Fishtown: An Oral History (So Far)

Photograph by Christopher Leaman

When people talk about Fishtown, they talk about how it started as a tiny fishing village in the 1700s. They talk, too, about how it used to be back in the ’60s and ’70s, a tight-knit enclave of working-class Irish-Catholics; and about how the drugs came in and decimated the area in the ’80s and ’90s. And some talk about how people said they were crazy when they decided to come here in the early aughts, back when Fishtown’s commercial corridors were a neglected no-man’s land.

But people talk mostly about how, exactly, Fishtown got to where it is today — Philly’s most buzzed-about neighborhood, a place emblematic of how the city has changed and is changing. They talk about Roland Kassis, Fishtown’s prime developer, who rebuilt those commercial corridors. They mention Stephen Starr, who put Fishtown 2.0 on the map with a German beer garden, of all things. And, finally, they talk about everything that’s happened since — all the small businesses, big developments, rising rents, shifting demographics and growing pains that go hand-in-hand with neighborhood revitalization.

But Fishtown is actually very much still in transition, and its next chapter is arguably its most important: The neighborhood is either going to continue its surprising, only-in-Philly transformation, or eventually transform into … Brooklyn.

Here’s the story people tell about Fishtown: the modern history of a neighborhood’s dramatic change, remarkable rise and hopeful future. —Emily Goulet

— I —

The Old Neighborhood

“Fishtown was a village.”

Before the artists and the yoga studios and the out-of-towners came, Fishtown was a quintessential white, working-class neighborhood — but one that went into decline as the 20th century came to a close.

Cass Sparks, resident: I’m 85 now, and I’ve lived in Fishtown all my life. The truth of the matter is, this neighborhood stayed so tight because you didn’t really have the means to move anyplace else. What you had in your home was what you had, and you took care of it because you knew it was all you were ever going to have.

Denise Mayer, resident: I’m a sixth-generation Fishtowner. I was born in 1973. That’s how it was — your kids went to school together, you would go to parties together, your kids would end up growing up and marrying each other. It’s just the way it works.

Maggie O’Brien, resident: My husband and I have lived here for 35 years. We raised our kids here; now my grandchildren live here. The whole neighborhood was like one big family, really. Fishtown was a village. Everybody knew each other; everybody looked out for each other. Over at Shissler Recreation Center, which we called Newt’s back then, the field used to be made of cinder. I was at soccer games there with my kids where people from the other team tried to drive on the field. We would laugh about it: “My kid had a game at Newt’s today and the other team thought it was a parking lot.”

Sparks: It was a poor neighborhood. Not poor; people held their own. They all had jobs. We had so much industry — sweater mills and sock factories, cigar companies, the SugarHouse.

O’Brien: We were kind of forgotten. We lacked a lot of services from the city. Like we were just ignored, basically, until we got SugarHouse in 2010, which donates $1 million a year to the community. The politicians — I never even saw these guys come into our neighborhood until they were on their way to jail.

Clockwise from top left: Marge, a bartender at Les & Doreen’s; new and old homes on East Hewson Street; longtime residents outside Les & Doreen’s; a tangle of Fishtown footwear. Photography by Christopher Leaman

Margaret Garcia, former longtime resident and director of operations at Fishtown’s Lutheran Settlement House: Back in 1975, the El was a very big dividing line. When I grew up, blacks and Hispanics were on one side, and whites were on the other side. If a family of color — different religion, ethnicity — moved in, people were putting sale signs up; they were moving. Fishtown was a heavily populated Irish-Catholic neighborhood, and people don’t like different.

Ken Milano, Kensington resident and area historian: I talk to African American people today and they all say the same thing: It was known you never went to Fishtown if you were black. I witnessed fire bombings when I was a kid, maybe around 1970 or so? A family tried to move in, and their house got burned down. But it seemed like the drugs sort of took out the racial component. The drug dealers and drug users all sort of got along.

Carrie Hunter, former longtime resident: Frankford Avenue and Front and Girard — you weren’t allowed to go there. Walking where Frankford Hall and Johnny Brenda’s are now, that was considered dangerous at nighttime. I’m not saying guns, gang dangerous, but it was not developed; people really didn’t live there.

