Main Line Mystery: Dallyn Pavey’s 40-Year Search for Her Vanished Dad

Forty years ago this July 1st, a Main Line woman’s fast-living father disappeared without a trace. She’s still searching for answers.

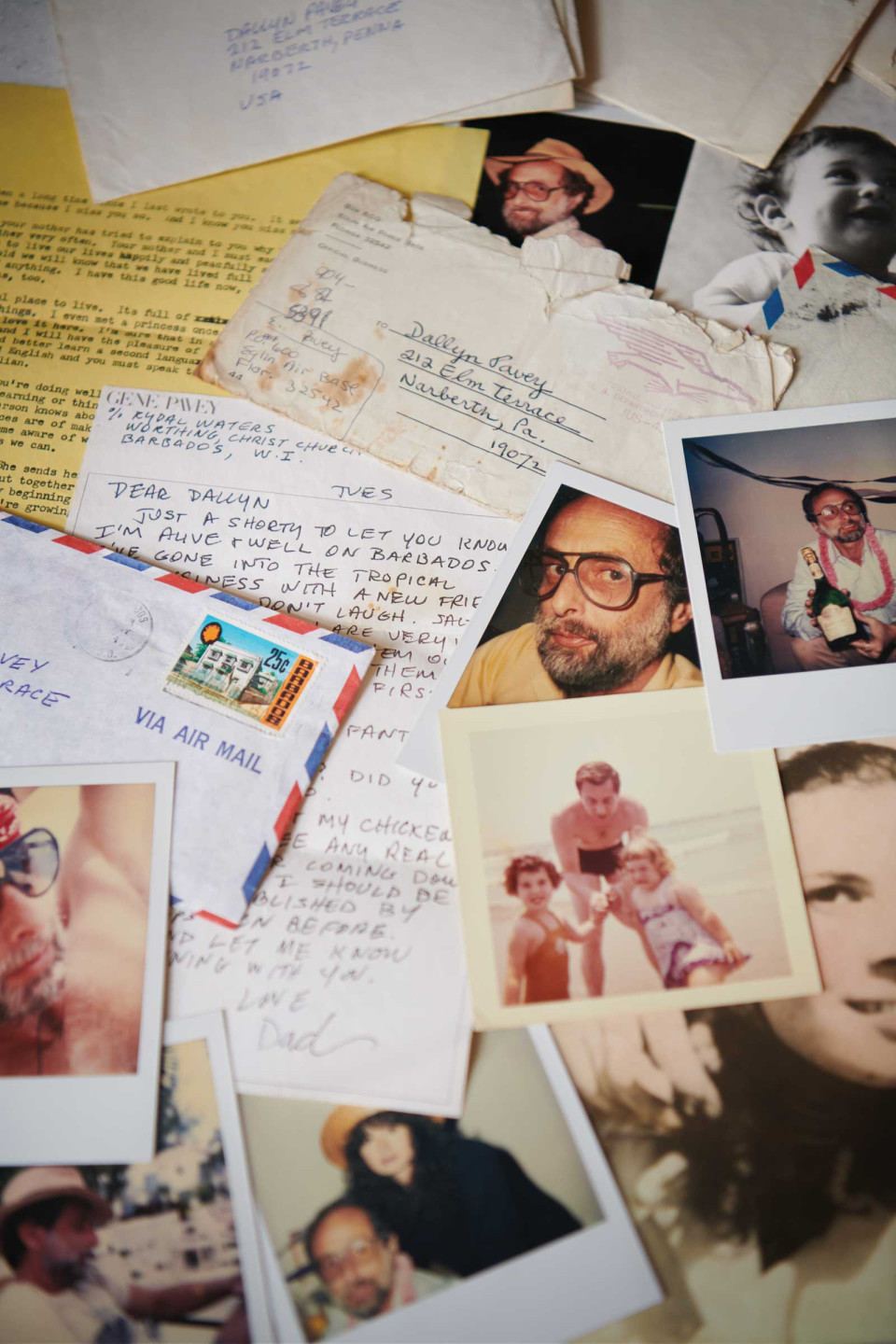

Dallyn Pavey keeps photos, letters, and clues about her missing father Gene Pavey / Photograph by Dave Moser

Dallyn Pavey’s basement in Wayne is more interesting than most.

