Trump’s Federal Spending Cuts Will Destroy Philadelphia’s Science Community

“Shut us down and you can say goodbye to the cure for cancer, Alzheimer’s, Parkinson's, and everything else that matters.” Philadelphia scientists on the Trump administration’s crippling cuts, and how they’ll affect us all.

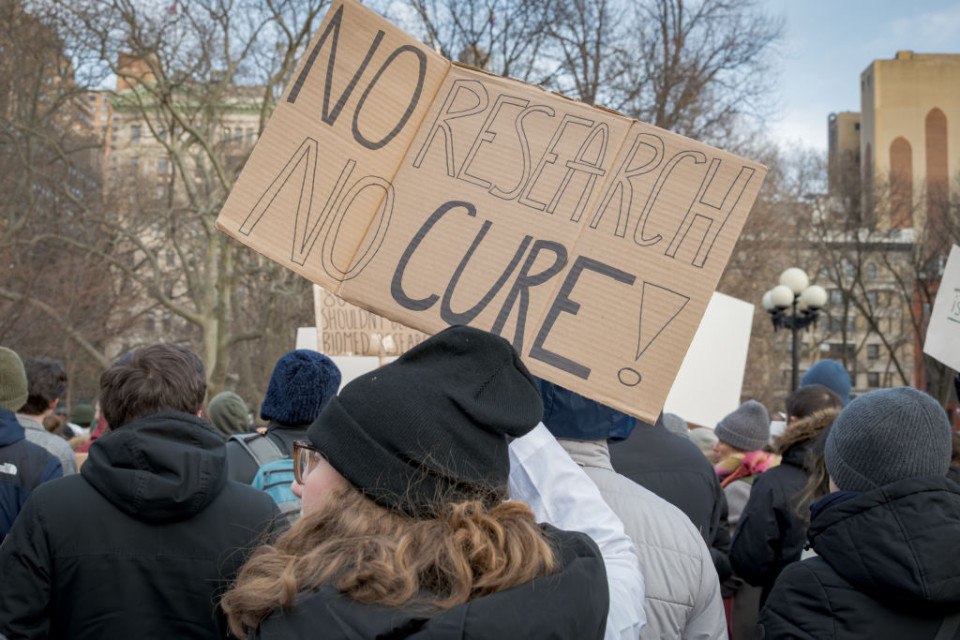

Hundreds of academic workers, elected officials, and allies gathered at Washington Square Park in Manhattan for a protest against the Trump administration and the Department Of Government Efficiency (DOGE) federal funding cuts for science research. / Photography by Erik McGregor/LightRocket via Getty Images

Soon after Donald Trump was inaugurated in January, the U.S. government froze all federal grants, sending folks who rely on those grants scrambling. Research was halted, salaries in limbo, and chaos reigned. We asked Philadelphia-area scientists to weigh in on these cuts, and how they’ll not only affect their livelihoods and research, but all of us.

Every new cure, drug treatment, or vaccine, starts with basic science. To fix something, you have to know how it works in the first place. Basic science teaches us how biology works under everyday circumstances so when something goes wrong — from disease or injury — we can fix it. Basic science is the blueprint for who we are.

As a professor in Center City, my lab studies Alzheimer’s disease. We study the basic science of how the brain works so we can understand how Alzheimer’s “breaks” the brain — and how to fix it. To do this, I have the privilege of working with some of the best minds in the world. We apply for grants from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and if we’re lucky enough to get those grants (trust me, it’s tough) we’re entrusted with valuable taxpayer dollars to do basic science and fix disease.

Recently, the administration froze new NIH funding for basic science and drastically reduced support for research infrastructure. Those funds are not “bloat,” they keep everything — and everyone — working. That money pays for electricity, rent, and the salaries of everyone from scientists to janitors to IT to teachers. Without that money, our ability to do basic science doesn’t just slow down, it stops.