Milano: Drugs started coming in, and that whole area under the El really started to deteriorate. When I was a teenager in the 1970s, there were still factories open, but they were leaving, closing, burning down. It seemed like there was always something burning down. The riverfront was becoming kind of desolate. And the 1980s is when the crack cocaine started, and that was a scourge on the Earth. So that whole neighborhood just went under.

Mayer: In the mid-to-late-’90s, the Catholic schools started to close. The drugs were changing. Once the pharmaceutical pills and drugs came into it, that was it. It was a whole new ball game.

Garcia: It was deemed a neighborhood of addicts. People were moving out at the speed of light. There were overdoses all over Fishtown. In January of 2001, we went to three opioid funerals in one week, Thursday, Friday, Saturday.

O’Brien: The cops were not able to do anything, and we just wanted to stop it. So every Friday and Saturday night, a gang of Fishtown neighbors would pick corners and go out with beach chairs and sit there and try to get the drug dealers to move.

Garcia: I remember people doing that, sitting on a corner. That was when the epidemic was at its breaking point. I think it was around 2000 that people started saying, “We’re going to take back our neighborhood.” And those were the people who decided to stay and fight.

— II —

The Rebirth

“Everyone thought I was crazy.”

By the late ’90s and early 2000s, Fishtown had arguably hit rock bottom. But where some people saw despair, others saw opportunity. Drawn by former industrial spaces and cheap real estate, artists and makers began moving in alongside the longtime residents. The neighborhood soon caught the attention of some visionary business owners, including two people who’d had success in nearby Northern Liberties: bar owners Paul Kimport and William Reed, who opened gastropub Standard Tap there in 2000. There was also Roland Kassis, a Lebanese immigrant who quickly made a name for himself in NoLibs as a residential builder. After a few years, Kassis set his sights further north, scooping up some prime Fishtown properties for future development.

Denise Mayer: The artists were so scattered, people for the most part didn’t even realize they were moving in. Slowly but surely, that’s what it was.

Helene Mitauer-Rosanio, resident and artist: The reason I moved here, back in 2001, is because my husband said, “This is the place to go, you can buy a house really cheap, and this is going to be the next Northern Liberties.” And I had friends and artists that were living close to here and had studios. It was becoming a place for everyone to go to find a new space, because all the spaces in other areas were gone or they were too expensive. I was excited about how we could start a resurgence of art in this area. But it was rough. I thought I had made a real mistake.

Heather Rice, former resident and owner of Amrita Yoga: In 2003, I had two dogs and I was 23, 24 years old, so cost and dog-friendliness brought me to Fishtown. Everyone thought I was crazy for moving there. People just didn’t move to Fishtown then. I only had one friend that ever came and visited me, because people were so scared of it. Fishtown was really the Wild West back then. There were wild packs of dogs that used to run around the neighborhood. I’ve seen horses running around because there used to be stables here, and they would sometimes get out. It was like anything went in Fishtown. But there was something about it.

Outside Fishtown Tavern. Photograph by Christopher Leaman

Paul Kimport, resident and co-owner of Johnny Brenda’s: In ’03, I got the courage to think about looking for a house in Fishtown because I knew some friends that lived on the block, some musicians. They called it the “rock block” then. From the very beginning, as sort of an entrepreneur-thinking person, it struck me as this really undervalued community. It seemed well-built in terms of the hardscape and the building stock and its situation with the El. And it seemed like Johnny Brenda’s was right in the very crossroads or gateway of things. When we bought the business Johnny Brenda’s from Johnny Brenda’s wife, I think she said something like, “It’s a great buy — the Irish love to drink!”

Mayer: Well, I think everybody thought that they were crazy because that was always a dirty-bum bar. All the people who weren’t welcome in the other bars drank there.

Kimport: We started serving the arts market — some of my neighbors, my peers, artists, musician friends, makers, that sort of thing. After we opened, some people would say, “Everybody’s talking about how much money you’re charging for beer in there.” One time, somebody showed up and was like, “Man, I tell ya, you’re away in prison for one year, and you come back and it’s a goddamn hipster bar!”

