Krasner vs. Dugan: Inside the District Attorney Race That Will Define Philly’s Future

Former Municipal Court judge Pat Dugan thinks he has what it takes to take Larry Krasner down in May’s primary, if he can figure out one thing: What does Philadelphia even want from its district attorney? Or, even more important, what does it need?

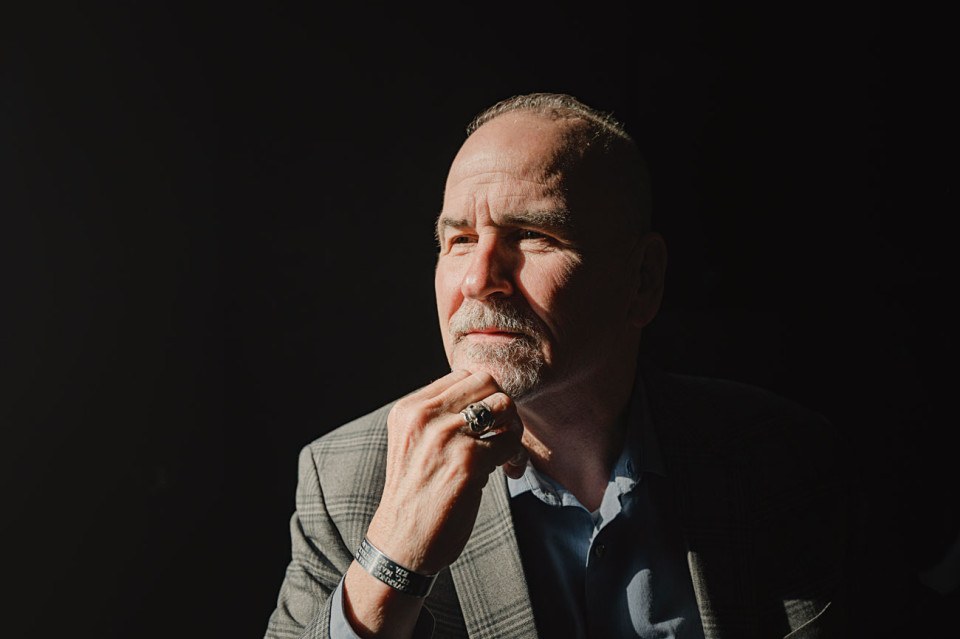

Pat Dugan, Larry Krasner’s challenger in Philadelphia’s upcoming District Attorney primary. / Photograph by Hannah Yoon

Pat Dugan couldn’t take any more from Larry Krasner.

It was during the COVID-19 pandemic, in 2021, at a meeting in the Municipal Services Building with the police commissioner, judges, magistrates, and other stakeholders in Philadelphia’s criminal justice system; Mayor Jim Kenney was there via Zoom. There had been a lot of meetings, some of them about initiatives — diversion programs — that Dugan, president judge of the city’s Municipal Court, held near and dear and that Krasner, the district attorney, would not support.

Dawn Court, for example, which was designed to help sex workers get treatment for addiction or mental health problems, rather than incarcerate them. And no matter how much Dugan assured Krasner that he had no interest in putting sex workers in prison — that arresting them and getting them into treatment was the best way to help them — Krasner wouldn’t budge. He said he didn’t believe in forced treatment. How, then, do you propose we help them? Dugan wondered. Krasner wouldn’t say, and Dawn Court, Dugan says, was abolished.

And courts set up in city neighborhoods for nonviolent, first-time offenders, where they could perform community service or get treatment, then have their records expunged. Krasner, says another Municipal Court judge, “Let that program die on the vine.” Dugan had no idea why.

Ignoring or gutting these programs — including Veterans Court, which Dugan, who had served several stints in the military himself, had started — despite their success and national recognition … why? It made no sense.

Krasner had won election as DA in 2017 as a change agent to an office that needed to be revamped, at a time when progressive DAs were getting voted in across the country. And when he was elected, Dugan, a middle-of-the-road Democrat, was excited. But his view quickly flipped.

