Meet the Man Who’s Making Philly’s Waterfront … Cool?

For decades, the Delaware River waterfront was a development nightmare: empty lots, decaying infrastructure, poor usage. Joe Forkin has a completely different plan.

Joe Forkin at the site of the future Penn’s Landing Park on the Delaware River waterfront / Photograph by Stevie Chris

For the past 60 years, Penn’s Landing has been a place where big plans go to die.

In the early 1960s, the City of Philadelphia sought to redevelop the land, smartly concluding that the area, situated between the theoretically desirable waterfront and historic Old City, should have something nice. So it’s a considerable irony that the park bearing William Penn’s name — to the extent that a barren slab of concrete can reasonably be called a “park” — represents the spiritual opposite of Penn’s urban-design impulse. A “Green Countrie Towne” this is not. If William Penn arrived in Philly today and saw Penn’s Landing, he might well turn back.

That initial plan for Penn’s Landing, which is actually man-made infill along the Delaware River where there used to be a row of piers, called for 500,000 square feet of office space, including a 30-story tower, a science research park, and a 2,150-spot parking garage, all intended to open in time for the Bicentennial in 1976. The plan had just one problem: No developer ever materialized. Undeterred, the city proposed a new plan in the early ’70s. This one — which would have had double the square footage and included apartments, restaurants, a museum, and a comparably modest 1,110 parking spaces — fell victim to the same fate: no developer. A decade later, the city tried yet again, coming up with a never-realized proposal for a 17-story office tower, a 35-story apartment building, and a hotel. “Before the project could start, there was a city election, and the administration changed,” Penn professor Witold Rybczynski wrote in a journal article summarizing the various development failures.

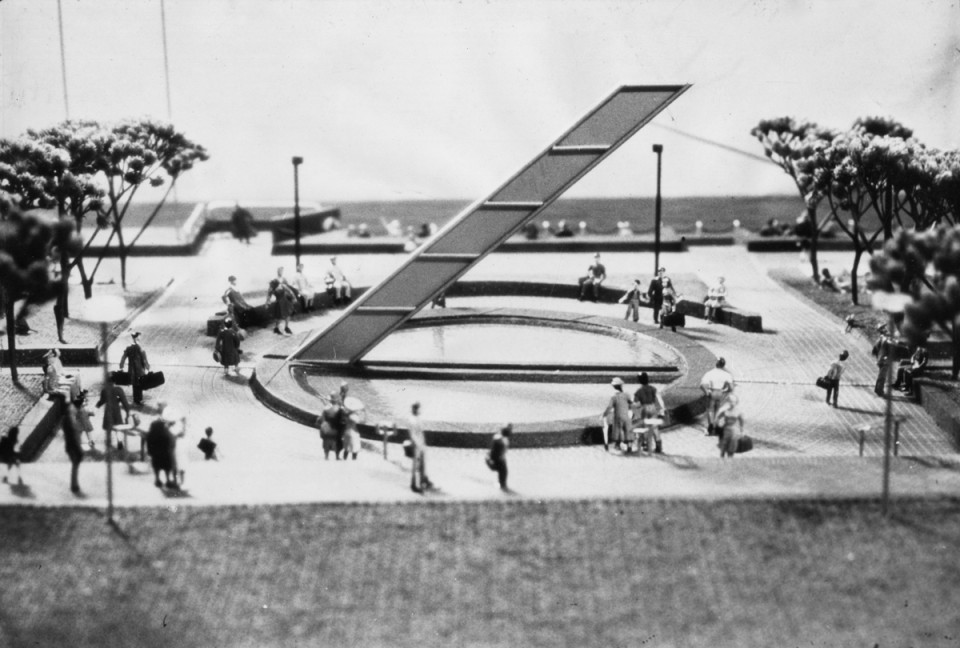

A fountain shaped like a sundial that was part of the early-’70s plan for Penn’s Landing / Photograph via George D. McDowell Philadelphia Evening Bulletin Photographs/Temple University Libraries, Special Collections Research Center

What we now think of as Penn’s Landing wasn’t created until 1986. Having failed to produce any development on the plot of waterfront, the city erected the Great Plaza as a kind of civic gathering place. (An 800-room hotel and retail were also planned but — wait for it — never built.) For many years, Penn’s Landing and the Great Plaza have fulfilled their function as spaces for watching Fourth of July fireworks or going ice-skating in the winter. But urban planners and public officials have always wanted something more from Penn’s Landing, which has produced spectacular failure after spectacular failure and, in classic Philadelphia fashion, no fewer than two major corruption scandals.