Mitauer-Rosanio: Slowly but surely, I noticed new businesses, new little cafes opening up with obscure names that I thought were very unique, ideas about having galleries in the cafes …

Roland Kassis, developer: I’d been a residential builder in Northern Liberties since 2003. I was building high-end homes then. The property where La Colombe is, we bought that property first in 2005, just buying inventory. The plan was to demolish the building and build homes on it. It was dilapidated, beat-up, falling apart, like everything else on the corridor. But that neighborhood had a soul. When the world crashed in ’08, we took a step back. I watched Bart [Blatstein] build the Piazza during that era, and he had to build streets, put in lights and sewers. He spent a lot of money on infrastructure. I realized that Fishtown was a more developed neighborhood. We already had an infrastructure on Frankford, Front Street and Girard, so why not turn these streets into cool spaces?

Mayer: When I met Roland, we shared the passion for Fishtown. He saw it for what it was. The vision that he had — he knew it was a special place. I work with him now as his controller.

Kassis: People always used to say, after Northern Liberties, the new up-and-coming neighborhood would be Fishtown. For me, it’s like, what are these people talking about? Fishtown’s a great neighborhood; it already came. It’s already there. Fishtown has been a neighborhood for generations and generations. The only thing that was missing was a commercial corridor. That’s all it needed.

— III —

The Starr Invasion

“It’s going to change everything.”

By 2010, Roland Kassis had purchased huge swaths of property in Fishtown. But to make the neighborhood really take off, he knew he needed some kind of outside investment. He found it in Philly’s most successful restaurateur.

Roland Kassis: I saw what Stephen Starr did in Old City with the Continental; he changed the whole area. We knew with Stephen coming to the neighborhood, the outsiders’ perception of Fishtown would change. I chased Stephen for a year. He’ll schedule a meeting, then he’ll cancel at the last minute. Finally I said, “I’m going to do a restaurant myself.” My structural engineer introduced me to [architect] Richard Stokes. Richard comes over and he’s like, “Did Stephen see this property?” I said, “I’ve been chasing him for a year now.” He calls Stephen, and Stephen’s there in 15 minutes.

Stephen Starr, restaurateur: I gravitate toward places that are on the fringe, a little off-center and hidden away. I’m also a total junkie for spaces. Frankford Hall was this bombed-out building, rubble with no roof. I walked in and I said, “Oh my God, look at this. Let’s just leave it as it is and we’ll make it a beer garden.”

Inside Frankford Hall. Photograph by Christopher Leaman

Bill Russell, artist: My first thought? Suspicion. I’ve been in the building across the street since 1997. That Frankford Hall property had been an automobile dealership. I think it shut down sometime in the ’60s. At one point, the guy that owned it parked buses in there, tour buses that went down to Atlantic City.

Starr: That’s what’s wonderful about Fishtown. You can take old buildings that have some character, and inside they’re usually all messed up, and you just re-create something in these empty canvases. Much more satisfying than going to a traditional space in Center City where you have to squeeze an idea into spaces that don’t necessarily want it to be there. It was liberating to be there.

Paul Kimport: Stephen Starr’s zoning advisory meeting was a big event. Everybody wanted to come out and give him a hard time about building some yuppie whatever. But the way I describe it, he took a leveraged position of some sort of Buddha master where he reversed the energy. It was the most brilliant thing I ever saw.

Kassis: What happened is, Stephen got up and said, “I don’t need to be here if I’m not welcome.” That’s what Stephen said.

Starr: I really don’t remember it. We probably used visuals? I think Roland had a lot to do with making them feel more comfortable with us, because he had already established roots in that neighborhood.

Kassis: I remember that Bill Russell got up and spoke. When I first showed Bill the renderings, his eyes should have lit, you know? But Bill showed no emotion, and I’m like, are you kidding me? If I owned a business here, I’d be ecstatic! But Bill got up at the end of the meeting and said, “This is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to have a developer like Roland Kassis and a restaurateur like Stephen Starr want to come to our neighborhood and open a place. So let’s not blow it up.” That was his closing statement. That was something I was going to say, but he said it for me.

Russell: I don’t get up and proselytize at zoning meetings. But I didn’t get the sense that these guys were going to let it go bad. It’s a crapshoot, and the odds looked good to me.

Kassis: One hundred and eighty-one people showed up for the meeting. We had 173 yeses and eight no’s.