“I thought he was going to put all these diversion programs on steroids as a progressive DA,” he says, “but they’ve all been gutted because of his leadership. And it seems like he did it on purpose. It seems like he wants anarchy.” In fact, Dugan and others in the city’s judicial system point to myriad problems under Krasner: an utterly disorganized office, poor training of assistant DAs, and lack of prosecution of both low-level and violent crimes, all of which, they believe, made daily life in the city less safe.

And views of Krasner himself are harsh. Krasner is, according to many who try to work with him, much like Donald Trump; when they say it, they always laugh, because how strange it is that someone so far removed from the president politically resembles him: cocksure, narcissistic, never wrong. And vindictive. But Dugan is certainly not amused. “Krasner is destroying the city through the court system,” he says.

Back to that 2021 meeting, which was on bail reform. It’s a tricky issue, striking a balance between public safety and fairness to alleged offenders. Dugan admits being slow to the problem, how cash bail often holds impoverished, low-level offenders in jail far too long awaiting trial. But now, after taking seminars on the subject, he was on board. Dugan says the judicial stakeholders at the meeting were in general agreement that about 10 percent of those arrested pose an immediate danger and need to be kept off the streets; how to handle them would be the center of the discussion.

But, Dugan says, Krasner wasn’t interested in a discussion, in coming to a memorandum of understanding. This issue was his baby, eliminating cash bail one of the levers of change he had run on, and now he wouldn’t join in, he wouldn’t work with them, he wouldn’t negotiate. In fact, he’d taken bail reform to an absurd place, because he’d begun asking magistrates to set bail at $999,999 for some offenses, such as a car theft, that clearly didn’t warrant anywhere near that amount. It would never fly. Which seemed to be Krasner’s point, or part of some game he was playing — he’d gotten criticized for putting the city at risk, for letting dangerous perps back out on the street too fast, and now he was poking a stick in the eye of the process, overcorrecting to an extreme: You want bail? I’ll give you bail.

Dugan had had enough. Larry Krasner was sitting across from him, five feet away, stern and unreachable. Dugan stared at him and said, “You’re talking out of both sides of your mouth.”

No one at the meeting said a word. Mayor Kenney, from the distance of Zoom, his own relationship with Krasner fraught, was silent. Krasner stared at Dugan. Dugan stared back.

With that, the DA and the judge, for all intents and purposes, were done. Dugan had reached the point where he could barely stand being in the same room with Krasner.

Three years passed. And then Dugan had a come-to-Jesus moment, realizing he had to do something as, in his view, Krasner continued making a mess of the city’s criminal justice system.

Dugan resigned from the bench — a job he still loved, after 18 years — to announce in January that he was running against Krasner in May’s district attorney primary. He’s a long shot — local political observers believe Krasner still has strong support for his agenda among Blacks and white progressives. Plus Dugan is not well known even among the low percentage of voters who will turn out for a DA’s race, and incumbents for city offices below mayor are tough to beat.

But in one way he’s already won. Because in taking Larry Krasner on, Pat Dugan has opened the Pandora’s box of his seven-year run as district attorney.

A great deal was at stake as Krasner became DA in January 2018. The push to end mass incarceration of Black men, especially, was building. (As of 2015, Philadelphia had the highest incarceration rate of the country’s 10 biggest cities, according to the New Yorker.) The DA’s office was reeling from Seth Williams’s imprisonment for accepting bribes and the death-penalty obsession of Lynne Abraham, his predecessor. (Not that those sentences stuck: Of the 200 death sentences imposed in Philadelphia since 1974, almost 150 have been overturned, often because of either prosecutorial overreach or poor representation, according to the New Yorker. Krasner would create a robust Conviction Integrity Unit to investigate questionable convictions.)

