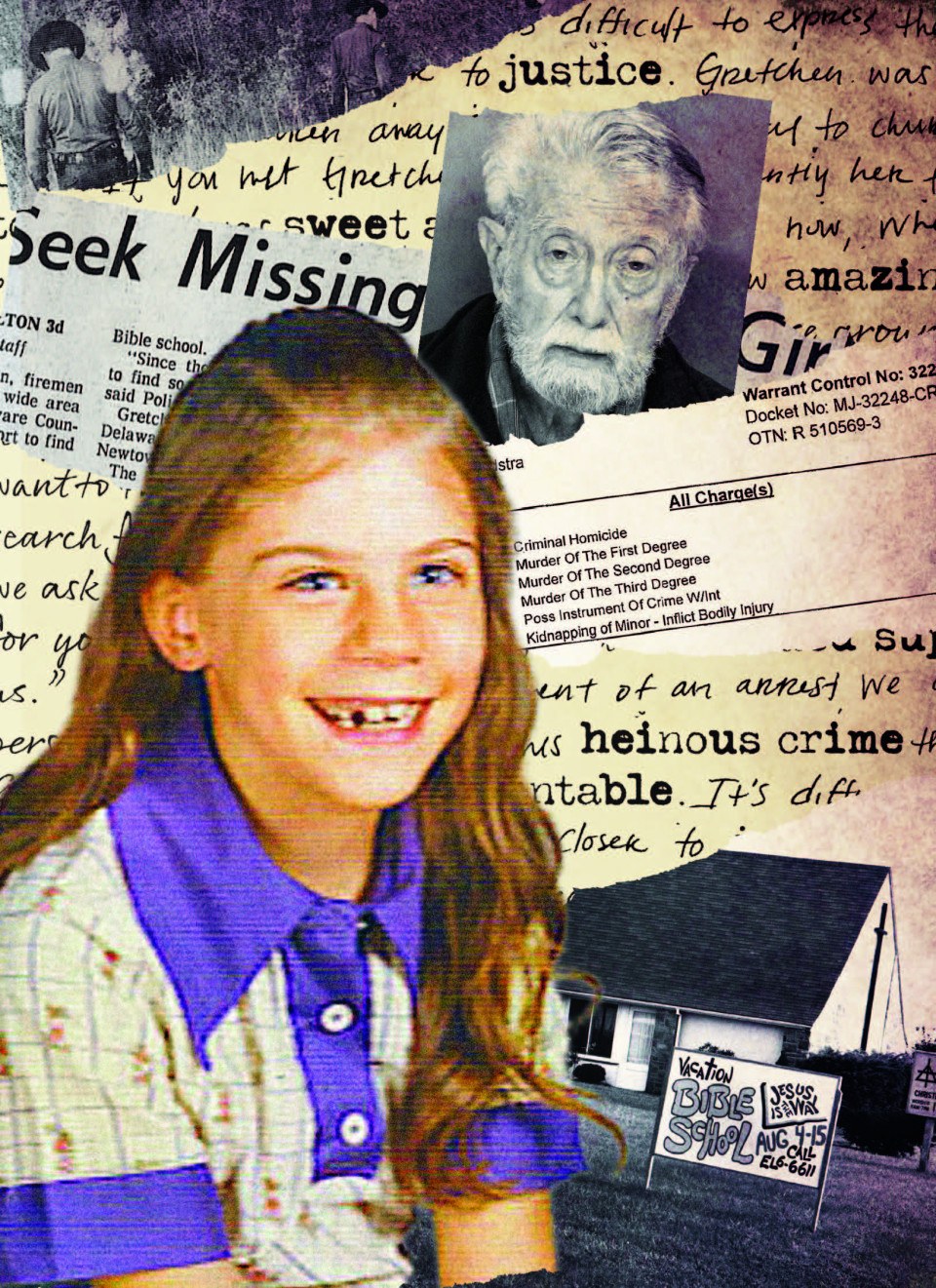

Gretchen Harrington, a Delco Pastor, and the End of Innocence

The inside story of Marple Township’s infamous 50-year-old cold case.

