LaFaye Gaskins, Whose Conviction Was the Subject of a Philly Mag Investigation, Freed From Prison

Gaskins is free 34 years after being arrested and convicted for a murder there was no evidence he had committed. “It makes me feel like I'm a tourist coming to a city that I don't know,” he says.

LaFaye Gaskins out to dinner (left) and with his mother, Myra Gaskins, and reporter Dan Denvir in June 2023. | Photographs via Daniel Denvir

I visited Philly last week to spend time with LaFaye Gaskins, whose murder conviction I investigated for this magazine in 2016. Gaskins, 54, walked out of prison on the morning of Friday, June 9th, after spending 34 years behind bars on a life sentence for a murder there was no evidence he had committed.

“It makes me feel like I’m a tourist coming to a city that I don’t know,” he told me. “And I’m just walking around trying to figure everything out. That’s how I feel. Even when I went to my old neighborhood, it’s totally different.”

The Raymond Rosen high-rise projects where he grew up have long since been demolished. People’s clothes, he notes, are far tighter these days. Everyone is staring at cell phones, which he’s learning to use for the first time. He’s struggling not to speak too loudly in ordinary conversation after three and a half decades of having to make himself heard in a noisy prison. He’s enjoying sleeping on a real mattress. “It’s amazing, but I still sleep like I’m in prison, ’cause I still only sleep on one side,” he says, laughing. “I haven’t got a chance to like roll over like that, because I still have the mind-set that I might fall out the bed.”

I first met Gaskins in June 2014, when I made the two-hour drive from Philly to SCI-Mahanoy in Schuylkill County. I spent the following two years investigating the 1989 murder of Albert Dodson, who, like Gaskins, had made a living selling drugs. I discovered there was absolutely no hard evidence that Gaskins had killed him: The record made it clear that Gloria Pittman, the eyewitness whose testimony sealed Gaskins’s conviction, was pushed to make an identification after repeatedly saying — to police and in open court — that she hadn’t seen the apparent shooter’s face.

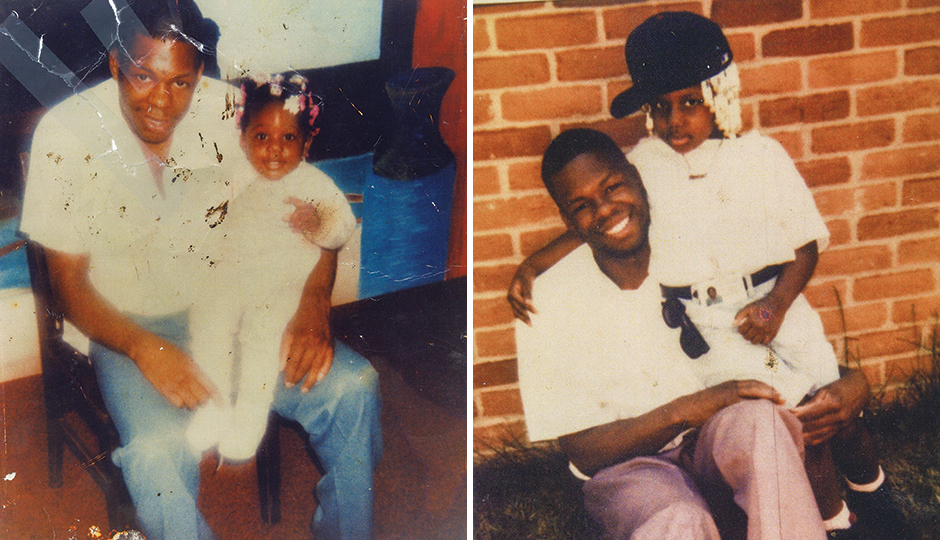

Two shots of LaFaye Gaskins with his daughter, Onia Gaskins, from Philly Mag’s 2016 story. | Photographs courtesy of LaFaye Gaskins

I wasn’t the first person to reinvestigate Gaskins’s case. Gaskins was. I was a reporter at the Philadelphia City Paper, and he sent me a letter informing me that Pittman was recanting her identification. I’d received many letters from prisoners over the years, asking for me to look at their cases. There were only three of us on City Paper’s news team, however, and I had to publish something in the paper almost every week. I simply didn’t have time to spend a year or two reinvestigating a two-decade-old murder if it wasn’t going to lead to an article for the paper. But Gaskins gave me something concrete and critical to go and check out. So I did.