First, there are the gold and platinum records hanging on the walls. Some were earned by her husband, David Uosikkinen, drummer for the Hooters, the Philly band you may remember for the 1980s hits “And We Danced” and “All You Zombies” — songs they played for Live Aid at JFK Stadium in July 1985.

Other commemorative records on display in the basement were awarded to Dallyn herself, back when she did PR work for bands including Cinderella, the glam metal group from Delco, and Nelson, those blond twin sons of Ricky Nelson.

Across from her framed records, on the back of a closet door, is a handwritten note from Graham Nash — as in Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young — inscribed with the lyrics for his song “Our House.” You know the one:

Our house

Is a very, very, very fine house

With two cats in the yard

Life used to be so hard

Now everything is easy ’cause of you …

Nash, who knew Dallyn through her close friend Pierre Robert at WMMR, gave her the gift on the occasion of her prior marriage, to Main Line design executive Alan Jacobson, who just so happens to be the father of Abbi Jacobson — creator and co-star of the hit Comedy Central series Broad City and lead in the long-awaited Amazon Prime TV adaptation of A League of Their Own.

On the other side of the room, near a set of glass doors that overlook a wooded expanse, is a practice area crammed with a drum set, amps and a keyboard, where fellow Hooters Eric Bazilian and Rob Hyman were expected to materialize later on the day of my visit, to rehearse for an upcoming 28-city tour of Germany. Big in Bavaria, as they say.

And then there’s the evidence of a certain someone’s Bruce Springsteen obsession. Dallyn, who has seen the Boss play live more than 100 times, might just be his number one fan. She certainly has the merch and memorabilia to stake that claim. The framed ticket to his MTV Unplugged performance. The signed setlist, complete with Bruce’s boot-print from where he stepped on it onstage. The items that get the most real estate are the framed photos and news clippings memorializing the time in 1988 when Springsteen pulled a 29-year-old Dallyn up onstage with him at the Spectrum during “Dancing In the Dark,” the way he famously did with a pre-Friends Courteney Cox in what became the MTV video for the song.

But even with all that, it’s what’s atop a white Ikea table in the middle of this collection of memories and conversation-starters that holds my interest. Dallyn calls this table her office. And this is where she keeps an overflowing dossier on Eugene “Gene” Pavey, her father.

There are photos. There are letters from half a century ago, some written from prison. There are all sorts of slips of paper, postcards, and other aging documents that paint a picture of who this man was, the story of his life told in bursts, snippets, and one marked-up résumé. It’s a story that ends abruptly on July 1, 1982, the day 40 years ago that 50-year-old Gene and his new teenage bride, Melanie Mass, left Fort Lauderdale in his cigarette boat, never to be seen or heard from again.

Dallyn suspects her dad fell victim to the Miami branch of the murderous Medellín cartel. Then again, his expected course for the trip had him passing right through the mysterious Bermuda Triangle. Or did he escape the life of fast boats and powdery kilos and live out the rest of his days in a place built for those who don’t want to be found, like, say, Argentina? Theories abound.

“He’d be 90 today,” says Dallyn. “I just want to know what happened.”

July 1, 1982, wasn’t the first time Gene disappeared from Dallyn’s life.

Dallyn’s mom, Roz, a native of Northern Liberties, moved to New York City in the mid-’50s to pursue a career as a dancer after dabbling in a tap-and-ballet act in Northeast Philly and Atlantic City. A girlfriend introduced Roz, a stunning brunette, to Warren Beatty before he was Warren Beatty, but Roz thought the aspiring big-city actor was just too attractive to be serious relationship material. Instead, she fell for the more acceptably average Gene, a native New Yorker who lived in her building on West 83rd.

After graduating with a BA from Brooklyn College in 1955, Gene worked on a publicity campaign for Chesterfield cigarettes, pushing smokes on college students in 11 states out West. Then it was on to the advertising department of Dell Publishing, which was big into comic books and paperbacks. By the time Roz met him, in 1956, restless Gene was ready to move on yet again, this time to the world of mopeds. According to a New Yorker article that detailed the growing trend of motor scooters as part of the metropolitan lifestyle, Gene was selling Italian Lambrettas and German Adlers for the most well-known moped store in the five boroughs and also editing Scoot, a monthly magazine dedicated to the two-wheeled vehicles.

When Roz talks about life with Gene in those days, it sounds very Mad Men.