Heather Rice: I think Frankford Hall put Fishtown on the map because Stephen Starr’s name was familiar to people. I think Roland Kassis is responsible for making Fishtown popular. Stephen Starr just made people feel comfortable going there and having a beer. Roland Kassis had a vision, he worked hard to achieve that vision, and we can see that that vision has really changed Fishtown.

Kassis: I remember when we first opened the place [in 2011], we stood across the street and I looked to my left, looked to my right, and there was nothing there. Frankford Hall looked beautiful, just like the rendering looked, the trees out there, the lights, but there’s not a soul on the street. But I had a feeling. I knew right there and then that once we opened, it was going to change everything. And it did.

— IV —

The Boom

“This is the next Brooklyn.”

Stephen Starr’s success with Frankford Hall gave Fishtown two important things: a steady stream of visitors who could see how cool the neighborhood was becoming, and validation that businesses could succeed there.

Margaret Garcia: Frankford Hall was really the first thing that came into the neighborhood that was different. You didn’t have a beer garden. Johnny Brenda’s had changed on the inside, but Frankford Hall was a transformation of the building. And then Roland moved up the block, and you could just see him coming into the neighborhood. The first thing I noticed was the tattoo parlor and the hairdresser.

Tim Pangburn, owner of Art Machine Productions tattoo studio: It was just an abandoned warehouse before they subdivided it. I remember coming in one day when it was raining and there were waterfalls pouring into it. The first six months I was here [in 2011], our Google street view was an abandoned warehouse with a homeless guy on the steps.

Denise Mayer: Let’s not forget about the yoga studio, Amrita, opening in 2011. She was a big draw. Art Machine, she was early in, and Jess Bernard from the Parlour hair salon, who won award after award. And then people just got exposed to the area in a new way, and that was it. That was the domino effect.

Amrita Yoga. Photograph by Christopher Leaman

Pangburn: There were all these smaller places that were bringing in the kinds of people who would take an interest in developing a community here. Momentum was building before La Colombe came in, but that cemented it.

Todd Carmichael, co-founder of La Colombe: About six years ago, we found this property. It was a raggedy mess — abandoned cars and standing water and dead pigeons. Out of every 10 calls I got, nine of them were, You’re crazy. This is ridiculous. I went to Stephen and go, “How are you feeling about Fishtown?” He goes, “Love it.” And I went, “Well, that’s all I need.” We would say over and over, “This is the next Brooklyn. Except we don’t want it to go completely Brooklyn.”

Michael Garden, real estate agent: A huge factor is the shift of urban living in terms of a lifestyle decision. But what came first: the desire to live in a city, or people making communities in the city more desirable? And the answer is, they both sort of happened at the same time, one in response to the other. But Fishtown would not have the housing boom that it’s had without that commercial corridor.

Outside at Johnny Brenda’s. Photograph by Christopher Leaman

Mike Supermodel, former resident and owner of Jinxed: You still had a good percentage of Fishtownies, people that have been there for generations that decided not to leave. But there was enough vacant property, and enough property kicking around in people’s families that got sold, to start bringing in people from around the country.

Maggie O’Brien: Some are from the suburbs or Jersey or whatever, but a lot of them are from New York, Washington, Ohio and Iowa, which I always find odd. But it seems that there’s a lot of people from Iowa.

Mike Quinn, resident: I bought my house in ’04. After Frankford Hall hit, that’s when it was like, all right, now you’ve got a new breed of people coming in and taking over. They’re hipsters, but with money. Back in the ’80s, they would call them yuppies, young people with money.

Garcia: Then we watched them develop Mulherin’s, which was an eyesore for years. People in the homes on the other side of Front Street would put signs in their windows that said, “No hookers on the step.”

Randy Cook, co-founder of Method Hospitality, which runs Wm. Mulherin’s Sons restaurant and hotel: Before we opened in 2016, there weren’t many restaurants that had an average check over $25 in that neighborhood. We saw Mulherin’s as an opportunity to do something a little more elevated. I knew there were sophisticated people moving into the area, and they were looking for something that wasn’t being offered at that time.

Josh Olivo, former resident and developer: That was another turning point, when they opened. They took it to the next level, instead of just craft beer and gourmet burgers. And you can argue whether it’s a cart-before-the-horse situation, but as each of these businesses came up, they served a different demographic.

— V —

The New Neighborhood

“It’s not my Fishtown anymore.”