In 1986, a City Councilman named Leland Beloff was arrested, along with his connection in the Mafia, for trying to extort $1 million from Willard Rouse, the developer who broke the Billy Penn height barrier with One Liberty Place and was to build at Penn’s Landing, in exchange for passing legislation that would advance the project. (Rouse ended up walking away from the project three years later, mere months before he was scheduled to break ground.) In the late 1990s, during the Ed Rendell administration, developer Simon Property Group tried to build a shopping mall alongside what was billed as an “intricately landscaped parking garage.” Also planned was a tram connection to Camden, which had received federal funding and was to deposit travelers directly at the mall. Simon ended up abandoning the project, although not before the tram base, a thick concrete structure resembling a Shinto shrine, was built. That tram base remained standing for the next 18 years, a bracing reminder of the power of heredity: The only structure the sprawling concrete plaza of Penn’s Landing could spawn was another giant piece of concrete.

John Street was next to try to crack the Penn’s Landing code. But in 2005, a close adviser to Street, Leonard Ross, who’d been put in charge of selecting the winning developer, was charged with extortion, having tried to force the developers bidding on the project to make $50,000 campaign contributions to Street. “I wanna make sure all these other guys who wanna … have a shot at it are gonna come to a few of our fund-raisers,’” Ross said on an amusingly incriminating wiretap.

When you look at Penn’s Landing today, the very architecture of the place, devoid of any real construction, evokes a stagnant city, impervious to meaningful change. Or at least, it did. At the moment, there isn’t really a Penn’s Landing. The Great Plaza looks as if it had a bomb dropped on it. Piles of exposed rebar jut out of the ground like the buried ghosts of developments past. Mounds of rubble cover the 12-acre site. Heavy machinery is demolishing any remaining architectural features, one earth-shaking blow at a time.

Demolition and construction at the park site / Photograph by Austin Marsdale for Delaware River Waterfront Corporation

In four years, there will be a park where this rubble lies. Penn’s Landing Park, according to Joe Forkin, president of the Delaware River Waterfront Corporation — the city-affiliated nonprofit in charge of Penn’s Landing — represents one of the largest public infrastructure projects in the City of Philadelphia in at least 60 years: $440 million in all. The park, which will run from Walnut to Chestnut streets above the combined 15 lanes of I-95 and Columbus Boulevard, will create something surprisingly rare in our city of two rivers: a fully uninterrupted pathway to the Delaware waterfront. You’ll be able to walk straight from Old City to the river, blissfully unaware of the cars rumbling beneath you. The concept still makes Forkin giddy. “I can’t believe it’s happening,” he says.

The Delaware River Waterfront Corporation, or DRWC, as it’s known, was formed in 2009 and is tasked with redeveloping not just Penn’s Landing but an entire six-mile stretch of waterfront from Oregon Avenue in the south, where the dominant feature is a long strip of big-box stores including Home Depot and Walmart, to Allegheny Avenue in the north, where the dominant feature is a facility storing hazardous chemicals in ominous silos. For decades, much of the area has been, to put it mildly, absolutely hideous. But Forkin and DRWC, which has a modest $15 million annual budget, have been on a quest to remake the Delaware waterfront into something that’s actually enjoyable. In 2011, DRWC unveiled an incredibly ambitious master plan that called for creating an uninterrupted bike and pedestrian trail along all six miles of DRWC-overseen waterfront, with a park every half-mile, and extending the street grid so it would connect to the waterfront. Quietly and without much fanfare, DRWC has been ticking off items from the list: the construction of Race Street Pier beneath the Ben Franklin Bridge; the Washington Avenue Pier; Pier 68 next to the South Philly Walmart; Cherry Street Pier; a separated bike and pedestrian path along two miles of Columbus Boulevard from Washington Avenue to Spring Garden.

The central idea behind the master plan is that the Delaware River waterfront is simply too unwieldy, too unfriendly, to ever be fixed by one-off developments or rotating political administrations. By creating a sort of archipelago of new public parks, DRWC is betting that our waterfront will become desirable enough to attract private developers, who in turn will create multiple new, vibrant waterfront neighborhoods.

