How One Philadelphia Prison Could Change Incarceration in America

A ground-breaking partnership between Drexel and the Pennsylvania Department of Corrections is revolutionizing the U.S. prison system, one block at a time.

Kevin “Amir” Bowman and C.O. Turquoise Danford share a meal at SCI prison in Chester. / Photograph by Swedish Television SVT/John Stark

Inside the imposing beige walls of the state correctional institution in Chester, there is a fish tank whose inhabitants are part of something bigger than themselves. There are nearly two dozen of them — African cichlids, tetras, and a lone angelfish — swimming among artificial coral and rock formations. Tiny bubbles rise from the helmet of a plastic scuba diver through the crystal-clear water.

Kevin “Amir” Bowman used to pull up a seat in front of the fish and gaze, watching them dart back and forth inside the tank or lazily drift on by. That was before he got out, exonerated last March after serving 34 years of a life sentence he thought would take him to his death. He’d bounced around through eight prisons in that time, moved from one to the next by the powers that be, always alert to the sound of distress and the threat of violence, no matter which unit he was placed in.

In Chester’s Little Scandinavia, though, he found something different — a unit modeled on principles adopted from Norway and Sweden, where even those countries’ worst offenders are treated with humanity and given rights and privileges unheard of in American prisons. There, he was given his own cell, shared a kitchen with the other 63 men on the unit, and could be called by his chosen name, Amir, not just his last name or his prisoner identification number, BF6556.

He wasn’t alone in watching the fish. The unit’s other members did it too. And maybe they each saw something different, but he knows what he found in their company.

Inside Little Scandinavia / Photograph by Rachel Wisniewski

“Peace and tranquility,” says Bowman, 59. “You’re looking at a whole other life in its environment, living.”

The fish tank sits just inside the entrance to Little Scandinavia, serving as a beacon of sorts for the change happening here. The unit opened in March 2020 as part of a novel research project jointly led by Jordan M. Hyatt, an associate professor of sociology and justice studies at Drexel University, and Synøve N. Andersen, an associate professor of criminology at the University of Oslo, who are studying the impact of Scandinavian-style reforms on both inmates and officers.

To create Little Scandinavia, the Department of Corrections renovated Charlie Alpha, a first-floor block that had once held 128 men in 64 cells, like all the rest at Chester. Today, it doesn’t resemble a prison very much at all.

Modular furniture gives inmates a gathering space for conversation and community meetings. A treadmill and elliptical machine offer them a chance to exercise anytime they want. Noise dampeners on the ceiling keep the common area quiet enough that during a visit this summer the only obtrusive sound came from an active air conditioner. In the kitchen, residents cook food they’ve ordered with their own money from a local grocery store on a set of electric stoves still sparkling four years after they were installed. There are duplicates of everything so the unit’s Muslim members can keep halal. Everyone respects boundaries, and everyone maintains order.

The furniture in the unit differs from that in other units in Chester, encouraging interaction / Photograph by Swedish Television SVT/John Stark

“It’s spotless,” Andersen says. “My kitchen does not look anything like that.”

If the superficial changes make it immediately clear that something different is happening here, the less visible aspects of the overhaul reveal the depth of the reforms — and their potential to change the lives of those who enter the unit and set eyes on that fish tank.

The inmate-versus-officer dynamic has dissolved, replaced by a sense that everyone is working toward the same goal. Staff have been retrained and renamed — contact staff, rather than correctional officers — in an effort to support residents as they prepare for life after prison. There are three staff on the unit at a time, compared with one on a standard block with twice as many men. The officers and inmates cook and exercise and play games together. They share meals. They share something of themselves, liberated from policies that normally forbid fraternization and keep everyone on one side or the other of a clear divide.

This is still a prison, and there is no mistaking that the men are still incarcerated, but they speak of Little Scandinavia with fondness and an appreciation for their newfound independence. After years sharing cells in crowded, cacophonous blocks, they describe relief from the constant pressure and gratitude for being given the space for self-reflection. There is a sense of community in Little Scandinavia that belies the building in which it’s housed.

“Everything you were missing in an upbringing — mentorship, guidance, a peaceful existence — you can have here,” says Eliezer, 51, who has served 29 years of a life sentence. (The DOC requested that inmates’ last names not be published.)