Dallyn with Gene Pavey at a park, 1960 / Photograph courtesy of Dallyn Pavey

“It was all very exciting to me,” recalls Roz, now 85. “He would take me everywhere on the latest motor scooters. Gene knew all the people and all the places. We’d go here. We’d go there. And Paul Newman would be at the next table. It was thrilling.”

Alas, this Mad Men ethos spilled over into Gene’s life away from Roz and Dallyn, who came along in 1958. Gene was a womanizer. When Dallyn was three, Roz’s uncle in Atlantic City died, and Roz took her toddler to the funeral. Gene stayed home in New York. As Roz and her family sat shiva late into the night, some of her girlfriends, who always had their suspicions about Gene’s extramarital activities, convinced her to call home to see if Gene was there. The phone just rang. They talked her into calling again an hour later, and this time, he picked up. But there was another voice in the background when he did — a woman’s. While Roz was sitting shiva, her husband was sleeping around.

“Gene turned out to be a selfish and risk-taking guy,” Roz observes. “Knowing what I know now, the word is ‘narcissist.’”

Roz filed for divorce, and she and Dallyn went to live with her mom in Atlantic City. She scratched together a paycheck teaching ballroom dancing at an Arthur Murray studio and was fully expecting Gene to support Dallyn, but he barely sent a dime. Roz went after him in court, eventually leading to an arrest warrant with Gene’s name on it, when Dallyn was six. Except Gene wasn’t around for police to arrest. He had left the country. He fled.