As new businesses moved in, so did new people, and before long, a proud community of longtime Fishtowners was facing new neighbors (millennials and “yuppies”), a new housing market ($600,000 homes), a new culture (draft lattes and Teslas), and a new normal.

Phil Migliarese, resident and owner of Balance Studios: My neighbors all became musicians, artists, that sort of thing. I’ve seen families move in and move out. There were shifts in real estate taxes so they got priced out, or they moved because of the schools. Now the school’s great, so it will anchor people more to the neighborhood. But it seems like they’re just knocking down the little places and making gigantic places so more people can move in.

Margaret Garcia: My generation, the baby boomers, are amazed at the way this real estate is being marketed in Fishtown. When we were kids, we couldn’t get far enough away from the El, because it made noise. Now, the ingenious way of marketing it to outsiders is, “It’s close to transportation.”

Maggie O’Brien: And [the houses] are ugly! They look like doctor’s offices from 1963, and there are people who will pay $600,000 for it.

Parking off Frankford Avenue. Photograph by Christopher Leaman

michael Garden: The real shift in prices didn’t happen until post-2011, when the commercial corridor was really starting to expand. And that shift has not let up. In 2013, the average sold price in Fishtown was $206,549. Jump forward to January through September of 2019 and we’re at $356,721. That’s a 75 percent increase. That’s a historically incredible, unprecedented leap. And now houses are starting to just barely break the million-dollar mark. I think if you fast-forward five years from now, housing prices will be higher in Fishtown than in Northern Liberties.

Concetta Quinn, resident: I moved here in 2008, and now I get calls almost every day saying, “Hey, this is Morgan! You don’t know me, but I’m looking to buy houses and do rehabs in your zip code. We’d be more than willing to look at your house and give you an estimate of what we would pay for it!” I literally get three of them a week.

Migliarese: I don’t see the market slowing down, even in a recession. I know too many of the people involved in it, and no one’s in it to lose. And a lot of the money coming in is not Philadelphia money. One day, on my little block, every single car parked on the street was New York plates. Every single one. We thought it was a joke.

roland Kassis: Yeah, New Yorkers always come to me, they want to buy. We were able to buy a lot of the land and the large parcels here — and thank God we did. If we didn’t do it that way, then shit would be built.

Justin Rosenberg, founder of Honeygrow: There was a Forbes article that mentioned Fishtown — I think it was Forbes? I sat there with my mouth open. And Joe Beddia is named best pizza in the country or whatever. Suraya getting national awards … how do you describe it? It’s almost like, shit, who expected that? And I don’t think anyone was trying to make that happen. We certainly weren’t. We came here because we needed a commissary.

Nima Etemadi, co-owner of Cake Life Bake Shop: Somehow it’s got to the scale where Fishtown is starting to bring in people who would have never gone to Philadelphia before. It’s really remarkable in terms of how quickly that happened. Even in 2012, when I moved here, there wasn’t really much to do.

Kassis: It’s not me that did this. It’s all these business owners that put their life savings on the line, took all these risks to build these places. They believed in the vision when there was nothing there, when there was not a soul in these streets. People were like, “What are you fucking talking about? Who’s going to come here?” But they believed me.

Josh Olivo: To me, that 10-year span, 2008 to 2018, was more about urban renewal than gentrification. Now, I guess one person’s urban renewal is another person’s gentrification, so it’s all in your perspective. But to me, when you look at a commercial corridor and it’s bombed-out buildings and vacant land, that’s just not okay.

Cass Sparks: I think it’s been a long time coming. I like Frankford Avenue. Suraya, that’s one of the most popular restaurants in the neighborhood. I like it! As a matter of fact, for a while, you couldn’t even get a reservation; they were booked up.

O’Brien: I go to the new restaurants, but I don’t go to all of them. My husband says about some of them, he says, “Oh my God, I’m not eating that stuff, it looks like dinosaur shit.” Not that he’s ever seen dinosaur shit.

Ken Milano: It’s not my Fishtown anymore. I mean, there’s a lot of positives for it, but just as many negatives, I would think. Nowadays, the new people stick out to me like a sore thumb. They shop different, they eat different, they drink different. Most of the bars now are new-people bars. They don’t even open up at six o’clock in the morning. You’re lucky if they open at lunchtime. I’ve seen some Teslas, some Porsches parked on Frankford Avenue, which is kind of funny. See them little Cooper cars, the Mini Cooper cars? That’s a new person right there, you know that.