American prisons don’t work. They’re overfilled, unsafe, and expensive. The country spends at least $80 billion a year on its federal and state institutions and gets little in return. The majority of those who are released end up going back, and the unemployment rate for the formerly incarcerated is at least six times the national rate. If the goal of corrections is to rehabilitate offenders, the conditions inside America’s prisons are an inherent obstacle. Little Scandinavia suggests that a healthier environment is possible — and that it would make a genuine difference in the lives of the incarcerated.

Hyatt and Andersen’s work is still ongoing. Data on prisoner and officer well-being won’t be available until next year, and the block’s recidivism rate will take longer to identify. But Little Scandinavia’s lack of violence and the perspectives of its residents and staff suggest that the experiment is already answering some of the grander questions posed by the project: Can American prisons be run differently? How will inmates respond to opportunity? What would happen if humanity and dignity were instilled in institutions that have for so long robbed people of both?

Welcome to Scandinavia

Little Scandinavia is the concretization of ideas Hyatt and Andersen have been discussing since they met at an academic conference in 2015 and began collaborating. In the years that followed, they began organizing exchange programs for Drexel students that include visits to Norwegian and Swedish prisons, renowned for being the most humane and effective in the world.

In Pennsylvania, the recidivism rate after three years is 65 percent, in line with U.S. averages that reach closer to 80 percent after five years. In Norway, the rate is around 20 percent after two years and 25 percent after five years, according to Are Høidal, the former governor of Halden Prison, who is now a senior adviser for Norway’s correctional service and a member of the research project’s advisory board.

Høidal came to Chester in 2017 on a visit organized by Hyatt, planting the first seeds for the change that soon took root. “From Norway, Pennsylvania’s prisons appear cruel and unusual,” the Inquirer’s headline read. The next year, at a meeting at DOC headquarters, Hyatt and Andersen presented to then-Secretary John Wetzel the idea of extending their research on Scandinavian prisons to Pennsylvania. The DOC chose a stand-alone unit as its preferred approach.

Residents and staff cook a meal together / Photograph by Swedish Television SVT/John Stark

“Every single person who goes to a prison in Scandinavia comes back and says, ‘We should do something like this here,’” says Hyatt. But until Pennsylvania tried its hand, nobody had. There was no model for the DOC’s undertaking, he emphasizes — “no prior evidence, no safety net, nothing to compare to.”

The DOC gave the green light for a delegation of department officials and employees to tour Scandinavian prisons in 2019 and spent $310,000 in startup costs to restructure the unit, Secretary Laurel Harry said earlier this year. Arnold Ventures, a Houston-based philanthropy focused on addressing the root causes of institutional injustice, was the primary funder of the delegation’s visit and two more, in 2022 and 2024, through a grant supporting Hyatt and Andersen’s research.

When staff from Chester visited Norway in 2019, touring Halden and other prisons and then working inside them for two weeks, they were stunned by what they saw: officers and inmates eating meals together, playing video games, laughing.

“I was blown away. It was jarring, eye-opening,” says Paige Devane, one of the unit’s contact officers, who began working at Chester in 2018. “I said, ‘Oh my God, I’ve been trained wrong.’”

Beyond the unusual approach to architecture and design, which the DOC would later import to Little Scandinavia, Devane noticed more subtle indications that Norway’s revolutionary methods were working. Officers’ shoulders weren’t tense. Their hands weren’t clenched. They didn’t seem to live in fear of the next fight. When she and her fellow staff returned, “everyone was on fire.” They were ready for change.

You don’t realize how un-normal you’ve been living. Once you’re here the contrast is so obvious.” — Richie, a resident of Little Scandinavia

The unit was fixed up — new furniture, a softer paint palette, plants to breathe life into the room — and the first six men, all lifers, moved in. Little Scandinavia was designed to reflect the broader population at Chester, where roughly 10 percent of inmates serve life sentences. Residents are selected via lottery, not based on good behavior.

Amir Bowman was shocked to be selected. “I don’t get blessings like that,” he says. His cell was “immaculate,” complete with a small refrigerator, a television on the wall, and a new mattress. Most important was the absence of a cellmate.

“It was bizarre,” he says, “but it was beautiful.”

The unit’s first residents became known as the Original 6. Their input shaped how the block is run — community meetings when new residents move in, for example — and they took on mentorship roles, offering what wisdom and support they could to the younger inmates who later joined them. Because of the pandemic, the unit didn’t fill out until May 2022.

