The Battle for 76 Place: One Year Later, Where Things Stand With the Sixers’ Controversial Arena Project

The debate over the Sixers’ potential move from the Sports Complex to Center City has become a standoff involving Philly’s most powerful interests. Will any of them be happy with the outcome?

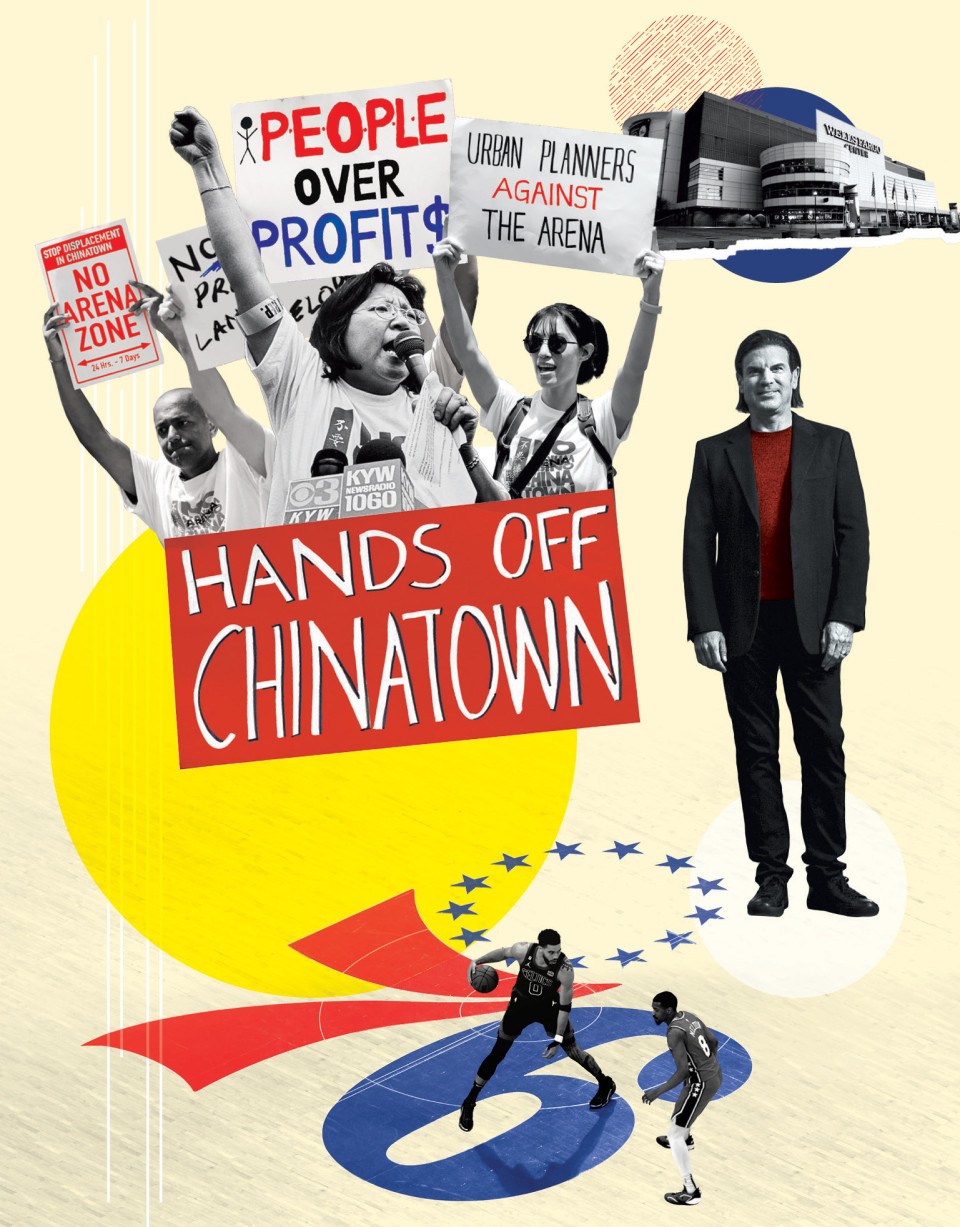

The Sixers’ arena project battle continues. / Illustration by Leticia R. Albano (Photography: Protesters: Robert K. Chin/Alamy Stock Photo; Adelman: Scott Lewis; Sixers: Stephen Nadler/PxImages/Icon Sportswire/Getty Images; Arena: Mitchell Leff/Getty Images)

“Holy shit, this is what I’m building.”