Krasner had a particular focus on policing: As a private defense lawyer in Philly, he had sued the police force more than 75 times; when he was running for DA, Krasner called the police union “frankly racist and white-dominated,” noting that the union had endorsed Trump for president in 2016, when he got 15 percent of the city’s vote. Krasner took office as if he were staring straight at Frank Rizzo’s statue across from City Hall with a message: “It’s over.” (Rizzo’s statue would, indeed, come down in 2020.)

It was quintessential man meets moment, and no matter how the political winds blow, it’s hard to imagine the city turning back to anything resembling the bad old days, which is something of a testament to the demand for change that Krasner brought. Michael Coard, whose private practice has been built, as Krasner’s was, on defending the unfairly prosecuted, has called him “the Blackest white guy I know.” When he was first elected, there were, you might say, all good things before him — if he could handle his mandate and the inevitable pushback that would come.

Philadelphia district attorney Larry Krasner at a 2024 news conference / Photograph by Matt Rourke/Associated Press

Krasner grew up in the Philly suburbs and studied Spanish at the University of Chicago. His options, as he considered them, seemed rich: grad school to become a language professor, divinity school (his mother had been an evangelistic minister), or law school. He studied law at Stanford, and there’s a telling moment near the beginning of Philly DA, the PBS documentary series about his early days in office, that explains something of what he would do with the degree.

In the documentary, Krasner remembers his father, a writer of steamy detective paperbacks who suffered from severe arthritis and became wheelchair-bound. Krasner says his father was bullied, or was seen as someone to be pitied. “I think to some extent I’ve had a chip on my shoulder since I was young,” he says. “I saw [my father] treated with disrespect. I didn’t like it. I was really not a fan of bullies.”

In his office near City Hall, Krasner, who sported a ponytail until he was 40, is well coiffed, with a knowing half smile; at 64, he could pass for a Republican senator. When I bring up the documentary, Krasner pooh-poohs my attempt — I will learn he is allergic to self-analysis — but then, as if the truth is bubbling right there: “You’re treated like shit when you’re broke. We were living off SSDI after he was disabled; he’s in a wheelchair for 25 years. He had no hips at all because when the joints failed, he contracted osteomyelitis, so they couldn’t put new ones in.”

A nerve struck — I’ve touched Krasner’s fire when it comes to bullies. I think, then, of how he portrayed the city’s prosecutorial mindset as he was running for this job: that they’d bully their way toward a conviction as if the truth need not get in the way. Yet prosecutors talk about Krasner’s own style as a private defender of the aggrieved, tapping an equal lust to win: “When he talks about prosecutors being underhanded, not being candid,” says one longtime prosecutor who faced off many times against Krasner in court, “all he’s doing is projecting onto others exactly who he is. He fucking cheated and he lied.”

Of course, as Krasner sees it, his aggression is righteous, borne of fighting the good fight. And Dugan himself says he admired how hard Krasner would push as Dugan presided over preliminary hearings with Krasner the defense attorney, “as if every case was the most important in the world.”

Dugan has a decidedly different story. He’s a city kid who grew up in Fairmount and the Northeast; he says he’s 99 percent Irish. His father was pretty much out of the picture from the time Pat was a baby; his mother raised five kids by herself. I first met Dugan two decades ago when he wrote an essay for this magazine, and he answers the nominal question “How are you?” with “Living the dream.” He usually seems both a tad weary and amused. Especially amused. He’s now 64.

“One of the things I think about my mom all the time is how she would just step up,” Dugan says. “No matter what the situation was, if it was called for.”

Pat Dugan after the 1977 Catholic League football championship game / Photograph courtesy of Pat Dugan

There’s a seminal story he tells, about living in Fairmount in the ’60s, with racial tension rampant all over the city: “One evening, there was a young Black kid riding a bike coming down the street, and he was being chased by the older kids in the neighborhood and other kids at the end of the street — one of the guys picked up one of the yellow barricades the police had set up [to control movement on the street], and he knocked this kid off the bike. And they started swarming on him. Now, I’m seven or eight years old — my mother jumps off the stoop, runs down, and grabs these kids. When I say these kids, they were teenagers. She grabbed a couple by the hair, pulled them off this kid.