At the beginning, it took time for the men to adjust to a living situation that felt strangely normal for the first time in years. For the first week, it was so quiet they could hardly sleep.

“You get used to years of the noise,” says Eliezer, who painted the murals in the unit’s entrance — a hiker atop Norwegian fjords and a globe with Scandinavia and Pennsylvania highlighted beneath the words “Humanity Across the World.” “Suddenly you could hear a pin drop. You could hear yourself think.”

A mural painted by one of the residents / Photograph by Rachel Wisniewski

Prison is defined by “chaos and overstimulation,” says Richie, one of the six original lifers. The 60-year-old South Philadelphian’s thinning gray hair and rectangular wire-rim glasses suggest the weariness of a man who’s been in prison for 37 years. When he began interviewing his fellow inmates for a newsletter and for a documentary produced by Sweden’s public broadcasting network, he kept hearing the same refrain: “I have so much less stress, so much less anxiety.”

“You don’t realize how un-normal you’ve been living,” Richie says. “Once you’re here the contrast is so obvious.”

Amon, 27, broad-shouldered with braids and thick-rimmed glasses, has spent a comparatively brief three and a half years inside. Living in the relative calm of Little Scandinavia allowed him to realize he’d been depressed for two years in traditional housing units. “It was a hostile environment. Heinous,” he says. “It makes you feel degraded.”

Moving into Little Scandinavia felt like “a transition from not having to having” for Justin, who came to the unit last November as he neared the expected end of a 15-year stint. “We take care of each other,” he says. “There’s a sense of family.”

The fish play some small part in that, and so do the dogs and cats residents are allowed to keep, rescued from euthanasia at local shelters. (The pets are part of a broader program throughout the prison.) A grin washes over Justin’s face when he mentions Boogs, his tuxedo cat. When Boogs injured himself earlier this year jumping down from the unit’s second tier and had to be taken to the vet, Justin burrowed into his cell for hours waiting for his return. The animals offer comfort, but they mean something more than that too.

“It makes you feel human,” Justin says, “like you can be loved by someone other than yourself.”

Life in Little Scandinavia is suffused with these opportunities to feel whole again — the freedom to cook a meal that tastes like home; easy access to a phone to call an ailing mother or a child on their birthday; the chance to sit alone in a room, music playing, processing life in here and the future out there.

“When we first came here, I can’t tell you how many men said, ‘I was able to cry for the first time in years,’” Devane says. “We have a lot of unhealed trauma.”

From what she sees, Andersen says, American prisons emphasize retribution. Wrongdoing is met with punishment. Pain begets pain. Trauma persists. In Sweden and Norway, prison is more about what comes after. Sentences are shorter — a maximum of 21 years in Norway, or 30 years for terrorism — and spent learning skills that can be used on the outside. Inmates retain their rights, including the right to vote, which they’re encouraged to do. They’re asked to change and given a setting and support system that make it possible.

The difference from the U.S. model is stark, and it prompts a question that seems to be on the minds of everyone who steps foot in Little Scandinavia: What’s the purpose, Andersen asks, of punishment, broadly speaking, and prison more specifically?

A History Lesson

SCI Chester / Photograph by Swedish Television SVT/John Stark

From a historical perspective, the Philadelphia area seems an appropriate place to make such inquiries. It was on farmland then just outside the city that Benjamin Rush and the Philadelphia Society for Alleviating the Miseries of Public Prisons persuaded the state to build Eastern State Penitentiary, an experiment in prison reform that reverberated around the world.

When Eastern State opened in 1829, Philadelphia’s prisons were little more than pens in which to corral criminals and those accused. They were rife with violence, abuse, and disease. Rush and his fellow reformers believed they could establish something better — less punishing and more effective at creating change. What they built was revolutionary in its own way, if ultimately not exactly humane.

Inside the intimidating medieval facade that surrounded Eastern State, seven long wings radiated from a central rotunda. The 250 prisoners were given their own cells and hooded upon entry and exit to avoid interaction with fellow inmates or guards. Food was passed through small openings in cell doors to avoid contact. Prisoners were kept in complete isolation, given little more than a Bible and a skylight over their heads — the word and the eye of God overseeing their penitence.

After his visit in 1831, the French aristocrat Alexis de Tocqueville wrote to his government with admiration for what he saw. “Can there be a combination more powerful for reformation than that of a prison which hands over the prisoner to all the trials of solitude, leads him through reflection to remorse, through religion to hope?”