At the center of the plan, both geographically and spiritually, is Penn’s Landing and the new park. Forkin believes the park, which at 12 acres will be twice the size of Rittenhouse Square, “should count as the sixth square of Philadelphia.” In building it, he and DRWC are confronting more than half a century of failures on this plot of land. So it feels appropriate that before Forkin could rebuild Penn’s Landing, he first had to destroy it.

On a gorgeous spring day in April, Forkin peers out at the destruction of Penn’s Landing through a chain-link fence. “Everything’s filling in so much faster than we thought it would,” he says. “We’re probably in year 30 of the plan already in year 12.” Set to be complete in 2028, the park will consist of two sections: a four-acre flat expanse — the part over the highway — where there will be a pavilion for public events, plus the new ice-skating rink, and then, because the city is built 30 feet above the river level, a gently sloping eight-acre portion that will eventually meet the waterfront. “If you’re standing on the edge of this pavilion, it’s going to feel like you’re on a ship, overlooking the river,” Forkin says. If the renderings, full of green pathways, flower gardens and idyllic hills, are even 70 percent of what the park ends up looking like, it will be a stunning piece of land.

Joe Forkin surveys his domain on the Delaware waterfront. / Photograph by Stevie Chris

That Forkin has managed to turn the cap project into a reality so far ahead of schedule is a testament to his leadership. “He’s one of those very important people in the city that are like glue — they keep things together,” says Bill Hankowsky, the former CEO of Liberty Property Trust, who serves on DRWC’s board. Forkin doesn’t particularly like attention, nor would he appreciate being credited for DRWC’s accomplishments. “I would testify in court that that’s not false modesty,” says Matt Ruben, another DRWC board member, who got to know Forkin two decades ago while serving as president of the Northern Liberties Neighborhood Association. “He just gets his fulfillment from things that get done.”

For many years, the quintessential highway modification case was Boston’s Big Dig, which is equal parts success story (removing and burying a major stretch of elevated highway that ran through the heart of the city) and cautionary tale (total cost ballooned from an estimated $2.6 billion in 1982 to $14.8 billion by the time of its completion 25 years later). While highway remediation projects are once again very much in vogue — in March, the Biden administration allocated $3.3 billion to fund projects reconnecting neighborhoods that have been cut off by highways, including Philadelphia’s Chinatown, which got $159 million to cover up a portion of the Vine Street Expressway — the I-95 cap project predates this wave of enthusiasm. Initially, DRWC had even grander plans. “What if we capped everything from Market Street down to Pine Street?” Forkin recalls suggesting to officials from PennDOT. The response: “No, that’s a tunnel. And that’s gonna cost you $6 billion.” So Forkin and DRWC modified their ambitions. “Keeping in the spirit of, ‘Let’s demonstrate something can be done and not preclude something else from happening in the future,’ we said one block,” Forkin says, ultimately landing on the stretch from Walnut to Chestnut.

To hear Forkin tell it, the process of getting the cap funded was, considering its magnitude, simple business. DRWC first brought up the cap during the gubernatorial administration of Tom Corbett, though the process didn’t really begin to accelerate until Tom Wolf’s time as governor. Early in Wolf’s first term, Shawn McCaney, the executive director of the William Penn Foundation, met with Wolf to discuss projects the foundation was interested in funding. Wolf was intrigued by the cap but said the state couldn’t commit funds unless the city had a stake in the project as well. In 2015, Forkin met with Jim Kenney, who’d just been elected mayor, and asked if he would commit millions of dollars to the project. “He was like, ‘Yes, I will do it,’’’ Forkin says. “Everything was just” — he mimes a plane taking off with his hand — “whoosh from there.”

Part of the success can be chalked up to fortuitous timing. PennDOT was already (and remains) in the middle of a multibillion-dollar reconstruction and widening of I-95; technically, the cap, along with an extension of the South Street pedestrian bridge to the waterfront instead of its current terminus in a parking lot west of Columbus Boulevard, is part of this broader project. In other words, there was a large pot of money from which DRWC was able to siphon off a couple hundred million dollars for its own purposes. All told, the state, through PennDOT, has committed $329 million to the project, which will fund the actual highway cap. The city’s $90 million, plus $15 million from William Penn and $6 million from other foundations, will pay for the park on top.

