Steven Singer Loves the Haters

In his first-ever in-depth profile, Philly’s shock-jock jeweler throws open the vault and reveals the guy behind his iconic salesman shtick.

Steven Singer sporting the diamond ring he offered Travis Kelce for free to give to Taylor Swift / Photography by Jonathan Pushnik

“Have you started your story yet?” Dad asks from across the table. My husband and I are out to dinner with my parents, and the topic has swung to my approaching deadline.

“What’s it about?” my mom asks. “The jewelry guy?”

“Singer, right?” says my dad. “The guy with the billboards. ‘I hate Steven Singer’ or something?”

“Why do people hate him?” my mom asks, and then I witness the same conversation that thousands of people have been having ever since Steven Singer’s iconic billboards started mysteriously sprouting up along Philly highways in the early aughts.

“I think it’s because his prices are so low that other jewelers hate him,” my dad explains.

“That’s mean. Does he know about the billboards?” my mom asks.

“Yes, Mom, he knows about the billboards,” I say. “And I haven’t started the story yet.”

“What are you going to say about him?” she asks.

I don’t have an answer for her, because if I’m honest, I have no idea what I’m going to say about Steven Singer. I’ve never been to his eponymous shop on Jewelers’ Row, which he opened in 1980. (His first location was a sliver of a store with only six cases of jewelry and no heat or running water; the current building stretches down half a block of 8th Street.) I’ve never heard him on Howard Stern or WIP or WMMR or any of the myriad radio shows he frequents to promote his business. I don’t even know what the man looks like.

And then, as if he’s somehow heard us, Steven Singer appears behind me. My husband spots him first.

“I think that’s him,” he says, pointing to a television mounted on the wall. The TV is muted in the restaurant, but there’s closed captioning, which is helpful, because otherwise, the commercial that’s on would be quite confusing. Singer is standing in front of a stark white backdrop, wearing a blue suit with a red striped tie. He looks like a politician, or a car salesman, or a lawyer. It’s not until his infamous tagline slides across the screen — I HATE STEVEN SINGER, thick white letters graffitied against black — that it’s clear this is an ad for a jewelry store and not, say, a personal-injury attorney explaining the potential for a mesothelioma payout.

Singer walks across the screen to where two beefy men are arm-wrestling. Text pops up with arrows indicating what the men signify: The guy on the left, with slicked-back hair and a sharp suit, represents “other jewelers”; the one on the right is “their customers.” Singer gestures to the men and explains that jewelers love to haggle — “practically wrestling for the best price” — because it increases their profit margin. He explains how it works: The “other jewelers” take a diamond ring and mark it up massively so you can feel good about negotiating it down to a “too good to be true” deal. You leave thinking you got a great price at 40 percent off when they could have knocked it down by 60 percent. Behind him, the guy in the suit wins — another jeweler taking advantage of an unwitting consumer.

“Crazy, right? Is that how you want to buy a diamond engagement ring?” asks Singer, before explaining how he does business — giving customers the best price at the outset. And then more text pops up: REAL DIAMONDS. REAL JEWELER.

Of course Steven Singer is a real jeweler — a real person — but he’s always seemed to me like something of an urban legend. Everything I know about him is anecdotal, a string of stories that get progressively … weirder.

“I get one of his gold-dipped roses every year from my husband,” says my friend Brittany.

“I heard him on the Howard Stern show the other day, and Stern was singing a song about him,” says my friend Ashley.

“I hid in the bushes with him one time to ambush someone with a surprise proposal for a radio show,” says my friend Carrie, who was the editor of Philly Mag’s wedding magazine at the time.

“I walked by his store once, and it was filled with bubbles, and I think girls in bikinis were wading through it to find, like, prizes?” says my friend Jen.

This is all part of the lore of one of Philly’s most classic characters, a jeweler with a larger-than-life persona who’s been piquing our interest with bullish billboards and risqué, tongue-in-cheek ad campaigns for more than two decades (and selling us jewelry for nearly 50 years). Still, actually seeing him on TV — I don’t watch it a lot — is surprising. I’m not sure what I was expecting. Someone slicker, perhaps. Bigger, brasher, more bombastic, more colorful. But there he is, a man in his late 60s with a neat spray of salt-and-pepper hair and a classic politician suit. So this is the guy, I think. Huh.

The commercial ends, and I turn back around. I’m no longer wondering who hates Steven Singer.

I’m wondering who he is in the first place.

A friend of mine from Connecticut once remarked that Philly’s billboards are overrun by personal-injury lawyers. She’s not wrong. In the 30 or so miles of I-95 South stretching between my house and Center City, I count at least 20 of them, most of which are a jumble of last names linked by hardworking ampersands: Krasno Krasno & Onwudinjo, Morgan & Morgan, Stern & Cohen. I hadn’t taken much notice of them before, but as I drive to Jewelers’ Row one day for a meeting with Steven Singer, I’m riveted.