The building’s design and the principles of its operation were intended to inspire regret and rehabilitation. As we know from modern research on the physical and mental toll taken by solitary confinement, it surely did little of the latter. Nonetheless, Eastern State, which rejected the then-common use of corporal punishment, became a model for the progressive treatment of inmates. It established penitence as the institution’s purpose and isolation as its tool in that aim — punishment of another sort. More than 300 prisons around the world were developed with Eastern State as the model, and its methods became known as the Pennsylvania system. It was closed in 1971 and today is a museum.

To those involved, Little Scandinavia represents a chance to begin turning the page on the long history of inhumane treatment in American prisons. There, solitude gives way to community. It’s a way to consider all that we take for granted on the outside that those on the inside have had taken away: the autonomy to decide when and what to eat, to turn on a light to read during a sleepless night, to retreat from tension or ask for help when it’s needed.

“It presents an opportunity to think about what pieces of that deprivation are intentional parts of the punishment — what we intend as a society — and what is a function of history and pragmatic decisions like budgetary constraints. And it forces us to think about where we as a society want to be with regard to punishing people after they’ve committed crimes and then welcoming them back into the community,” Hyatt says. “People can disagree about those things, but this project encapsulates and touches on all those issues in a very concrete way. We hope it encourages some amount of reflection.”

For State Representative Jordan Harris, D-Philadelphia, who has visited roughly half of the state’s prisons as part of his efforts toward criminal justice reform, Little Scandinavia demonstrates that it’s possible to be “firm on crime and fair on humanity at the same time.” During a recent visit to Chester, he was struck by the sense of dignity throughout the unit — a reminder that prison doesn’t have to force the incarcerated to suffer and that suffering doesn’t lead to reformation.

“Incarceration itself is the punishment,” says Harris, chair of the state House Appropriations Committee. “The fact that you can’t go home is the punishment. The fact that you can’t see your family is the punishment.”

Amir Bowman spent 34 years living with that punishment and plenty more on top of it. He saw the way the indignities can fester — inhumane treatment from officers, the threat of violence that never lifts, the physical toll of violence itself. Contemporary departments of corrections often refer to the three C’s: care, custody, and control. But he didn’t see much of the first one until he reached Little Scandinavia.

Residents and staff order dinner ingredients online / Photograph by Swedish Television SVT/John Stark

“You take out care and it’s just custody and control. ‘I have you and I’m going to control you.’ That’s where you breed an angry man or woman,” he says.

That’s borne out in America’s alarming recidivism rates, among the highest in the world, which speak to the prison system’s failures during incarceration and broader societal failures to support reintegration afterward. Nearly two million Americans are incarcerated in state or federal prisons or local jails at any given time, and nearly six million, roughly two percent of the entire population, are under supervision by the criminal legal system, including probation and parole. Prison overcrowding makes practices like those on display in Little Scandinavia a costly proposition, given that it houses half as many men as a typical unit. Pennsylvania already spends about $64,000 annually per inmate, according to the DOC, only to see the majority of those who go home eventually return.

The overcrowding, lack of care, and recidivism are all connected, Bowman says. Roughly one-quarter of inmates experience physical assault during their stays, research has found, while post-traumatic stress disorder is estimated to affect 18 percent of male and 40 percent of female inmates.

“Take a person from Little Scandinavia and take a person from a tense environment in prison: Which one would you rather have living next to you?” Bowman asks.

Given the dangerous, ineffective, and costly nature of American prisons, Little Scandinavia offers a road map toward something better, Harris says.

“We have to reimagine justice in our commonwealth and, quite honestly, in America,” he says. “What we’re doing isn’t working, and there are so many across the world who are doing it better.”