Governor Josh Shapiro, State Rep. Mary Isaacson, Joe Forkin, and Mayor Jim Kenney at the September 2023 groundbreaking for Penn’s Landing Park / Photograph by Maria Young for Delaware River Waterfront Corporation

It’s difficult to overstate how much Penn’s Landing Park figures to change Philadelphia. According to a DRWC study, the project, by sparking new development in the area, is expected to have a $1.6 billion economic impact. More important, though, is the change on a psychic level. In other cities that have cleansed themselves of car infrastructure, the before-and-after photos are incomprehensible; it’s as if a magic trick has been performed. Take Millennium Park, which is the home of Chicago’s famous bean sculpture and was built a block from Lake Michigan in 2004. That land used to be an enormous parking lot and rail yards, sunk beneath the city and bounded on four sides by roads. From a bird’s-eye vantage, the plot looked like an open wound in the heart of the city. These days, you would never have any idea, because once such a park is built, it seems so obvious that it becomes impossible to imagine anything else was ever there.

The Penn’s Landing project is unusual in another important way — as an example of Philadelphia dreaming big and actually pulling it off. “In this town, no one believes it until there’s a crane,” Hankowsky jokes. But given the history of non-development at Penn’s Landing, can you really blame us? The project, DRWC board chair Jay Goldstein says, is a “testament to Philadelphia being a more modern city.” For those involved, it’s as much an exorcism as it is a construction project.

At first glance, Forkin may seem an unlikely candidate to reverse the fortunes of Penn’s Landing and the Delaware waterfront. For one thing, he worked at DRWC’s predecessor organization, the widely reviled Penn’s Landing Corporation. Made up almost entirely of politicians and their various appointees, the corporation didn’t open most of its meetings to the public and was beset by inactivity. “It lurched from disaster to disaster,” says Matt Ruben. “It was a train wreck.” Shawn McCaney is no more charitable. “It was unclear what they were doing,” he says. “They certainly weren’t providing visionary leadership for the future of the waterfront.” (Leonard Ross, the corrupt Street adviser, was a board member of the corporation when he was indicted.)

Forkin, who’s 51, with short salt-and-pepper hair, piercing blue eyes, and a delightfully Philly pronunciation of the word “water,” joined the Penn’s Landing Corporation in 1997. He grew up in East Oak Lane and has spent almost his entire life in the city. Other than taking a field trip to Penn’s Landing in grade school and sailing action figures in a creek near his childhood home, he had no particular connection to the waterfront growing up. (These days, he lives right along the waterfront, near the Glen Foerd mansion in Torresdale, with his wife and three teenage kids.) Nor did he have any special background in development or city planning. He majored in communication at Holy Family University, got a master’s degree in English communications at Arcadia University, and had been working at an investment firm, training to be a financial adviser. “I absolutely hated it — hated everything about it,” he says. During grad school, he occasionally worked construction jobs, and with that experience, he managed to land a job as the Penn’s Landing Corporation’s director of operations.

In order for a plan like this to be implemented, it has to be able to span multiple political cycles. And it’s critically important to have that buy-in. You can’t change on a whim.” — Joe Forkin

Forkin describes the waterfront of that era as a “postindustrial, disjointed, privately owned mess.” This was during the Ed Rendell administration, when any new development was considered better than the status quo. That philosophy carried over to the Street years, when in addition to the never-ending quest to develop Penn’s Landing, a host of other humongous projects were planned for the waterfront, including a Philadelphia World Trade Center and a $300 million Trump Tower. “The real estate market in Philadelphia was going crazy,” Ruben says. “The dot-com bubble burst in the early 2000s, so tons of capital needed somewhere else to go, and it flooded into real estate.” By 2007, there were 15 different high-rise towers planned for the waterfront — of which just one was built.

During his time at the Penn’s Landing Corporation, Forkin worked on projects, like the hulking, boxy, auto-centric Simon proposal for a mall, that he would laugh out of the room were they proposed today. “Looking back on it now, from an urban-planning perspective, you’re like, ‘Man, that was terrible,’” he says. But this provided its own education of a sort: Penn’s Landing Corporation was a useful guide for how not to do things. In addition to the poor urban planning, Forkin saw firsthand the pitfalls of a board made up of politicians. “In order for a plan like this to be implemented, it has to be able to span multiple political cycles. And it’s critically important to have that buy-in,” he says. “You can’t change on a whim.”

