Meet the Bad Boy of Philly Antiquities

Main Line native Graham Arader, the notorious collector of only the finest rare maps, art and books, has landed perhaps his greatest acquisition — a collection of rare Bartram drawings. His intention: find a public home for it in Philadelphia. (And just maybe cement his legacy in the process.)

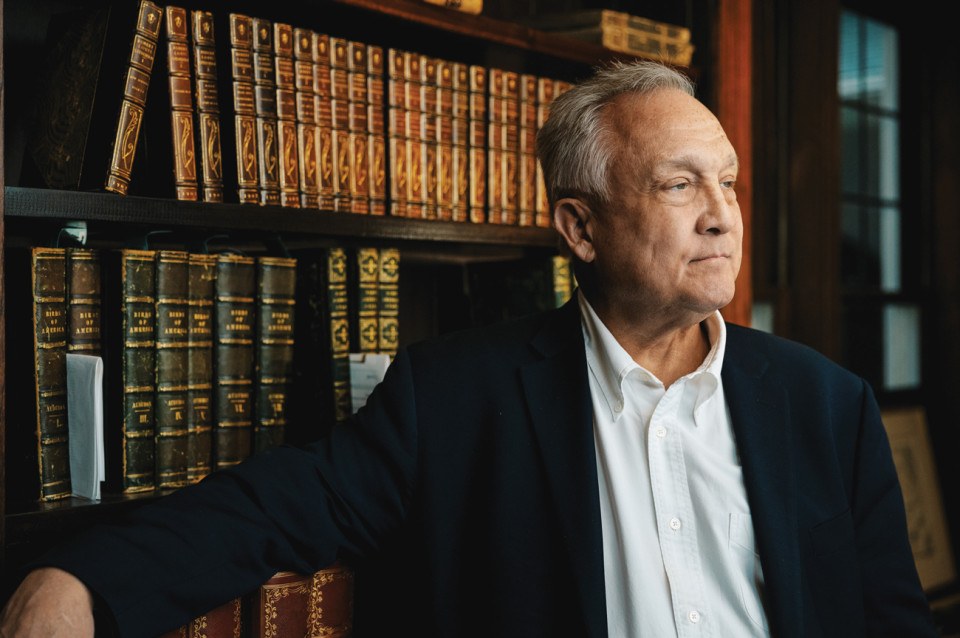

Graham Arader at Ballygomingo. Behind him is the Charles Blaskowitz map that traces the Royal Army’s 1777 pursuit of General George Washington during the American Revolution. / Photography by Justin James Muir

When I find W. Graham Arader III in his stunning 26-room pre-Revolutionary suburban mansion last summer, he’s eating from a clear plastic tub — the kind you find at the salad bar at Giant. It’s 10 a.m., a strange time for what looks like yesterday’s salad. But Arader, perched at his computer, makes it clear: His work as perhaps the most notorious buyer and seller of the world’s rarest antique maps, prints and books is 24/7. “Everyone’s fascinated with Ukraine, right?” he asks, apropos of nothing, initiating our first of a year’s worth of conversations.

Dressed in a faded blue polo shirt with a hole above his belly button and shorts and shoes that look just as comfortable, he readily admits that he buys all his clothes at Walmart. He’s not concerned so much with what he wears as with the appearance of practically everything else he owns, including Ballygomingo, his 1758 expanse off the Gulph Mills exit of the Schuylkill Expressway in King of Prussia. Like his myriad one-of-a-kind possessions, his home has an exquisite provenance: It was once the residence of Isaac Hughes, a lieutenant colonel in the Pennsylvania militia. Arader purchased it in 1977. That was 200 years after, Arader claims, General George Washington’s 11-day stay here before his encampment at Valley Forge. (Historians aren’t certain Washington stayed here, though they have little doubt he stayed somewhere in the vicinity before decamping for Valley Forge.)

Today, mostly, it’s the suburban showplace for Arader Galleries, a retail repository for the world’s best 16th-to-19th-century natural-history lithography and watercolors, maps and important atlases, rare books, prints of the American West, furniture, and other significant Americana. From the glorious double-elephant-folio birds from John James Audubon’s The Birds of America to Lewis and Clark’s landmark journals of Western exploration to the delicate floral engravings of French court painter Pierre Joseph Redouté to period maps of the American Revolution, the collection on display in Arader’s various galleries and properties represents a half-century-plus commitment to acquiring and offering for resale superior works in unrivaled condition.