The Nordic Model

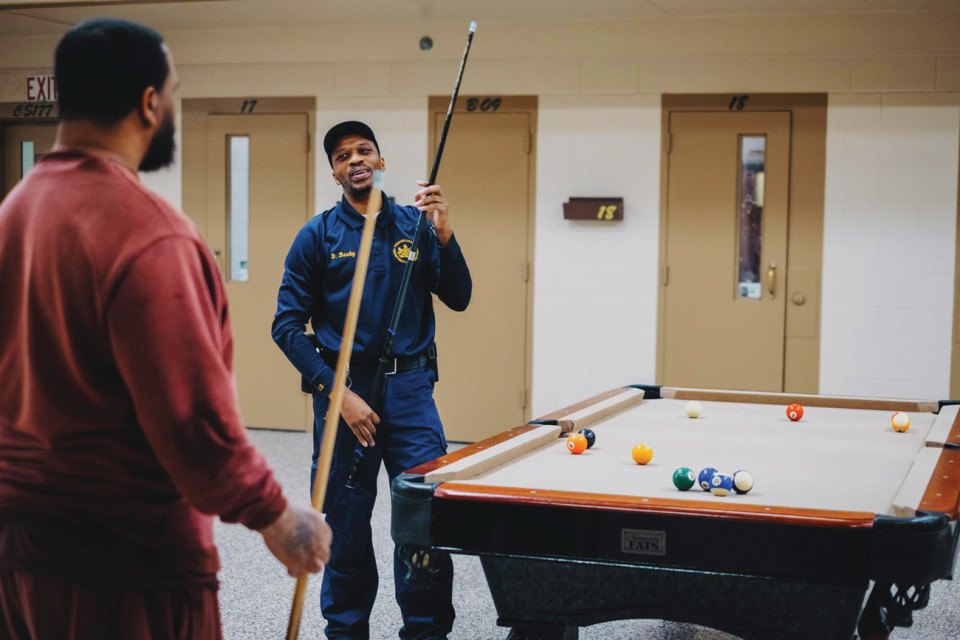

Contact officer David Baxley plays pool with a Little Scandinavia resident / Photograph by Swedish Television SVT/John Stark

Norway’s prison system wasn’t always a role model.

When Are Høidal entered the correctional service in the 1980s, prison facilities were outdated and so was penal philosophy. Oslo Prison, which he joined in 1989 and later ran for a decade, had been in operation since 1851 and was designed with Eastern State in mind.

Recidivism rates across the country were high, pushing past 65 percent. Escapes were common, drug abuse and violence were prevalent, riots broke out from time to time, and two officers were killed by inmates in the span of a few years. “It looked,” he says, “like the United States.”

To lift itself out of this morass, the service delivered a parliamentary report in 1997 that defined new values, principles, objectives, and performance goals. (Another report followed in 2008.) It may sound like a stuffy bit of bureaucracy, but Høidal says it turned everything around. The report aimed to both reduce recidivism and address the stigma and unintended consequences of serving time that hinder reintegration. Importantly, it had the support of every political party in Norway, as well as of the officers’ union.

The report focused its attention on the role of the officers themselves. Before it was published, they were merely guards, focused on security work. They didn’t converse, “especially not about their problems,” Høidal says. The report recommended that officers serve as something more like social workers, emphasizing their role in the rehabilitation of the incarcerated population. The subjects studied during officers’ two years of education and training changed too. Now they would learn about ethics, human rights, and the law.

Central to the new approach was the concept of dynamic security, a transition from static methods that had traditionally defined prisons — cuffs and bars and doors that limit movement and enforce control. Officers instead spent their days with inmates, building a rapport that accomplished more than restricting liberties ever could. Violence decreased significantly, particularly against staff, who were no longer seen as the enemy, Høidal says. Dynamic security is one of two defining principles Little Scandinavia adopted from its namesake.

“We’re disarming people by getting to know them,” says Devane, one of the Chester unit’s original officers.

Beyond the philosophical shift in officers’ responsibilities, the other principle that has guided Norway’s correctional service since the report is normality. Life inside should reflect life outside, as much as possible. Rights are retained. Health care is preserved. At Halden Prison, the first built after the report, which Høidal ran from its opening in 2009 until 2022, architecture was considered a rehabilitative tool. Thus, housing units replaced cold, harsh materials with comfortable furniture, softened edges, and amenities. Normality is the second leg upon which Little Scandinavia stands.

It took five years to implement the new way of working in Oslo, Høidal says, and longer to shift the system as a whole. But in time, recidivism rates plummeted. Norway’s incarcerated population, once around 5,000, is now less than 3,000. The difference in size is an important distinction in considering the importation of Norwegian principles to the United States. SCI Chester holds more than 1,000 men, and around 40,000 people are incarcerated throughout Pennsylvania.

Little Scandinavia / Photograph by Swedish Television SVT/John Stark

“Change is possible, but it takes time,” says Andersen, the Norwegian researcher. “It’s not done in a heartbeat. People have to stay invested and committed for a long time to see actual, system-level change.”