Joe Beddia, owner of Pizzeria Beddia: Frankford Hall’s not really my cup of tea. The neighborhood was great just with Johnny Brenda’s. It was a different crowd back then. Now it’s more collegiate or something. The Frankford Hall thing … I don’t know if that’s a good thing, actually. It definitely helped to transform the neighborhood on a larger scale, but now we have new construction that’s all pretty shitty.

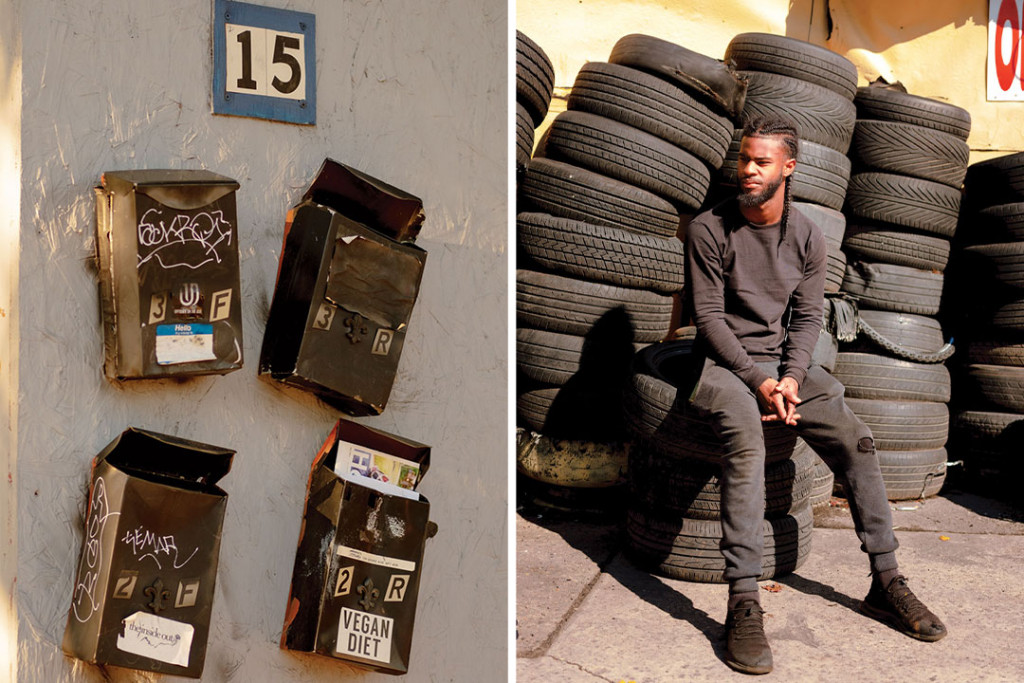

Mailboxes on Girard Avenue; Nelson Diaz at his uncle’s tire shop. Photograph by Christopher Leaman

denise Mayer: In general, the sense of community that we had is slowly being chipped away. There are a lot of people who are coming in and trying to build their own communities, and I give them a ton of credit and I hope that they succeed, but right now is that ugly middle ground, you know? It’s growing pains. And it’ll never be what it was.

O’Brien: But you know what? Every neighborhood changes. We’re lucky that it changed for good. But that’s a big difference, going from a working-class, blue-collar neighborhood to a lot of lawyers and artists and young professionals. It was always like we had the best-kept secret in Philly here.

Olivo: You can talk to certain people who feel the curation of the neighborhood has left them behind. Not even financially, but culturally. I feel like it’s not so much that coffee at Dunkin’ Donuts costs less than coffee at La Colombe, but culturally, the corridors were rebuilt to reflect the personality and values of creative, design-oriented … like, hipsters, dude. For lack of a better word.

Bonkosi Horn, resident: There is a lot of us-vs.-them, the old people vs. the new people. You can see it if you look at any Fishtown neighborhood Facebook group. But at the end of the day, our goal is to have all of those things that they talk about, too — things like looking people in the eye and smiling at them, cleaning up the street, taking care of the neighborhood. Being from the Midwest — I’m from Iowa — I really value community, so this feels like home to me.