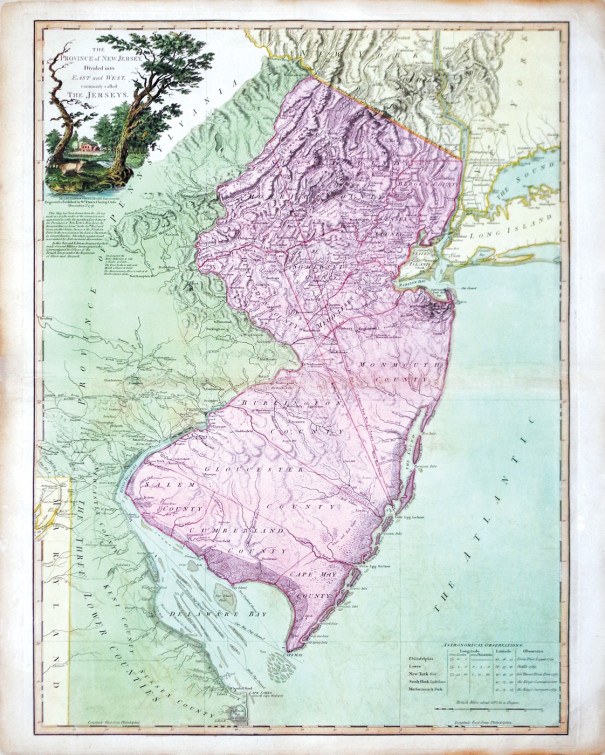

One inked and hand-colored Charles Blaskowitz map hanging in the formal living room — priced at $1.6 million — traces the movement of the Royal Army in pursuit of Washington from its landing at Elk Ferry to Philadelphia, between August and early December 1777. A Great American West oil painting, an 1860s Albert Bierstat of spruces in the Colorado Rockies, is cataloged at $275,000. There’s the circa-1686-’87 manuscript map of Germantown by Francis Daniel Pastorius that may have been William Penn’s own. It lists at $1.26 million. There’s a 1795 William Birch watercolor believed to be the first of New York City after America’s independence (a steal at $250,000). Everything’s a first, or a best. Otherwise, why own it?

“I’m so damn lucky,” says Arader, a lion who’s roared through his field. “I’m largely looking at things that kings were so possessive of, they wouldn’t allow anyone but the highest levels of society to own. And everything’s for sale.”

Over the course of a career that’s been as celebrated as it’s been controversial, Arader has amassed loyal alliances and ardent enemies in the haughty world of antiquities. In his quest to own these artifacts, he’s done, well, whatever he’s felt he’s needed to do. In the process, he’s run afoul of norms in the hidebound collectibles business. The king of his domain, he represents hundreds of thousands of dollars’ worth of hand-selected material culture and a who’s-who list of 32,000 career clients — an ineffable collection of social kin. But at 73, he’s poised for reflection. If he’s guarded about the press, well, he’s been burned in the past. Yet he seems to want me here to help him contemplate the legacy he’ll leave behind. His industry is in flux, with its values increasingly volatile, a middle class that’s vanishing, and the challenge of attracting younger collectors, who may have an interest in older things but not the income to buy them. Still, Arader says he reaches the masses, “probably selling 30 items a month for less than $30 each. You don’t have to be rich to enjoy the story of the last 500 years.”

A capstone to his illustrious career could be cemented by partnering with an appropriate and willing Philadelphia cultural institution to permanently house his latest conquest, a storybook acquisition of several long-vaulted volumes of what may be the finest 18th-century hand-colored botanical drawings in existence. The books are the first major collection of work cataloging the flora and fauna of the Americas. Included are the 51 earliest watercolors by William Bartram (1739-1823), the celebrated Kingsessing-born botanist, ornithologist, natural historian and explorer and son of John, the namesake of Bartram’s Garden.