In Sweden, too, penal philosophies evolved in the second half of the 20th century, says Martin Gillå, head of the office of international affairs for the Swedish prison and probation service and a member of Hyatt and Andersen’s advisory board. The system developed around a recognition that socioeconomic factors contribute significantly to many criminal offenses — or, as he says, that “the perpetrator is a victim of circumstances.” Offenses are considered to be a trespass against the state, a violation of the social contract rather than a crime against a victim.

In the U.S., by contrast, the involvement of victims and their relatives in the sentencing process suggests a greater concern with retribution and redress, Gillå says. He notes the April execution of Brian Dorsey in Missouri despite pleas for clemency from 72 corrections officials, among others, who described him as a changed man. “Justice needs to be served,” he says with a hint of sarcasm. “You can ask yourself, what kind of justice?”

The Swedish prison service’s motto translates to “Better out,” underscoring its ultimate goal of positively influencing those who enter its oversight. Like Norway, it emphasizes dynamic security and high staff-to-inmate ratios. Sweden’s three-year recidivism rate of 41 percent is less impressive than Norway’s, but still far superior to that of the U.S. and most other countries.

“From an inmate perspective, I’m adamant that it works,” Gillå says. “Both from a human rights standpoint and in terms of rehabilitation and reintegration.”

For years since their prisons established a successful blueprint, international visitors, including Hyatt and his students, have gone to Norway and Sweden to understand what makes their systems effective. Something similar is now happening in Little Scandinavia, which has hosted judges, prosecutors, educators, and politicians, as well as corrections officials from seven states that are members of the Prison Violence Consortium, also funded in part by Arnold Ventures and aimed at understanding the causes and effects of prison violence. The Missouri Department of Corrections sent staff and researchers to Chester for a week last year to study Little Scandinavia and is now developing a unit that will share some of its fundamental concepts, Hyatt says.

While there are meaningful differences between the U.S. and its Nordic counterparts, Andersen says that shouldn’t stop American prisons from emulating their most transformative principles.

“Many people travel to Scandinavia, see these nice-looking prisons, and think, ‘We can’t do this,’” she says. “But if you focus on that you lose the main point. You can still treat people in a different way — even if the place is big, even if it’s grimy, even if it’s old. You can still relate to each other and work together.”

Look in the Mirror

There’s a story Gillå likes to tell about the relationship between inmates and the people who oversee their confinement. A repeat offender returned to the same Swedish prison for the third time, preparing to serve another lengthy sentence that would put his total stay near 27 years. When the prison’s governor asked if he was getting tired of it, he turned the question back on her. How long had she been at the prison, he asked. Thirty-two years, she responded. “Look at you,” he said. “You’ve been here longer than I have.” Their positions within the prison may have been different, but they shared the same environment.

The harsh conditions inside American prisons aren’t detrimental only to inmates; officers bear the weight too. Research has shown that 25 percent of corrections workers have depression, more than three times the national average, while 27 percent experience PTSD, at least twice the rate of U.S. veterans. Suicide rates are nearly 40 percent greater than for the rest of the working-age population, and life expectancy is just 59 years, 15 years below the national average.

To that end, the researchers studying Little Scandinavia are as interested in the welfare of prison employees as they are in the health and well-being of those they oversee. With less noise, more comfortable residents, and better relationships among everyone involved, officers are benefiting. There has been just one incident of note in the two years since the unit filled out — a disagreement this June between two men that escalated but stopped short of being a serious event after staff and residents intervened. One of the men was removed from the unit and has since returned without issue. Otherwise, there has been no violence whatsoever, a stark contrast to the rest of the prison, Hyatt notes. The number of incidents of serious misconduct is also meaningfully lower than in the broader prison, he says.

One of the unit’s pups / Photograph by Rachel Wisniewski

In addition to the relational benefits of dynamic security, the increased staffing ratio puts officers in a better position to address issues that arise. “Even the best officers can only handle so much,” Richie, one of the Original 6, says. The changes, though, go even deeper than that.