Photo-Illustration by Leticia R. Albano

On Saturday, August 16, 1975, in the pre-dawn hours, a police sergeant in a suburb near Salt Lake City, Utah, pulled over a tan Volkswagen Beetle he deemed suspicious. Inside the car, he found a handsome man in his late 20s, wearing a turtleneck. Upon searching the vehicle, police discovered an ominous assemblage of items that included a ski mask, an ice pick and a pair of handcuffs. Investigators identified that man as Theodore “Ted” Bundy. He later confessed to having killed more than two dozen young women, most of whom were strangers to him.

On that same day in Marple Township, which sits about six miles west of the Philadelphia-Delaware County border, nobody had yet heard of Ted Bundy. There was no social media. Twenty-four-hour news cycles were still 20 years away. And even if those things had existed, authorities hadn’t yet connected Bundy to his horrific trajectory of rape, torture, murder and necrophilia. They were just beginning what would become a lengthy and disturbing investigation into the man. In Marple, police had their own chilling investigation going on.

The day before, eight-year-old Gretchen Harrington had departed her Cape Cod-style home on Lawrence Road, tidy blond pigtails dancing in the summer air, to walk to vacation Bible school. The VBS sessions started at Trinity Christian Reformed Church, about a half-mile up the road. They continued at nearby Broomall Reformed Presbyterian Church. Gretchen’s dad, Harold, had served as pastor there since moving his family from Western Pennsylvania in 1968.

A child walking alone on a sunny summer day in a place like Marple was hardly unusual. Such a thing wasn’t perceived as having even the faintest whiff of risk. This was the 1970s, in a leafy suburb. Kids played freeze tag and sardines and Red Rover outside till all hours. They played on the streets, in the dark and in the woods. They cooled off in Darby Creek, which ran behind Gretchen’s home, without a care in the world. Kids walked to their friends’ houses blocks away, no cell phones or GPS watches to tether them to their parents. There were no bike helmets to be found. Marple was as safe as safe could be. That’s why many longtime Philadelphians moved there in the 1960s.

But Gretchen’s solo excursion actually was unusual for her. On any other day, she’d have been walking to VBS with her two sisters, Zoe and Harriet, known as “Ann.” Gretchen’s sisters were a few years older than her. Walking together was their routine. On this particular day, though, their mom, Ena, was bringing home her newborn baby, Jessyca. And Zoe and Ann opted to stay home and wait for their arrival. Pastor Harrington encouraged Gretchen to go to VBS to keep up her perfect attendance record. So Gretchen was all alone as her father waved goodbye to her. She began her stroll up the hill to Trinity just after 9 a.m.

Later that morning, apparently sometime around 11 a.m., Harold learned that Gretchen had never made it to her destination. He spoke with Trinity’s pastor, David Zandstra, and Zandstra’s wife, Margie, both of whom worked in the VBS program. David Zandstra called the police at Harold’s request. The Harringtons and Zandstras knew each other well. The two families lived close to one another. Both dads were in the same line of work. And both moms filled the stereotypical role of pastor’s wife. One of Zandstra’s daughters was Gretchen’s best friend.

As the sun set that day just before 8 p.m., there was still no sign of Gretchen. Margie brought supper to the Harrington home, where Ena seemed resigned to the fact that she would never see her daughter alive again. “She was just kind of accepting of the fact that [Gretchen] was gone,” Margie said in an interview years later. “I don’t know whether she was just putting on a brave face. I think she was in shock.”

By Saturday, hundreds of people were involved in the search for Gretchen. A Pennsylvania state police helicopter buzzed the area continuously.

Paul Barton, who lived in nearby Newtown Square, heard about the search on his police scanner while he was floating in his backyard pool. He soon drove down to Darby Creek to join a search team. His group combed a grassy hill that’s now the site of a Giant supermarket, a stone’s throw west of the Blue Route, which was under construction at the time.

“There was just this very solemn feeling among all of us who were out there searching,” Barton recalls. “We went out there not knowing what to expect, what we might find. We were looking for something, anything. But we found nothing. Nobody did.”