“She told them, ‘Get away from him,’ and brought that kid over to the steps and sat him with us. We brought his bike over, and someone flagged down a cop.

“That was my mother. And that’s why I’m not afraid to get involved with things.”

Dugan got into St. Joe’s Prep — a nun at his Northeast school paid the $10 fee for him to take the entrance exam — and played center on one of the best Prep football teams ever, then took a slow trek through odd jobs, spent a few years in the military, got a bachelor’s degree, and eventually made his way to law school at Rutgers in Camden.

Then, in 2003, at 43, he reenlisted to go to Iraq, because he had to take part in our war there. After getting out of the military in ’89, he’d watched with some level of guilt as his fellow paratroopers took part in ousting dictator Manuel Noriega of Panama in early 1990; then he missed Desert Storm in ’91. Through the ’90s, Dugan built his career as a lawyer in private practice, focusing on child advocacy. “But when 9/11 happened, that was the moment of I’ve got to get back in. It became a mission of mine because I was tired of watching others who might not have had the training I had as a paratrooper. It was time to get off my couch.”

He describes himself in Iraq as “the driver with the weapon, the body armor, and the Hawaiian shirt”; he worked as a liaison between the U.S. State Department and military and local governments, and with individual groups to set up small businesses. But it wasn’t a behind-the-scenes gig — he was often in harm’s way, driving through gnarly areas with a machine gun or in a Humvee. Many fellow volunteers and soldiers he got to know in Iraq were killed. (The piece he wrote for this magazine in 2006 was about his time there.)

Dugan came home from Iraq in 2004; then, in 2006, he signed up for a tour in Afghanistan.

But his view of the U.S. forays into Iraq and Afghanistan has changed. “I truly believed — and I still believe it on some level — that we go into other countries not to be conquerors, but we go to be liberators,” Dugan says. “But to think that we could actually change cultures that have been the same for a couple thousand years was just, shall we say, more than stupid on our part without having other dominoes fall.” Really, his understanding that our invasion of Iraq was based on lies about weapons of mass destruction began by the time he was in Afghanistan, reading Fiasco, by Thomas Ricks, late at night by flashlight, just trying to fall asleep; it was about the Bush-Cheney collaboration, “the bill of goods we sell our 18- and 19-year-old kids who are running around with a flag saying, Yeah, let’s go do it!”

Pat Dugan in Iraq in 2004 / Photograph courtesy of Pat Dugan

After his return from Afghanistan, Dugan was appointed by Governor Ed Rendell in 2007 to fill a vacant seat on the Municipal Court and then elected two years later. The best part of his time on the bench, Dugan says, was getting people with, say, a drug problem treatment through diversion programs like Veterans Court rather than locking them up: “You saved my life,” they’d tell him later. “I now have my children back. I have a full-time job. My parents speak to me.” Veterans Court attracted judicial observers from all over the country — though now it’s been largely eviscerated, Dugan says, because of Krasner’s decision not to charge low-level offenders as a way to offer them help.

Half a dozen court insiders tell me the same thing about Dugan as a judge: that he was even-handed, fair, measured, not leaning one way or the other. He’s not an ideologue.

When I ask Dugan what drove him to run against Krasner, certainly an extreme gambit given the odds of winning, he says, “I think the one that really hit me was Kensington Avenue. Since I’m a city kid, I know all about the El. I was riding out there when I was eight years old with my brother, who was nine. We would go down to the Midway Theater on Allegheny, right at Kensington. And we would go shopping down on Kensington Avenue. Or I would play football under the El with my friend Red Dog.”

The demise of Kensington — an area that became, over the past few decades, the biggest open-air drug market on the East Coast — is personal to Dugan.

“People in the community were begging for help to everybody — the mayor and City Council, the police department. And they all said yes, we want to help you. We want to do this. But if the district attorney’s not going to charge anybody, it’s not going to work.” He’s not talking about a disagreement over policy, though, so much as the horror he learned about: “Addicts shooting up in public along the streets where the kids have to walk to school, parents saying, ‘My child can’t walk to school safely in the morning.’ And Krasner was pretty much the sole obstruction to really moving forward with any type of community court” — to get addicts off the street and into treatment. “He just would never buy into it.”