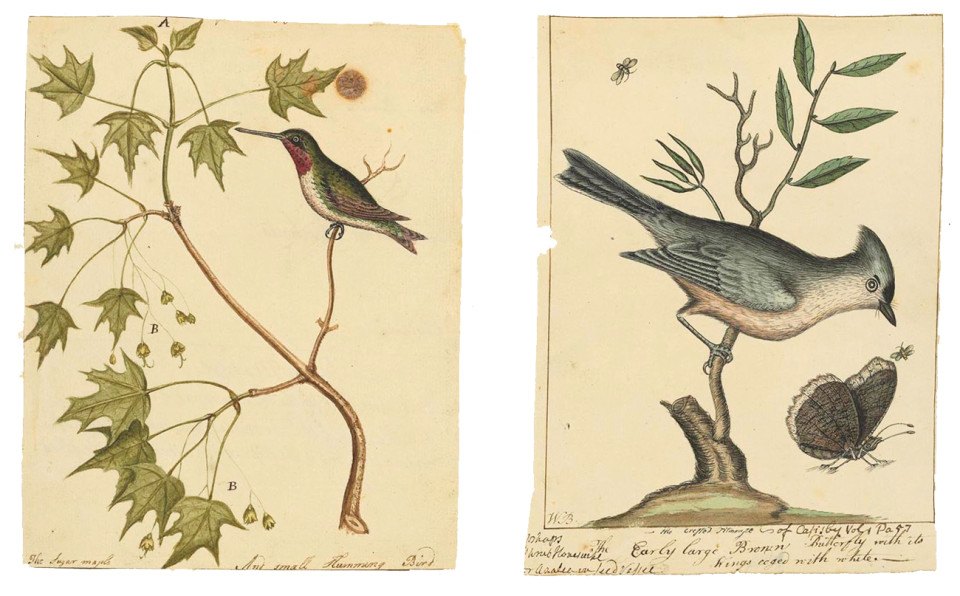

Two pieces by William Bartram from the just-acquired Collinson Corpus

Its arrival here has been delayed for more than four years by export hurdles in England, but now, Arader is ready to offer up “the world’s most important 18th-century natural-history corpus that relates to the Americas” for what he feels is a modest buy-in. (Though “modest” is subjective.) He’s looking to find the collection a home at an institution here. It’s a grand gesture, on one hand, but it’s also one made complicated by Arader’s trademark mix of business savvy and, perhaps, ego. If he succeeds, the sale could help make him — and his hometown — whole. The Bartrams, all drawn in Philadelphia during the botanist’s teen years between 1750 and 1760, would come home, and Arader could make amends for past sins, both within the industry and at home: a penitence. “My only wrongdoing [as it pertains to Philadelphia] is that I Ieft,” insists Arader, who initially invested in his hometown in the late ’70s, decamped to live in New York City in 1994, and returned in earnest in 2017 to buy and restore additional Philadelphia-area properties.

In at least one departure from the sort of past practice that’s earned him foes — and maybe as an indication that he’s learned from his mistakes — Arader has vowed there’s “zero chance” he’d break up the collection’s sets to capitalize on what he estimates as a $60 million piecemeal value if sold to individual clients. (“Breaking books,” as it’s called in the trade when a collection or volume is broken up and sold as individual pieces or pages, is among the practices Arader has engaged in that have earned him scorn among peers.) “I’d burn in hell for that,” Arader says of the prospect of breaking this particular collection. “This corpus documents how native plants became known. The entire Bartram story is compelling and very, very connected to Philadelphia. Gardening is a passion in Philadelphia. So is the Quaker view of the importance of the natural world, and Bartram having written the first great American travel book. It’s a very Philadelphia story.”

Arader, pronounced “Uh-raider,” is a Philadelphia story himself. The eldest of four privileged children raised in Radnor, he was born to succeed. His mother, Jean, painted. His father, Walter, an investment banker, also ran a printing company and was Pennsylvania’s Secretary of Commerce under Governor Milton Shapp. A beekeeper and gardener, Walter served charities and sat on dozens of boards, including those of the University of Pennsylvania and the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. During the mid-1960s, Walter began collecting sea charts, then maps from famous atlases, which also attracted young Graham.

