From CAPA to Motown Philly: How One Philadelphia High School Made Boyz II Men

On the 40th anniversary of their formation, we look back at how the group went from being just four friends to the best-selling R&B group of all time.

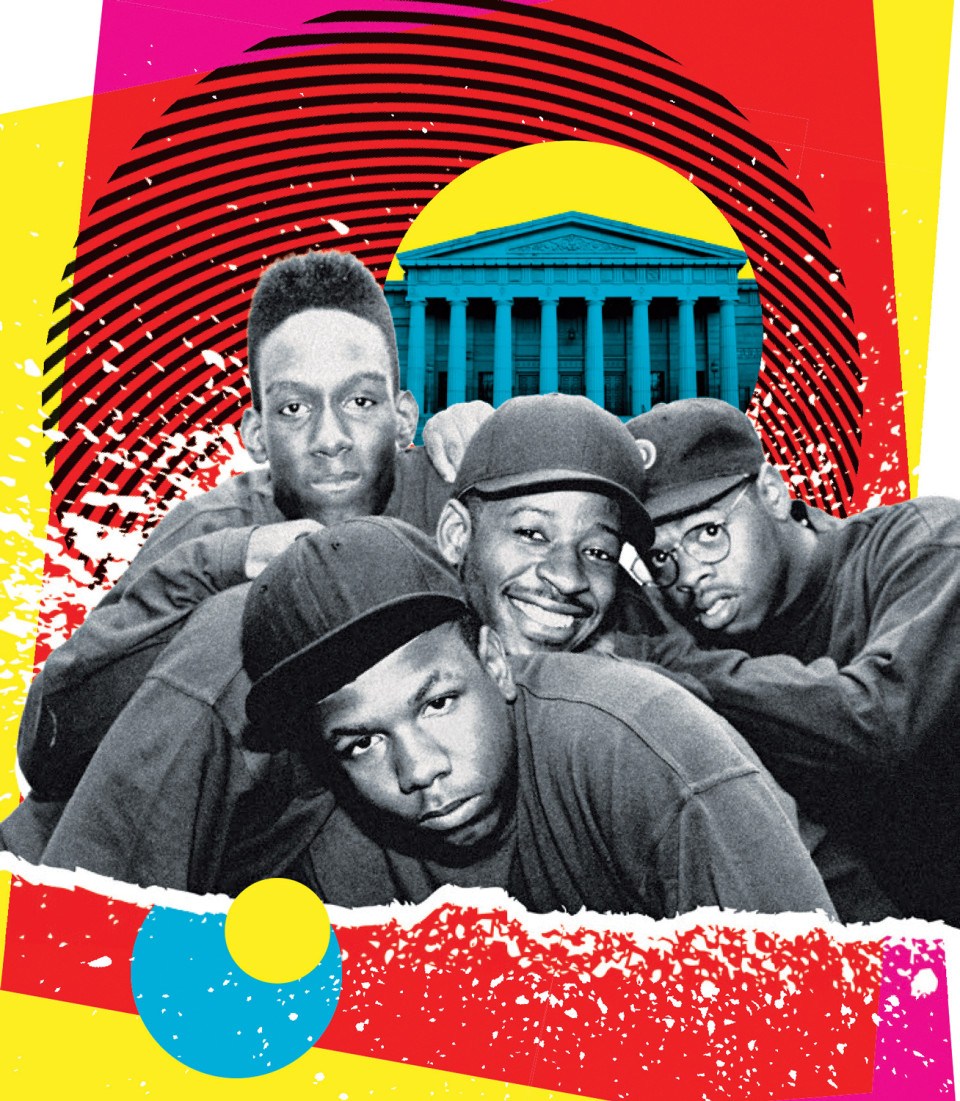

Boyz II Men / Illustration by Leticia R. Albano; photograph by Al Pereira/Getty Images

The following is an excerpt from the upcoming book Boyz II Men 40th Anniversary Celebration, which chronicles the group’s ascent from Philly teenagers to Grammy Award-winning megastars. The book will be released on May 20th.

