Meet the Man Who Brought the Boulevard Subway Back From the Dead

Jay Arzu learned about Philly’s most notorious unbuilt subway when he was looking into its New York sibling. Now, as a city-planning doctoral student at Penn, he has put the project back on the map.

Jay Arzu, speaking at the August 2022 town hall on the Roosevelt Boulevard Subway / Photograph courtesy Jay Arzu

Back in 2015, after the Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission took the Roosevelt Boulevard Subway off its list of should-do transportation projects, I wrote that, despite that move, the Boulevard subway was Not Dead Yet.

Here it is, seven years later, and sure enough, it’s risen from the grave.

State Rep. Jared Solomon, a Democrat whose district stretches from Tacony to Oxford Circle to Castor Gardens in the central Northeast, has been stumping for it in a series of town halls. The Chinese immigrants who have transformed Mayfair have voiced their support. And even though it still isn’t on the DVRPC’s wish list, it has made it back onto PennDOT’s radar screen: Last month, the agency pledged to conduct a study to determine the feasibility of a Boulevard subway.

And we have a New York transplant to thank for its resurrection.

Jay Arzu, a doctoral city planning student at Penn’s Weitzman School of Design, took an interest in the dormant subway project even before coming here to study. He, too, saw the parallels between the Boulevard subway and New York’s long-sought, partly-open Second Avenue Subway, and he figured: If New York can finally complete at least a piece of a subway line it long desired, why can’t Philadelphia?

And so, once here, he got to work, campaigning for it both in person and (since July) via his Twitter account @BlvdSubway. Recognizing a fellow urbanist and train geek, I figured I’d ask him why he chose to fight this particular good fight.

So you were born in the Bronx. Have you always been interested in subways?

Yes. I grew up in public housing. And one of the best things about my neighborhood was that we had access to two subway stations on 138th Street. And because of that, it gave us access and opportunity to go to Manhattan, see Broadway shows, access to jobs. As a teenager, I worked at a theater in lower Manhattan, and I knew that I couldn’t do that without the subways.

And the subways were dear to my heart because I was always an adventurer. I wanted to see the different stops and ride every line.

I can say that I was a major New York City subway fan, and learning about the lines that weren’t built was just as interesting. So, learning about the Second Avenue subway, and watching as the city started work on Phase One, I was excited about it. And that’s around the time that I learned about the Roosevelt Boulevard subway for the first time.

[Work on Phase One of New York’s Second Avenue line began in 2007, and the three-station segment opened a decade later.]

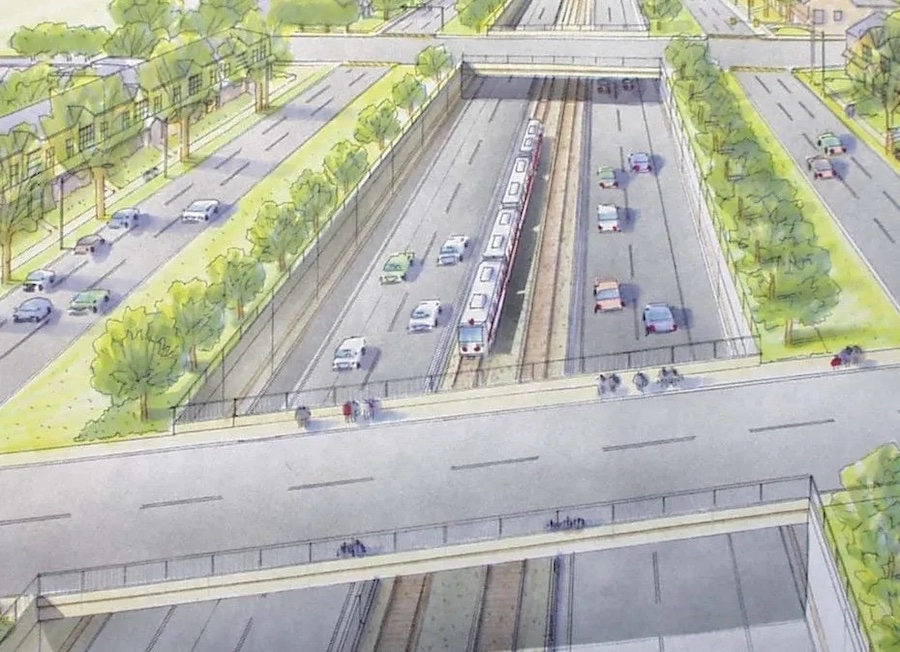

This illustration from a 1940s city study depicts a Roosevelt Boulevard freeway with a rapid transit line in its median / Renderings: Philadelphia City Planning Commission via Streetsblog USA

So how and what did you learn about the Boulevard line?

So in researching the Second Avenue line and the different transit authorities, I came across SEPTA. At first, I was researching SEPTA’s recently abandoned trolley lines — in the ’80s, they had abandoned a bunch of trolley lines, and I thought that was one of the biggest transportation blunders ever.

Through researching that, I came across the Boulevard subway, and I was astounded to hear about something that would connect a section of the city that’s semi-disconnected from the [rest of the] city. I thought it was an amazing project, and I was curious to find out why it hadn’t been built.

I was able to find Philadelphia’s comprehensive master plan from 1960. And they had full plans to build the Roosevelt Boulevard subway then, but in the median of a Northeast freeway that would have been built with it, pretty much destroying Roosevelt Boulevard.

And I was like, “Let me continue and see what else is available.” And I looked at the other studies on Roosevelt Boulevard and there were plenty — there’s too many, honestly. But if a city is willing to study a corridor over and over and over, there has to be something there.