It’s not all lawyers, though. There are billboards for storage units, smoke shops, beer (“brewed with brotherly love”), wine, SEPTA, and, rather surprisingly, pickles. The first Steven Singer billboard appears on the right-hand side of the highway just before the Woodhaven Road exit, jutting up from a sparse patch of trees like a cowlick. It’s the classic I HATE STEVEN SINGER graphic, the same ad he unveiled one night in 2002 — then just a solitary billboard on 95 South right before the Center City exit — against the advice of literally everyone.

“The billboard company wouldn’t put it up,” Singer tells me one afternoon as we sit in his office, perched three floors directly above the corner of 8th and Walnut. “I had the idea for three years — the ad for the billboard, the script for the radio spot — and no one would run it. They said it would ruin my business and I’d go bankrupt.” He had to prepay and sign inch-thick contracts that would relieve any companies that ran his ads of liability should they cause his company to go under.

“But we’re in the love business,” his staff begged.

“But we have little kids,” his wife begged.

Singer was undeterred. “You guys aren’t seeing what I’m seeing,” he told them.

And so, one night after closing, Singer stealthily set his plan in motion. At midnight, his website switched over. “At first it looked really nice, classical music playing, and then suddenly it got all screwed up with graffiti. It looked like someone hacked it. We did it to our voicemail, too.” He hired a sign company to plaster his store with I HATE STEVEN SINGER signs in the middle of the night, so that when Jewelers’ Row stirred to life in the morning, it would discover with horror that Singer’s tidy corner store had been thoroughly and mercilessly graffitied.

That morning, Singer stood with Bob Hamburger, his longtime employee and one of a handful of people who knew the ad takeover was happening. Hamburger put his arm around his boss as they surveyed the store. “It’s not too late,” Hamburger said. “We can put the genie back in the bottle, and it will be over.”

“Bob,” Singer said, “it’s gonna be great. Don’t worry about it.”

It wasn’t the first bad idea Singer had ever had. In fact, the whole jewelry-selling thing was a terrible idea, if you were to believe the grizzled shop owner Singer met on Jewelers’ Row when he was a high-school senior.

“I remember the guy exactly,” says Singer. They’d met one day when Singer was doing his rounds for Norman Kivitz, a jewelry wholesaler on Sansom Street. Singer was working as a runner for Kivitz’s store, which meant he ping-ponged around the city on various errands, like picking up chains or clasps or watch batteries, dropping off diamonds to be cut and polished and set, running to the bank with half a million dollars in a bag. (“That’s just the way the business was back then.”)

The man at the shop Singer visited that day was nice enough, but he didn’t mince words. “Get out now,” he told Singer. “There are only two kinds of people in the jewelry business, the sharks and the jellyfish. You’re a jellyfish. You’re going to be eaten up.”

Ah.

“So that’s what this is all about?” I ask, gesturing behind him. Singer swivels in his chair, and it almost seems as though he’s forgotten about the massive five-foot-long shark there, mounted to the wall. Yes, he says, as if this is the most natural thing in the world. He explains that his friend (“one of the biggest diamond dealers in New York”) caught the shark a while back and displayed it in his office until he moved to a new glass-walled space on Fifth Avenue. Great views, but nowhere to hang the shark. So he gave it to Singer, the jellyfish jeweler. There’s a big (fake) shark head hanging next to it, and two small sharks on the bookcase.

Steven Singer (and his dog, Buddy) in his office

“It’s not that I like sharks so much, but I have it there to remind me of that moment, because my whole life, everybody told me I was going to be a loser,” says Singer. He remembers when a teacher at Northeast High School told him he was her biggest disappointment. “She goes, ‘You are one of the smartest, brightest students I’ve ever had, but you don’t apply yourself.’ I almost cried.” In his graduating class in 1975, it was a running joke that Singer was “most likely not to succeed,” alongside his friend Pete Ciarrocchi. Pete would go on to turn his parents’ Mayfair taproom into what everyone now knows as Chickie’s & Pete’s.

But Singer wasn’t lazy. He had dyslexia and ADHD, both undiagnosed. He’s since devised a series of work-arounds that he deploys when he’s speaking in public, which he does quite often. (He was the keynote speaker at Philadelphia University’s commencement in 2016, but it’s more likely you’ve heard him on the radio, yukking it up with Preston and Steve, Angelo Cataldi, Michael Smerconish, or Howard Stern.) But back in school, he would memorize words and pray that teachers would forget about him.

They couldn’t, of course, because he’s Steven Singer.

“He lights up a room,” says Matt Baker, who met Singer in fifth grade at Rhawnhurst Elementary. (Baker, who was in the “least likely to succeed” mix along with Singer and Ciarrocchi, is now the provost at Thomas Jefferson University — proof that Northeast High either gravely underestimated the class of 1975 or pissed its members off enough that they’ve succeeded out of spite.) “He was the funniest kid I’d ever met.”