Boyz II Men as the world came to know them started in 1989, but the group’s origins go back a little further, to a group called Unique Attraction. Formed in 1985 at the High School for Creative and Performing Arts in South Philly, Unique Attraction was both the precursor to Boyz II Men and their original incarnation. The story goes that one day Nathan Morris was singing in class, when his teacher ordered him to stop. Instead of stopping, Nathan sang even louder and was joined by his classmate Marc Nelson. Their teacher kicked both boys out of class and they became fast friends, bonding over a shared love of New Edition. Nathan and Marc then recruited George Baldi, Jon Shoats, and Marguerite Walker into the group. In 1987, freshman Wanyá Morris joined the group, but in 1988, Walker, Baldi, and Shoats graduated and left CAPA. School choir member Shawn Stockman joined the group next, with Michael McCary then joining as the fifth and final piece.

In the fall of 1977, a Philadelphia teacher and administrator named John R. Vannoni had a vision for a new school and a unique educational opportunity for high schoolers in the city. A lover of jazz and classical music and English and American literature, Vannoni’s life revolved around both education and the arts. Vannoni was also a Philadelphia native who graduated from South Philadelphia High School in 1944, before enlisting in the Navy less than a year before the end of World War II. When the former aircraft gunner returned home from the war, he earned his bachelor’s in education from West Chester University before earning a master’s degree in English from Temple University. While working as the head of the English department at Benjamin Franklin High, Vannoni was selected by the Board of Education to be the first principal of the Philadelphia High School for Creative and Performing Arts.

In sharp contrast to other Philadelphia district schools, CAPA was billed as “the district’s first effort at voluntary desegregation” by a Philadelphia Daily News article in December 1977. Like many Northern cities, Philadelphia and its school system still struggled under a form of de facto segregation over two decades after the Supreme Court’s landmark Brown v. the Board of Education ruling outlawed the practice in schools. In the years following the federal ruling mandating the desegregation of schools, education in the United States remained an apartheid institution. In Philadelphia, famous grassroots struggles to integrate schools like Girard College in North Philly raged on throughout the 1950s and much of the 1960s. Mandatory busing was the predominant method of desegregating schools in the city. Often initiated by court order or school board mandate, mandatory busing sought to diversify the racial makeup of schools by sending students to schools outside their communities.

CAPA was different. The school allowed parents and students from around the city to apply freely regardless of their racial background or location. CAPA would be the first Philadelphia school to openly enroll students of all races and structure their educational experience around the arts. CAPA was set to enroll 300 students from around the area and open on February 1, 1978. Vannoni had only been appointed as the school’s founding principal on December 19, 1977, meaning he had roughly two months to assemble a staff and build a curriculum for the school. He cherry-picked a cadre of talented teachers he’d worked with in the past and immediately set about the task of creating the new school.

In the original location at Broad and Spruce streets, those early days of CAPA found Vannoni and his staff flying by the seat of their pants. With classes concentrated into various artistic disciplines, students interested in music, drama, sculpture, dance, painting, and more were encouraged to apply and receive an arts-centered education unlike any in the city. The school also offered creative writing courses and a standard academic program. The classes were often divided by chalkboards instead of proper walls, but the dedicated staff and the ambitious vision that birthed the school ensured its eventual success. Vannoni opted to hire teachers who were passionate about the arts, bypassing the typical method of hiring teachers with seniority, which brought objections from the Philadelphia Federation of Teachers union. But in a Philadelphia Daily News piece from January 1978, Vannoni’s priorities are laid out clearly: “Vannoni wants an entire staff with a heightened sensitivity to the arts. He wants English teachers who can supplement the creative writing courses, math teachers who dabble in photography. ‘Someone who wants to transfer here because it’s a convenient Center City location — that does nothing for our program,’ he said.”

With this kind of careful and thoughtful intention as part of its founding, it’s no surprise that the Philadelphia High School for Creative and Performing Arts has grown into one of the cornerstones of Philadelphia public education and the city’s music scene. In the 47 years since it was founded, CAPA has nurtured several gifted and notable artists, including Jazmine Sullivan, actor/singer Leslie Odom Jr., jazz giants Christian McBride and Joey DeFrancesco, and Boyz II Men classmates Tariq “Black Thought” Trotter and Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson of legendary Philly hip-hop band the Roots.