Graham grew up on the tennis courts at the Merion Cricket Club and the Racquet Club of Philadelphia, then the squash courts at the Hill School in Pottstown after eight years at Holy Child School at Rosemont. He spent most of a post-grad year in England at the prestigious Canford School, buying maps for a nascent father-son partnership. Then, at Yale as an economics major, he began selling them from his dorm room, refreshing inventory on squash trips to England. He played number one singles for three years, was an All-American and on the All-Ivy team, and was captain in his senior year. When not swinging a racket, he was in the Sterling Memorial Library and the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, which together housed thousands of rare maps. When he graduated in 1973, he won Yale’s Adrian Van Sinderen prize, an honor given to seniors and sophomores most likely to “stimulate book collecting among undergraduates, to encourage book buying, book owning and book reading both as a hobby, and as a fundamental part of the educational process.”

Summers at home were more primal. Long taken with plants of all kinds, Graham started a tree-surgery business and later merged this passion into a senior thesis that compared the barriers of entry into the Connecticut and Pennsylvania tree-surgery industries. No surprise, he profited from it, too, demonstrating an emerging knack for entrepreneurism: He ran ads in tree-surgery journals that proclaimed: “Buy the Yale report on tree surgeons.” He says he sold 500 copies for $25 apiece.

He might have remained a tree surgeon if not for two chainsaw cuts still evident above his left knee; it fell to his brother, Chris, to grow Arader Tree Service in West Conshohocken. The chainsaw “slips,” as Graham dubs them, led to a $150,000 loan from his father, who likely sensed that this son had a brighter future as a collector than as an arborist. The loan came with instructions: “Go buy expensive things.” Arader began conquering antiques shows, traveling in a station wagon with a hollowed-out cargo area for stacking prints.

When map prices, which had increased through the late ’70s, slowed, he expanded into books, prints and paintings. Initially, his books focused on racquet sports. On one trip to England while still in college, he paid $250 for a 16th-century Italian book by Antonio Scaino — the first ever on tennis. Three months later, Arader sold it in Philadelphia for $2,500.

Philadelphia from Camden, by Nicolino Caylo

Sales of works by iconic naturalist Audubon, though, carried Arader from the start. For years, he sold best between Pittsburgh and Denver and Chicago and Dallas — in regions where, he says, “stingy people are ostracized.” Philadelphia, by contrast, is a “thin market.” “Before I started, Philadelphia was already richly saturated,” he explains. “There was already so much in homes. No one needed more. They were spoiled here.”

All the while, as a leading industry insider, Arader invented and improvised, benefiting from his moneyed background and the 20-year mentorship of Stanley Marcus, founder of Neiman Marcus. “He taught me to be a merchant,” he says.

He infamously employed a tactic called “syndication” in which he sold shares in prominent collections to potential buyers ahead of an auction, then pooled that money to bolster his buying power. This method allowed him to, for example, corner the market for Redouté watercolors. Redouté (1759-1840), whose chief patron after the French Revolution was the Empress Joséphine, was a court artist for Marie Antoinette and arguably the world’s best flower illustrator — the Audubon of flora.

In 1985, via syndication — a “degree of hocus-pocus” within legality, according to an exhaustive and emasculating Arader profile in the November 30, 1987, issue of the New Yorker — he bought 468 of the 486 original watercolors from Redouté’s Les Liliacées. An Arader syndicate baffled rival bidders reported to include the Bibliotèque Nationale de France, the Getty Museum, and the Morgan Library & Museum. Arader bought the grouping with a single unchallenged bid of $5.5 million (after Sotheby’s 10 percent buyer’s fee), though he said he could have spent $8.8 million.

Arader, whom the magazine Art & Auction once called “the self-anointed emperor of the auction room” and “the man the book trade loves to hate,” doesn’t lack enemies. He’s shined a black light on the industry — he claims he’s helped imprison eight people for selling him stolen goods and that he’s served as an FBI informant for 40 years — and the industry has reflected it back on him. Maybe that’s why he often aggressively thrusts his index finger or stabs downward with his fist — like a judge with a gavel in his hand — for emphasis. “Anyone with an IQ over 80 knows to avoid me if they’re wicked,” he says.