David Adelman and I are walking around outside TD Garden before the May 9th Sixers-Celtics playoff game. The Garden was built around the same time as the Sixers’ current home, the Wells Fargo Center, but feels a world away from the South Philly sports complex.

In downtown Boston, vehicle traffic continues as if nothing out of the ordinary — much less a playoff game — is happening. Underground, a sea of green-clad Celts fans flows into the arena directly from the North Station T stop. The arena is set back from the street, elevated and lit up, while the street level houses a food hall, a live-music club, a fan shop, a bar with a Topgolf simulator, and a subterranean grocery store. It’s a whole thing.

This is what Adelman, a co-owner of the 76ers, imagines when he envisions the arena he’s proposed at Market East. The $1.3 billion 76 Place would, if a lot of things go his and the Sixers’ way, open in 2031, when the team’s lease at Wells Fargo expires.

It would sit atop SEPTA’s Jefferson Station, which brings in subway, Regional Rail and PATCO lines. (It’s reachable directly from 220 stops in all.) It would replace one-third of the struggling Fashion District mall with what Adelman describes as a vibrant entertainment hub. Fans would go directly from the station tunnel to the court. And those fans would stick around for dinner and drinks afterwards.

Rendering of 76 Place, the Sixers’ arena in Market East, courtesy of the 76ers

“Your night shouldn’t just be from the time you scan your ticket to the time you leave,” Adelman says, explaining his vision of a street-level complex similar to the Hub on Causeway that flanks TD Garden. Even on non-game nights, he projects, those businesses will bring activity. Contrast this vision, the platonic ideal of a downtown sports arena project, with his description of that present-day strip of Market East: a “vastness of darkness.”

In Adelman’s view, the arena isn’t just a solution to the question of “Where will my basketball team play?” It’s a salve for a sense of uneasy emptiness that has taken over certain parts of town since the pandemic drained office buildings.

“The antidote to crime is feet on the street,” he says. A recent Brookings Institution report noted that “Center City is remarkably safe compared to the rest of the city as a whole” and that across four major cities, including Philadelphia, the amount of crime in their downtowns compared to that elsewhere was almost negligible. But it’s hard to deny that Market East can seem desolate after the sun sets. Building a shiny new arena in place of a “dying mall,” Adelman says, is a win-win. The Sixers say the arena project will use no public funds from the city and stands to increase jobs, revenue and public safety. Macerich Co., the retail developer that took majority ownership of the Fashion District after paying down $100 million of PREIT’s debt at the end of 2020, is on board with the project, too, and is already calling Fashion District the 76ers’ “future home” in its online leasing information.

But the arena is far from a fait accompli. From the moment the project was formally proposed last July, opposition from the neighboring Chinatown community has been fierce. A large protest in June showed growing resistance to the project on the grounds that it would further threaten a community that’s been hemmed in by one big development project after another. And comments-section griping from fans about parking continues apace.

Meanwhile, Cherelle Parker, who won the Democratic mayoral primary, did so with the support of the city’s powerful Building and Construction Trades unions. Those unions very much want to see the arena built, because it means several years of high-paying jobs.

Each day brings a new reason why the arena will or won’t work and a new voice for or against it: There won’t be enough parking. There aren’t enough events to fill two arenas. We need the jobs. We need something better than the status quo there. Local opinion pages have become an open forum on where the Sixers should or shouldn’t play their home games.