By the time Nate, Wanyá, Shawn, and Michael got to CAPA, the school’s hallways and classrooms were rich with music and art. In his 2013 book, Mo’ Meta Blues: The World According to Questlove, Thompson described the wildly diverse and creative scene at CAPA in the 1980s. “The first few days at CAPA redefined ‘culture shock’ for me,” he wrote. “I went from a small school of 20 to a school of 2,000, and the first day alone was surreal. It’s like I had been transported into the movie Fame. Look, there’s a knot of goth kids. There are some ballerinas over there in the corner. There are jazz students with their instruments out in the lunchroom.”

CAPA proved to be a perfect situation for Nathan, Shawn, Michael, and Wanyá. With Michael hailing from Logan, Wanyá coming from North Philly, Nate from South Philly, and Shawn from Southwest Philly, CAPA — and its open enrollment policy — was the variable that would ultimately bring them together. The four core members were gifted singers who used music as a means of escaping the harsh realities of life in their neighborhoods. Shawn was the product of a large family. His parents, JoAnn Stockman and Thurman Sanders, raised 10 children in their household, eight boys and two girls. Naturally, money was tight, but Shawn has spoken fondly of his childhood and the joy that music brought him. In an interview for Us II You, the group’s 1995 memoir, Shawn recalled his mother’s musical tastes as an important inspiration in his childhood. “My mother listened to old Teddy Pendergrass albums, LTD, Ohio Players, Michael Jackson, and Stevie Wonder,” he said. “She loved Barry White and loves him to this day.”

We would not have met if we hadn’t attended CAPA. In the neighborhoods we came from, it was not customary to listen to Bach or Beethoven.” — Shawn Stockman

Wanyá came from a much smaller family, with just one brother and two sisters, but initially found a large extended family in the form of his neighbors in North Philly’s Richard Allen Homes. “We are all from urban neighborhoods in Philly,” he said in Us II You. “These were loving communities that turned a corner during our lifetimes. As we grew up, the neighborhoods grew worse. Bad things happened all around us. Gangs and drugs were on the rise. Drugs were available, drugs were as available as a pack of cigarettes. I sat there and I watched a lot of things happen.”

Like his bandmates, Michael grew up in a rough neighborhood and gravitated to music at a young age. He had two brothers and a sister, and his family was a key influence on his musical tastes, playing records and the radio constantly in the house. Michael enjoyed classic vocal groups like the Temptations and contemporary groups like New Edition equally. Meanwhile, Nathan was the youngest of Gail Harris and Alphonso Morris Sr.’s four children. When he was growing up in South Philly, Nathan’s family struggled to make ends meet, sometimes going without basic utilities like electricity, water, and gas. But Nathan was naturally musical and a gifted singer and trumpet player, the perfect candidate to audition and enroll at CAPA.

CAPA not only offered the boys an opportunity to develop their craft through practice, but it also helped open their musical palettes, exposing them to a variety of music that they were previously unfamiliar with. In a 2006 interview with Black Voice News, Shawn explained how those CAPA years affected the group, saying, “We would not have met if we hadn’t attended CAPA. In the neighborhoods we came from, it was not customary to listen to Bach or Beethoven.”

A key part of the young men’s musical evolution during this time was their choir teacher, David J. King. In addition to his work at CAPA, King was a member of the American Guild of Organists, and his musical prowess was unmatched. In the Black Voice News interview, Shawn remembered King as firm but essential to Boyz II Men’s growth. “Mr. David King taught us everything we know,” he said. “He was tough on us but we know now that it was for a reason.”

The boys’ four years at the school provided them with an environment rife with both music and mischief. Between singing in choir and studying the work of musical greats ranging from Beethoven to James Brown, the boys pulled pranks like mooning people in the hallway and handcuffing unfortunate freshmen in the bathroom. The group also practiced intensely — and fought like brothers.

In the group’s documentary Then II Now, Shawn talked about those early years and the growing pains that came along with them. “It’s because we were group members before we were actual friends,” he said. “At first, we argued every day. If it wasn’t about little trivial things and girls and all this other stuff, it was about something else. During the course of everything, we became closer and now we’re the best of friends.”

The camaraderie built during these years undoubtedly prepared the group for their future as Boyz II Men. But before they adopted that now-famous moniker, the group had to find its legs under another name: Unique Attraction.