By the time of the Street-era corruption scandal in 2005, a professor in Penn’s design school, Harris Steinberg, was growing exasperated with what the politicians were coming up with — or not coming up with — for the waterfront. (He calls the Simon mall project “a truly anti-urban plan that left many of us in the urban-planning community aghast.”) Adding to the sense of despair was the revelation that Harrisburg was legalizing casinos, with two slated for Philadelphia, both along the Delaware River, in then-Councilman Frank DiCicco’s district.

A rendering of Penn’s Landing Park from the south / Hargreaves Jones and KieranTimberlake

It seemed like a bad joke: Philly couldn’t build much of anything on its waterfront, and now it was being forced by the state to swallow two casino projects that many people in the neighborhoods didn’t even want. (Only one of the casinos, Rivers, originally called SugarHouse, in Fishtown, got built.) DiCicco and McCaney, from William Penn, hatched a plan to counteract the bad development by coming up with an official civic vision for the waterfront and tapped Steinberg to be its leader. DiCicco managed to convince Street, who’d abandoned his initial Penn’s Landing plans, to support the initiative, and the mayor signed an executive order establishing an advisory group made up of 45 different stakeholders — including representatives of 15 different community groups — who would meet to share what they wanted the waterfront to look like. “It would be not business as usual in Philadelphia,” Steinberg recalls. “The press would be involved, and it would be citizen-driven.”

Steinberg was preoccupied with one main question: “How do you repair the city by building back to the river and then allow for future generations to fill it out?” Some 4,000 people participated in the process, which wasn’t without controversy. “We had tension between longshoremen about the future of the working waterfront, between casino gambling, battles over property rights,” Steinberg says. “It was a hotly contested strip of land.” (On the day he presented the final plan at the Convention Center in 2007, he recalls, a giant inflatable union rat was stationed outside the door.) But the usual entrenched interests didn’t manage to sink the plan — a fact Steinberg attributes to the “civic forcefield” he was able to create by partnering with the Inquirer, the William Penn Foundation, and the Penn design school. Such collaboration, he says, was “antithetical to how Philadelphia did things.”

Community engagement is often the thing that stops projects from getting built. But Steinberg managed to manufacture consent with a skillful bit of diffraction: To avoid endless arguments over specific land uses, like casinos or shipping, he sought to frame the discussion around the more thematic “principles for any type of development along the waterfront” — things like block size, building scale, pedestrian friendliness. “Uses change over time,” Steinberg says. His focus was on “long-term city form.”

The final plan, enshrined in a 237-page document titled “A Civic Vision for the Central Delaware,” outlined a range of changes to the waterfront: covering a portion of I-95 and extending the street grid to the river, creating the continuous waterfront trail, increasing the number of parks. Matt Ruben reverently calls this the “Old Testament” — the founding document that shaped what would come later in the master plan.

But how to actually turn a civic vision into a reality? The plan had its doubters. Craig Schelter, head of a group representing private property owners, was quoted in the Inquirer calling it “overly aspirational” and saying there was no “reasonable expectation” it could be carried out. Even the authors of the civic vision themselves acknowledged that “it is challenging because it defies Philadelphia to aim high, change old habits and seize the opportunity to reestablish itself as a leading city of the world.” Steinberg and his team came up with 10 key points needed to realize the plan. At the top of the list: Kill the Penn’s Landing Corporation.

Michael Nutter had just been elected, and as a good-government reformer keen to pour bleach on the stain of corruption created by the Street administration, he was more than happy to get rid of the corporation. He managed to convince its members to vote to disband it, and DRWC was born.

In its master plan, DRWC framed the waterfront as a kind of Gordian knot: “Public spaces cannot exist on the waterfront without new private development, and private development will not happen on the waterfront without quality public spaces as amenities.” So where to begin? For DRWC, the answer was with public space — build that, and the private development would follow.

Philadelphia wasn’t unique in wanting to redevelop its waterfront. Cities across the country had been undertaking similar projects — among them New York City’s transformation of piers into parks along the Hudson River around Chelsea and San Francisco’s Embarcadero. In New York, though, the city either owned or purchased all the land it intended to redevelop into parkland, and in San Francisco, an earthquake destroyed the highway running along the Embarcadero’s waterfront. DRWC, on the other hand, controlled just 10 percent of the land covered by the master plan. It had neither the financial might of New York nor the happy coincidence of a natural disaster knocking out the offending chunk of highway.