While the 76ers have floated other ideas for arenas in the past, as recently as a 2020 proposal to build one on Penn’s Landing, 76 Place has captured the city’s imagination and raised its ire like none before. One year after it was proposed, the question of where the Sixers will play in 2031 is somehow murkier than ever.

The Sixers aren’t shy about why they want to build an arena. They’d like to control their own destiny, which starts with not being tenants of the Flyers, who are owned by Comcast Spectacor, which owns the Wells Fargo Center. Team management cites two major grievances with the current home. Number one: The player facilities, including locker rooms and training and medical resources, are insufficient compared to those being built at competitors’ shiny, state-of-the-art arenas. And two: priority in scheduling.

The way the scheduling process works, says Adelman, is that after the Wells Fargo Center chooses dates for concerts and other family entertainment, the Flyers and Sixers draft the remaining dates. The situation, he says, prevents the team from setting its ideal schedule. “We haven’t been home for a Christmas in 11 years,” he says. That perceived scheduling imbalance, he argues, gives the Sixers a competitive disadvantage, since star players don’t have as much rest time built in for back-to-back games. Factors on the margin like this can add up and lead to fewer wins and fewer championships. (Actually, the 76ers played at home on Christmas Day as recently as 2019, though that was the team’s first home Christmas game in 31 years. Comcast Spectacor says it’s holding December 25th in both 2024 and 2025 open for the Sixers. It also counters that schedules are set by the NBA and the NHL, not the buildings housing the teams.) Dan Hilferty, the longtime president and CEO of Independence Blue Cross who in February was announced as chairman and CEO of Comcast Spectacor, which owns the Wells Fargo Center and the Flyers, says the the question about scheduling is indeed nuanced: “The truth of the matter is: There is a balanced back-and-forth scheduling process that we each go through every year.”

Rendering of 76 Place, the Sixers’ arena in Market East, courtesy of the 76ers

As for those player facilities? The 76ers just put $10 million of their own money into their locker rooms at Wells Fargo but claim there simply isn’t enough space or resources to do what’s required. “We have to go back to [the team’s training complex in] Camden for proper medical treatment,” says Adelman. Hilferty pushes back a bit here, claiming that Comcast Spectacor offered to pay half the Sixers’ renovation costs. And the 76ers push back on that. According to a spokesperson, the team was presented with multiple proposals. In one, the team would have split costs, but for renovations to spaces beyond those used by the 76ers, which is why they moved forward with their renovations.

To the Sixers, at least part of the opposition to the arena stems from a sort of close-mindedness from the public. After all, they say, 18 of the top 20 U.S. markets have downtown arenas, a trend that has picked up in the past decade with venues like the Chase Center in San Francisco and Fiserv Forum in Milwaukee. As for the eternal question of “But where will I park?,” the Sixers hope the new location being served by all those transit lines will encourage more fans to use public transportation — another win-win, this time for the environment. They plan to sweeten the deal with free train passes for season-ticket holders. And for those who continue to drive, the Sixers are planning to sell pre-paid parking passes to 29 surrounding lots that they’ll integrate with the game-ticket app. Dedicated rideshare pickup is also built into the design of 76 Place.

Proximity to the Convention Center has potential, too. Adelman is in talks with its management to team up for larger events, which would fill some of the nights when the Sixers aren’t playing and make Philly more desirable for larger conventions without the hassle of crosstown travel — as was required for the 2016 DNC, which took place at both the Wells Fargo Center and the Convention Center.

Comcast Spectacor sees things quite a bit differently. A rep there estimates that more than 80 percent of its guests drive to games (and park in one of the complex’s 22,000 spots) and more than 75 percent live outside the city. Habits aren’t so easily changed. The Boston metro area, management explains, has historically been more dependent on public transit than has Philadelphia, making TD Garden, in their view, a disingenuous analogy.

And then there’s the matter of events, which, some suggest, there simply aren’t enough of to support two arenas. Between the Sixers, the Flyers and concerts, WFC has a pretty full schedule and, at least according to its reps, has to turn away very few concert requests because of scheduling conflicts.