“This accusation is completely nonsensical,” Krasner says. “There is absolutely no truth in this.” (Mayor Cherelle Parker established a community court in Kensington in late January.)

Dugan thought that, over time, Krasner would be pushed politically to deal with problems like Kensington. He kept waiting, and watching, as his frustration over what was happening in his city grew.

The story of Larry Krasner arriving in 2018 to upend a criminal justice system in bad need of an overhaul has a counter-narrative: Some good things have been lost on his watch. In his first term as DA, Seth Williams implemented a program known as zone prosecution. The police department is divided into six detective divisions. The program assigned prosecutors and judges to individual divisions so that they would get to know the area and its residents, and would be able to share information to get the most dangerous criminals, the subset willing to carry loaded guns and use them, off the streets.

It worked like this: A guy gets pulled over by a cop for, say, a broken taillight, and reveals that he has a gun in his car. He owns it legally, but gets arrested for possessing a handgun without a license to carry, which will likely get him probation. Here’s where it could get interesting — his profile is put through Gun Stat, which has gun-crime info collected by police on prior arrests, and cops share intel they’ve dug out with the assistant DA who has the case. Maybe the cops have informants who told them about this guy’s gang involvement and drug dealing. Perhaps his social media profile shows him bragging about his followers, how he owns them. His lawyer might try arguing that his prior arrests were for low-level stuff, nothing consequential, but the ADA shares with the judge what he’s learned and pushes for a state sentence for this gun possession charge so that the guy will not only be off the street for a while, but held where his communication can be monitored (all calls from prison are recorded), exposing whatever he’s trying to direct while incarcerated.

When Krasner became DA, he wiped out zone prosecution. A former prosecutor who explains how it worked believes that was a terrible decision: “The first couple of years after he came in, shootings skyrocketed. Because the shooters were no longer getting effectively prosecuted.” He’s right: The murder rate in Philadelphia did go through the roof, though cause and effect is tough to nail down in crime trends. Yet we do know that under Krasner, the average annual rate of gun-homicide dismissals and withdrawals increased 75 percent, and the average annual rate of non-fatal shooting dismissals and withdrawals went up 39 percent. (Those numbers are skewed somewhat by the challenge of running courts during a pandemic.) Still, Krasner should get credit for his pursuit of nonviolent gun cases: His office is prosecuting twice as many of them as Seth Williams did.

“I heard from victims’ advocates and the police department throughout the system,” Dugan says, “and they just didn’t understand why Krasner didn’t want to listen to anybody about how valuable zone prosecution was.”

The DA has said in the past that he did away with the initiative because it “often siloed the prosecutors and led to biased evaluation of subordinates.” And certainly Krasner was not going to stick with a program that allowed prosecutors and cops and judges to put their heads together in pursuit of the worst offenders, not when the collaboration of the most aggressive players in the system was exactly what created the abuses he’d come in to stop (starting with, in the example above, why the driver with a gun in his car had been pulled over to begin with). It was, to put it in simple terms, a choice between fairness and safety; Krasner would take his chances on undercutting the latter. And on the fairness side, Krasner was trying to reduce sentences, not hold convicts longer.

Dugan cites this, too, as part of Krasner’s thinking: “It wasn’t his idea. It was somebody else’s.” Which goes back to Dugan’s frustration with him out of the chute, how Krasner had so little interest in the successful diversion programs Dugan wanted him to get behind. Krasner did come up with some diversion programs himself, run out of his office — for mental health problems, for people under 25 who’d been charged with low-level crimes, and his own version of steering low-level offenders into community service or a treatment program instead of prison. In fact, Krasner claims that diversion expansion and improvement is one of his “signature achievements,” even as the percentage of cases diverted dropped from 13 percent under Seth Williams to 3.5 percent the past four years. (The pandemic likely played a role in those numbers.) And his lack of interest in working with others is a ubiquitous complaint, as if he cares about the answers only if they are his. Which raises a couple of questions: Is he really that petty? Or power hungry?