That Sunday, just two days after the mystery surrounding Gretchen had begun, police called off the large-scale search operation. Investigators had little to go on. The police chief told a local newspaper, “We haven’t got a clue.” The town went into full-blown panic mode. Friends and family members began handing out fliers to passing motorists in the area. The fliers showed Gretchen in her most recent school photo, sporting a missing tooth and a childish grin. So much speculation; so many unanswered questions: Had she run away? Did she drown in the creek? Did a stranger abduct her? Was it somebody she knew?

“A few days after Gretchen disappeared, my mom made me get my hair cut real short so that I would look like a boy. She didn’t want me to stand out with long hair,” recalls Karen Franks Zetterberg, a Bible-school classmate of Gretchen’s who was the same age and lived in the same tightly knit neighborhood. Before Gretchen disappeared, Franks Zetterberg regularly walked to school, her piano lessons and the swim club. But life changed for good following the incident: “I never walked alone anywhere again after that.”

Jim Christaldi, who as a youth delivered newspapers to the Harringtons, speaks fondly of a pre-disappearance childhood in which he and his friends would spend countless hours building forts in the woods, with only the light of the moon. But right after Gretchen vanished, Christaldi, a teenager at the time, found himself in search parties in those same woods, looking for Gretchen — or anything that might have led to her whereabouts. “We were innocent,” he observes. “And this absolutely shattered our innocence.”

All the searching produced no useful clues of any kind. August turned into September. Zoe and Ann Harrington returned to Delaware County Christian School. The other kids at school didn’t talk to them because they didn’t know what to say. September became October. As Halloween decorations began to adorn neighborhood houses, still nothing.

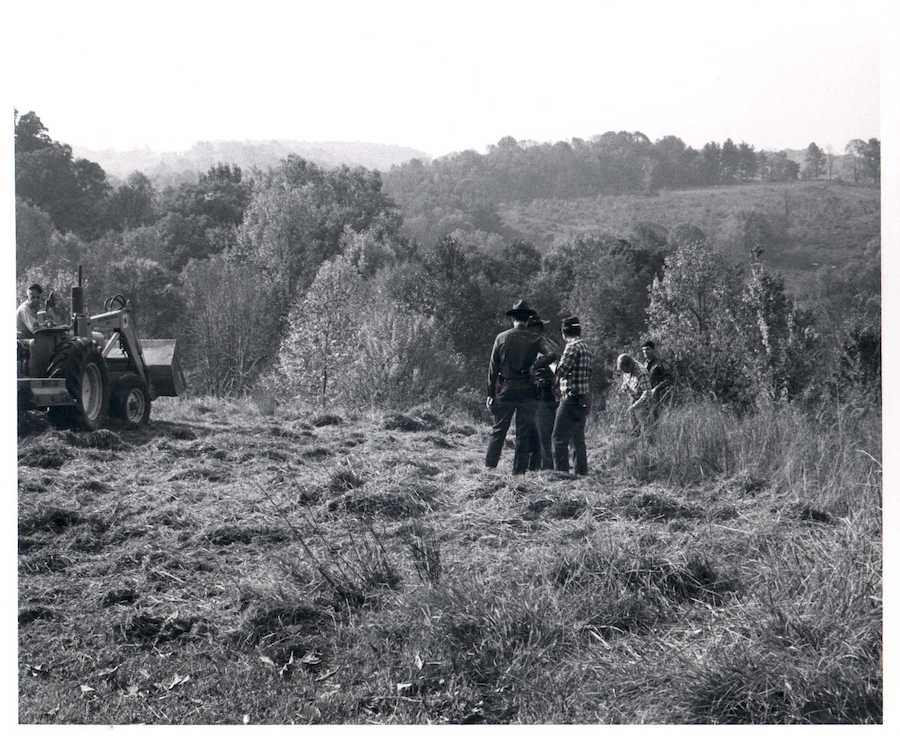

Then, on October 14th, two months after Gretchen walked up that hill, a jogger in Ridley Creek State Park, about 20 minutes from Gretchen’s home, stumbled on skeletonized human remains. At first, he wasn’t sure what he had found — until he saw what was clearly a fingernail. He ran to fetch a park ranger.

Gretchen’s parents confirmed that the distinctive clothing found with the remains was hers — Ena made the girls’ wardrobes by hand. The medical examiner positively identified the body as Gretchen’s using dental records. The manner of death: homicide. The cause: Someone had fractured her skull with multiple vicious blows. Police suspected sexual assault, though the autopsy revealed no evidence of that.