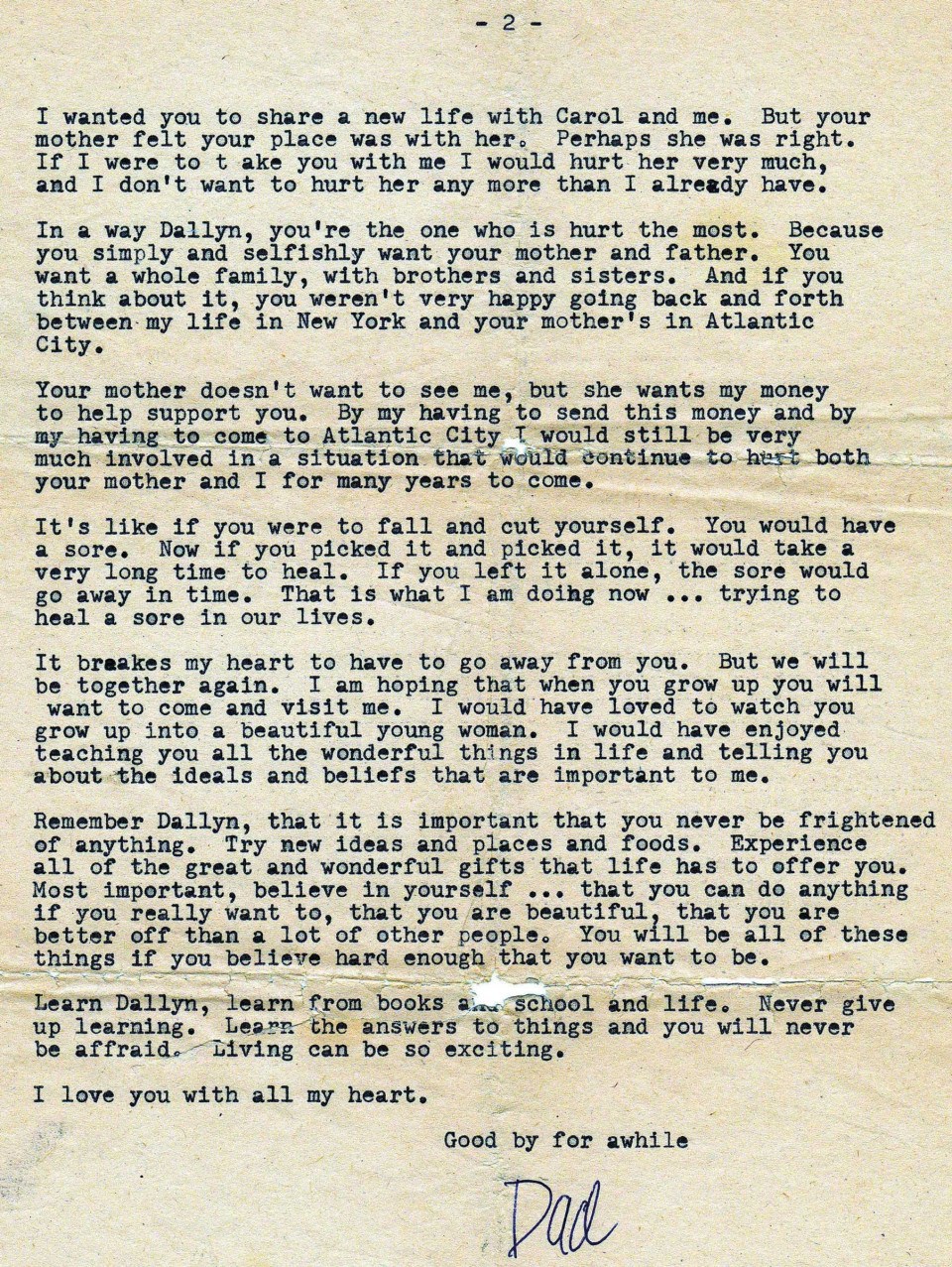

Gene gave Dallyn the news of his international relocation via a two-page typewritten letter — one of the many pieces of correspondence in the father folder she keeps in her office. “By the time you read this, I will be in Europe,” he wrote. “It breaks my heart to have to go away from you. But we will be together again. I am hoping that when you grow up, you will want to come and visit me. I would have loved to watch you grow up into a beautiful young woman.”

A letter to Dallyn from Gene

He paraphrased Thoreau. (“We have many lives to live.”) He offered some fatherly advice. (“Never give up learning. … Never be frightened of anything.”) And then, just like that, he was gone. Poof. Off to Europe with a new wife and a new career path: screenwriting.

“That is a heavy letter for a little girl to understand,” Dallyn says today. “His family felt absolutely terrible that he would just leave me like that. You have to keep in mind that this was the early ’60s. If you think about that time, most everybody had a mom and a dad. All of my friends had fathers in their lives. I couldn’t imagine why he didn’t want to see me. It’s really sad for a little girl to feel that way.”

Gene sent Dallyn another letter once he was settled in Europe, telling her that the continent on the other side of the world was filled with castles and that he had even met a “real princess.” He suggested that Dallyn learn some French, Spanish or Italian for the trip she’d never take to visit him in this far-off land. And he gave her the address of an intermediary in New York who could forward any mail to him. He asked Dallyn to write him back and tell him about her school, her friends. She didn’t. And Gene stopped writing.

Dallyn didn’t know it at the time, but the screenwriting plan didn’t pan out. It rarely does. For one reason or another, Europe didn’t work out, either. Nor did the second marriage. Gene and that wife, Carol, wound up back in the United States; then Carol left Gene and moved to Mexico. The details of Gene’s life from then — the mid-’60s to the start of the ’70s — are fuzzy at best.

As for Dallyn and Roz, they moved from Atlantic City to the Philly area, eventually settling in Narberth. Roz went to school for psychology and pursued a career in counseling, enrolling Dallyn in the Lower Merion school system. And it was when she was a sophomore at Lower Merion High School that Dallyn chose to pursue a relationship with her long-lost dad.

“I was 15,” remembers Dallyn. “I was dating a not-so-good guy. Actually, I had gone through a series of not-so-great guys. And I don’t know what it was, but I decided I wanted to find my father.”

Dallyn called her Uncle Steve in Brooklyn to say she wanted to reconnect with the family. An invitation to New York for Thanksgiving ’73 with her dad’s family — though not with him — arrived in her mailbox soon after. Her uncle sent her a letter and told her which bus to take, reminded her to pack a snack for the ride, and explained how to find him once she arrived at the Port Authority Bus Terminal in Manhattan. “Parking is impossible in that area,” he wrote. “So I’ll be in my car (red Dodge, black vinyl top, four door). I’ll have to keep going around the block.”

Dallyn remembers the visit vividly. The smell of her grandmother’s house was just as she recalled from when she was a young kid. There was the little bush out in front that now was a towering tree. They did the big turkey dinner at 4 p.m.

Dallyn can’t remember if she asked about Gene at all over dinner. She had a different strategy in mind. In the middle of the night, after the Thanksgiving dishes were done and dessert was polished off, while the rest of the family was asleep, she sneaked into the kitchen and rifled through the drawers near the old rotary phone, looking for an address book. She found one and paged through it until she found an entry for Gene. There was a phone number with a 305 area code, which she jotted down before going back to bed. She didn’t know at the time that 305 meant Florida.