DRWC’s first president, Tom Corcoran, who had previously overseen the redevelopment of Camden’s waterfront, liked to say he was focused on hitting singles and doubles — small projects that would serve as proof of concept and, just as critically, as proof of competence. For its first major project, DRWC spent $7 million on Race Street Pier, transforming a dilapidated municipal pier into a landscaped park, lined with trees, where today you can take yoga classes. The organization followed that up with Washington Avenue Pier, Pier 68, and Spruce Street Harbor Park, a summer pop-up space with hammocks, beer, and vendors serving food out of shipping containers.

Land Buoy, a 55-foot-tall sculpture by artist Jody Pinto, fabricated by Salter Spiral Stair, at Washington Avenue Pier. / Photograph by Douglas Bovitt for Delaware River Waterfront Corporation

Despite its work on city infrastructure projects, DRWC is not technically a city agency, but rather an independent nonprofit. As far as quasi-governmental organizations go, DRWC is particularly self-sufficient. While its capital projects are funded through a mix of tax dollars and foundation grants, its daily operations — including trash pickup and landscaping — are completely sustained by the revenue it receives through things like rent and programming in its parks. “We operate like this little city,” Forkin says.

In 2017, Corcoran retired, and Forkin, taking over as DRWC president, set out to make progress on the waterfront trail. Because DRWC owns so little waterfront land, Forkin had to accumulate individual parcels through painstaking negotiations with each individual landholder, sometimes for as little as 300 feet at a time. “It makes it so much more fun,” Forkin says, completely earnestly. “Land assembly is underrated!” Many landowners aren’t keen on surrendering a slice of their property to a public trail, but Forkin derives considerable pleasure in winning wars of attrition: “People would come to you and say, ‘I’ll never sell this to you.’ And next thing you turn around, you have a trail running through their property,” he says, laughing. The trail currently runs uninterrupted from the South Philly Walmart to Penn Treaty Park in Fishtown.

One of Forkin’s skills is his way of making everyone feel that he likes them — a legitimate asset in his line of work, where potential adversaries, from intractable community groups to developers, abound. He manages to accomplish this without revealing much about himself. It takes running into Lavelle Young, a DRWC vice president who has known him for 25 years and is among his closest friends, to learn that Forkin is a hyper-competitive sports fan who used to play pickup basketball every Tuesday night with a group of DRWC co-workers. He once injured a co-worker’s knee diving for a football.

That tenacity has clearly served Forkin well over the course of his piecemeal waterfront-trail negotiations, and it also came in handy in 2018, when developer Bart Blatstein tried to build a Wawa with a gas station on the waterfront. Forkin was stupefied — there was already a gas station right across the street. And DRWC had managed to get the city to pass special zoning regulations along the waterfront, prohibiting uses it deemed incompatible with its vision. One of these was gas stations. “The community did not want it there,” Forkin says. Neither did he. But Blatstein didn’t seem to care. “We couldn’t break through to reason,” Forkin says; he and DRWC eventually wound up in court, where they won. (Blatstein didn’t respond to an interview request.)

Although Forkin spent the first two decades of his time on the waterfront as a behind-the-scenes operations type, he’s developed a knack for development ideas of his own. Turning a chunk of unused land along the waterfront into Spruce Street Harbor Park? That was Forkin’s brainstorm. The park, which debuted in 2014, drew more than 850,000 visitors in its first year. The idea to transform Cherry Street Pier, which used to serve as DRWC’s parking lot, into a mixed-use public space also came from Forkin. “Joe is very smart, and he’s also quite creative,” says Hankowksy, the former Liberty Property Trust CEO. “It’s rare to find both.” The development also felt like a confirmation of Forkin’s credo: Create public space even at the price of some convenience for your own organization.