The Sunday after Gretchen’s body was located, Harold took to the pulpit and delivered a heart-wrenching sermon. “Gretchen, with her simple faith in Christ, is free,” he declared. “But her murderer is in terrible bondage. … The world is filled with unspeakable evil because of the wickedness of the human who knows the truth but will not accept it.”

The discovery in the woods led to a new frenzy of activity in the case. Witnesses came forward with reports of men of various descriptions they’d seen in the area where Gretchen was found. Police received numerous tips, some sounding more promising, some completely frivolous.

Investigators looked into a series of potential suspects, including several known sex offenders living in the area. But nothing led to an arrest. And the evidence box at the headquarters of the Marple Township police department, with reel-to-reel-tape interviews, photographs and memoranda packed inside, began collecting dust, as it would for decades to come.

The Marple church where Gretchen Harrington attended VBS and David Zandstra was pastor / Photograph courtesy of the Delaware County District Attorney’s Office

Nick Coffin can’t remember exactly what day it happened, but it was sometime last fall. He was sitting at Marple Township police headquarters — he’s a sergeant — when he heard the voicemail. Naturally, when detectives retire or pass away, other cops inherit their cold cases. In the case of Gretchen Harrington, Coffin became the guy. So when a woman called Marple police last fall and wanted to talk to somebody about Gretchen, her message went to Coffin’s phone.

The woman said she thought she knew who’d murdered Gretchen and talked about an attempted kidnapping around the same time. She also mentioned that she kept a diary in the 1970s in which she recorded some of this information when she was a 10-year-old girl living in Havertown, about three miles east of Marple. The woman still had the diary in her possession all these years later.

Coffin got in touch with Pennsylvania state police. Though the case remained open with the Marple cops because Gretchen had last been seen in their jurisdiction, the state police technically became the lead investigatory agency once the remains were found in the state park. “Besides, I have four detectives in my division,” Coffin notes. “The state police have so many more resources.”

State troopers scheduled an interview with the woman. She is designated in court documents only by her initials, S.F., and “C.I. #1,” the terminology used for a confidential informant. The interview would turn out to be a monumental development in a cold case that had been open for nearly half a century. And monumental developments in decades-old cold cases almost never happen.

The woman told the state troopers that she had been childhood friends with one of the Zandstra daughters. She frequently slept over at their house. During one of those sleepovers, when she was 10, she told the troopers, she awoke in the middle of the night to find Pastor Zandstra touching her groin area. She shifted her position, and he immediately hurried from the room. The next night, he touched her there again, she said. When the girls woke up the following morning, the woman says, she mentioned the dad’s odd behavior to the daughter, and the daughter told her something to the effect of: “He does that sometimes.” When the girl related the incidents to her parents, they told her she wasn’t allowed to sleep over at the Zandstra house anymore. Notably, police believe the incident in question occurred exactly one week before Gretchen vanished.

The woman also told state police about another child in the neighborhood with whom she was friends, a girl named Holly. According to the confidential informant, somebody had attempted to abduct Holly. She wrote the following entry in her diary, which she turned over to the state troopers earlier this year: “Guess what? A man tried to kidnap Holly twice! It’s a secret, so I can’t tell anyone, but I think he might be the one who kidnapped Gretchen. I think it was Mr. Z.” She confirmed to the troopers that the Z stood for Zandstra.

Local police had questioned Zandstra back in 1975, along with a bevy of other people. Some witnesses had said they saw Gretchen outside a car, talking to someone sitting inside, on the morning she disappeared. Some of the descriptions of the car matched one of Zandstra’s. But Zandstra insisted he hadn’t seen Gretchen on the day in question. Bizarrely, though, and in an investigatory gap apparently never explained by Marple police, Zandstra was able to give an accurate and detailed description of the homemade shorts Gretchen was wearing that day — even though he supposedly hadn’t seen her. The original Marple detective in her case died in June of 2020.

This past June, state troopers tracked Zandstra down to a lakefront home in Marietta, Georgia. He and his wife had moved there after he’d retired in the mid-aughts. Zandstra agreed to meet the troopers at the headquarters of the Cobb County police on July 17th.