When Krasner started, he fired 31 prosecutors immediately, forcing them to come in on a snow day in January 2018 to pack up their offices. “Some of them may be absolutely great, hardworking attorneys who just believe that too much incarceration is not enough, and they’re not capable of following orders,” he told the New Yorker, “and they’re always going to be undermining you. You’ve got to show them the door.”

But many observers believe the firings were more personal than that. Retired Court of Common Pleas judge Ben Lerner once ran the public defender’s office in Philadelphia, and he hired Krasner 38 years ago. (“So I got this whole thing with Krasner in Philadelphia started,” he jokes.) Lerner believes that many of the 31 firings, of longtime prosecutors whom Lerner and others regard highly, were vindictive: “Most of the people on the firing list he had personal problems with” — stemming from Krasner’s time facing them as a defense attorney — “or in a couple cases, with his wife, rather than a failure to do their job.” (Krasner’s wife, Lisa Rau, was a Common Pleas judge from 2001 until 2019.)

At any rate, Krasner had gutted the office of many of his most experienced prosecutors, and from that moment forward he was playing catch-up just trying to get it to run, according to new prosecutors he brought in who later left in frustration. He recruited nationwide, at Stanford, at the University of Michigan, and at other top schools, shifting away from the longtime practice of recruiting locally. But during Krasner’s first term, about 70 new hires quit, and overall, 261 out of an office total of about 340 prosecutors would leave, according to the Inquirer.

Some of the new hires complained that instead of being trained how to win cases, they were indoctrinated with the abuses of the criminal justice system.

Early on, Krasner asked new recruits if they had read The New Jim Crow by Michelle Alexander, which analyzes mass incarceration; they would learn that there were more people of color incarcerated now than were enslaved at the outbreak of the Civil War. Whenever a prosecutor was trying to send someone to prison, he had to state how much that cost per year — at least $42,000 when Krasner became DA — and spend a moment on the “unique benefits” for prisoner and society. No wonder, then, as a former prosecutor tells me, that “some new DAs were literally in tears when they had to ask for jail time for people because they were completely unprepared to do it.”

The lack of training of assistant DAs continues to pop up in court in myriad ways. Dugan would sometimes stop prosecutors in their tracks in open court by asking if they were in touch with the victims in their cases. If the answer was no, he would ask if they had the victim’s number — if so, Dugan would have them make a phone call, then and there. Attorney Michael Coard, alarmed by young prosecutors’ pregnant pauses when they are surprised by, say, questions from a judge, sometimes takes the lawyers aside post-trial and advises them on how important it is to find a groove of performance, of confidence, to not get caught staring silently down at their paperwork.

It’s a product of turnover and seat-of-the-pants organization, many who have worked in the office say. What’s more, the office is still run, says a supervisor who recently resigned, in an ad hoc way; he says that over the past couple of years, Krasner has created special units to deal with carjackings and gun possessions to appease City Council, which funds the DA’s office. Krasner pulled experienced ADAs out of the Major Trials Unit, which prosecutes violent crime, gunpoint robbery, and drug dealing, to staff these new units, essentially gutting Majors, according to the former supervisor. “So people with less than a year experience are trying rape cases, which is just crazy, and other felonies like armed robberies,” he says. (Krasner claims that Majors was not gutted to support the new units.)

Krasner’s a lone wolf. He once bragged that he often scribbled new initiatives on napkins, and maybe he meant it: Krasner decided early on that retail theft up to $500 would be soft-pedaled. Cops largely stopped responding to it, and retail theft incidents rose by one third from 2020 to 2023. The perception bloomed that it was open season on stores all over the city.

