders and inform policies.

Photograph by Dan Saelinger

Make the tax abatement green.

Why? Because we need better buildings.

Pop quiz: What’s the biggest source of greenhouse gas emissions in Philly? If you said cars — wrong! The answer is our buildings — which, thanks to inefficient heating and electrical systems, generate even more bad stuff.

How to tackle that? One easy way is to tweak the controversial city real estate tax abatement, which lets owners avoid paying property taxes on new construction or building renovations for 10 years. Many people use it: A recent study found that from 2007 to 2017, 10,435 new buildings took advantage of the break.

Now, imagine if the abatement had one big green string attached: To snag that sweet tax deal, builders have to earn an Energy Star score of 75. (ES derives its rankings by comparing greenhouse gas emissions from buildings of similar size and function. A score of 75 means a particular building outperforms three quarters of its peers.) If that had been done back in 2000, when the current form of the abatement went into effect, well over 10,000 buildings might be energy-efficient today.

A policy like this would have a major impact in the future, but the city shouldn’t discount its ability to deal with inefficient buildings that are already standing. Large buildings are required to report their energy consumption to the city, but at the moment, that info isn’t good for much except public shaming. To tame these carbon guzzlers, the city must look not to incentivize, but to penalize. New York City has already drafted a blueprint with a policy that will fine buildings emitting beyond certain carbon thresholds beginning in 2030. If Philadelphia adopted the same standards, offenders would be inspired to clean up. Take the Marriott Downtown hotel as an example. If it maintains its current level of emissions, it would be fined $1.47 million each year from 2030 on.

Plant more trees in low-income neighborhoods.

Why? Because the temperature gap between rich and poor neighborhoods isn’t fair.

Between 1961 and 2000, Philly experienced an average of four days per year when the temperature went above 95 degrees. By 2100, the city could see between 17 and 52 such days annually. But those A.C.-busting numbers don’t tell the whole story, because there’s another element to consider: the fact that there are significant temperature variances within our city.

Hotter neighborhoods are, not coincidentally, more building-dense. This “urban heat island effect” occurs because buildings and asphalt absorb heat, leading to hotter air. Vegetation actually reduces air temperature through a process called evapotranspiration, which is analogous to the way our bodies cool when we sweat. Plus, trees provide shade and absorb carbon dioxide, a leading greenhouse gas.

Unfortunately, there’s a strong correlation between high poverty rates and lack of trees in Philly neighborhoods. Areas with comparatively low median household incomes — Hunting Park, Strawberry Mansion, and parts of Southwest Philadelphia, for instance — can be as much as 22 degrees hotter than leafier, and often wealthier, blocks in Center City and parts of West Philly. The city’s heat vulnerability index also shows that black people, Latinos, and other residents of color are more likely to live in the hottest neighborhoods. As a result, these residents — especially the elderly and those without air-conditioning — are more prone to heat-related illnesses and death.

This past summer, the Mayor’s Office of Sustainability released its first-ever Community Heat Relief Plan, which proposed adding more vegetation to vulnerable areas. But the Department of Parks and Recreation won’t plant a street tree without a property owner’s permission, putting areas with vacant buildings at a disadvantage. Philly should follow in the steps of New York by removing this barrier to greenery, and low-canopy neighborhoods should be prioritized over tree-dense ones. Officials could also allocate more funding toward these programs: According to PlanPhilly, there’s now enough money to plant just 1,000 saplings a year, which renders the city’s tree canopy goal of 30 percent by 2025 unrealistic. And if the city can’t afford it, corporations should chip in, supporting the communities where their workforces live. Here’s a solid opportunity for PECO to offset its environmental impacts by helping to green our city.

Strong-arm the blown-out South Philly refinery into becoming a green energy complex.

Why? Because it’ll reduce pollution and create jobs.

When it comes to air pollution in Philly, there’s no single greater offender than Philadelphia Energy Solutions, says the city’s Office of Sustainability. When the South Philly oil refinery complex owned by PES was fully operational, it was responsible for 72 percent of our toxic air emissions, according to a report by the NAACP and the Clean Air Task Force. For a city with an asthma rate that far exceeds the national average, that’s a problem.

![]()

The 1,300-acre property just northeast of the airport has been in operation since 1870 and has a long history of air pollution and soil and groundwater contamination. What makes an already bad situation worse is that the site hasn’t been financially viable for years. When the complex’s former operator, Sunoco, said it would have to shut down operations in 2012, city, state and federal officials stepped in to provide last-minute help — including $25 million from Pennsylvania taxpayers — to keep it running. (Because: jobs.) Then, in 2018, new owner PES declared bankruptcy. (A report published that fall by Penn’s Kleinman Center for Energy Policy said the refinery’s bankruptcy plan “did nothing to change the fundamental structural challenges facing the refinery” and failed to address future issues like “increased competition from Midwestern refineries.”) And then there was the big boom: the infamous explosions this past June that plunged the complex into yet another bankruptcy. PES was finally forced to put up a FOR SALE sign.