Baker and Singer became fast friends, riding their bikes around the Rhawnhurst neighborhood where Singer lived with his family — mom, dad, two younger sisters, and a brother — in a modest twin rancher at Castor and Glendale avenues. He lived there until just after he graduated from high school, at which point he planned to go to Temple to study accounting. He never particularly wanted to be an accountant (does anyone, really?), but the aptitude test he’d taken singled it out as his ideal career. Plus, Singer’s father, who owned an air-conditioning and refrigeration company, had urged him to get a desk job. Singer had worked alongside his dad for years, the two of them up on blazing-hot rooftops in the height of summer, cramming in as many jobs as they could before business died down in the winter.

“My father said to me, ‘Listen, if you want to come work with me, that would be fine stuff. But in the meantime, you might as well go to college, learn something else, maybe try working at a place that has air-conditioning, where you wear a suit.’” Singer was working for Kivitz then, fitting in shifts throughout his senior year of high school. He didn’t love it at first, though he took to it eventually — a jellyfish swimming around in a world of diamonds and gold and glitz and beauty. He wasn’t making much money — only $68 a week, barely enough to afford the $2.25-a-day city parking. But he was hooked.

“I got addicted. I was full of piss and vinegar, and I was an idiot. But whatever I lacked in knowledge, I made up for in enthusiasm,” he says. So when Kivitz asked him to defer college for a semester to help out until Christmas, Singer agreed. He agreed again when Kivitz asked him to stay on after Christmas, and by the time the following September rolled around, Singer was all in. He’d taken a course at the Gemological Institute of America, which snuffed out any lingering plans of pursuing accounting. He was a jewelry man. For good.

Being a jewelry man and being a salesman are different things, though, and it wasn’t until Singer left Kivitz to be a traveling salesman for another wholesale company that he really sharpened his teeth. It was the tail end of the ’70s, the era of Saturday Night Fever, and Singer soon cracked the code of selling gold chains, persuading stuck-in-their-ways buyers — those who purchased the same few necklaces every time — to try out multiple lengths, thicknesses, and styles.

“I learned early on that the jewelry business is a business of idiots,” he explains. “So it wasn’t that I was so smart, but I was better than everybody else just by virtue of the fact that they were so dumb.”

Ruthless as it sounds, it was this appraisal of his competition that gave Singer — “a dopey 22-year-old kid who never took a business or accounting course in his life” — the brazen confidence to go out on his own and open a retail store on Jewelers’ Row, becoming the youngest first-generation jeweler in the oldest jewelry district in the country. Why not? But what Singer had in fortitude, he lacked in funds, so his first store was in an eight-by-18-foot converted stairwell — the smallest shop on Jewelers’ Row — with no heat, no running water or even a bathroom. He crammed in a few cases of jewelry, slapped his name on the window in a pretty script font, and on October 7, 1980, it was official.

Steven Singer Jewelers was open for business.

There are exactly 168 surveillance cameras in Steven Singer’s jewelry store. Some are obvious — futuristic gray orbs tucked in corners — and some are secret, like an outlet dangling off the wall that looks like it’s broken but is actually a motion detector. Singer doesn’t show me around the bright cases of jewelry in his showroom, but he does give me a tour of the server room on the third floor, which buzzes and hums with the millions of dollars’ worth of technology that keeps his merchandise safe.

It might all seem a tad excessive (considering the size of the building, the showroom itself is shockingly small, a narrow space of only 1,200 square feet), but there’s a lot of merchandise here. Singer runs his store like a wholesaler, which means there’s an entire vault — a literal 200-square-foot vault with six feet of reinforced steel and concrete underfoot and on all sides, and a door that weighs more than two tons and requires two people to unlock — packed with jewelry backstock. That way, if someone upstairs buys, say, the “miracle bracelet” — a diamond bauble designed so it looks bigger than it actually is (“like a Miracle Bra,” Singer says) — he can quickly replace it, and sell it again and again and again.

The vault is organized the way you’d imagine old-school Jewelers’ Row shops would organize their inventory — nothing fancy, just a bunch of plastic containers with small labeled drawers, shelves of binders filled with necklaces, and stacks of velvet-lined ring trays. Singer plops a huge, heavy plastic bag into my arms. It’s packed with a new bracelet he’s rolling out for Christmas. If all goes according to plan, it’ll be a bestseller. The design is a common style — silver X’s linked by diamonds, something you could find at Jared, Kay, or Zales. Plenty of his jewelry is like this — trendy designs tweaked to avoid copyright issues — but some pieces are more creative, dreamed up by Singer and half a dozen employees. He manufactures it across the world, from his own in-house workshop and another just up the street to sprawling facilities in New York, California, China, Italy, and India. And it all ends up here in this vault, ready to be shipped across the country. Because his iconic billboards aren’t just in our back yard. They’re in Indianapolis, Detroit, Los Angeles. They’re in Texas, which he says is a huge market for him. He once had a friend call him from Chicago.

