What a German Taught Me About His Country and the Holocaust

In Germany, children learn about the darkest chapter in the country’s history at a young age.

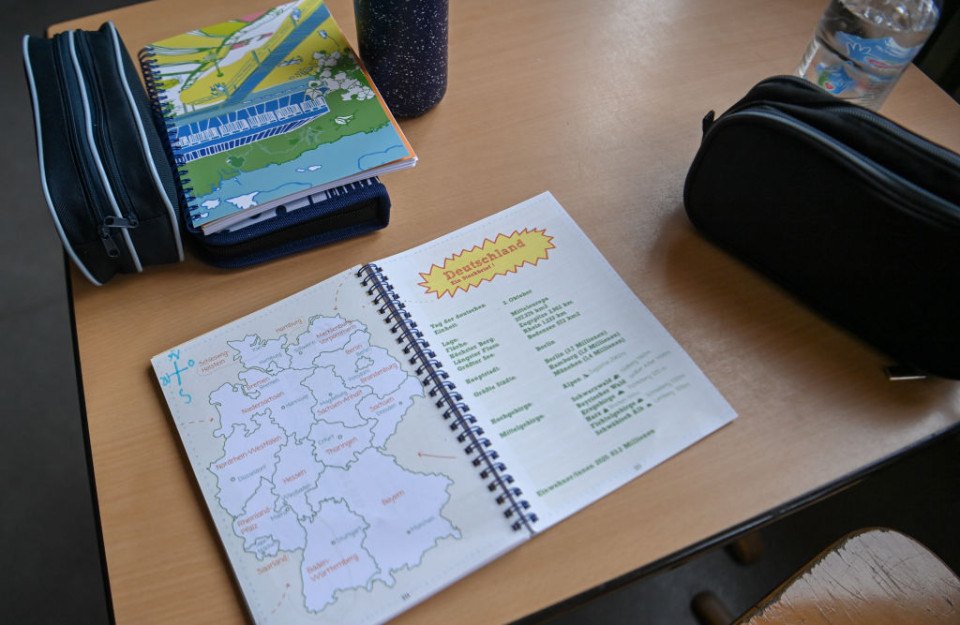

A school desk at the school in Köllnische Heide in Neukölln, Berlin / Photograph by Jens Kalaene/picture alliance via Getty Images

Back when I was in college, a good friend started dating a German guy. He was from a small town in Bavaria and owned lederhosen and everything. After hearing about him, I was really keen to meet him and found out, to my complete surprise, that he didn’t feel the same way. He was terrified to meet me. You see, I would be one of the first Jewish people he would ever meet, and his education on what his people had done to my people in the Holocaust sat heavy on him. How would I regard him? Would our dual-sided generational trauma be a wall between us?

That all shook out quickly between me and the German, and I came to learn that in his homeland, schoolchildren are taught a visceral history of the Holocaust, beginning in elementary school and later including visits to concentration camps such as Auschwitz and Dachau (from which my maternal grandfather was liberated). In the years following the war, the Germans came to understand that to root out a hatred as endemic and ultimately as destructive as the one that gave rise to the Third Reich, they had to target the youngest hearts and minds. As traumatic as this past is to later, innocent generations, to omit or dilute the truth of it from history lessons would only allow the tentacles of anti-Semitism to stretch on.

Today, as a mother of two young children in Philadelphia schools, I’m taking in the national conversation on critical race theory and, more broadly, how we teach America’s history of slavery, racism, and Indigenous genocide in our schools. And I’ve thought a lot about “the German.” It was clear that an unflinching education on the events of the Holocaust left him with feelings of guilt and shame, but those lessons ultimately fertilized a great sense of empathy as well as an openness to discussing history that helped us both heal the decades-old wounds of our peoples’ pasts. He still donned his lederhosen and embraced his German heritage, but he also wore the dark layer of his country’s worst history as a weighty responsibility, without resentment.

I wish that today’s opponents of teaching our children the history of slavery, racism and genocide in America could meet more Germans. If their resistance truly stems from not wanting white children to feel guilt, shame, and loss of pride in who they are, I would point to the empathy I experienced so many years ago, when meeting me made a man shake in his lederhosen. I’ve since met other people educated in Germany, and they’ve all expressed how formative their Holocaust history lessons were to understanding the injustices of our own times, along with a sense of pride in modern Germany. Ultimately, we know that within the opposition lies the very disease we aim to fight, attempting with each generation to mutate and live on — because that’s what diseases do.

Anti-Semitism hasn’t been snuffed out entirely in Germany, just as racism may never be here. But approaching the past honestly is as powerful an antidote as we have. Teaching America’s children about the indelible racism that is our country’s legacy and instilling national pride in them need not be an either/or proposition. Individuals have complicated dualities, and so do nations. If a German and a Jew can come together on that, why can’t America?

Einav Keet is a Philadelphia writer and mother who has enjoyed writing about health, science, technology and politics for more than 15 years.

Published as “Pride and Prejudice” in the September 2022 issue of Philadelphia magazine.