Is that why you decided to study at Penn?

What’s interesting is that I had studied SEPTA and the city of Philadelphia for years and had only been there once or twice, to see my aunt. And Penn was a campus that I thought I could be comfortable at. And I told them straight up, “Hey, I want to be a doctoral student, but I also want to work in the community. It’s important to me as a human being to be able to give back.” And they were 100 percent behind me, and that’s one of the reasons why I came to Penn.

Were you able to get your hands on any of those other studies?

The one that I wanted to see the most was the 1999-2003 study [the most recent study conducted by the city, which, like those before it, also called for building the subway], and I could not find it for years.

Then, last year, I happened to be in a class with SEPTA’s general manager, Leslie Richards. She’s an amazing technocrat, bureaucrat, whatever you want to call her. And she’s an amazing professor as well. She was always willing to listen to our thoughts. So I asked her, “Would it be possible, if you could, to give me this 1999-2003 study?” And that’s how all this began.

I knew from the moment I read it that this has to be built. It would potentially save lives. And it would give people access to opportunities they don’t have today.

And it lit a fire inside me — a belief that if there’s a will, if the community wants this, if they believe that the Roosevelt Boulevard subway could benefit the community, then we should push for it.

This rendering from the City Planning Commission’s 2003 study of the Boulevard depicts the same thing; Arzu opposes the freeway. The first version of PennDOT’s “Route for Change” study estimated a capped freeway would cost $10 billion; Arzu and other subway advocates argue the subway would cost less

This reminds me of one of my favorite quotes. It comes from a community activist in Boston named Mel King, who came close to becoming the city’s first Black mayor in 1981. He was known to say, “Ask for what you want, not what you’re told you can get.”

Exactly. And when I spoke to people about [the Boulevard subway], they were like, “Jay, this is not possible. We shouldn’t be asking for this. We should just stay focused on trolley modernization and ‘Reimagining Regional Rail’ [SEPTA’s plan to improve Regional Rail service].”

Don’t get me wrong. Regional Rail is important. But we should be ambitious. We should be thinking about a bright future for the city of Philadelphia, not one where we’re just coasting. I want Philadelphia to be a great city.

So I read the study, and I knew I had to do something, and I thought, “You know what? I’ll write an op-ed for The Philadelphia Inquirer. Maybe a few people will read it; maybe a few policymakers will do something.” So I wrote the op-ed, and I felt like I didn’t get the buzz that I wanted. And that’s when I started to take things further and personally reach out and call offices to talk to them about the op-ed, including Councilmember Kenyatta Johnson’s office. They challenged me and told me, “Do Northeast policymakers agree with this?” And I said, “Hey, I’m speaking to everybody,” and I doubled my efforts.

And is this how you wound up talking to Rep. Solomon?

Jared Solomon actually reached out to me. People said that for years, he has wanted to see some form of change on the Boulevard. And when he reached out, by this time, I had released a second op-ed about the subway, and he was like, “I think we should have a discussion about this. I think we should have a town hall where we can actually gauge the community’s feelings about the subway.”

Truthfully, I was a little nervous about it, going into a Northeast Philadelphia community that was not my own. [But] it was so warm, it was so cordial. This was in August 2022. We didn’t know how many people would show up, but people kept coming, and they kept coming, and it was standing-room-only in a few minutes.

Then, when people started speaking, I expected it to be a mixed bag — some people who would support the subway, some people who would support light rail, and some people who would say, “I don’t want anything coming up the Boulevard.” And the community members started speaking, and they wanted the subway, and I was like, “Whoa.” I came into this with good intentions, but the community really wanted this. They were like, “We feel disconnected. We don’t have access to as many jobs and opportunities as the rest of the city. We want that to change.”

Of course, there was one person who brought up crime, but the majority of the room, including the Chinese American merchants, was like, “This is an opportunity to improve our neighborhood, to improve this section of the city.” People were talking about the Roosevelt Boulevard subway for the first time in 20 years, and they had an interest in seeing if this was a possibility.

[Afterwards] Solomon was like, “Let’s do a follow-on.” At the first one, we were supposed to have people from DVRPC, but they bailed at the last minute. And some people at the first meeting were visibly upset that people from SEPTA, DVRPC and OTIS [the Mayor’s Office of Transportation, Infrastructure and Sustainability] weren’t there. [Actually, Christopher Puchalsky, policy director at OTIS, did attend the first town hall.]

So at this second meeting, we had [representatives from SEPTA and OTIS] and Ashwin Patel [civil engineer manager for District 6 at PennDOT]. Our hope for the meeting was that we could get SEPTA and PennDOT and OTIS to say, “Okay, there’s actually a community want here, and we want to apply for a planning grant so we can study a heavy rail alternative.”

And what really changed everything was when Ashwin Patel said, “There’s no need; we’re going to have a heavy rail alternative in the second iteration of Route for Change” [the PennDOT-sponsored study of Roosevelt Boulevard’s future; the first version, released in the summer of 2021, did not include a subway among the long-range options for the Boulevard].

So the subway is, in a sense, alive. It’s not a dead idea anymore. And with us putting our hand out and asking for a subway that could revolutionize how people move around Northeast Philadelphia, and connect it to the region and the economic opportunities that will come along with it, it’s a game-changer. And I know it would score well in the FTA [Federal Transit Administration] New Starts program. We just have to get it on there.

Updated Dec. 29th, 1:15 p.m., to clarify the nature of the conversation Arzu had with Councilman Kenyatta Johnson’s office, which provided Philly Mag with a copy of the e-mail messages.