Post-COVID, Does Center City Have a Future?

Back in the day, Philly, like a lot of cities, banked on a revival of its downtown to spark new life. The plan worked fine — for Center City. But now that the pandemic has emptied offices, boomer residents are aging, and millennials are opting for the ’burbs, where do we go from here?

Photograph by Gene Smirnov

If you ever find yourself awake at three o’clock in the morning and would like some company as you fret about whatever it is you’re fretting about, you might consider reaching out to Paul Levy, the longtime head of the Center City District. There’s a chance — or at least a greater chance than there used to be — that Levy, too, is wide awake and staring at the ceiling.

“Worry” is a word Levy uses more than once as we sit one recent afternoon in CCD’s offices near Independence Hall, talking about what Center City has been through in the past couple of years — and what comes next. He balances that with sunnier phrases about downtown’s post-pandemic resuscitation — “positive momentum,” “going in the right direction” — but there’s still a sense of anxiety, or at least uncertainty, in his voice. When I ask, finally, what most keeps him up at night, Levy, who’s 75 and possesses a healthy shock of white hair, not to mention a wry sense of humor, pauses, then starts laughing from his belly.

“Only that I’ve spent the last 30 years of my life working on this — and now I might watch it unravel,” he says, still laughing. He looks at me. “That’s what keeps me up. A lot.”

Plenty has happened in the three decades since Paul Levy became the first — and, so far, the only — head of CCD, the business improvement district created by local honchos in 1991 as a way of making Philly’s core commercial corridor more attractive and competitive. At the time, the city’s downtown could charitably have been described as desolate and depressing, a place most notable for vacant buildings, anxious residents, business owners with their eyes on the ’burbs, and sidewalks that seemed to swallow up all human life after 5:30 p.m.

A makeshift dump during a municipal workers’ strike in 1986 / Photograph via Bettmann/Getty Images

A quarter-century later? It was as if a miracle had occurred. Even on a random Tuesday evening, you’d find throngs of people eating, drinking, shopping, going to shows. Perhaps even more remarkably, Center City and the neighborhoods adjoining it had become, thanks to an influx of empty-nester baby boomers and city-loving millennials, the trendiest place in all of Philadelphia to live, with the residential population zooming from roughly 155,000 people in 2000 to more than 200,000 in 2020. And it wasn’t just any schmoes who moved in. No; these were exactly the kind of educated and affluent (or at least pre-affluent) knowledge workers that cities everywhere were battling each other to attract.

And then? Well, then came March 2020, and it all changed again. Offices emptied out; restaurants and retail shops shut down; streets and SEPTA trains went people-less. A few months after that, property destruction amid the George Floyd protests upended things still more, freaking out even residents who might have agreed with the broader social point the demonstrations represented. More recently, an increase in crime — and in the random anecdotes one hears about crime — has added yet another layer of anxiety. All the magic Center City possessed just 27 months ago has been replaced by something else: unease, uncertainty, a concern that Philadelphia’s great success story of the past 30 years — the renewal of its downtown — might be at risk.

Whatever thoughts he harbors in the middle of the night, Levy, who moved to Philadelphia in 1976 after earning a PhD in history at Columbia, is philosophical as he discusses the state of things. “I’ve discovered there are two advantages of having white hair,” he tells me. “One is, I ride SEPTA for free. But the second one is that I’ve been through severe downturns before, when the gloom and pessimism were so all-encompassing that you couldn’t believe there would be a better future. And oh my God — the mood changed! And so a constant theme of mine is, do not fully believe the mood of the moment. It is the mood of the moment, but predictions made about the future in that moment can be very wrong.”

It’s a reassuring, and correct, sentiment. And there are positive signs when it comes to Center City. Residential real estate has more than held up during the pandemic, with prices rising over the past two years and a record number of new projects, backed by a record amount of capital, either approved or already under construction. In other happy news, restaurants are getting busier, some office workers are beginning to trickle back into town, and the streets aren’t quite as lifeless as they were a few months ago. And as Levy points out, Philadelphia’s downtown, which boasts a rich mix of commercial and residential life, is actually better positioned for a post-COVID comeback than downtowns that are nothing but a sea of (now empty) office buildings.