I knocked on Pittman’s door, and she told me the same thing she’d told the police and, later, a judge, more than two decades earlier: She hadn’t seen the man’s face but was pushed to say she had. My next stop was the Philadelphia Court of Common Pleas clerk’s office, to retrieve Gaskins’s case file. It was, inexplicably, missing. Fortunately, Gaskins’s mother, Myra, had a copy and lent it to me. If she hadn’t had a copy, Gaskins would still be in prison today.

The case file confirmed what Pittman’s recantation had suggested: There was absolutely nothing like solid evidence that LaFaye Gaskins had murdered Albert Dodson. The evidence not only failed to approach anything close to “beyond a reasonable doubt”; the police and trial record contained a narrative that was bizarre and didn’t make any sense. In fact, what evidence existed prompted all sorts of questions that seemingly went unasked and introduced more plausible suspects who apparently were never pursued.

Once police identified Gaskins as a suspect, the record suggests, they stopped looking at anyone else. And they clearly pressured two separate witnesses to alter their radically different accounts to match one another. Gaskins fit the general description: a young Black drug dealer, and one police apparently believed (almost certainly erroneously) was a member of the infamous gang Junior Black Mafia. That there was no specific evidence Gaskins had murdered Dodson was immaterial. All of the details were inconvenient for the prosecution, but it didn’t matter.

“I’m going to jail for the rest of my life because of what somebody thought that they seen,” Gaskins said to the judge. “It wasn’t no facts or nothing going on in the case. Nobody seen me actually kill nobody. I didn’t kill nobody.”

Gaskins’s legal problem was that there was no rock-solid evidence he was innocent, either. This is a major issue with run-of-the-mill wrongful convictions: Many people like Gaskins, ironically, are convicted on flimsy and contrived evidence; if there’s just a bad eyewitness identification, there’s little they can do to prove their innocence and overturn their convictions. If there’s no physical evidence, there’s nothing, for example, that can later be subjected to DNA testing that might definitively prove their innocence. The lack of evidence of your guilt often means there’s no possible evidence of your innocence.

After my story was published in Philadelphia (the City Paper, a victim of the alt-weekly apocalypse, had closed), the Pennsylvania Innocence Project picked up the case — and that turned out to be the game-changer. Gaskins’s attorney, Nilam Sanghvi, was relentless. But the process was painfully slow. Ultimately, the Philadelphia district attorney, confronted with the conviction’s injustice, and with the fact that the Philadelphia courtroom had failed to transcribe a key April 2022 hearing, allowed Gaskins in March to plead guilty to lesser charges — third-degree murder, robbery, and possessing instruments of crime — that would allow him to walk free. Again, he maintains that he didn’t have anything to do with the murder of Albert Dodson, and the evidence strongly suggests he’s telling the truth. But this was his ticket to freedom, and he took it.

From left, Onia Gaskins in her Navy uniform; LaFaye with his mother, Myra Gaskins, from Philly Mag’s 2016 story. | Photographs courtesy of LaFaye Gaskins

Over the years, I’ve spoken to Gaskins every few weeks, and emailed with him, too, through the controlled prison email system. We talked about the news, about how Donald Trump was such a clown. How the election of Larry Krasner as DA might finally bring some measure of justice to the justice system. About how young guys coming into his prison seemed lost and frequently beset by mental illness.

Gaskins was excited to come home. But he was nervous, too. A lot of people don’t have an easy time readjusting once they come home after such a long stretch inside. Gaskins, however, has a lot going for him. Sitting down on a Saturday in early June for his first restaurant dinner since George H.W. Bush was president, he told me it took him seven years behind bars to let go of his anger and resentment. He recognized that hanging onto the past would doom him, consuming whatever future he might have. He continues to believe that today.

LaFaye Gaskins deserved to be fully exonerated and to have the City of Philadelphia financially compensate him for the three and a half decades of his life stolen from him. But without evidence of actual innocence, simple freedom is perhaps the closest thing to justice that most wrongfully convicted people — the people churned through our criminal-legal system’s assembly line of arrest, prosecution, and imprisonment — can hope for. For now.

“My real realization that I was home was three days ago,” he told me last Friday, “when I woke up in the morning and realized I was home, and I started crying. And I went in the room and told my mother I love her.”

Daniel Denvir is the host of The Dig podcast and a co-chair of Reclaim Rhode Island.