— VI —

The Future

“It’s still not moving fast enough for me.”

After years of dizzying change, Fishtown is now at a crossroads: How does a place keep its soul while moving into the future? An evolved neighborhood — lifers and artists and hipsters and millennials and families — looks forward, its sights on developing, diversifying and preserving.

Heather Rice: I think Fishtown faces a choice. It can go two ways. It can become like a Disneyland. Or we can hold true to our values and be an example for Philadelphia on how you can grow and get national recognition and have corporations, but how you can also somehow figure out a way to still allow and support local business and uniqueness and character.

roland Kassis: That was my goal when we developed it — to make sure that everything’s getting developed organically. But we want it to move. Is it moving fast enough? It’s still not moving fast enough for me. We’re not even 50 percent there yet.

todd Carmichael: We have to pace ourselves. Let’s not go nutty — no strip malls, no giant high-rises and high-rise parking lots. What you don’t want to do is have a forest fire go completely out of control. Then you get Brooklyn. You want it to be a really nice bonfire, but you don’t want it to just start burning things down.

justin Rosenberg: We’re not paying Center City rents. We wanted to be here because we wanted to be kind of away from it all, and once you become the center of attention, are you going to attract what you’re trying to get away from?

paul Kimport: That’s the goal — to make a community that is accessible but also special in some ways. And the best way to do that is diversity of housing stock, so younger people, younger artists, can afford to be in the area. Diversity is an important thing in a lot of ways, be it economic diversity or social diversity, and obviously ethnic diversity.

Pearce Vazquez, resident and real estate agent: Fishtown could absolutely use more diversity. I’m Puerto Rican, I would identify as brown, and my two boys are at Adaire elementary school. Adaire, I believe, is around 79 percent white currently.

bonkosi Horn: My husband is black, and I’m biracial. When we first moved here in 2011, if we walked down the street and saw one person of color, it was like, “Oh my gosh! Look at that! There’s someone else who looks like us!” Now, I probably see maybe three times as many people of color in a day as I used to. But my kid is the only kid of color in his class. But honestly, I don’t know that I’d live anywhere else in Philadelphia. I definitely think Fishtown is still a hot spot, at least in terms of evening life — dinner, drinks, entertainment — and I think we’re waiting on it being an around-the-clock hot spot. I think this all comes with diversifying the corridor, in terms of people and businesses.

Tim Pangburn: What excites me more than anything is how they’ve been trying to bridge the gaps between the blocks that are a little bit busier. When you’re bridging those gaps, it’s not like we have a little pocket of business; it’s like this is a district, you know?

Carmichael: Fishtown, come on. We do shit well. Like, you think you know pizza? Fuck it. Try that one. You think a cold latte is good? Hey, try that one. You think Lebanese food is pretty good? Well, try that. We have these levels of things that make you realize that nothing you’re doing is finished.

josh Olivo: At the end of the day, I think it matters less what the neighborhood looks like or what buildings are left standing as long as you have the right community. And that’s going to be folks that have been there for their whole life working together with folks that have moved there recently.

cass Sparks: Sixty-one years ago, I paid $4,200 for this house. And I know today I can get $350,000. But most of us people say, “The only way I’m leaving here is when Marty Burns gets me.” He’s the funeral director.

maggie O’Brien: Ready for this? It was always St. Laurentius School here. Now it’s been chosen by the archdiocese to be a STREAM school — science, technology, religion, engineering, art, math. So now the name of the school is St. Laurentius Catholic School of the Arts & Sciences. Which to me is fantastic and pretty funny, because now it’s fitting in with the new Fishtown. Of course there’s going to be art! Everybody here is an artist! I think that’s a symbol of this neighborhood and people hanging on. We’re not all fleeing; we’re embracing it. So if we have to change a little bit, all right. We’ll adapt. And now the fields are fixed and people no longer mistake our field for a parking lot, and now nobody says, “Ew, you’re from Fishtown.” Now they say, “Oh! You’re from Fishtown? What’s the best place to eat there?”

Sparks: And I can’t say anything else except it’s a really nice neighborhood, always was, and I think it always will be.

Published as “Fishtown: An Oral History (So Far)” in the December 2019 issue of Philadelphia magazine.