Detractors, including former friends, speak softly about him, or not at all. They say he does and gets whatever he wants, whatever the cost. One industry icon who wouldn’t be identified says, “He’s Donald Trump.” Another, fellow Yale alum and former employee Hugh Kennedy, who reportedly based his 1996 novel Original Color on Arader (fictional Nelson Albright, “the boss from hell” per the book jacket and “a megalomaniac dealer” in one review), like others, didn’t return interview requests.

When Arader was unceremoniously booted from the Antiquarian Booksellers Association of America in 1983 — guess it didn’t care he’d won that Yale book prize — he brought a failed federal lawsuit for readmission, declaring that his expulsion infringed on his right to trade. The ABAA didn’t like that he returned a book (actually a five-volume set of John Gould hummingbirds) to a fellow member-dealer by parcel post, and, according to the New Yorker, said Arader didn’t “further friendly relations and a cooperative spirit among members” — one of its stated purposes. Current ABAA executive director Susan Benne will only say, “These matters occurred long before I began working for the ABAA.” For his part, Arader believes the ABAA didn’t like that he’d part out books or collections and adds that the organization reacted “mostly in jealousy.”

Graham arader commands an audience as well as George Washington did. Wherever he is, there’s a daily 11 a.m. EST staff conference call. On one particular day last July, he’s pushed the power huddle to noon. He’s onstage, a king in his castle. In attendance at Ballygomingo are Luke Shepard, Sam Serruya and Athen Schaper, a trio of interns from Lower Merion High who are taking part in a sort-of “be-like-Graham” summer camp, along with Chad Henneberry, chair of Lower Merion’s history department. Henneberry arrived in Arader World in the fall of 2022 in search of the Holy Grail — that Blaskowitz map. A Revolutionary War re-enactor for the British side, he marvels at its detailed documentation. Prepared for British Commander General William Howe, the map falls just short of tracking Washington’s stay at or near Ballygomingo and the encampment at Valley Forge. “It might indicate that the British didn’t then know where Washington’s army was,” Henneberry suggests. “They did then lose the war.”

As part of crafting his legacy, Arader is invested in building future interest in his industry — the focus of the internship. It’s a free internship, but Arader says that once the program receives certification, it will cost participants around $3,000. (“A bargain,” Arader maintains.) The youngest of Arader’s seven children, Alex, is of high-school age — he’ll start at Franklin & Marshall College in the fall. Arader also has seven grandchildren, the youngest born in March, so he knows kids today aren’t clamoring to get into curatorship. Still, he hopes the alumni of his internship will seek to become the directors of institutions like Independence National Historical Park and Longwood Gardens and not just lawyers or surgeons.

“Years ago, Steve Jobs” — a longtime client — “personally told me that he was making a machine that would steal the minds of kids,” Arader says. “He said that it was evil, and that there was nothing good or kind about it. He succeeded.”

The Province of New Jersey Divided Into East and West Commonly Called the Jerseys by William Faden

Watching him, his computer, and that unfinished salad at today’s conference call, the interns and I learn there’s a challenge to being Graham Arader, or at least to being in such a competitive, high-stakes, changing industry. We’re standing-room-only, 10 or so of us cramming into his small office. Tom Quinn, his CFO and partner, sits on the hallway floor. Book guru Ken Hook is pacing in a side room. Both charming and cantankerous, Graham is reading emails and responding to voiced and emailed questions, making assignments, offering opinions, and keeping up with online bids. (“Most of those emails were notifications he’d been outbid,” Serruya tells me later.)

Today’s focus: Graham Arader’s four rock-solid tenets to landing a sale. Number one: Get to know the client and allow the client to get to know you — a 12-to-14-year endeavor, sometimes. Number two: Establish that the inventory of interest exists and is free and clear to change hands. Number three: Tell the client, “You can own it.” Number four: Tell the client, “I think you should own it.”

Arader quickly turns the session into a fast-paced game show. “Fifty-dollar cash bonus to anyone who can tell me any of the 20 things I did to establish a common relationship with [client and L.A. financier] James Bailey that allowed him to spend $34,000 [on two Audubons] with me without even asking for a discount,” he begins.

