Jailing Johnny Doc Won’t Solve Philly Corruption. Here’s What Will

Neither laws nor politicians nor high-profile convictions will change the entrenched culture here. The only way to stop Philadelphia corruption is for citizens like you and me to band together and say "enough!"

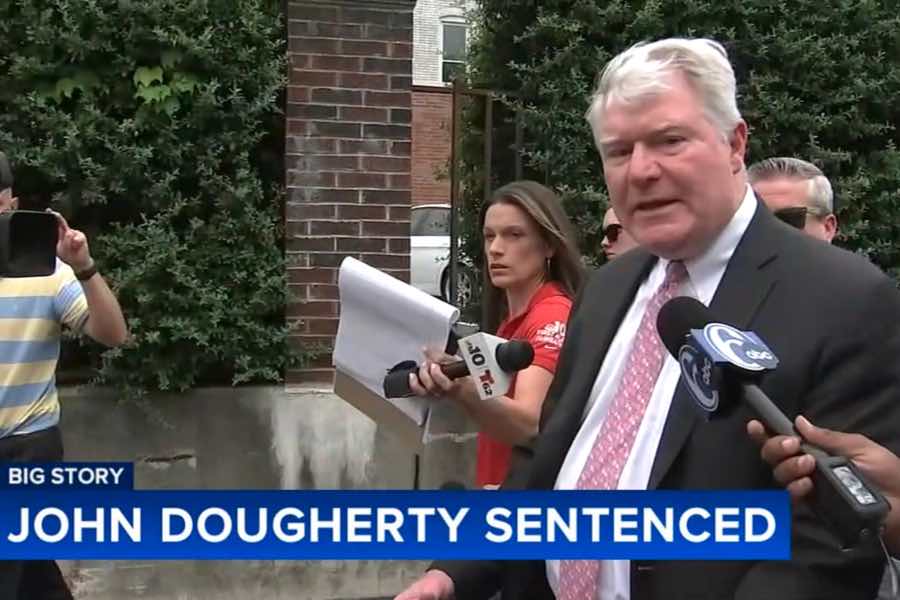

John “Johnny Doc” Dougherty talks to the media after the sentencing for his corruption convictions / Image courtesy of 6ABC

Former labor leader John Dougherty, once one of the most influential public figures in Philadelphia, was just sentenced to spend six years in federal prison for bribing a City Councilmember and embezzling from his union. Dougherty’s sentencing came nearly eight years after FBI agents raided his home and offices. That raid brought to light a corruption investigation that resulted in his conviction along with many of his associates, including a Philadelphia City Councilmember. Dougherty’s investigation, indictment, trial, and conviction showed the public how power is abused and how influence is peddled in Philadelphia. But anyone who thought that this high-profile case might bring about important changes in law or attitudes here might as well have been wishing for an end to our sweltering summers.

In other cities, corruption scandals led directly to legal reforms and significant public rebukes for corruptors. That has not been the case here. It’s always shady in Philadelphia with a chance of waste, fraud, and abuse. The occasional outbursts of sunlight and transparency are always followed by another corrupt storm.

Today, corruption is consented to — through action and inaction by so many in our hyper-connected town. And it costs so much to run a city so poorly. To move Philadelphia into a better future, we must change a culture of corruption. We must implement key anticorruption reforms so we can best address the city’s challenges.

In my 2023 book, Philadelphia, Corrupt and Consenting, I detail the city’s history of corruption and show how it threatens our future. I tell the story of the Dougherty investigation. I discuss the roots, effects, and reasons for corruption’s persistence. And I place our current issues into perspective. In the book, I also make recommendations for making positive change. I encourage everyone who knows that we deserve a better Philadelphia to read the book. Then review its recommendations and join the effort to stop consenting to the corruption that holds Philadelphia back.

To make change for the better, we must understand certain things.

- We need to learn to recognize corruption when we see it. We are on the lookout for overt shakedowns or passing envelopes of cash to bribe seekers. But Philadelphia corruption generally consists of officials doing favors for friends and subverting the work of government to benefit special interests.

- Arguing about whether corruption in Philadelphia is worse or better than it previously was is counterproductive. Asserting that today’s corruption is different from that of the past does not reduce its cost or blunt its other damaging effects today.

- Norms, laws and accepted standards change. What was once an everyday practice can become stigmatized, even demonized, so we cannot count on laws written decades ago to solve these problems.

- We cannot leave the fight against corruption up to a few reform actors or a single reform moment. Each of us needs to want our city to function systematically and properly for everyone more than we want to know someone who can get something done for us. And we cannot stop the fight after any small victory is won.

John Dougherty is the latest Philadelphia power broker who has followed a well-trod path from prominence to prison. If history is a guide, he will not be the last.

Ultimately, it is not enough to change rules or laws to fight corruption. We need to confront our culture of corruption and stop enabling corruptors with our silent consent. We must remember to vote and, when we do, think about corruption. The defining characteristic of Philadelphia corruption is its collegiality. We are all so closely connected to each other. This makes us reluctant to call out bad behavior by anyone who is “one of us.” If we cannot stand against those who engage in corrupt activities because too many ties bind us together, then we need to organize a different “us” to oppose corruption. An anticorruption movement could split from those who do wrong by the city — and those who enable their misdeeds. Then, if we refuse to consent to more corruption, we can create the thriving city that Philadelphians deserve.

Brett Mandel is a writer, consultant, and former city official active in reform politics in Philadelphia.