Anti-Krasner sentiment at a 2019 rally / Photograph by Tim Tai/Philadelphia Inquirer/Associated Press

A couple of years ago, a member of City Council was in a bar in Southwest Philly when a guy came in and started taking orders from regulars there — for batteries and shampoo and other stuff that could be grabbed off the shelves of a Rite Aid or Target he was going to hit up. The councilmember invited Krasner to come with him to the bar to see for himself how a black market was being created; the DA declined the invitation. Wawa executives reached out to the state attorney general’s office to complain: “We need some common sense here. Our security guys can’t even stop anybody at the door.”

It was a circular shitstorm of inaction and perception, the nadir of which was the 2023 stabbing murder of a security guard at Macy’s near City Hall by a guy who had tried to steal hats. Finally, Krasner admitted that his retail theft policy wasn’t working: “On reflection, I don’t think it’s the best approach.” He created a task force to deal with it.

All this had been grating on Dugan since 2018, when Krasner started. About a year ago, he reached the point where he had to do something about it: “I actually said in my head and then out loud that if nobody is going to run against this guy, I will. I said it out loud, and I said it to myself quite a few times, and I hoped and prayed that others would get in the race. I had conversations with people, not about if they would support me if I ran. It was more about ‘Are you running? Will you run? Please run.’”

Dugan talked to Councilman Derek Green. And Keir Bradford-Grey, who had been the chief public defender in Philadelphia.

They said no, they weren’t running.

“I was hoping and praying that people would do it, and it never came to fruition,” Dugan says. “And I couldn’t take it any longer. I love this city too much. I really want to make it safer, and hold people more accountable. My mind was already made up that I would do it if no one else stepped up.”

So running became — in the challenge he made to himself — personal too, like the problems in Kensington and other hot spots were. Just in a different way. It was time to get off his couch once again.

As DA, Dugan says, he would start recruiting assistant DAs locally, as they traditionally were, from Temple and Penn and Drexel and Rutgers Camden, to find lawyers invested in the city. He would make people accountable for even petty crimes; make sure, if someone is caught with a gun four or five times, a well-trained ADA is handling his case. He would reinvigorate diversion programs like Dawn Court, and he’d bring back zone prosecution, assigning senior ADAs geographically to partner with police and judges to track the worst criminals.

If he wins. If anything, Donald Trump’s reelection will help Krasner, who as the campaigning began in late February seemed to be running more against the president than against Dugan. But politics makes strange bedfellows, and it seems possible that Elon Musk will throw millions of dollars Dugan’s way, as the lesser evil. Which would allow Dugan to mount the full-scale TV ad campaign he certainly needs.

In Larry Krasner’s office, I ask him if he believes he’s made the city safer.

Krasner quickly calls up murder numbers on his phone, and of course the news on that front is much better, from 562 murders in Philadelphia in 2021 to 269 last year. But that’s the trend in other big cities as well; cause and effect — just like with the claim that losing zone prosecution spiked the murder rate in Philly — is likely due to a raft of things.

Krasner then leans into his passion on incarceration rates as only he would: “I think we are safer and freer, and I think it is very important to note that we are both of those at the same time. That is not unusual. You can look at some countries that have handled criminal justice in the last 50 years much better than the United States, including modern Germany. And you will find that they are also safer and freer. If you want more specifics, Germany, modern Germany, has about 11 percent of our incarceration and about 11 percent of our homicides. All at the same time. And for a very long time.”

I listen for a few minutes but then stop Krasner to run the chorus of negative stuff I’ve been hearing by him, to see how he’ll react:

That a lot of new hires have left throughout his tenure. There’s still high turnover.

That he has a chaotic, disorganized office culture, including manpower used poorly.

That training of ADAs is not up to par. It’s more indoctrination than courtroom specifics on how to run a trial, and there’s insensitivity to victims.

“Let’s start with the first one,” Krasner says evenly. “What was the first one?”

“That a lot of new hires have left throughout your tenure. There’s still high turnover.”