For me, rather than focus on curing Alzheimer’s, I spend my day scrambling just to keep those amazing scientists employed. Without that money, countless hardworking people will lose their jobs. For every $1 the NIH spends on basic science, the American economy gets $2.46. That’s a good return. That money doesn’t just drive cures, it drives the economy, the service industry, housing, small business, you name it! Every corner of Philly benefits from America’s investment in basic science. Without NIH funding, not only do we lose our ability to draft the biological blueprints needed to cure disease, we lose an economic engine that drives what makes Philly incredible. If we lose that, we lose the essence of America. —Tim Mosca, PhD, neuroscientist

The next generation of U.S. technological progress will require individuals trained with the skills needed to make new discoveries. The current delays and uncertainties around the federal support of science are having a disastrous and discouraging impact on smart individuals with tremendous potential who want to pursue graduate education. It’s admissions season for the fall 2025 incoming graduate class, and many graduate programs nationwide are shrinking their programs, including the University of Pennsylvania (where class sizes are being reduced by around a third).

Across these next few years, fewer individuals engaged in research will translate into fewer scientific breakthroughs. In the longer term, if we lose a generation of researchers, those effects will reverberate because the innovators of this generation will be required to train the innovators of the next.

In parallel to this tragic loss of scientific progress and potential, the economic losses to the Philadelphia area will be devastating. For instance, recent changes to the grant support from the National Institutes of Health are projected to result in a loss of $240 million to Penn. Those dollars are earmarked to support “Facilities and Administration.” That includes hundreds of staff required to make biomedical research happen, from custodians to animal care support personnel to individuals in charge of ensuring research adheres to federal guidelines. It’s not just scientists who will lose their jobs; many others will, too. — Nicole Rust, professor, department of psychology, University of Pennsylvania (speaking in a personal capacity)

Protesters react to the Trump administration’s federal funding cuts.

Imagine yourself as a young child, in a world that is new to you. There are things you want (snacks, and cuddles, and songs) but you have no way to express those desires to others. Or imagine that you had very strong skills in one area — like writing — but struggled to get recognition for those skills because of weaknesses in an unrelated area (such as being able to charm an employer at an interview or advocate for yourself in a big meeting).

The above scenarios motivate my research. I study how to identify and diagnose young children with autism as early as possible, so they can benefit from communication-building interventions while their brains are still developing. Children in the U.S. wait two years on average for an autism evaluation, so we urgently need to improve the diagnostic pipeline. I also lead an NIH-funded study to understand how autistic adults experience successful and unsuccessful communication, and how society can best support them so that they live meaningful and self-determined lives.

Over the past several years, my team and I have worked hard to build the infrastructure needed to conduct large-scale scientific studies aimed at improving communication experiences for autistic people. Last year, I submitted two NIH grant applications that would have supported me and a dedicated team of collaborators and trainees over the next five years. They are now indefinitely stalled within the review process. Funding is already tight in disciplines like mine, disciplines which are not easy to monetize. These delays have already reduced the number of staff and trainees I can support, with the knock-on effect of the loss of bright young minds in a field that desperately needs new insights. If funding remains frozen, my research career will likely end altogether.

Financially, I will likely be fine. I can work fewer hours for more pay as a practicing psychologist, while still doing good, important work. But this kind of pivot by clinical scientists has downstream impact; I’m not the only one facing this wrenching reality. These funding freezes hurt autistic people (over two million children and five million adults in the U.S.) who desperately need faster and better care. America has long stood as the global beacon for scientific research, something that has always filled me with immense pride. For the first time I can remember, that beacon is fading, and I fear if things don’t change it will be put out. — Ashley de Marchena, PhD, licensed clinical psychologist

I’m a UPenn faculty biomedical researcher who has been at UPenn in one capacity or another for more than 30 years (I started at postdoc and worked my way up to associate faculty). My lab supports a large number of projects by providing the critical statistical and computational components that all modern biomedical projects rely on. My lab is supported by very few direct costs; the university utilizes indirect costs to fund us, because we are a critical, basic and fundamental component to the whole translational medicine institute. And NIH generally funds such things through indirect rather than direct costs.