The 1,300-acre property just northeast of the airport has been in operation since 1870 and has a long history of air pollution and soil and groundwater contamination. What makes an already bad situation worse is that the site hasn’t been financially viable for years. When the complex’s former operator, Sunoco, said it would have to shut down operations in 2012, city, state and federal officials stepped in to provide last-minute help — including $25 million from Pennsylvania taxpayers — to keep it running. (Because: jobs.) Then, in 2018, new owner PES declared bankruptcy. (A report published that fall by Penn’s Kleinman Center for Energy Policy said the refinery’s bankruptcy plan “did nothing to change the fundamental structural challenges facing the refinery” and failed to address future issues like “increased competition from Midwestern refineries.”) And then there was the big boom: the infamous explosions this past June that plunged the complex into yet another bankruptcy. PES was finally forced to put up a FOR SALE sign.

But all of this drama presents a rare opportunity to replace a giant fossil-fuel producer with a green energy hub that aligns with the city’s stated clean-energy vision. While the site is privately owned, political influence in high-consequence deals like these shouldn’t be underestimated. Officials used their clout once to save the site: Now they can wield their leverage to help transform it into something better. A report expected soon from the city’s Refinery Advisory Group (created in the wake of the explosions) will include recommendations for developers eyeing the site, who will ultimately seek approval from U.S. Bankruptcy Court. Philadelphia managing director and group co-chair Brian Abernathy has said the report won’t prescribe a favored outcome. Yet that’s exactly what the city and the state need to do.

Suitors (so far) include a California-based real estate development and investment firm, local renewable biofuels company SG Preston, and the newly formed Philadelphia Energy Industries, helmed by Phil Rinaldi. Rinaldi, also known as “Fossil Phil,” helped facilitate the push to save the refinery in 2012. Officials should discourage history from repeating itself. Renewable energy companies like SG Preston, with its biofuels — which use sources other than fossil fuels and oils, like plants or waste, to create energy — could be financially incentivized to turn the giant parcel of land into a place that produces greener energy and pollutes the air and ground less.

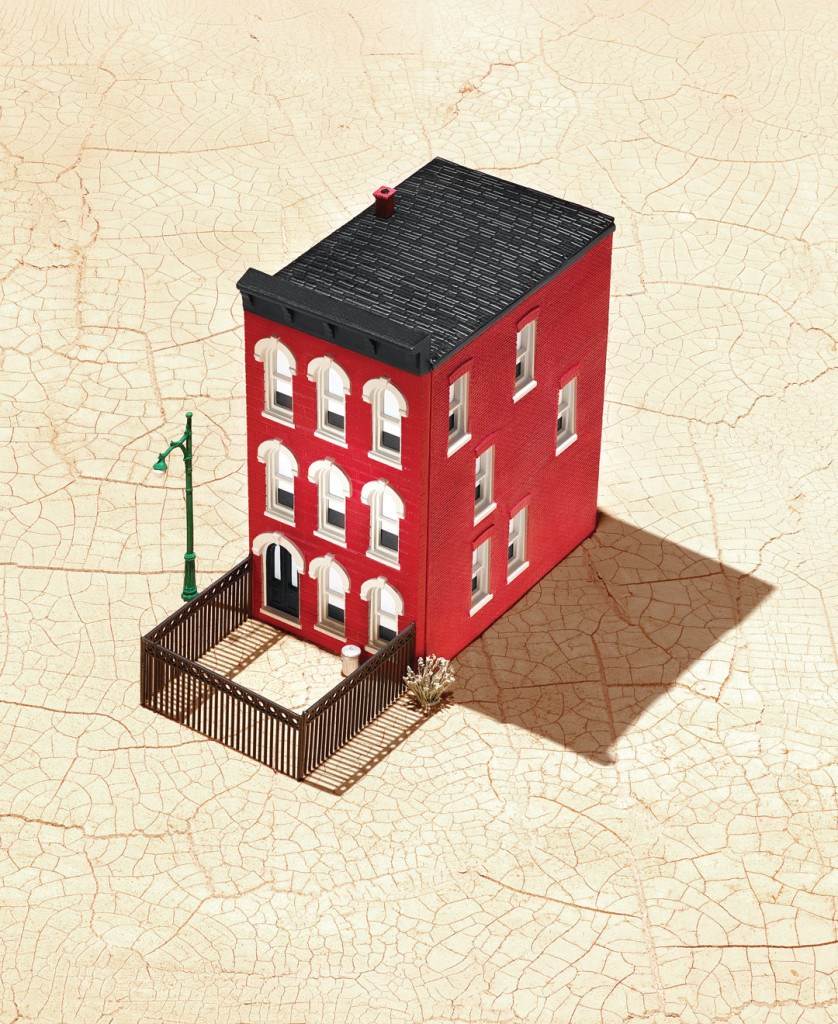

Demand riverside buildings be lifted even higher.