And luring any of those concerts from Wells Fargo could be a challenge for a downtown arena. Wells Fargo has a huge loading dock and lots of bus and truck parking, and it’s literally right off the highway. When Bruce Springsteen’s tour was recently delayed due to a band member’s illness, a rep tells me, the trucks had room to park in the Sports Complex lot for days to wait it out.

The Sixers’ current home in the Wells Fargo Center / Rendering courtesy of Comcast Spectacor

The venue’s decades-long relationships with companies like Live Nation and AEG aren’t a negligible hurdle, either. Veteran concert promoter Larry Magid — he’s been in the biz for more than six decades, having co-founded the Electric Factory and served as chairman for Live Nation Philadelphia — remains skeptical. “The question I ask is, ‘How many dates do you come up with to make an arena successful, and who are the players?’ A company like Comcast, who’s been so great for Philadelphia and so well-funded … personally, I’d never bet against a company like that.”

The Wells Fargo Center currently hosts about 220 events a year, the core of which are Flyers and 76ers home games. (It also hosts Wings lacrosse, Villanova basketball, concerts, and family shows like Disney on Ice.) To reach even the 150 event nights the 76ers cite in their projections, “You’ll have to take away a lot of events from the competing arena,” Magid says — and he doesn’t foresee Comcast Spectacor backing down.

Also among the doubters: Sam Katz, the erstwhile mayoral candidate who spent a big chunk of his career financing major projects, including numerous stadia and arenas. He doesn’t think the demand to support two major indoor arenas exists. In an October 2022 op-ed for the Inquirer, he characterized the Sixers’ claim that they can fill those nights as “a pipe dream, totally disconnected from both experience and reality.” (Since writing that op-ed, Katz has, as of June, joined an internal planning group convened by Hilferty to rethink the future of the South Philly sports complex of which the Wells Fargo Center is a part.) He says that growing demand for larger stadium shows (think Taylor Swift at the Linc) and smaller, intimate shows (think Elvis Costello at the Met) makes midsize arena shows a shrinking market.

Meanwhile, the Wells Fargo Center is in the final stages of a $400 million renovation begun in 2016. (A rep for Comcast Spectacor describes it as a “transformation,” noting that “everything but the steel and concrete” is being redone, including wiring and plumbing, and that there are plenty of fancy fan-facing upgrades.) This summer’s project? The very facilities at issue between the Sixers and their landlords. Comcast Spectacor projects the locker rooms will be done by fall, in time for the 2023-’24 NBA season’s October start. It’s also adding and expanding new medical and training facilities.

Adrian, the new Stephen Starr restaurant at Wells Fargo Center, was part of their ongoing renovations. / Photograph courtesy of Comcast Spectacor

For its part, Comcast Spectacor would love for the Sixers to not only stay, but to buy into the Wells Fargo Center and have part ownership.

“We would want nothing more than to build a partnership,” Hilferty says. “We would welcome an opportunity to create a 50-50 ownership [with the Sixers].” He explains that Comcast Spectacor would continue to manage the Wells Fargo Center, but the partnership would lay a foundation for the next chapter, too. They may have extended the Wells Fargo Center’s lifespan with the renovations, “but at the end of the lifespan, let’s build the next world-class arena, and let’s focus on looking at development opportunities right here on our existing property.”

The big vision is one of a more vibrant stadium district: collaboration between the four major teams who call it home to welcome more restaurants, housing, a hotel, and entertainment venues — they’ve even thought about building a stadium-district music venue to capture some of that smaller-show market. Hilferty sees this future as brighter if the Sixers remain part of it.

And if you tilt your head just right, there’s a way of looking at this whole arena proposal as posturing by the Sixers to gain leverage in such a deal. It wouldn’t be the first time a team has threatened to move to win a more favorable bargaining position.

None of these concerns matter if 76 Place isn’t approved by the city. And politicians seem to be viewing the project as an opportunity perched over a perilous third rail.