“No, I don’t agree with that at all. I think it is very clear that we have been able to bring in much more talented people. There’s no question about that. We’ve made great efforts to do that. I think it’s very clear that they are better compensated than they ever were before, which has resulted in significantly longer retention.”

Krasner refutes the other points as well, as I expect him to, but what I’m really zeroing in on is him — he’s calm and sure. I tell him something else I’ve been hearing, a personal criticism of him from his own employees: that he is tough to approach. That he always has the answer and doesn’t admit wrongdoing.

“I just have no idea what you’re talking about,” Krasner says.

Perhaps he doesn’t; a high-level prosecutor told me he said to Krasner, after he’d gone to him with complaints about how the office is run and got no satisfaction: “Larry, you use the word ‘hear’ in the most literal way I’ve ever heard. You say that a lot — I hear you. I hear you. Like you literally mean that my voice is reverberating and the airwaves are moving and it’s touching your ear, but it’s not. There’s nothing going into your brain.”

Likewise, Krasner doesn’t seem at all touched by what I’ve run by him; he goes on autopilot, into the parallel world of how he sees his great success as DA, even when I share more personal stuff I’ve heard: that he’s a narcissist, and an anarchist. Krasner brushes those things aside.

The tone changes quickly, though, when Pat Dugan comes up. What seems to trigger Krasner is reminding him that, at a meeting four years ago on setting new terms on bail, Dugan accused him of talking out of both sides of his mouth, as if he was seeking a sort of vengeance: “Nonsense,” Krasner says. “That’s simply not true.”

Krasner tells me that Dugan viewed being president judge of the Municipal Court as a stepping stone, which, he says, was orchestrated by city Democratic Party head Bob Brady (who is about as old-school as you can get). That Dugan ran for Superior Court, and lost, and that Municipal Court is the lower court, where misdemeanors are heard along with preliminary hearings of more serious stuff. “I didn’t hate Dugan, I didn’t love him,” Krasner says. “I was frankly very troubled by his handling of the Josey case.”

With that, Krasner’s going for the jugular.

In 2012, a Philadelphia police lieutenant, Jonathan Josey, was accused of assault for hitting a woman in the face after the Puerto Rican Day Parade; it was captured on video, and Dugan, presiding over his trial, acquitted him.

He was roundly criticized. Dugan clearly should have recused himself from the trial to avoid a conflict of interest, since his wife was then a police officer, but he stands now with the verdict he delivered, that the case was much more complicated than one moment caught on video that went viral.

It’s fair game, of course, for Krasner to delve into Dugan’s track record as a judge. Though what’s most telling is Krasner’s tone of dismissing Dugan as he digs in harder to make sure I get the point of how awful that acquittal was:

“I went looking for that video one more time to make sure my memory had not lapsed. A video of a very large police officer punching a much smaller Puerto Rican woman for what I suppose was the heinous offense of somebody throwing water in the air on a sunny day. I hadn’t seen it in a very long time.” Clearly, this will be a talking point against Dugan during the campaign.

Meanwhile, there are some serious problems at the DA’s office, no matter how much Krasner goes on, as he does now, about how great his tenure has been and how small Dugan is. The guy who wants to blow up the system has an adversary, one who merely wants to fix it, and that does not sit well with Krasner.

A question is emerging as we head to the primary: Has Krasner undercut the moment when change in the DA’s office was possible by being the wrong kind of guy to push for something new, by being too disorganized, and cocksure, and downright nasty to get the job done? There’s another, more basic question to consider: How do we balance safety and fairness, which have so often clashed in this city? What, in other words, do we really want our criminal justice system to be?

A few days later, I ask Dugan if he’s ever heard the criticism that Krasner is the progressive version of Donald Trump, in how they are both narcissistic and immune to criticism, and have no interest in playing with others. Also that when push comes to shove, things will get a little … personal.

Dugan doesn’t really want to go there, to bring Trump in, but he smiles — all Irish, impish, a little flushed. He knows what he’s in for, and what he got off his couch to take on.

Published as “The Challenger” in the April 2025 issue of Philadelphia magazine.