Bailey is his daughter Jo’s decade-long client, and her prolonged efforts satisfied step one but hadn’t netted an end result. “In 10 or 12 years, you never sold him anything, correct? No sales?” her father asks.

“I don’t think you had anything to do with it,” she snaps back on speakerphone from California, where she runs Arader Galleries in St. Helena. “He was just ready to buy Audubons.”

“That’s not what I want to hear,” he says. “You’re not getting $50. You’re missing the point. What did I do to open him up, to allow him to put down his defenses? Maddie” — that’s Maddie Bashant, an archival and gallery assistant — “can you do it for $50?”

“You found that you had friends in common,” she offers.

“You also discussed Harvard” — where Bailey swam — “and Yale and that rivalry,” pipes in 30-year colleague Alison Petretti, Arader’s natural-history stalwart, who’s curating the Bartram-infused tomes that are in New York. “Because his boy was having trouble playing basketball, you suggested he play squash.”

“You’re so impressive!” Arader commends her. “And there were about 25 more things we had in common.” Among them: that they both have Asian wives; Bo-in Arader is Korean, and Bailey’s married to actress and model Devon Edwenna Aoki, who is of Japanese descent. “That knocked off five years right away,” crows Arader.

Plate CCI Canada Goose, by John James Audubon

On to new subjects, as Arader bounces between emails again with a raucous rapidity. (Michael Zinman, an associate with whom he maintains a rocky relationship, once told the New Yorker he’s never met anyone who lives “stream of consciousness” quite like Arader.)

“What did we pay for those John Vickers Painter Audubons?” he asks regarding a set of 404 aquatints that took 15 years of negotiations and $2.3 million to buy from descendants of the esteemed stamp collector and banker from Cleveland. “Alison, get me your opinion of them.”

Jeffrey Stern, a bookseller in England, has English Civil War broadsides dating from 1642 to 1651 that were printed for the Parliament. “They’re pretty obscure, but $7,500 is a ridiculous price,” says Arader, who passes on them, figuring they’re too expensive to purchase and then sell at a profit.

It’s all about value, or, to be more precise, perceived value. Arader Galleries does $22 million in annual sales, though in a recent blog, Arader asserted that he’s only recently become flush — antiques-world lingo for having the cash to purchase additional assets. He’s still an annual presence at 10 antiques shows (including the Winterthur Delaware Antiques Show in November and the Philadelphia Show in April at the Philadelphia Art Museum), but he used to exhibit at 40. There were also once Arader galleries in Chicago, Houston, San Francisco and Atlanta. The galleries in Philadelphia and New York remain, but they’re modern-day retail dinosaurs despite their obscene real estate value. Arader’s location in the city at 1308 Walnut is the former site of Charles Sessler’s iconic antiquarian bookstore. In Manhattan, Arader’s business inhabits a 1903 Beaux Arts townhouse at 1016 Madison Avenue. It briefly listed in the late 2000s for $75 million, and Arader says he rejected a $60 million offer. His neighbor is Michael Bloomberg.

“The internet rules,” says Arader, adding that he anticipated the need for contraction and adaptation once museums began losing government funding, the world at large began dominating collecting, and all buyers started shopping online. “Walk-in storefronts don’t work anymore in any business.”

That’s why he added bimonthly online auctions recently, essentially becoming his own Christie’s and Sotheby’s. These sales average 200 lots and consistently command some $1.5 million total. Uniquely, for one or two auctions per year, 20 percent of every hammer price goes to a charity of the buyer’s choice.

Arader once employed 60 staff members but has downsized to 35 — a powerful, experienced, connected contingent that includes Lori E. Cohen, his longest-tenured business partner, who steers everything Philly-centric. “She’s survived as a 40-year partner among very selfish men — men who wanted to grab the stag by the throat and watch themselves as they kill it,” he says of Cohen, a board member for the Historical Society of Pennsylvania who, like many in this buttoned-up world, wouldn’t be interviewed for this story. “She’s intelligent, patient, and responsible for huge results.”

For help with period furniture — a recently renewed fascination for Arader because purchase prices have plummeted — he employs highly sought Lancaster-based furniture historian Phil Zimmerman. After Arader acquires furniture, Zimmerman conducts meticulous on-site evaluations and authentication reports of, for example, a circa-1760 Pennsylvania Chippendale walnut secretary desk. Period to Ballygomingo, it once had a purchase price of $350,000. Arader bought it for $28,000.