“What the hell?” he said to Singer. “I just saw your billboard here. You’re everywhere I go. You’re like herpes.” Another friend of his — a celebrity you would know, but Singer doesn’t like to talk out of school — was at his vacation home in the Hamptons, sitting on the beach, trying to get away from it all, when a plane flew by with an I HATE STEVEN SINGER banner trailing behind it, a harsh streak of black and white against a blue sky.

“He calls me and goes, ‘Motherfucker. I can’t get rid of you.’” Singer laughs. His plan is working. Everyone hates him.

It took some time to get here. He started out in 1980 with a few TV ads and then moved to radio and print: “It was horrendous. Everything sucked and nothing worked, because I was doing bad versions of everybody else’s ads.” He soon figured out the best path forward: “If everyone goes left, we go right.”

Enter Howard Stern.

Singer had listened to Stern’s show as he drove to and from New York, and he took to the host’s audacious personality and off-color brand. “I said to myself, man, if he ever comes to town, I need to get him,” Singer says. Then, in 1986, it was announced that Stern was testing the Philly market for his first syndication, and he had his chance.

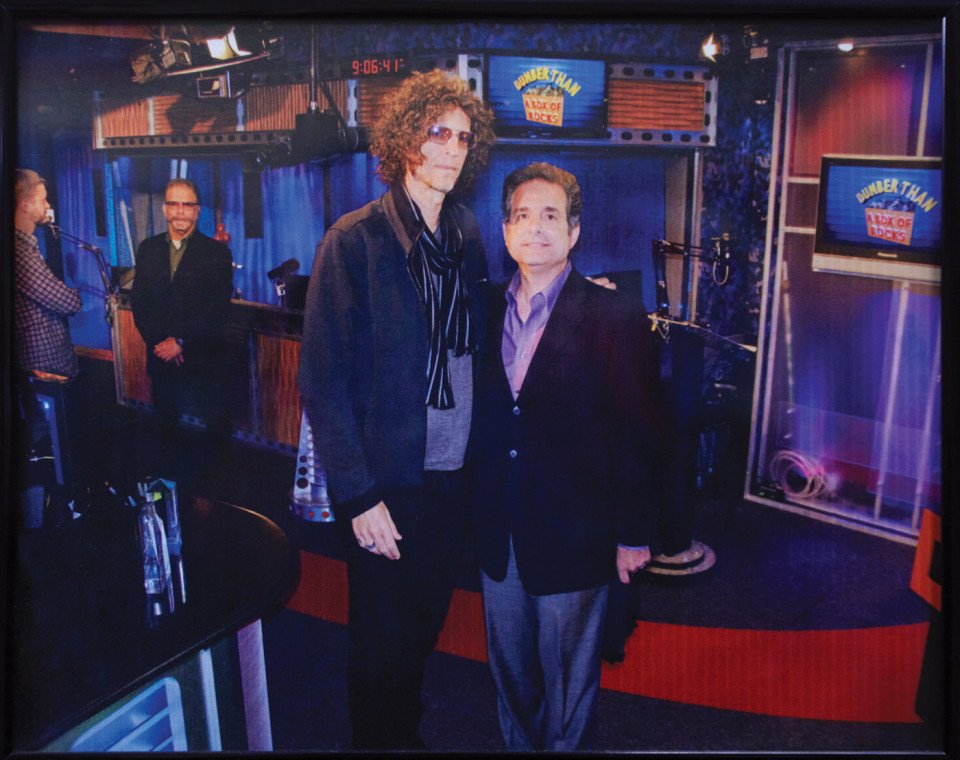

Steven Singer with Howard Stern in 2015

Alas, the jewelry industry is full of sharks circling and waiting for something to drop, so while Singer was busy remortgaging his house to pay for the $700 advertising spot, Barsky Diamonds, a Jewelers’ Row stalwart since 1898, was the first to bite. But soon there was a problem.

“My father was a very religious guy. He went to synagogue every day, was on the board at his temple,” says that store’s current owner, Jeff Barsky. “We had a lot of people of faith complain to him about Howard Stern.” They threatened to tell their fellow congregants not to shop at Barsky if he continued to advertise with the shock jock. So Barsky pulled out, and Singer was in.

Everybody else was going left. Steven Singer had officially veered off to the right.

“Let me tell you something great about Steven Singer,” Howard Stern said to his listeners one morning in the brambly thick of the Me Too movement. “Unlike Harvey Weinstein, he won’t rape you. Steven’s in his store every day, and if you walk in, he may give you a reach-around, a little finger, but over the clothes only.”