With Cherelle Parker’s primary win in May, we now have a presumptive mayor who has spoken positively of the arena project and who received a lot of backing from the building trades. When 76 Place was announced in July 2022, Parker tweeted that she was “excited by the opportunities.” And while she took a more measured stance on the campaign trail, stressing the importance of neighborhood input, she criticized “reflexive opposition” to a project that has the potential to create thousands of jobs. Specifically, it could mean nearly 10,000 union construction jobs, according to the leader of the Philadelphia Building Trades, Ryan Boyer, whose endorsement of Parker has been characterized as decisive in the crowded primary race. In a March op-ed supporting 76 Place in the Philadelphia Tribune, Boyer declared, “The economic benefits are truly limitless.”

But while a mayor certainly has a great deal of influence, it won’t technically be up to her.

The plans for 76 Place take up the 1000 block of Market Street now occupied by part of the Fashion District mall. That property is currently zoned CMX-5, meaning it’s approved for mixed-use development in Center City. An arena is considered “special use,” which under Philly’s zoning laws requires a variance from City Council. The arena would also extend north, requiring the “striking,” or removal, of Filbert Street between 10th and 11th from the city grid to connect the facility to the former Greyhound station, which is also part of the plan. That means even more legislation.

Enter City Councilmember Mark Squilla. He represents the 1st District, which includes Chinatown and Market East, so he has what’s called “councilmanic prerogative” to bring the land-use legislation before the Council.

If it does pass out of committee, it will go to a public hearing — sure to be contentious — and then finally to a full Council vote. This fall, there will only be 15 Councilmembers, since Helen Gym and David Oh resigned to run for mayor and have yet to be replaced. But the legislation still requires nine affirmative votes — essentially a super-majority, which may be difficult to achieve given the controversy.

“There are a few Councilpeople who have come out and told us they will not support the arena,” says Debbie Wei, co-founder of Asian Americans United, which has previously organized against Chinatown development. Wei says she thinks Squilla “doesn’t want to be the bad guy. He doesn’t want to carry the weight of this.”

Anti-arena protest in Chinatown this past June / Photograph by Joe Piette

Squilla is noncommittal when talking to me about the arena, especially after a bill he introduced in December about unrelated parking-garage refinancing included a provision that would have made it easier to axe the stretch of Filbert Street included in the 76 Place plans. The language appeared mysteriously, and Squilla claimed to have no knowledge of the last-minute addition. He said at the time that it was added by an attorney at Klehr Harrison who Squilla believed was submitting the Kenney administration’s final version, but the Kenney administration said it didn’t direct the attorney — who is in fact working with the Sixers development team — to add the language. In addition to raising the question of how, exactly, our legislation gets written, the flap sowed further mistrust among Chinatown community members who already felt blindsided and left out of the process.

Since then, Mayor Kenney has commissioned the Philadelphia Industrial Development Corporation to conduct impact studies, including on the community, financials, parking and traffic. Squilla tells me he’s waiting to see the results of those studies — and that he plans to make them available to the public for 30 days before he decides whether to bring legislation at all. “We know there’s still going to be opposition even after the studies are done,” he says, “but at least we’re going through and getting the information necessary to share with the stakeholders so they can then make an educated decision.”

Meanwhile, the Sixers’ legal team has been working on proposed language for the ordinance. It would be a “collaborative effort” between the city’s law department and 76 Devcorp, Squilla explains. And while the Sixers were originally hoping for approvals by June, it’s now looking like this legislative process will begin in the fall, “at the earliest,” he says.

Chinatown sees 76 Place as just the latest threat to its tenuous existence. While economic and political issues may ultimately decide the outcome, the conflict with Chinatown seems to take up the most oxygen.

The Sixers’ best play on this front appears to be winning favor through a community benefits agreement — a contract negotiated with the surrounding neighborhood. The Sixers have promised such an agreement, and politicians say they won’t consider the project without one. Team management has said it plans to invest $50 million in public safety, affordable housing and small businesses in the neighborhood. The CBA would be legally binding for 30 years.

