72 Years Ago, Philadelphia Made a Huge Mistake

And we’ve been paying for it ever since.

1950s Philly, around the time the city implemented its first business tax / Photograph via Philadelphia Department of Records, courtesy of PhillyHistory.org

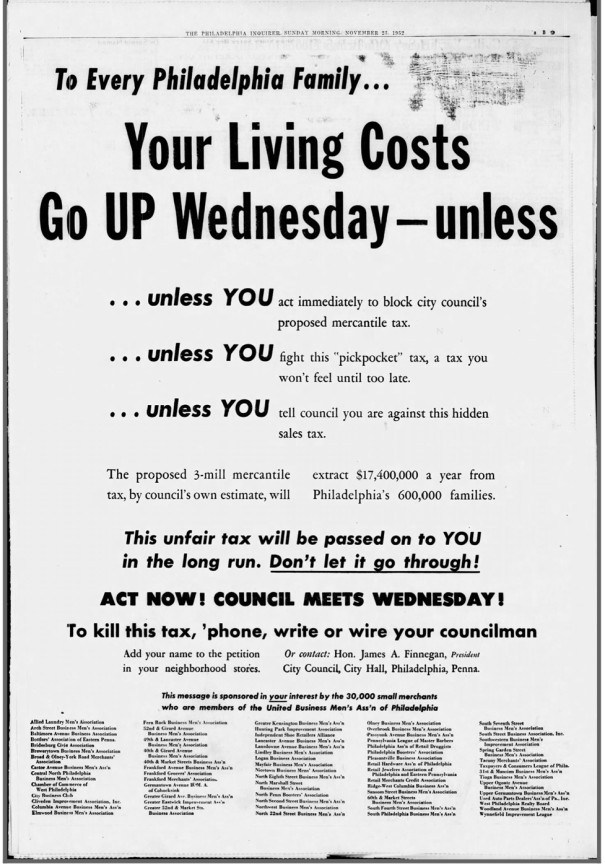

If you picked up a copy of the Inquirer on November 23, 1952, and turned to page 47, here’s what you would have seen: a full page ad making a passionate appeal to Philadelphians.

The ad was signed by several dozen neighborhood merchants associations.

The timing wasn’t accidental. That Wednesday, City Council was scheduled to vote on Mayor Joseph Clark’s first municipal budget. It included a first-ever city tax on businesses — a 3-mill levy that would require businesses to pay a tax of 30 cents for every $100 of gross revenue they brought in.

The ad wasn’t the only sign of opposition. Several Republican and Democratic officials had already spoken out against the proposed tax; the previous week more than 500 business people had flooded into a Council meeting to voice their opposition; and the Inquirer had published a pump-the-brakes editorial, saying the administration hadn’t made the case the new tax was necessary.

Mayor Clark’s argument in favor of the tax was simple. A reformer and the first Democrat elected mayor since the 19th century, Clark wanted to provide better services to Philadelphia citizens while also cleaning up the fiscal shenanigans of previous city officials. Example A of the latter: the previous year, right before the election, the Republican-led Council tried to win the favor of city workers by keeping their salaries the same but reducing their work weeks from 48 hours to 40 hours. It was a change that would cost the city at least $6 million annually in extra staffing — except Council didn’t allocate any additional money for it. Philadelphia needed more revenue to cover those costs and others, Mayor Clark said, and a new tax on business was one way to get it.

But the argument against the new tax was equally straightforward. First, businesses were likely to pass the extra cost onto customers, making living costs for Philadelphia families — as the ad noted — go up. Second, the new tax was on gross revenue, not on profits, which meant even businesses that lost money would have to pay. Finally, and maybe most significantly, the new tax would make Philadelphia a far less appealing place to have a business, which would ultimately cost the city jobs and revenue. Chamber of Commerce president J. Harry LaBrum called it “the worst thing that could happen to Philadelphia. It would chase business away.”

On Wednesday, November 26th, Council took its vote. The new tax passed 12-5.

Seventy-two years later, I’d argue we’re still paying for it.

Nobody likes paying taxes, even though governments can’t operate and cities can’t function without them. The key to success is figuring out who and what to tax — and how much — so that the system is fair and actually creates opportunity for people. This is particularly important on the local level, since it’s easy for people — and businesses — to move if they think taxes are too high.

That was the problem with Philadelphia’s business tax 72 years ago. And though the tax has changed some since then (in 1985, we adopted the current BIRT tax structure, which lowered the levy on gross revenue but added a tax on profits – currently 5.81 percent), it’s still a problem today. Thanks to our high tax rates, private-sector businesses don’t want to be here, which means we struggle to create jobs. And a lack of good-paying private-sector jobs is one of the main reasons behind our low standard of living and high poverty rate.

How bad is the problem? In statistics published by the Inquirer in 2020, Philadelphia ranked below the national average, with a private-sector job growth rate of just 1.6 percent annually. That put us well behind cites like Austin (4.2 percent growth rate); San Francisco (3.5 percent); Seattle (2.6 percent); Detroit (1.9 percent); and Boston (1.8 percent). The key difference between Philly and those cities? The business taxes here are significantly higher.

And things haven’t gotten any better since the pandemic came to an end. In statistics published last year, Philadelphia was in the bottom half of big cities when it came to job growth.

Our high business taxes are arguably the main reason that of the 10 largest employers in Philadelphia, only one — Comcast — is a private-sector company. The other nine are either government-related (the city of Philadelphia; the federal government; the school district; SEPTA) or nonprofits (Penn, CHOP, Temple, Temple Health, Jefferson). None of those organizations pay business taxes.

It’s also one of the reasons the city regularly loses businesses to our own suburbs. Twenty years ago German software company SAP wanted to open a 1,000-person North American headquarters. Philadelphia appeared to be an ideal location — until the company figured out city taxes would cost them an additional $50 million annually. Instead the company chose Newtown Square — only 12 miles away — and today more than 3,300 people work there.

Imagine if those 3,300 employees worked in the city instead. Think about the wage tax revenue we’d earn. Think about the impact on property values and property taxes, since some number of those people would likely want to live in the city, too. Then think about that multiplied by all the other businesses that chose not to locate in the city of Philadelphia.

We’d have so much more opportunity for our residents.

Thanks to action by City Council, the business tax rate has dropped marginally — by a few tenths of a percentage point — in the last couple of years, but it’s time to get much more aggressive. Eliminating the net profits tax over the next 10 years to zero will produce more employment across the city and will provide economic benefits to our economy.

Three-quarters of a century of bad policy is long enough.

Allan Domb served as an at-large member of Philadelphia’s City Council from 2016 to 2022 and is president of Allan Domb Real Estate.