But after two years of pandemic, the truth is that Center City, like so much of our society, is probably never going back to what it was in March 2020. Too much time has passed. Too many new habits have been formed. Too many attitudes have changed. In fact, there’s a powerful argument to be made that thanks not only to the pandemic but to other trends having nothing to do with the pandemic, March 2020 actually marked the end of a four-decade-long chapter in Center City’s history — a period in which it thrived but much of the rest of Philadelphia didn’t.

Which raises the question: What kind of Center City — not to mention the rest of the city — do we want to build in the next chapter?

Nicole Marquis, the founder and CEO of plant-based fast-casual chain HipCityVeg, is, in many respects, emblematic of the Center City of the past couple of decades. She’s a millennial (age 40). She’s smart and entrepreneurial. (HipCityVeg, which began with a single location on 18th Street, has now expanded to D.C. and New York.) She’s on-trend values-wise. (“My life changed when I went vegan,” she says.) And she’s a believer in — and booster of — cities. Which isn’t to say that for her, as for so many people, the pandemic didn’t completely suck.

“Oh, I mean, we were pummeled,” she says when I ask her one day, via Zoom, what the past two years have been like. “Honestly, it’s been the most difficult two years of my professional life.”

Marquis vividly recalls the day in March 2020 that she was forced to shut down her restaurants (she also owns the plant-based cocktail bar Charlie Was a Sinner on 13th Street and the Latin-inspired Bar Bombón on 18th Street) and lay off the bulk of her employees. Emotion got the best of her as she talked to a line cook at the Broad Street location of HipCityVeg who’d been with her for five years — and whose job she’d actually been able to preserve: “He started to cry, and then I started to cry. And of course, we couldn’t hug; we had to stand, like, 10 feet apart. He said, ‘Thank you for keeping some of us on, because I have kids.’” She pauses. “It was so scary, and at that point I realized: I’ve got to jump into action.”

Nicole Marquis, shown at HipCityVeg on 18th Street, helped start the Philly Restaurants Coalition during the pandemic. / / Photograph by Gene Smirnov

One of the things Marquis did was help launch the Save Philly Restaurants Coalition, an amalgam of 50 independent restaurateurs representing more than 200 establishments that has advocated for unemployment benefits for restaurant workers and generally tried to drum up support for the beleaguered industry. Meanwhile, she also threw herself into reimagining her own businesses, converting them into operations mostly focused on takeout and delivery. “Pre-pandemic, sales for delivery and online were about 15 percent of revenue,” she tells me. “Now, two years later, they’re still over 40 percent.”

Marquis is hardly the only business owner whose world has been disrupted since the spring of 2020. Center City itself is a case study in disrupted-ness. Before the pandemic, downtown had a daytime pedestrian population of some 400,000 people, about 35 percent of whom were commuters. At the depth of the COVID lockdown in 2020, that number contracted by at least 70 percent, and as recently as March, the number of office workers was still off by 50 percent. Not surprisingly, it all had an economic impact. Lauren Gilchrist, managing director of research at Longfellow Real Estate Partners, estimates that the retail loss to Center City over the past two years now tops $1 billion.

And yet, as devastating as the pandemic has been to Center City, some observers say the property damage that accompanied the George Floyd protests — on Walnut Street, windows were smashed and cars set on fire — and the record homicide rate and growing sense of lawlessness citywide have been at least as challenging psychologically. “I think more damage was done to the core of the city from the violence than the pandemic,” says Allan Domb, the real estate guy who was elected to City Council in 2015 and now wears realtor and public-official hats simultaneously. “The pandemic was bad. The violence shook people to their core.” Domb points specifically to the middle-aged empty nesters whose presence — and dollars — have been crucial to Center City’s rebirth: “I see plenty of 55-, 60-, 65-year-olds in the past two years who’ve gone to either Florida or the Shore and hung out there. And they say: I don’t feel safe coming back to the city. I don’t see the lifestyle. I’m going to hang out where I am.”