“He said that?” I ask Singer. We’re still in his office; the streetlights outside have flickered on. Earlier today, Singer was flummoxed that I was writing this piece. All of his stories are boring and terrible, he told me, nothing worth writing about. But hours later, we’re still here, and he’s still talking, and I’m still riveted. They’re selling diamond rings downstairs, pieces to be presented at picture-perfect engagements and exchanged solemnly on sacred altars, and we’re up here talking about dicks.

“I always said to Howard, ‘I don’t care what you say about me,’” Singer tells me. “‘Just mention my name once in a while.’” It’s a brilliant move, like when he offered up his store as a gifting closet for Stern’s show. Instead of doling out prizes like crappy tissue-box covers and $10 Applebee’s coupons for on-air contests, Stern could offer callers $500 gift certificates to Steven Singer Jewelers, or diamond stud earrings, or silver bracelets. Singer was still only advertising in the Philly market, but now he was being talked about in the context of the show, which by that time was syndicated across the country.

People all over the country don’t know where 138½ South 8th Street in Philadelphia is, though, and neither did Stern. That was Singer’s new location, the one he’d moved to in 1984 — a “piece-of-shit store” next to Robbins Diamonds, known locally as “Robbins 8th and Walnut.” Robbins had been a Jewelers’ Row institution for decades, so much so that Singer used it as a beacon to direct shoppers to his place — “one store in from 8th and Walnut.” In fact, he still refers to his current location, a three-story-plus-basement building he bought in 1999, in the context of Robbins: Singer is the jeweler on the other corner of 8th and Walnut.

He doesn’t need to do this anymore, of course. Robbins Diamonds is now the chain bakery Le Pain Quotidien.

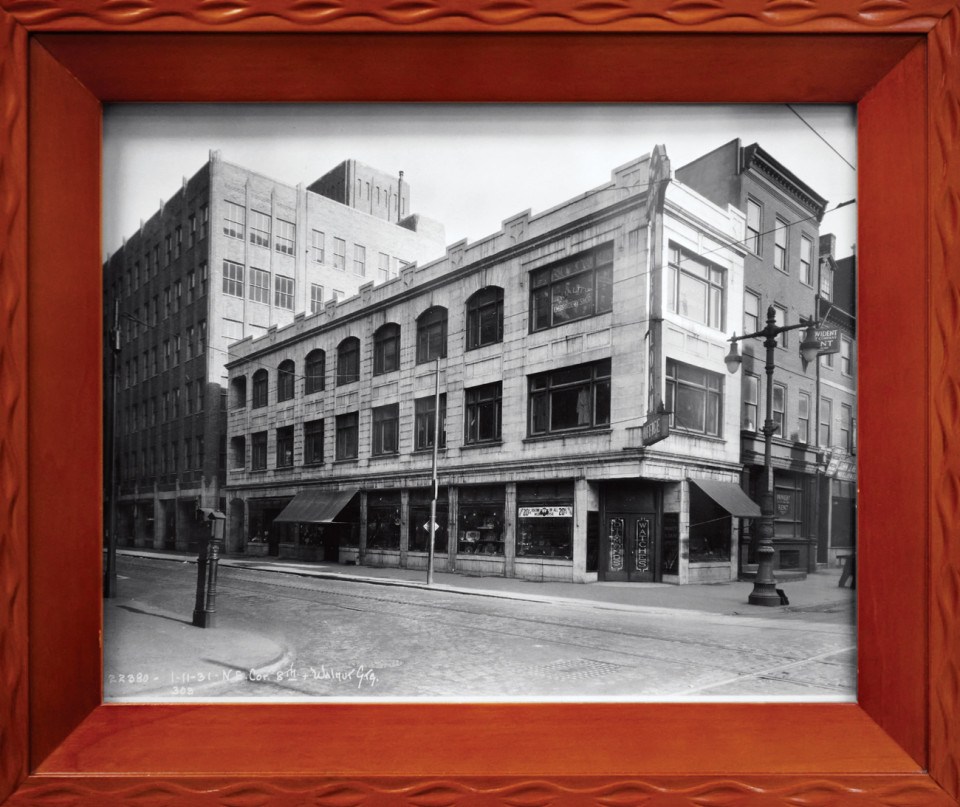

The exterior of Steven Singer’s building in 1931

“I think he’s always operated under the fear of becoming irrelevant,” says LeeAnn Kindness, his former marketing director. “So he’s always been someone who has a big, scary, audacious goal pinned to the wall and is like, ‘How are we going to get there?’” (Jac Griffin, his current chief of staff, who has worked for him for almost 18 years, agrees: “There have been times where he’s like, ‘What if we got an elephant to walk down the street?’ I don’t know how to do that. I don’t know how to source an elephant.”)