Cherry Street Pier / Photograph by Society Hill Films for Delaware River Waterfront Corporation

Thanks to its unique structure and community buy-in, DRWC has for most of the past decade been wildly successful hitting its singles and doubles. It has also benefitted from the fact that its mandate resides entirely within the confines of one City Council district — one whose leadership, first with Frank DiCicco and now with Mark Squilla, has been a vocal supporter of the plan. (To see what can happen when a plan bisects two districts, look no further than the Frankenstein-ish design of the new Washington Avenue, where protected bike lanes disappear and car lanes increase west of Broad Street, thanks to Kenyatta Johnson using councilmanic prerogative to veto the years-in-the-making changes to the road.)

Eventually, though, the master plan, with its proposed I-95 cap park, requires hitting some home runs. If DRWC started off in the minor leagues, it’s now been called up to the majors. “I think at the very beginning, people would have said we were crazy to try to accomplish what’s set out in that vision,” says McCaney, from William Penn. “But it’s mostly happening.”

There is a second nine-figure development project taking place right now along the Delaware waterfront. A 15-minute walk north of Penn’s Landing, Forkin stands next to a giant mound of dirt atop which a backhoe is parked precariously. “Make sure the emergency brake works,” jokes Charlie Houder, the developer responsible for said pile of dirt and backhoe. Houder and his property group, Haverford Properties, are building the Rivermark, a two-building, $200 million residential development with 470 units, on the waterfront at Spring Garden and Delaware Avenue. Houder is giving us a tour of the project, which has been more than 10 years in the making and is set to open in July.

Wearing a checkered shirt and construction boots, Houder marches around to the rear of the buildings. “This site sits at a really interesting curve in the river,” he says. Look straight across to New Jersey, and you see a calm, undeveloped riverbank. Shift your gaze upriver, and you see the Betsy Ross and Tacony-Palmyra bridges alongside the smokestacks of the former PECO Delaware generating station, another recent redevelopment. Downstream, the mighty Ben Franklin Bridge dominates the foreground, with the Walt Whitman in the distance. Though you’re just 200 feet from Spring Garden Street, the city feels very far away. The project will include a Sprouts grocery store, Houder says, and each building will have a high-end restaurant with waterfront views.

This parcel is one of the few along the Delaware River that are actually controlled by DRWC. The land, which used to be the site of the city’s trash incinerator and auto impound lot — “That’s what we thought of waterfront land,” Houder says — later became the makeshift concert venue known as Festival Pier. It took a decade to restore the land to residential building standards before DRWC could begin soliciting proposals from developers in 2015.

For some developers, working with an organization like DRWC is a reason not to do a project; they like owning their land and doing with it what they will. “The trepidation developers have is, ‘What level of input is an authority like DRWC going to have?’” Houder says. DRWC made no secret of the fact that it wanted to be involved in the process. “You can’t take that step lightly,” Houder adds.

But it quickly became clear to him that DRWC was going to be an asset in the project. For one thing, its board includes legitimate developers and urban planners like Hankowsky and Marilyn Jordan Taylor, the former dean of the design school at Penn. Early in the design phase, Houder met with DRWC to share some provisional renderings of the site. Frequently, these are pro forma meetings where participants look at some pretty pictures and then go along their merry ways. At this meeting, DRWC board members took Houder’s design off the easel and pulled out their pencils to start making notes.

DRWC’s design input can be found throughout the project. Forkin and his team encouraged Houder to space the two buildings extremely far apart — a move that’s usually anathema to developers trying to “maximize the site,” which is to say cover it with as much construction as possible. But spacing the buildings has produced a view corridor from Spring Garden all the way to the water that anyone walking down the street can now appreciate. The buildings will be surrounded by a pathway along the waterfront that’s accessible to the public; Houder says he thinks of the land as a nine-acre park that just happens to have residential and retail construction on it.

Houder, who notes that “Forkin is as much a partner in this project as anybody,” came away so impressed with the way the DRWC chief navigated the various bureaucratic mazes threatening to stall the development — from gaining approval from the Army Corps of Engineers to mitigating the disruption to the endangered Atlantic sturgeon living in the Delaware (population 250) — that he’s come to the conclusion that Forkin might be in the wrong line of work. “I promised him I wouldn’t say this,” Houder says, “but at some point along the line, I said, ‘You should probably run for mayor, and I’d probably run your campaign for you if you did.’”

For Forkin, the Rivermark development serves as a perfect distillation of the DRWC ethos. “It’s good planning, good partnership, and then the confluence of all those things that are important in the master plan,” he says. “Private development, public space, recreational activity, embracing the river.” As we finish the tour, we pass two construction workers on their lunch break, sitting on a pile of wooden beams, hard hats by their sides, staring out at the tranquil river — a rendering of the future right here in the present.