Back in Lower Merion that weekend, Dallyn nervously dialed the number. She didn’t know what to expect. Was it even current? Would Gene be happy to hear from her, or was she just an unwelcome reminder of a past he’d tried to forget? She held the handset up to her ear and listened as the line trilled. A man picked up and said hello. Though she hadn’t spoken with her father in close to 10 years, Dallyn knew immediately that the voice on the other end wasn’t his. The man identified himself as a friend of Gene’s named Sanford.

“He knew who I was,” Dallyn says. “He knew of me; he knew Gene had a daughter. And he told me that my father was on a trip and that he would tell him I called.”

Dallyn says she waited and waited for Gene to call. She wonders if he did call back immediately — she’s still fantasizing 50 years later that he might have urgently wanted to talk to her, despite all evidence to the contrary — but that maybe she and her mom were out when he did. “It’s not like we had answering machines,” she points out. Or maybe Gene just wasn’t sure what to say after spending the majority of Dallyn’s life in absentia.

After a month or so, Dallyn had just about given up hope. Then, one day, the phone rang, and it was Gene, and the two spoke.

“We had a nice conversation,” Dallyn says. “He was very happy to hear from me. And me, well, I was beside myself.”

Gene made arrangements to fly her down to Miami so they could reunite.

“It was exciting,” she remembers. “I flew down, and he picks me up in the cutest little green Volkswagen Bug I had ever seen. He looked just great. He looked like a cool dad in his jeans and t-shirt.”

They went out to dinner. They went shopping. Dallyn stayed for about a week on that first visit, one of many she’d take over the next several years.

Roz says she didn’t debate long over whether to let Dallyn go to Florida to see her dad. “I was really happy for her. I knew she loved him and missed him, and there wasn’t anyone in her life that replaced her father,” she says. “Of course, if I knew about the drugs, it would have been a completely different story.”

Gene’s penchant for job-jumping and risk-taking followed him to Florida. In 1973, the year Dallyn tracked him down, he was advertising himself as a “marine photographer” in Miami newspapers. His company was called PhotoBoat, and he would show up with his Nikon gear and take pictures of you and your vessel. Whether you wanted documentation of a sailboat race you were in or just a living-it-up photo of you on your 100-foot yacht for personalized Christmas cards that would make your cousins jealous, Gene was your guy.

According to letters he sent to Dallyn in the second half of her teenage years — some signed “Dad,” some signed “Gene,” almost all annoyingly undated — he also had a company called the Oceaneers Club that ran dive trips in Haiti and Barbados. Then there was his bright idea to literally scoop up tropical fish in the open waters of the Caribbean and sell them to aquarium stores back home. At some point, he delved into the lucrative Southern Florida house-flipping market via a company he called Coconut Carpentry.

Photographer, carpenter, exotic-fish procurer — Gene did it all. There was always some new company, some novel scheme, a clever way to make a buck — and not all of it was legal. Gene sold pot. Lots of it. Dallyn thinks he sold speed, too. He was always surrounded by a young, tanned, attractive party crowd, and when Dallyn would fly down to visit, she’d jump right into the mix, partaking of whatever everybody else was doing. “It wasn’t that strange to share a joint with your father in 1976,” she says.

But Gene’s drug dealing caught up with him. Though court records were long ago destroyed, it appears he was arrested by the Miami-Dade police department in the mid-’70s and hit with a felony-level marijuana charge. That case went nowhere. But the Department of Justice somehow got hold of Gene, and he wound up at so-called Club Fed, the cushy federal prison camp housed on an Air Force base in Florida.

“I received a 90-day jail sentence which finally concludes my dope dealing exploits once and for all,” he wrote to Dallyn from the now-defunct Club Fed. “It’s really not so bad. There are no bars or walls or heavy-duty criminals. Matter of fact, there are some pretty nice guys here from all over the country.”

When Gene got out of the prison camp, he was living in a run-down, rat-infested bungalow that Dallyn was scared to sleep in. He would give her the bed while he slept outside in a van. “I was terrified,” Dallyn says. “The rats were everywhere, crawling up the walls. I would have been more than happy to sleep in the van instead.”