Tyler Karasinski, who has been working at Chester for more than six years, was skeptical that Little Scandinavia would work, even if he wanted to believe in the idea. But after making the trip to Norway in 2019 and sticking with the unit since it opened, he’s been convinced. Working in Little Scandinavia has allowed him to eat more healthfully and exercise more, just like the residents. For a while, he was exercising regularly while at work, performing CrossFit-style workouts with Eliezer right in the middle of the block. “He’s my guy, almost a right hand,” says Karasinski, who has lost 85 pounds, part of a “Biggest Loser” challenge throughout the unit that’s seen several residents lose nearly 100 pounds. He credits Little Scandinavia for the change.

The unit isn’t perfect, Karasinski acknowledges. It’s still prison, after all. But the staff are happier, and he now feels good about coming to work every day. He used to be a “lock them up and throw away the key” kind of guy, he says. Now, though, he sees things differently. “We can do a hell of a lot better on the inside trying to change these guys,” he says. “It’s better for us and it’s better for them.”

A Transformational Approach

There may be nothing else in the U.S. quite like Little Scandinavia, but Nordic-style reforms are slowly catching on.

Inspired by a visit to Norway, North Dakota’s prison system began emphasizing dynamic security and rethinking its policies and philosophies. The changes led to a 74 percent reduction in the use of solitary confinement and improvements in the health of residents and staff.

Oregon, following the Nordic model, began a pilot project aimed at reducing isolation and improving the health of those with serious mental illness, part of an effort to reform the state’s use of solitary confinement.

Washington included $12.7 million in its budget to hire 52 new staff in an effort to introduce more humane treatment to its prisons. Like North Dakota and Oregon, it is part of the Amend program, run out of the University of California San Francisco, which aims to change prison culture with Scandinavian concepts.

Few reforms have reverberated as widely as those proposed by California Governor Gavin Newsom, who wants to turn San Quentin, one of the country’s oldest and most notorious prisons, into a center for rehabilitation and a last stop before reentry. The California Model, as the state calls it, was designed based on Norwegian principles. It aims to transform San Quentin by the end of 2025.

When SCI Chester reimagined Charlie Alpha with these same ideas in mind, conventional thinking would have anticipated chaos. But it never came. Instead, the changes have brought order to the lives of residents and staff. As he contemplates the project’s impact, Jordan Hyatt is already thinking about where it could lead next. He wants it to serve as a foundation for future reforms, in Pennsylvania and beyond. What could a similar unit focused on lifers accomplish, he wonders, or one for women, or for those about to exit this chapter of their lives and enter the uncertain future?

“It’s evident that this is something that works,” says State Representative Ben Waxman, D-Philadelphia. “But it doesn’t just work. It’s a transformational approach to how we think about prisons.”

Waxman acknowledges that the future of this program and others like it is as much a question of resources as anything else. Beyond the money spent to spruce up Little Scandinavia, the ongoing cost to maintain it is limited to the increased expense of staffing three officers at a time — and the opportunity cost of housing 64 fewer men than other units do. The daily cost per resident in Little Scandinavia is $2 higher than the prison’s overall average of $190.

But, as Waxman pointed out this June in a letter to Governor Josh Shapiro and the DOC’s Harry, reducing recidivism is “economically prudent,” in addition to its obvious social benefits. The letter, signed by 29 other state representatives, urged the continued funding and expansion of Little Scandinavia.