Even with the Rivermark project nearly built, there’s still a staggering amount of empty land along the waterfront. In South Philly, many of these parcels are fenced off, overgrown, seemingly abandoned. Columbus Boulevard dominates the terrain, and it’s hard to imagine a new neighborhood ever coming into existence. To walk along the waterfront trail here is to encounter a series of homeless encampments along a sequence of disintegrating piers strewn with piles of trash: abandoned shopping carts, construction materials, tarps, a gas stove. DRWC excised 40 tons of trash in a recent cleanup.

The more promising stretch of land begins around Washington Avenue. As you walk along this section, set off from the road by a well-manicured, landscaped median, you pass DRWC projects like Cherry and Race Street piers, as well as the private developments of Morgan’s Pier, Dave & Buster’s, and One Water Street, a 2016 development with 250 units. Still, empty tracts of land can be found on almost every block. The reality is that Houder remains an early adopter; the success of his project may well depend on other developers coming in and furthering something that resembles a true neighborhood.

Until very recently, there was every reason to believe that might happen. The Durst Organization, the development firm that co-developed One World Trade Center and had never previously purchased property outside of New York, decided to invest here, gobbling up the piers that currently house Dave & Buster’s and Morgan’s Pier in 2017 as well as a plot of land on Vine Street in 2020. Durst sank $50 million into a planned 26-story, 360-unit apartment building and had finished laying foundation. But in 2022, citing inflation and rising construction costs, it halted construction.

Rendering of the currently paused Durst hotel project on Penn’s Landing / Image courtesy of the Durst Organization

More concerning is the fact that Durst has hit pause on developing DRWC’s other crown-jewel property: the 12 acres on either side of the future Penn’s Landing Park. Back in 2019, DRWC sought bids for the land from developers and ended up picking Durst, which submitted a $2.2 billion plan calling for nearly 2,400 apartment units and a hotel, plus nearly 100,000 square feet of offices and retail. DRWC selected Durst over the 76ers, who had proposed putting their new arena there. That the Sixers, who’d hired DiCicco, the former Councilmember and head of the Zoning Board, as a consultant were skipped over in favor of an out-of-state developer was, in some ways, a sign of how far Penn’s Landing had come. “It’s like a different universe,” says Steinberg. (The Sixers, who now want to build their arena on Market Street, could possibly learn a thing or two from DRWC. “The master plan was designed through a community-input planning process,” says Councilmember Mark Squilla. “The arena project was designed by a developer who said, ‘I have this idea and want to put it here,’ and then we have to react to it. Two very different processes.”)

Now that Durst has paused the Penn’s Landing project, though, the fate of the land seems up in the air yet again. Is history repeating itself? A Durst statement isn’t exactly brimming with confidence: “New development in Philadelphia and nationally remains extremely difficult due to a challenging financial market, high interest rates, and high construction costs. The Durst Organization believes in the significant potential of Philadelphia. We continue to maintain our sites and examine next steps.”

Whatever happens, DRWC still owns the land and could always find a new developer. If the barriers to development at Penn’s Landing were a lack of intentional planning, a corrupt political establishment, a highway cutting off access, and a lack of public space, those problems have mostly been solved.

Forkin isn’t unaccustomed to the occasional defeat. A few years ago, he got started on a plan to reimagine Foglietti Plaza, the other capped portion of I-95, which sits between Spruce and Dock streets. The plaza, which houses multiple war memorials, is a bland brick space that doesn’t get much foot traffic. Forkin rightly intuited that it could be much better and began a neighborhood engagement process, hiring an architect to propose a design. Ultimately, the various memorial groups couldn’t come to an agreement with community members, and Forkin decided to drop the project.

But it hasn’t totally ground to a halt. The Society Hill neighborhood association recently decided to redevelop the plaza on its own, hiring the same architect to resume the design. Once DRWC starts a process, it can prove hard to stop. Forkin, for his part, doesn’t think of the Foglietti episode as a defeat. “Good ideas,” he says, with a hint of mischief and the certainty of someone playing the long game, “never die.”

Published as “The River Warden” in the July 2024 issue of Philadelphia magazine.