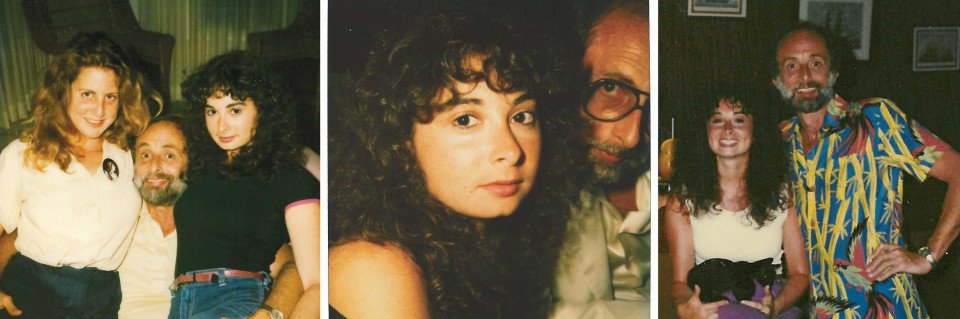

Dallyn and Gene Pavey and bride-to-be Melanie Mass (left) in 1982; together at a Coconut Grove restaurant in 1979 (center); in St. Barths with Gene in 1980 / Images courtesy of Dallyn Pavey

Gene may well have intended to leave the drug world behind, as he told Dallyn in his letter, but that’s not what happened. This was Miami in the late 1970s. Disco was huge. Sex was casual. And it was all fueled by that powdery white substance known as cocaine. The coke market was vast. And Gene had connections.

Life started to change.

“Gene was moving several kilos at a time,” says a business associate and friend of Gene’s in Miami who agreed to speak under the condition of anonymity. “He was working with one of the major Colombian distributors. It became easier for him to deal in coke, because it was smaller, lighter, and therefore easier to move around than marijuana.”

On one of Dallyn’s visits to Florida, she and that friend attended a dinner Gene hosted for some of his better customers and connections at a private club in the ritzy Coconut Grove section of Miami. There were 14 or so people there. One of them, both Dallyn and the friend say, was Griselda Blanco, accompanied by a bodyguard.

The notorious leader of the Miami branch of Pablo Escobar’s Medellín cartel, Blanco sat at the head of a multibillion-dollar drug-smuggling empire. If you wanted to move Colombian cocaine through Miami, all roads led to her. Known alternately as the Black Widow, the Godmother, and La Dama de la Mafia, Blanco, now long dead, is said to have been responsible for more than 200 murders. Legend has it that when she ordered a hit, she’d want every living thing in the house dead, not just the main target. All the children. The family dog. The goldfish. Blanco was brutal.

“She had a pretty, shall we say, ‘commanding’ presence,” remembers Gene’s friend.

What sticks out most about that dinner to Dallyn, other than the fact that this Colombian woman was there with a bodyguard, was the champagne. Bottles and bottles of Taittinger kept getting popped at the table. “I had never seen a bar tab that high in my life,” she says.

Gene’s cocaine business grew exponentially. Suddenly, he had a Porsche, a Cadillac, a posh and meticulously decorated home with a pool in an expensive neighborhood in Miami, and a cigarette boat, the long, narrow craft that was the go-to for Miami coke smugglers and dealers at the time. They were fast. Think Miami Vice.

Also new to Gene’s life was a blond teenager named Melanie Mass, whose well-known family owned restaurants in the Miami area.

“My dad would go to bed, and Melanie and I would sit up and snort coke all night,” Dallyn recalls. “It was crazy. My dad had just turned 50, and here I was doing coke with his girlfriend who was a few years younger than me.”

Gene and Melanie got married on May 16, 1982, at a private waterfront club in Miami, surrounded by friends, family, some Colombian business connections, and bodyguards. On the wedding video, a woman off-camera can be heard asking Gene, “Why do you need bodyguards?” “There’s a lot of wealthy people here,” Gene replies. “It’s a violent city, and why not take the extra precaution?”

Dallyn, Gene and Melanie all went back to his house after the wedding. The next day, Dallyn was due to fly back to Philly and had to get to the airport. Gene and Melanie never came out of the bedroom. Eventually, Dallyn demanded that someone come out and drive her. Gene opened the door, handed Dallyn $100, and called her a cab.