Chinatown remains unconvinced by the Sixers’ overtures. The Philadelphia Chinatown Development Corporation came out against the arena in March. The project started off on shaky ground, with Chinatown advocacy groups like Asian Americans United claiming they had no notice of the plan prior to the July 2022 announcement. “At this point, it’s impossible for us to trust them,” says Wei. Since then, Adelman and the Sixers have met with the group, but Wei says members didn’t feel their questions were answered. This summer, the Sixers met with other neighborhood groups like the Washington Square West Civic Association, and they have reengaged with Chinatown.

And while the city is conducting its own impact study, the results are unlikely to assuage arena opponents in Chinatown, who felt parameters laid out in the study’s request for proposal lacked specifics and had an impossibly quick turnaround. Wei says Asian Americans United submitted its own draft RFP to the city, but in the final version, much of the community-focused language had been taken out. (Since then, it has been announced that the Sixers would fund these impact studies. The news was met with skepticism from neighborhood groups opposed to the arena, citing concerns that the Sixers’ financing will create undue influence. The city has explained that they asked 76 Devcorp to foot the bill because it didn’t seem right to use public funds to do so, but that the study would remain entirely independent.)

While the proposed arena site isn’t in Chinatown proper, its proximity means the neighborhood will bear a heavy burden. The projected six years of construction would make access to Chinatown difficult. “I know my coffee shop couldn’t survive six years of bulldozers, cranes, wrecking balls, and traffic blocking customers, workers and deliveries,” Will Gross, an organizer with Restaurant Industry and Small Businesses for Chinatown’s Existence (RICE), declared at a massive anti-arena protest in June.

Anti-arena protest in Chinatown this past June / Photograph by Joe Piette

There are concerns that small businesses and residents would be priced out of the neighborhood they’ve spent decades preserving. “When the small businesses close, the things that are sustaining families close,” says Wei.

Adelman pushes back on that idea. “The Phillies ballpark [the downtown venue proposed in 2000] would have displaced people; it would have been eminent domain,” he says. “The Convention Center displaced people and businesses. The Vine Street Expressway did that. This isn’t that — we’re not going to displace one business or one resident.”

Responds Wei: “We’re not stupid.” She sees this as a clear “land grab” by experienced developers.

Back in Boston, before the 7:30 p.m. playoff game, I walked around near the arena and wandered into Halftime Pizza a block away from TD Garden. Matthew Pasquale, along with his brother, runs the business opened by their grandfather 45 years ago. I asked him how the area had changed since the arena came in. “We love the crowds, the fans. They keep us going and we keep them going,” he told me. The crowds can get rowdy, he admitted, mentioning a fight that once broke out in the restaurant, but overall, he’s grateful to be situated near the arena: “When a game lets out, it’s like a rush of people in here. … Businesses will not be disappointed with the foot traffic it brings in.”

But according to Wei, not all foot traffic is created equal. She recalls a similar — to her, unfulfilled — promise that the Convention Center would be great for business. “You might get an occasional person, but they don’t give you the business that regulars give you,” she says. “And if the regulars can’t come in, they stop coming.”

Of course, season-ticket holders have more potential to become “regulars” than folks in town for a one-off business conference, but the point stands: A development like this may promise customers, but they’re likely to be a different kind of customer.

Deep down, the question of economic benefits may be beside the point. And the overwhelming cast of stakeholders makes it very likely that at least one group will be disappointed with the eventual outcome. To opponents of the arena, this is a battle for the soul of their neighborhood, one that has been home to an immigrant population that settled there 150 years ago, when it was an undesirable location, and built a community. Not for nothing, they point out, in the then-desolate space that might have housed a Phillies stadium now live the Asian Arts Initiative, the Folk Arts-Cultural Treasures Charter School, and the Crane building — created since by the community, for the community. The parties may never see eye-to-eye — because they were never playing the same game.

This story has been updated to better explain the scheduling process for the Wells Fargo Center, to add a response from the Sixers about a renovation proposal from Comcast Spectacor, and to add context about when the Sixers have played on Christmas.

Published as “Clash of the Titans” in the August 2023 issue of Philadelphia magazine.