“Unique Attraction — ugh, so gross!” said Shawn in a 2021 interview with People, poking fun at Boyz II Men’s original name. “It was such a Philadelphia name. If you grew up in Philadelphia, you know exactly what I’m talking about. It was cheesy, but it was the vibe back then.”

Despite Shawn’s present feelings about the name, Unique Attraction was an important stepping stone in the group’s early history. Whether intentionally or not, Unique Attraction and their very “Philadelphia name” were the latest link in a continuum of Philly rhythm and blues vocal groups that stretched back to at least the mid-20th century. When doo-wop began to take shape as a genre in the 1940s, Black America was in the midst of the mass exodus from the American South now known as the Great Migration.

In the immediate aftermath of slavery’s abolition, life as a free man, woman, or child in the South was no less harsh and arbitrarily cruel for Black folks. While Black workers were no longer confined to the plantation by law, they often found themselves economically coerced into performing the same tasks, on the same land, for the same men they had once called master. Militia-style formations of white men were deputized throughout the South and tasked with enforcing the law, which often meant harassing and arresting Black people for irrational, minor offenses such as assembling after dark or legal vagaries like “idleness.” At the same time, lynching reached its height in the decades immediately following abolition.

It was against this social and political backdrop that the blues formed in the South. These events also initiated the movement of an estimated six million African Americans throughout the country over the next six decades. Black American music culture took root and evolved wherever its practitioners went. The promise of jobs in the industrial sector drew African Americans to urban centers like Chicago, Detroit, New York, and Philadelphia. The cultural fabric of the blues remained with the people who sang it, and the Great Migration spread the music nationwide. The popular Black vocal rhythm and blues that emerged in American cities in the 1940s and ’50s would be called “doo-wop” years after its commercial height and eventual decline.

Doo-wop was a combination of the blues, jazz, and Black church music. A decidedly urban music, doo-wop was the sound of Black Southerners wrestling with the trials of love and loss in the big city. In doo-wop, the lead voice and the accompanying voices around it sounded almost like jazz, in which the lead instrumentalist would take a solo, and the band around them would support the soloist rhythmically and harmonically. Most doo-wop songs were based on the I–V–VI–IV, a chord progression built using the first, fifth, sixth, and fourth chords of a musical scale. Combine the doo-wop chord progression with four- or five-part vocal harmonies and you get a sound that pulled from a variety of other genres but maintained a formula that made it distinct. The genre reached its height in the 1950s and has arguably influenced every form of popular vocal music that followed.

In Philadelphia, the doo-wop sound and the vocal groups that sang it were particularly strong. Throughout the 1950s, Philly groups like the Silhouettes (“Get a Job,” 1957), Lee Andrews and the Hearts (a doo-wop quintet fronted by Questlove’s father, Lee Andrews), and the Turbans (“When You Dance,” 1955) released smash hits that transcended the confines of the region and became major hits nationwide. By the 1960s, the doo-wop craze had all but died, but the spirit of that great vocal tradition lived on in many of the new vocal groups that formed on street corners, in playgrounds, and in clubs throughout the city.

In an interview with Spin, singer and drummer Earl Young of the Trammps and MFSB remembered the club scene in the 1960s as a hotbed for local vocal groups. “Scotty’s on 52nd [Street]. I think it was 52nd and Locust,” he said. “We did a lot of the gigs at the Cadillac Club. A lot of these clubs ain’t around anymore. They’ve been gone. We did the Highline, it’s called the Stinger now [the Stinger Club is located above the legendary Sid Booker’s take-out shrimp and seafood spot].”

Sixties vocal groups like the O’Jays, the Ethics, and the Blue Notes were not only precursors to the storied Philadelphia International Records sound that would follow in the 1970s; many of their members would end up cutting hit records for the Gamble and Huff stable.

As a vocal group, Boyz II Men is a part of this Philly soul music tradition, taking direct inspiration from the music that came before them. In a 2010 interview with the Gainesville Sun, Shawn acknowledged this tradition as a formative influence on the band’s work: “We were fortunate to have that type of music and that type of history at our disposal while we were growing up. If that music wasn’t on the radio, then our parents were playing it at home. You couldn’t help but be influenced by that sound and by Gamble and Huff. It was just something that was in our blood.”