Why? Because flooding is going to be our new reality, and our building codes must reflect that.

Philadelphia isn’t right by the ocean like New York and Miami, but don’t assume that means we’re high and dry. There’s still going to be a lot of flooding, and it will pretty much come in two different forms. You’re familiar with the first: a massive downpour overwhelms our old sewer system, leaving water overflowing in the streets. (And when the system is really taxed, waste winds up in our rivers.) The issue is only getting worse. Last year the city saw 62 inches of precipitation, an all-time record.

Related: The City’s $200M Plan to Save South Philly’s FDR Park

The second kind of flooding has less to do with bad weather. The Schuylkill and Delaware are both tidal rivers, meaning they rise along with the Atlantic Ocean. And rising sea levels have been causing the rivers to inflate to a point where even a small amount of rain can cause a flood. The city’s current record of “high-tide flooding” days in one year is 12. By 2050, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration expects that figure could grow to anywhere from 30 to 105 days.

To combat stormwater, the Nutter administration in 2011 launched Green City, Clean Waters, a $2.4 billion infrastructure commitment that pledged to use more penetrable surfaces — porous pavement, green roofs, cisterns that collect water for trees — so rain gets absorbed before it even gets to the sewers. (The plan has drawn praise from environmentalists.)

But that doesn’t help much with riverine flooding, which is arguably a more significant problem, since it imperils valuable parcels of land like the Navy Yard and the Delaware River waterfront. Construction in these areas must be designed to mitigate flooding. The problem is that developers don’t typically think about future flood levels, explains Richardson Dilworth, director of the Center for Public Policy at Drexel University; they’re more focused on ROI. “As long as you’re recouping costs early on, climate change is not going to incorporate itself so heavily in your financing,” he says.

But that doesn’t help much with riverine flooding, which is arguably a more significant problem, since it imperils valuable parcels of land like the Navy Yard and the Delaware River waterfront. Construction in these areas must be designed to mitigate flooding. The problem is that developers don’t typically think about future flood levels, explains Richardson Dilworth, director of the Center for Public Policy at Drexel University; they’re more focused on ROI. “As long as you’re recouping costs early on, climate change is not going to incorporate itself so heavily in your financing,” he says.

Fortunately, the solution is simple — and free! Currently, construction codes mandate that new buildings at risk of flooding be either flood-proofed or elevated 18 inches above expected flood levels. That’s not forward-looking enough. That 18-inch designation is based on historic trends, not future ones, and doesn’t account for expected rises in sea level. Codes should be amended so that any new construction uses a projected 2050 flood zone as a baseline. (It likely won’t be as high as the five-foot buffer encouraged by the city of Miami, but 18 inches from current levels isn’t enough.)

And what of the buildings that are already there? They’ll likely require some form of retrofitting — or, at the very least, that vulnerable mechanical systems be moved to higher floors. Today, we know two things: Water levels are rising, and buildings are meant to last decades. Our building code must reflect that.

Bring city stakeholders together and turn a crisis into an opportunity.

Why? Because we need the boldest, smartest leaders on this right now. (Also, because it’s good for the economy.)

Here’s one advantage to the sputtering progress the United States has made on climate change: No city has yet asserted itself as the undisputed national center for climate technology and research. The single-city monopoly has tended to be the model when it comes to American innovation — think Silicon Valley and tech; Detroit and automobiles. There’s a huge economic opportunity beckoning in the still-nascent clean-energy industry — for any city that cares to look, that is.

Why couldn’t it be Philly? In 2017, Philadelphia had the 12th-most clean- energy patents of any metro area in the country — and that’s without any sort of centralized push. (Silicon Valley, unsurprisingly, tops the list.) Imagine how a public-private initiative — one that unites politicians, business, academics and nonprofits for the singleminded task of innovation — could vault us higher. Example: Could the smart people at universities like Penn and Drexel (each with its own center for energy research and policy) come up with a way to replace the fossil fuel distributor PGW, whose natural gas causes 22 percent of citywide greenhouse gas emissions?

One way to kick-start this activity: City government could promote climate-related tech R&D tax incentives (attracting new businesses and jobs) and connect big energy consumers like SEPTA to clean-energy tech providers (so our investments stay in the local economy). It’s a win-win: save the planet and make truckloads of money. Who’s going to say no to that?

Published as “What Can a City Do About Climate Change?” in the November 2019 issue of Philadelphia magazine.