The troopers questioned Zandstra about Gretchen’s disappearance, and he reiterated to them that he hadn’t seen her that day. Then they revealed the newest allegations to him — that the minister had sexually assaulted his daughter and her best friend.

A criminal complaint filed in Delaware County against Zandstra soon after that meeting states that he immediately admitted to the sexual assaults and to seeing Gretchen the day she went missing. He told the troopers he offered her a ride and that she accepted. But when it became clear VBS wasn’t his destination, Gretchen asked him to take her home. Instead, he said, he took her to a wooded area and demanded that she take off her clothes. She refused. Then he attacked her. He claims he struck her in the head with his fist and that this ended her life. He said he checked for a pulse and believed her to be dead, so he covered her half-naked body with sticks in the woods and went back to his life.

The Pennsylvania state police wouldn’t comment for this story, citing the fact that it’s an open investigation. But Phil Stoddard, a detective in Marietta, Georgia, who sat in on the Zandstra interview, told a TV news crew there that Zandstra was emotionless during his confession to the troopers. (One source of information on the case is a book by Mike Mathis and Joanna Falcone Sullivan, Marple’s Gretchen Harrington Tragedy, published in 2022 by the History Press.)

As of press time, Zandstra was sitting in a Georgia correctional facility, awaiting extradition to Delaware County on charges of kidnapping and homicide. His lawyer didn’t respond to multiple requests for comment.

The area of Ridley Creek State Park where retired pastor David Zandstra has confessed to killing Gretchen Harrington in 1975 / Photograph courtesy of Ridley Creek State Park

As much as Zandstra’s confession brought closure regarding Gretchen’s fate, it also raised a serious question with reverberations from coast to coast: Did this man who has admitted killing one girl and sexually abusing two others have other victims?

Before coming to live in Marple, Zandstra was the pastor of a now-defunct church in Flanders, New Jersey, for several years. While at Trinity, he campaigned against the teaching of sex education in the local school district. Less than a year after Gretchen’s remains were found, he moved his family to a church in Plano, Texas, just outside Dallas, where he led the congregation for seven years.

After that, it was off to the Living Faith Community Church in San Diego until 1990. Zandstra’s final church was in Fairfield, California, a post he retired from in 2005, when he was 65. That’s a lot of years of power and access to the young and vulnerable.

A spokesperson for the Christian Reformed Church in North America, the religious organization under which all of Zandstra’s churches were governed, tells Philly Mag that it knows of no other allegations against Zandstra but is in communication with his previous congregations regarding him and is cooperating fully with law enforcement.

Police in California recently announced that they’re looking into whether Zandstra might have abducted Amanda Nicole “Nikki” Campbell, a four-year-old girl last seen riding her bike alone to a friend’s house in 1991. Zandstra and Campbell lived just minutes from each other. Investigators in Georgia have now collected a DNA sample from Zandstra to potentially aid in investigations of missing persons, sexual assault and murder nationwide.

“The case in Delaware County is getting a ton of attention,” a spokesperson for the Cobb County district attorney told us. “And this is the kind of case where the more people hear about it, the more people could come forward.”

While the Marple community now has some of the answers it’s been seeking for all these decades, many of the residents we spoke to haven’t found peace in this shocking turn of events. It was much easier to believe that some outsider had done this, some deranged itinerant sex offender who had somehow wandered into town, snatched up a young girl, and then disappeared just as quickly, taking his evil with him to whatever unfortunate place he landed next. Instead, police say, it was a respected member of their community, a religious leader with a wife and young girls of his own — a wife who’d brought supper to the family of the girl he’s confessed to murdering the very day he says he killed her.

“Back then, everybody was surprised that Gretchen would get into a car with a stranger,” says Franks Zetterberg, Gretchen’s VBS classmate. “And now to find out that this monster was hiding among us in plain sight all the time — it’s just sickening. We were always taught in church that evil exists in the world. But you don’t really understand evil until something like this happens. We were far too young to learn about evil the way we did.”

Published as “The End of Innocence” in the September 2023 issue of Philadelphia magazine.