You might roll your eyes at that stance — or, who knows, you might be reading this in your Naples condo — but Paul Levy says affluent boomers are a crucial ingredient in the Center City cocktail; losing them permanently would be a blow. “It’s the 55- and 60-year-olds who make corporate location decisions,” he says. “If we don’t wrap our hands around the quality of life, the safety issues, and the restoration of pedestrian vitality, we are at risk. You can’t build a city around 23- and 25-year-olds. You need the older demographic for purchasing power, for their leadership in business, for their support of arts and cultural organizations. All those things.”

Nearly everyone I spoke to for this story agreed that reducing crime — in the city writ large and in Center City itself — is the number one job facing Philadelphia right now. “Safety has surpassed COVID at this moment,” says Angela Val, head of Ready Set Philly, an organization created by the city and the Chamber of Commerce in early 2021 to help reboot downtown’s economy. “For any of this to work, the city has to be clean and safe.”

But job number two is nearly as crucial: getting as many of those thousands of workers who used to come into Center City every day to return on a regular basis. The problem? The longer the pandemic has gone on, the harder that’s become. If COVID had lasted, say, six months, it’s reasonable to believe the vast majority of downtown workers would have come back, and life would have resumed pretty much as normal. But after two-plus years of white-collar employees Zooming from home in their sweatpants, there’s a consensus that a hybrid work model will be the new norm. “The challenge with human beings is, we’re creatures of habit,” says Gilchrist. “Well, now we’ve been doing this for two years. So people are very much in the habit of not coming downtown for work.” If once there was a dream of having everybody back, all the time, the hope now is simply that companies will bring back many of their workers much of the time.

It’s possible. Comcast started bringing the bulk of its office workers in for three days per week this spring. While that still represents a pretty big drop-off compared to pre-COVID days, such a head count would likely be enough to keep Center City healthy — if it became the standard for most companies. But what if the return-to-work rate levels off at something less than that? What if instead of many workers coming in much of the time, it’s only half the workers half of the time? Or a quarter of the workers a quarter of the time? The ramifications of that could be severe.

Start with the impact on city government’s finances. Prior to the pandemic, about 45 percent of the municipal budget — some $1.5 billion — came from the wage tax, and 40 percent of that $1.5 billion came from non-residents working in the city. But since non-residents only pay the tax if they’re actually toiling away within the city limits, any significant reduction in in-office time by suburbanites could mean a massive hit — several hundred million dollars per year — to Philadelphia’s fiscal bottom line. (COVID relief money from the federal government more than covered the city’s butt for lost tax revenue in 2020 and 2021. That butt-covering, alas, has come to an end.)

Then there’s the potential impact on commercial real estate downtown. Yes, companies will still need offices even if employees are only here a few days a week, but will they need as much space as they had? In a survey by the CCD last winter, the majority of companies said they didn’t foresee downsizing. But that could change once the reality of hybrid work sets in, and real estate pros say they’re already seeing tenants who want to hedge their bets on leases. “There’s more focus on flexibility than economics,” says Josh Haber, a commercial broker with Binswanger, explaining that tenants are less concerned about the rent they’ll pay than the ability to get free from a lease if it turns out they just don’t need the space.

A significant reduction in the number of Center City office workers would, of course, hardly be good news for the already suffering businesses that cater to — and whose owners depend on — those workers. Fewer people in town permanently means fewer people eating lunch, sticking around for drinks, and whipping out their corporate credit cards for pricey business dinners. It means fewer people shopping on their lunch hours and taking yoga classes after work. It means less need for all the other services — from dry cleaners and shoe-repair shops to florists and pharmacies — that downtown workers once relied on. And it means fewer security guards and cleaning people. In short, the Center City economic ecosystem that was decimated during the pandemic might never really come back.