If indirects are cut to 15 percent, then with high likelihood I will lose my lab. We are right now on the cusp of important technical advances that promises to significantly impact the analysis of a fundamental data type, thereby facilitating faster routes to the cures we are all waiting for. We are just about the only group working on this right now, so if we are shut down, it will set back the pace of progress in this domain for a long time, possibly permanently.

Because once a lab is shut down, it cannot just pick back up where it left off if funding returns. All labs are in a delicate situation, developing the right talent and getting the right talent working together. This takes years (some labs have been maturing for decades) and often involves so many intangibles that it cannot just be repeated.

These disruptions will cause a permanent scar on the face of biomedical research. And without a doubt many people who support these policies will die sooner than they otherwise would have, because the cures were delayed, possibly indefinitely.

Very few people understand that nearly the entirety of biomedical research is done by academics and funded by the NIH. Just take the RNA vaccine for example. It was invented at UPenn (two Nobel prizes were awarded for that in 2023). It took decades of research to arrive at a marketable product; in all that time NIH funded the research. Only once a product is profitable does industry step in. Industry does clinical trials, production and distribution. That’s the easy part. What research money they do spend is generally dedicated to making copycat drugs or other safe short-term-to-profit research.

All major biomedical advances come from academics. And opposite of what people are told, we are among the most efficient and productive of all workers in society, because academic scientists work on shoestring budgets for modest salaries and have to work 80 hours a week to survive the extremely competitive environment. Only the most productive and efficient survive.

Shut us down and you can say goodbye to the cure for cancer, Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and everything else that matters. All we’ll get from industry will be six or seven more versions of Viagra. It won’t be long before the industry pushes back, because they need academic research and the NIH to survive. Just like Boeing needs the Department of Defense to survive. Just like SpaceX needs NASA to survive. The entirety of the pharmaceutical industry needs academic NIH-funded research. That’s what these guys are destroying. — longtime Penn faculty member (speaking in a personal capacity)

For the first time in my 20-plus-year career, biomedical research has become a topic of intense political pressure. Admittedly, this has been a challenge to wrap my head around. Bipartisan support for biomedical research aligns with my expectations that we all want to live long, healthy lives; we also want this for our parents, our children, our families, and our friends. However, in 2025, that assumption is being challenged by proposed dramatic cuts to research funding at the NIH and elsewhere.

The prospective cuts and dramatic decrease in federal funding for research that has already occurred will have a devastating impact on both rural and urban communities, in red and blue states alike. They will lead to slower development of better treatments for devastating diseases like cancer, mental health conditions, and addiction. Many discoveries that lead to drug development in the pharmaceutical industry come from academia, so the cuts will cause a decrease in the scientific discoveries behind new drugs that would treat any of us suffering from chronic disease.

I am a member of a national consortium, funded by the NIH, working to identify new drugs for Alzheimer’s disease using human genetics. It feels like we are getting so close to identifying those targets; I would hate for us to lose progress when so many are suffering with Alzheimer’s disease today.

Losing funding to do this life-saving work in the United States could push researchers and the research overseas. I would expect that many scientists will move to other countries where they have made broad investments in biomedical research, artificial intelligence, and research infrastructure.

If a significant portion of the U.S. biomedical research enterprise moves abroad, this will weaken the U.S. position as a global leader in scientific discovery and may have impacts on national security. Biotechnology is one of the top technologies that impact the U.S. national security environment, and we need to keep as much biomedical research within our country as possible so that we can defend ourselves against biological weapons along with epidemics and pandemics.

This all feels like an unforced error. I hope for the health of my family and yours that we continue to fund biomedical research and avoid draconian cuts. Our lives depend on it. — Marylyn D. Ritchie, PhD, professor of genetics, University of Pennsylvania’s Perelman School of Medicine. (My opinions do not necessarily represent those of the University of Pennsylvania Health System or the Perelman School of Medicine.)