He’s had lots of ideas, some of which were inspired by seeing something else and wanting to replicate it, but with his trademark Singer spin. (“I don’t invent the wheel. I just improve it,” he says.) Part of Singer’s brilliance is his keen knack for identifying worthy coattails and holding on for the ride. He did it with Stern, sensing his ball-of-fire potential and “riding it all the way up.” He did it with the viral Miller Lite commercial that ran in 2003. You might remember it — the one with the hot girls in their underwear wrestling in a fountain and then in liquid concrete, arguing over whether the beer “tastes great” or is “less filling.” Lots of people saw the ad as smut. Singer saw it as an opportunity. He tasked Kindness with figuring out how to do mud-wrestling in the store. Maybe they could fill the place up with whipped cream? Jell-O? Kindness found a better idea: a bubble machine.

Bingo. Singer would host the “World’s Largest Bubble Bath.” They blanketed the store in tarps; got the bubble machines running at 4 a.m.; set up a broadcasting space for Angelo Cataldi, who was then the top dog of sports radio at WIP; and invited a troop of, yes, hot girls in bikinis and goggles to dive through the bubbles to find plastic Easter eggs stuffed with prizes, the top two being a $10,000 diamond bracelet and keys to a slick Harley-Davidson motorcycle parked out front. (Singer tried to block off all of 8th Street and make it a huge outdoor bubble bath, but the city vetoed the stunt — something about bus routes and, you know, basic public safety.) The event was objectively dumb, schlocky, lowbrow. It was also a huge success. It ran for a decade. By the end, around 40 couples had gotten engaged in the bubble bath; a few dozen even got married there. Cataldi became an ordained minister on the internet.

Singer worked with Cataldi again, for two decades sponsoring WIP’s annual Wing Bowl, an equally lowbrow event at which competitive eaters vied to consume the most chicken wings. Singer presented each winner with a gold-and-diamond championship ring as big and gaudy as a Super Bowl ring, plus cash. He’s done other stunt marketing too; in 2023, he made a show of handing out $3 million worth of lab-grown diamonds for free to a long line of people outside his store, “just to prove how worthless fake diamonds are.” Most recently, he very publicly offered to give Travis Kelce a free engagement ring for Taylor Swift, once again carving a foothold in the cultural zeitgeist. (Page Six picked up the story, creating an even bigger splash.) He’s already made the ring — a seven-and-a-half-carat emerald-cut diamond set in platinum. He asks an employee to bring it up from the vault, makes me try it on. It’s … big.

I try to find a delicate way to ask my next question so I don’t offend him: “Do you ever worry that all of this, um, dilutes your brand?” (In other words: Do people really want to buy diamond jewelry from a guy who uses “Does size matter?” as his tagline?)

“We don’t sell to people with a stick up their ass. We like to have fun. If somebody doesn’t have a sense of humor, they’re not our customer,” Singer says. He once declared that if Tiffany and Walmart got together and had a baby, it would be Steven Singer Jewelers — middle of the road, bread-and-butter. “I always say that we do nice well.”