Much of Arader’s furniture consists of large Philadelphia secretary desks that sit inside Ballygomingo like miniature Manhattan skyscrapers. “Furniture is a love story amongst really stubborn people,” Arader says of the folks who still try to deal in it. On one hand, he’s compelled to buy and sell. On another, he seems increasingly drawn to build something lasting, to hold onto these acquisitions. “I want to look at the pieces, enjoy them, learn from them — and maybe build another Winterthur.”

Book expert Hook’s office is a step down from the mahogany-paneled Dechert library — named for Philadelphia attorney and former owner Robert Dechert. One of Ballymingo’s recently renovated rooms, it’s made entirely of built-in bookcases. “Whatever it is, we’ve got it,” says Hook, who sold Arader a set of Pennsylvania Dutch books when they first met three years ago, then was offered a part-time job. (Arader collects people, too.) Hook, in his mid-70s at the time, accepted. “This has been a godsend to me, really,” he says. “What we have here in every room is not a facsimile. It’s not a second map. It’s a first edition, and it’s worth hundreds of thousands of dollars. It’s like a museum.”

A museum. That’s imperative if those prized Bartrams are to return home, or, at the least, go to a private donor in conjunction with one. Arader’s willing to part with the large cache of extraordinary works, including the Bartram windfall, but in exchange, he’s seeking a $15 million buy-in — 25 percent of what he says is its fair market value — to cover his investment and expenses. He also wants an institution’s academic commitment to producing 5,000 copies of an accompanying catalogue raisonné — a critical, comprehensive, annotated book — that he’ll pay up to $300,000 to publish. By Arader’s calculations, if those are sold at $300 each, the partner could reap $1.5 million, or 10 percent, back on the investment.

In total, the corpus consists of three volumes. There are two volumes with original Mark Catesby watercolors and his unique, annotated proof engravings. They were published in London in 1731 and 1743 and titled The Natural History of Carolina, Florida and the Bahama Islands. The first major study devoted to the botany and zoology of the Americas, it was likely a subscriber set sent as a thank-you to Peter Collinson (1694-1768), Catesby’s chief patron. The third volume was arranged by Collinson and is known as “A Commonplace Book.” It includes the 51 Bartram watercolors as well as illustrations from renowned botanical watercolorist Georg Ehret and George Edwards, the father of British ornithology, among others. This specific assemblage includes a frontispiece drawing of the Philadelphia garden of John Bartram. The pen-and-ink drawing of the first botanical garden in America is thought to be by the great nurseryman himself. It’s titled “A Draught of John Bartram’s House and Garden as it appears from the River. Sent to P Collinson.” It’s dated 1758, as is Ballygomingo, and is chipping badly, Arader has disbound, framed and hung the sketch, but it goes with the body when sold.

Catesby (1683-1749) was among the first naturalists to explore southeastern North America. As such, he was a major player in an intricate transatlantic exchange of plants, animals and information among scientists, explorers, and horticulturalists who included Collinson and John Bartram (1699-1777), William’s father. A cloth merchant and a botanist, Collinson, as a friendly favor, sold Bartram’s seeds to Britain’s best. They soon wanted illustrations to accompany the seeds, and a young William emerged.

The works landed with grandson Charles Streynsham Collinson and were purchased by Alymer Bourke Lambert in 1834, then by Edward Stanley Smith, the 13th Earl of Derby, in 1842. They were passed down to the 19th and current Earl of Derby, Edward Stanley. (An aside: These are the Stanleys for whom ice hockey’s Stanley Cup is named.) Through Christie’s, which acted as a broker, Arader made the purchase in 2019 for $4 million. At the time, the volumes were valued at £2.5 million, or $3.75 million, by the British government. Arader believes they’re worth much more.

But now that they’re here, does anyone other than Graham Arader want them?

Among the likely local destinations that could make sense are the American Philosophical Society (founded with the help of John Bartram), the Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University (where William was an early member), the University of Pennsylvania, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, and Bartram’s Garden. (The Natural History Museum in London has Bartram’s mid-career watercolors; the Philosophical Society has his end-of-career collection.)