In many ways, Unique Attraction was modeled after the classic Philly vocal groups that placed importance on precise vocal harmonies that could only be produced by tireless practice and intimate communication between singers. In an interview for Us II You, Nate recalled one of the bathroom singing sessions that led Unique Attraction to find the crucial component to the group’s sound: the bass.

“We were sort of organizing a singing group, using different members of the choir,” he remembered. “Finally we had Shawn, Wanyá, a friend named Marc Nelson, and myself together, singing as a group. We hadn’t met Michael yet. One day, the four of us were in the bathroom, practicing in there. The song was ‘Can You Stand the Rain?’ by New Edition. Michael happened to come in and without anyone saying a word, he started singing, adding the bass note. It was what we needed, tied the whole together.”

Something good was going on. We had tough times when we were starting out. We weren’t best friends yet. We had to work on respecting each other, understanding where each one came from. But from the start we had this common ground: the music. The more we sang together, the more we blended.” — Shawn Stockman

With the introduction of Michael’s bass, Unique Attraction had a complete sound, but they still weren’t completely comfortable with their name. New Edition’s 1988 album, Heart Break, had given them a signature song to showcase their talents with “Can You Stand the Rain?” but it would be another song from the album that would provide a proper name for the burgeoning group. “Boys to Men” is Heart Break’s closing salvo. Much like “Motownphilly” would serve as a future mission statement for Nate, Michael, Shawn, and Wanyá at the beginning of their careers, “Boys to Men” served a similar purpose for New Edition at the height of theirs. A dreamy ballad with Johnny Gill’s powerful lead taking center stage, the song’s lyrics speak to the group’s desire to grow up and take command of their careers and lives as men. The growing pains that inevitably come along with childhood stardom have never been easy to navigate. The annals of history and the pages of tabloids worldwide are filled with the tragic stories of gifted youngsters who just could not survive fame and public scrutiny with their health and sanity intact. New Edition famously struggled with this dynamic, and “Boys to Men” is a plea for perseverance as much as it is an ode to maturation.

Replacing the word “to” with the double I Roman numeral, Boyz II Men was born. Nate, Michael, Shawn, Wanyá, and Marc then set about making a name for themselves as a quintet. According to Shawn, the first time Boyz II Men performed in public was in 1988 at the Impulse Club (formerly the Cadillac Club) in North Philly. By all accounts, the performance went well, and the boys blew the unsuspecting crowd away with their vocal skills. In an interview for the 1995 book Us II You, Shawn tells the story of that first performance at Impulse.

“We sang three songs,” Shawn recalled. “‘Can You Stand the Rain?,’ ‘A Thousand Miles Away,’ and ‘What’s Your Name?’ The reaction was whooah. Something good was going on. We had tough times when we were starting out. We weren’t best friends yet. We had to work on respecting each other, understanding where each one came from. But from the start we had this common ground: the music. The more we sang together, the more we blended.”

During this time, Boyz II Men also cut their teeth playing talent shows at NU-TEC (formerly the legendary Uptown Theater in North Philly) and CAPA. At a performing arts school jam-packed with gifted young people eager to show off their skills, CAPA’s talent shows were not just fun; they were serious competition. In a 2014 Huffington Post interview, Black Thought recalled when the Roots faced off against Boyz II Men at one of CAPA’s notoriously competitive talent shows.

“The talent shows were, like, huge, man,” Black Thought related. “The production was an annual thing. They would call it Sentimental Journey. So, you know, it was all about who was performing at Sentimental Journey this year. Our rivals wound up being Boyz II Men.”

“They used to cheat with glitter,” Questlove added in the article. “Girls would start swooning. They would have glitter and the top hats.”

While honing their presentation and vocal skills, Boyz II Men began plotting a way to get a foot into the proverbial door of the record industry. While Philadelphia has always been rich with talent, no major music industry infrastructure exists here. None of the major labels or talent agencies have offices in Philly, and in the pre-internet 1980s and early ’90s, this lack of industry institutions was a serious hindrance to the growth of local acts. Many talented locals found themselves hitting a glass ceiling in Philly, and many opted to move to more prominent industry centers like New York or Los Angeles. But Boyz II Men didn’t do that. Instead of going to the places where the record industry existed, they simply waited for the industry to come to them.

Published as “Motown Philly, Back Again” in the April 2025 issue of Philadelphia magazine.