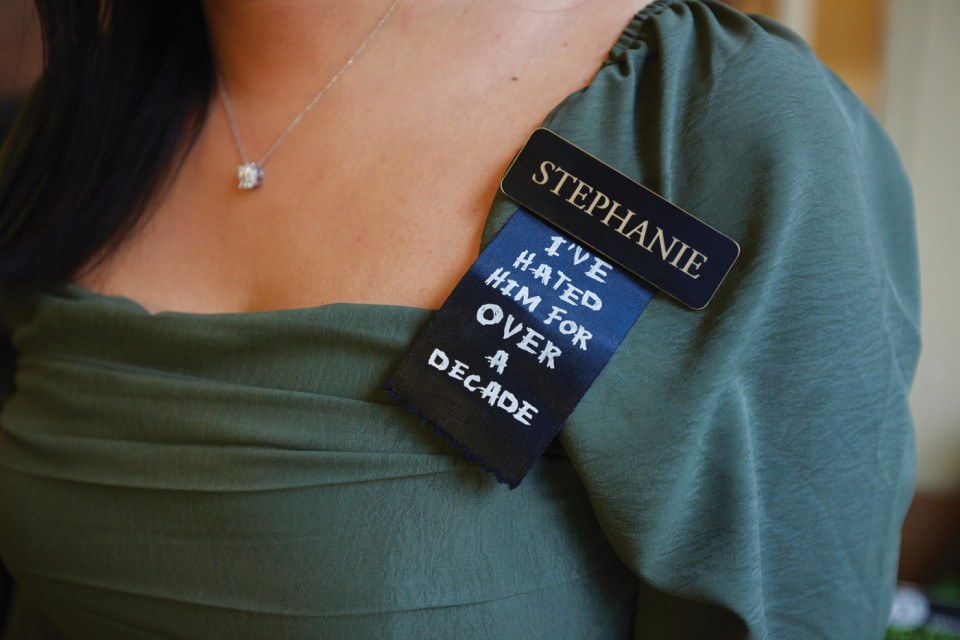

An employee ID badge

For all his public bravado, Singer is actually quite introspective. He acutely understands his brand and where he fits in the industry — an independent retailer who’s managed to snag a piece of the mid-level pie, putting himself in the conversation alongside brands like Jared and Kay. (He’s actually been sent a few cease-and-desist orders by their parent company, Signet, over his use of their names in his ads.) He knows exactly who his customers are, and he’s always known who he is, even as everything he knew was shaken. Because he shouldn’t be here right now, talking to me in his store.

He should be dead.

He learned this in 2019, when doctors discovered that all of his arteries were nearly fully blocked. Stents and open-heart surgery didn’t work; the arteries simply filled up again. Over the next two and a half years, Singer would have 13 heart operations. Doctors gave him six months to live. He didn’t tell his two grown children the news right away, nor did he tell his wife, Adrienne, whom he’s known since high school and been with nearly as long. Instead, he went to the Women’s SPCA to get a dog for her, so she wouldn’t be alone when he died.

Singer seems to become smaller, older, softer, as he talks about it. He tears up when he discusses his health problems, but he cries, hard, when he talks about his dog, Buddy, who, Singer would discover, also has heart problems.

“I swear he saved my life,” says Singer. Buddy is a fixture at the office and even has his own business card: “half poodle/half human.” There’s a painting of Buddy on the wall; it hangs beneath the honorary doctorate Singer got from Philadelphia University in 2016. To the right of the painting are two framed awards Singer won for his advertising; they also mention Dennis Steele, the guy who inspired the “I hate Steven Singer” tagline in the first place. (The real story is this: Steele bought a diamond ring for a 20th wedding anniversary gift to his wife. She thanked him in, er, X-rated fashion, and nine months later, the couple — already parents to two adult children — came to the store with their newborn. Steele blamed Singer for landing them back in the world of sleepless nights and dirty diapers, told him he hated him — and the rest is Philly advertising history.)

There’s only so much wall space in Singer’s office — the shark takes up a fair amount of real estate — so his collection of framed personal memorabilia spreads out into the hallway and down the stairwell, like a museum exhibit of his life. There are more awards here, old press clippings, ticket stubs from World Series games and Super Bowls. There are old photos of Singer — he was heavier then, and had darker, thicker hair — with a slew of celebrities, like Aerosmith’s Steven Tyler, Howard Stern (whom he now considers a personal friend), and John Mayer.

But there are also pictures of him with less recognizable people, like Ellen Saracini, the widow of Victor Saracini, who was the pilot of the second plane flown into the World Trade Center. Talk-radio host and author Michael Smerconish is there with the pair, and he and Saracini are wearing small 9/11 remembrance pins designed and manufactured by Singer. He partnered with Smerconish to sell the pins for $10 each, and they donated all the profits to 9/11 charities. In 12 years, they raised more than a million dollars, which helped fund the 9/11 memorials in Yardley and Shanksville. There’s a plaque and a letter from the White House recognizing the jeweler for his commitment to the Flight 93 National Memorial campaign. Singer attended the memorial’s dedication in 2011, prepared as always with a bag of merchandise in case somebody needed an extra pin. He remembers Bill Clinton shuffling around in the chaos backstage. “You think it’s all carefully orchestrated,” he confides, “but they’re all just winging it.”

Singer said something similar to LeeAnn Kindness once. “I’m going to say it exactly the way he said it,” she tells me: “‘Nobody knows what the fuck they’re doing. So just go through life, do your best, and figure it out.’”

Singer is still figuring it out. Jewelers’ Row isn’t the same as it used to be. In its glitzy heyday, there were 351 jewelry shops there. Now there are only about 110, and the quality of the stores has plummeted.

“It’s on a permanent decline,” Singer says of the district. “I don’t think it’s going to be in its present form in the next five or 10 years.” So it’s time to evolve again. But Steven Singer is a master of evolution. He embraced e-commerce quickly, entrusting Kindness to build out his first website, which sold exactly one item: those now-iconic gold-dipped roses, in two different colors. He eagerly harnessed social media, too, hiring a team of people to take the reins and run with them.