At a certain point, too, a permanent hybrid work model could impact the 200,000 people who’ve chosen to live in Center City and its adjoining neighborhoods. In fact, it already has. Real estate experts say that part of what’s driven Center City’s residential market over the past two years has been people who are working at home and suddenly find themselves lusting for more space — the studio dweller upgrading to a one-bedroom, the two-bedroom condo dweller now opting for a roomier rowhome. But what if the smaller nature of city housing stock in general becomes the issue, with a critical mass of buyers deciding it’s time for a four-bedroom colonial with a sweet home office in the suburbs? That would seem to be a particular risk if all the things that make city life attractive — great restaurants, bars and coffee shops, cute boutiques, the infectious energy of crowded sidewalks — have dimmed. Remind me again why we live in the city?

Paul Levy, architect of Center City’s resurrection, in his office. / Photograph by Gene Smirnov

All of this is, admittedly, a worst-case scenario, and there’s no specific evidence that it’s likely to happen. But it could, and what makes this moment particularly precarious are two megatrends that had the potential to upend Center City even without a pandemic. One is a shift involving the two generations most responsible for Center City’s rebirth in recent years — those empty-nester baby boomers, and city-loving millennials. Boomers, to be blunt, aren’t getting any younger. Those OG empty nesters who moved into the city two decades ago are now, in many cases, in their mid- and late 70s, and while I’m not trying to hustle anybody into the grave, the actuarial tables are what they are. The real problem is that the generation behind the baby boomers — Generation X — isn’t nearly as big, meaning the pipeline of emerging empty nesters making the move from Blue Bell to Broad Street isn’t as robust as it once was.

Of even bigger concern are millennials, who the CCD estimates are responsible for 75 percent of Center City’s residential growth over the past decade and a half and who make up more than one-third of the current downtown population (almost double their representation in the rest of the city). Collectively, millennials are now in their peak childbearing and child-rearing years, which means their attraction to the city could be waning as they seek out bigger houses, roomier backyards and better schools. The hope has long been that this would be the generation that stays in the city — and that may still turn out to be the case. But the pandemic clearly hasn’t helped. One millennial who’s already made the move to suburbia is Josh Haber, the Binswanger broker, who, with his wife, son and dog, left the city for the Main Line at the end of 2020. Haber says they’d always planned a move to the ’burbs, but pandemic life in the city — working from home, no great restaurants to escape to — “definitely expedited the process.”

The other big force potentially working against Center City is one that, years from now, will likely stand out as the most radical transformation brought on by COVID: the perfection of digital technology that makes geography all but irrelevant. One traditional feature of downtowns in general, and Center City Philadelphia in particular, has been the presence of physical infrastructure that doesn’t exist anyplace else in a region: rail lines and highways feeding into a central location, large office buildings, important public institutions, high-density shopping. But over the past 20 years, we’ve been creating digital infrastructure that potentially makes all that other infrastructure obsolete — and the pandemic was the first successful test run of the new system. Yes, we worked from home out of habit, but more than that, we worked from home — and shopped from home and ordered food from home and talked to friends from home — because we could. Before March of 2020, an Amazon Prime account, a Grubhub app and a Zoom connection were handy things to have. Today, they’re literal lifelines.

One person who sees clearly what’s happened is Nicole Marquis, who says the pivot she’s made to an online-and-delivery model is permanent in her business because it’s permanent in her customers’ lives. Two and a half years ago, she likely would have told you she was in the restaurant business. Today? “We’re a delivery company. We’re in many ways a tech company,” she says. And they aren’t going back.

There’s a case to be made that being untethered from geography — the fact that we can do pretty much anything from anywhere — could just as easily help Philadelphia as hurt it. After all, we have a nice city, and a relatively inexpensive one, and there’s no reason a certain type of person — “The group living in Center City is increasingly what I hear called the ‘laptop class,’” says Lauren Gilchrist — might not choose to live here even if his or her “job” is technically based in Houston or Seattle or Abu Dhabi. But it could also go the other way. You could just as easily live in the Catskills or Vancouver or the Philippines and have a “job” based in Philadelphia.

If the latter happens — if Philly does, in fact, see an exodus by the laptop class — it would be not only problematic, but ironic. Because those are exactly the people the current version of Center City was meant to attract, pretty much to the exclusion of anyone else.