A Taste of the Outside

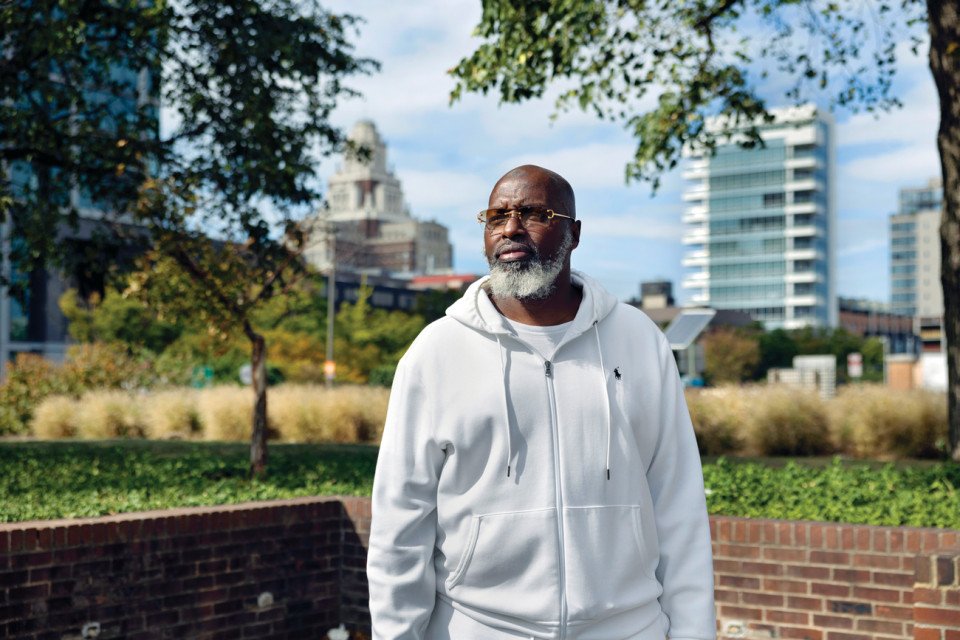

Bowman, in September in Philadelphia / Photograph by Rachel Wisniewski

On the day he was released from prison, Amir Bowman’s family took him out to a restaurant to welcome him home. He has three living children — a son died while he was incarcerated — and six grandkids. They were joined by old friends, and it was a busy scene. One of his daughters ordered him a celebratory meal: steak and lobster. When the food came, everyone turned to see how he’d react to his first taste of something special in 34 years.

“It wasn’t a big thing to me,” he says. In Little Scandinavia, he’d eaten pan-seared steak and baked lobster. He’d learned to cook at the side of some of the unit’s staff, expanding on what his mother had taught him so many years ago. When he mentioned in passing that he’d never tried crawfish, an officer bought and cooked some for him, then showed him how to eat them. The interaction has stuck in his mind ever since. So the steak, the lobster, they weren’t life-changing.

“It was just a meal to me,” he says, “but it was the ambience. It was a meal outside.”

Bowman now works at the Philadelphia Anti-Drug Anti-Violence Network, canvassing the Strawberry Mansion neighborhood where he grew up to share his story in hopes that it might keep someone else from experiencing what he did. He helps mediate disputes and visits victims of gun violence to offer wound kits and assistance lining up care. He discusses with them the anger they might be feeling, the desire for retribution, and urges them toward a better path. In honor of his son he’s building a nonprofit, Just Better Men, focused on helping adolescents through adversity.

This summer, Bowman went back to Little Scandinavia to talk to the men there. The support he received on the unit helped him hit the ground running when he left, even though he spent most of his time there thinking that day would never come. He had help getting his driver’s license set up and his credit established and lining up a job. He wanted to let the men know there’s something there for them on the outside, and that they were in a place that could help them grasp it.

“This is just a taste of what you can get,” he told them. “If you enjoy this, imagine if you get back into society.”

Some already are. Justin, Boogs’s proud owner, earned an associate’s degree in liberal arts at Eastern University while inside and is planning on a bachelor’s in psychology as soon as he’s able. He also got his carpentry license inside and has been using the higher pay scale for Little Scandinavia residents to send money home. (The DOC’s minimum wage is typically 23 cents an hour — an astonishingly low rate. Even the comparatively generous $2.52 maximum allowed for the unit’s members is one-third of minimum wage.)

“I have a life to live,” Justin says of his anticipated release. “I took 15 years of my own life.”

I hope it spreads like wildfire.” — Paige Devane, contact officer at SCI Chester

Amon, who moved into Little Scandinavia in June, considers the unit to be “something special” within the DOC. The pervasive stress that followed him for three years has dissipated. In its place, he says, he’s been given a stepping stone for his reentry, which he expects this fall. He wants to be another success story, like Bowman, a testament that the approach works. “To me,” he says, “it’s healing the offender.”

For Devane, one of the few officers who witnessed Bowman’s entire journey through Little Scandinavia, seeing him return with his head held high was poignant. She says it shows the potential for the unit to make meaningful change in residents’ lives and to “plant seeds of positivity.” For now, there may be nothing else quite like it in the country, but she wants that to change.

“I hope it spreads like wildfire,” she says.

In at least one way, it already has. The aquarium that once entranced Bowman with its tranquil water is no longer unique within Chester. Inspired by its calming presence, the prison has introduced several more in the past couple of years, populating other units and corners of the building. There are now four fish tanks throughout the prison, each one carrying a small piece of Little Scandinavia with it.

Published as “How to Build a Better Prison” in the November 2024 issue of Philadelphia magazine.