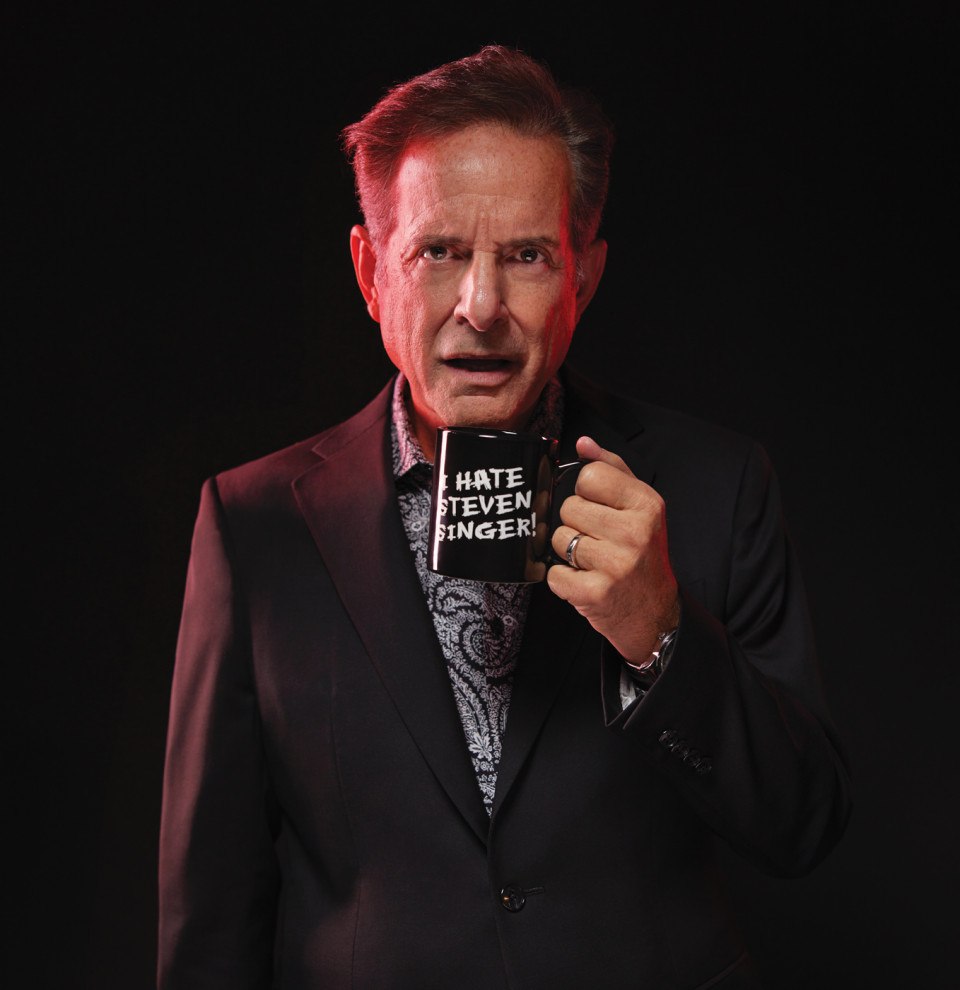

Steven Singer

“He recognizes things in people that you might not recognize in yourself,” Kindness, who now works in product innovation at Wawa, tells me. It’s part of the reason so many of his staffers stick around; employees wear name tags that reveal how long they’ve worked for Singer, in a characteristically irreverent way: I’ve hated him for over three years. I’ve hated him for over a decade. Bob Hamburger’s name tag reads: I’ve hated him for over 40 years.

Perhaps it’s these employees who will shepherd Steven Singer’s brand forward in the future. He’s in good health now, thanks in part to a modified vegan diet and daily exercise. (Buddy has also had a miraculous turnaround.) But his store celebrated its 44th anniversary this past October; next month will mark Singer’s 50th year in the jewelry business. Steven Singer might not be dying anytime soon, but he won’t work forever. His kids don’t want to take over the business; his daughter works at Princeton University, and his son is in real estate. And so he’s set the stage for his staff, kept on heading right when everyone else went left.

“His advertising is so much a part of the fabric of the city and the surrounding area,” says Smerconish. “There are just a handful of true Philly characters, and Steven’s one of them, and he’s earned his spot.”

Singer is working on a business-continuation plan now. He has big ideas still, starting with opening a second location in Newtown later this year. After that, he wants to open 10 more area stores; then, if all goes well, he’ll go national. He worries, deeply, about his employees and seems to be making sure the foundation he’s building for them is big and strong enough to last, just as he did with his vault downstairs.

And yet I look at the shark above his head, and the lifetime of memorabilia that surrounds him, and I wonder what will happen when the man everyone hates goes away. Steven Singer has swept thousands of people into his sparkly ecosystem with his singular brand of bawdy humor, gimmicks, and gusto, all so entwined with who he is that it seems impossible it should all survive without him. He’s a grand illusionist, spinning his empire out of the dim, closed-in world of Jewelers’ Row.

Maybe, I think, Matt Baker, Singer’s best friend since childhood, put it best: “He’s the magic, and he always was.”

Published as “I (Don’t) Hate Steven Singer” in the February 2025 issue of Philadelphia magazine.