“And that was the last time I ever saw my father,” she says.

On June 22, 1982, Gene called Dallyn and invited her to join him and Melanie on a trip to the Abaco Islands in the Bahamas, where he intended to make a cash down payment on a second home. The trip was to take place over the Fourth of July holiday. Dallyn declined. She felt as though her relationship with Gene had changed since things got serious with Melanie, and she didn’t appreciate the way they’d treated her in the wake of the wedding. “It started out as a lot of fun,” she says. “But hanging out with them became a real drag.”

“Thank God she didn’t go,” says Roz.

Also invited on the trip was one of the bride’s sisters, Leslie, who was to fly into the airport in Abaco, where Gene and Melanie would pick her up after making the hours-long voyage from Florida in the cigarette boat.

Gene and Melanie left his Miami marina on Thursday, July 1, 1982. Andy Hancock, who owned the marina, remembers them packing up the boat and taking off. “Gene was a good customer of the marina and quite a character,” Hancock says. “It was clear what he was involved with, but I never judged. This was Miami in the 1980s. Running drugs in boats was not exactly uncommon.”

Weather and maritime reports from the local newspapers for that day and surrounding days show picture-perfect weather for a trip to Abaco: winds at 10 knots, seas at three feet. Not exactly dangerous conditions, though Hancock is quick to point out that a forecast is just a forecast, and that things can change quickly for the worse.

The couple reportedly headed north first, making a quick stop at a Fort Lauderdale marina for unknown reasons before setting course for the Bahamas. And after that? Nobody has a clue.

Leslie arrived in the Bahamas by plane, as planned, but Gene and Melanie never picked her up. The realtor they were supposed to meet sounded alarm bells with local authorities, but an unspecified family member reportedly intervened and said Gene and Melanie were surely fine and the realtor was just “overly apprehensive.” But by Tuesday — five days after Gene and Melanie left Florida in the cigarette boat — the Coast Guard confirmed that the couple was missing, and a full-on search ensued, involving the Navy, the Coast Guard, officials in both Florida and the Bahamas, and numerous private vessels.

Dallyn was working at the popular eatery Lickety Split on South Street when she got a call from a business associate of Gene’s saying her dad was nowhere to be found. She got on a plane two days later and spent more than a month in Miami. Melanie’s family enlisted private investigators and politicians to put pressure on the authorities, but not a single piece of useful evidence was ever found. No bodies. No wreckage. Nothing.

Dallyn at home in Wayne with a photo of her and her father, Gene / Photograph by Dave Moser

Dallyn firmly believes that Gene and Melanie were victims of the cartel, and in a 12-episode series of self-produced YouTube docu-shorts called Unsolved Mystery: The Fatal Journey, she points the finger at Blanco. That’s certainly a strong possibility. Gene was in business with the Colombians, after all, and more than a few people who did business with the Colombians didn’t make it out alive. Cocaine-related killings skyrocketed in Miami in the early ’80s, so much so that the city morgue ran out of space and had to rent a refrigerated truck for the overflow. Sometimes when you live your life in the fast lane, you get run over. Two of Melanie’s relatives who declined to comment on the record for this story ascribe to this belief.

There are other theories. Were Gene and Melanie hijacked by Bahamian pirates? Did somebody who knew there would be a lot of cash and possibly contraband on the boat set them up? Is the mystery of the Bermuda Triangle real, not just a campy urban legend? Could it have been something as benign as a boating accident? Or, perhaps the most intriguing explanation of all, did Gene decide it was time to retire — something the Colombians wouldn’t be too keen on — and find some hideout where he and Melanie could use suitcases full of cash he’d socked away to live out the rest of their years together?

“I’d like to think he’s in South America someplace, having a great time,” says Andy Hancock, the former Miami marina owner. “Maybe he’s still hiding out in Ecuador to this day.”

That’s what the psychics say — all three that Dallyn and her mom have reached out to over the years. That Gene “made it out.” Most men wouldn’t do that and leave their sole child behind, but Gene had already proven he was capable of desertion. As Roz says, he was a classic narcissist.

“Who knows?” says Dallyn. “We haven’t been able to find any proof of anything. But something tells me that there’s somebody out there who knows something more that they’re not saying. I just feel that with everything my dad put me through, I deserve some closure.”

Published as “The Disappearing Dad” in the July 2022 issue of Philadelphia magazine.