Thus far, the response Arader has received from the institutions he has approached has been universal: We love it. We should have it — but we can’t afford it. “It’s true,” Arader submits. “That’s why it was easy to leave Philadelphia. I couldn’t make sales. Now, frankly, there aren’t enough generous people here to support the 100 institutions that made Philadelphia the city it is. There’s not enough wealth left in the city.”

Among the potential collection recipients, Robert Peck, the curator of art and artifacts and senior fellow at the Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University — the nation’s oldest natural-history museum, founded in 1812 — conveys the common mantra and day-to-day dilemma: “It would be wonderful if this could come to Philadelphia,” he says, having personally seen the volumes in England and since Arader’s acquisition of them. “This would be the right place for it, and we would certainly welcome the collection with open arms and give it a proper home. Unfortunately, we don’t have an acquisition budget to purchase it. Graham may be hard-pressed to find any institution in the country that can afford it.”

For Arader, who has made such a point of returning to his roots, his legacy is on the line. He’s been using a $7 million legal settlement he won’t discuss to purchase and improve additional historic properties in Upper Merion to complement Ballygomingo. Reestablishing himself in the area has been bumpy. Perhaps he’s been viewed for too long as a taker, not a giver. Even when he appeared at an Upper Merion Township supervisors’ meeting three years ago to gift an Audubon, his generosity was met with dubiousness. “He wanted the Audubon used educationally,” says board chair Tina Garzillo, who, like me, was an Arader holiday party guest last season. “We said, ‘We’re governors. We’re not in the business of education, but how about the school district?’ From what I understand, the [Upper Merion] school board told him they wouldn’t even know what to do with it.” Tamara Thomas Smith, the current superintendent of the Upper Merion Area School District, confirms that the gift was not accepted, likely over concerns about managing the valuable artwork.

Graham Arader

Still, others have feasted on Arader’s philanthropy. The Philosophical Society accepted five rare botanical watercolors valued at $1.75 million in 2022. Universities nationwide, including Northwestern, the University of South Carolina, and Marymount College, are using Arader gifts in excess of $100 million for student study in Renaissance genres and his personal favorites, like binomial nomenclature and Swedish biologist Carl Linnaeus. He says he’s topped $400 million in art donations. So why is this corpus different? Why not give this away, too? “I need funds to run my business and to purchase inventory,” he says matter-of-factly. “I’m not rich enough to make this a 100 percent gift.”

So, he still harbors this lingering, incurable need to buy, own, and then sell in order to get the next best thing — and deep down, he knows it. In April, he told me, “God punishes those with too much.” Thirty years ago, Donal O’Brien, a now-deceased five-decade Rockefeller family lawyer and longtime chair of the National Audubon Society, first humiliated Arader into altruism. “He said, ‘You stingy son of a bitch, you’re not giving back,’” Arader recalls. Giving back was also part of the suggested cure for his persistent hoarding disorder, diagnosed 10 years ago by Columbia University Medical Center psychiatrist Jeffrey A. Lieberman.

He genuinely seems to mean well. But he’s a businessman, and his bottom line is, well, his bottom line. So, like his industry, he’s at a crossroads — and he isn’t shy in stating that if the city doesn’t step forward, the Collinson corpus could go to “red-hot” Texas. “This will be the greatest thing I ever sold, which just says I’m still a merchant,” Arader says, adding of Philadelphia: “They just can’t make the decision here.”

Drexel’s Peck, who’s known Arader for 40 years and senses that the dealer’s legacy will forever be tied to this collection, predicts the coming debate could replicate the mid-2000s scramble to keep Thomas Eakins’s 1875 painting The Gross Clinic in its rightful home — and away from Arkansas’s Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art. “Philadelphia rose up then and said it had to stay,” he remembers.

Arader would like nothing more. “There’s something about coming back to the place where you were born, this region, that makes me feel so good,” he tells me in a rare moment of quiet contemplation. “You don’t have a full life if you don’t give back.”

Published as “The Bad Boy of Philly Antiquities” in the June 2024 issue of Philadelphia magazine.