The Center City we’ve been living and working in for the past couple of decades is, in many regards, the solution to a particular problem: What do you do with an already-built downtown when hardly anybody wants to be there anymore?

That was the situation Philly found itself in in the late ’70s and early ’80s. After thriving for much of the post-WWII ’50s and ’60s, Center City started to grow bleak as more people moved to the suburbs, more shoppers flocked to malls, and more companies shipped jobs to the Sun Belt or overseas. In the absence of people, the whole place started to feel depressing, and various kinds of illegal activity sprouted up.

“When I moved to 15th and Locust, there were a lot of hookers there,” Allan Domb tells me one day as I sit in his real estate office on Rittenhouse Square. Domb, who grew up in Fort Lee, New Jersey, bought a one-bedroom condo in the Academy House in 1978. “The hookers had moved over from 13th and Locust. That was a bad area. And it got really bad in the ’80s,” he adds. “It got worse.”

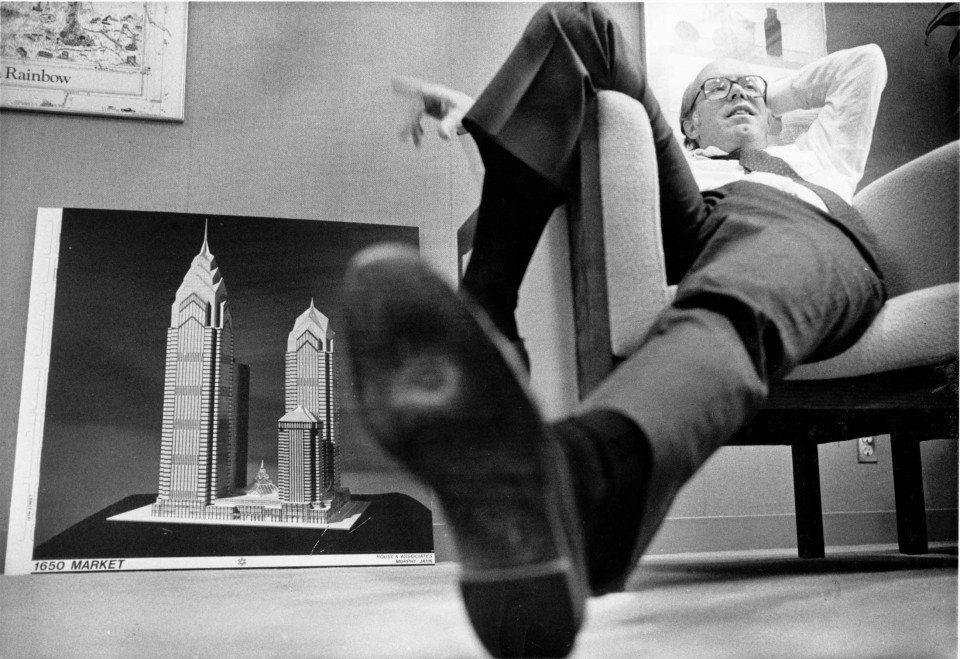

A construction shot of One Liberty Place / Photograph by Rick Bowmer/Philadelphia Daily News

The birth of modern Center City arguably came in 1984, when, after much civic arguing and wringing of hands, the city approved a plan by developer Willard Rouse to build two skyscrapers whose height would exceed, for the first time ever, Billy Penn’s hat atop City Hall. In retrospect, the fight over what would become One and Two Liberty Place seems both silly and quaint, but it was real — and intense. Those in favor of the new buildings said they were needed if Philadelphia was to have a modern downtown. Those opposed said the plan would alter the city’s character. Both were right.

And what would the characteristics of this new, more contemporary Center City be? Well, if the old Philadelphia was built on manufacturing and the old downtown was meant to be a central hub where people from all economic backgrounds (if not necessarily all races) could come to work or shop or play, the new Center City was a little more narrow in focus: It wanted to attract a particular kind of business and a particular kind of person. Because what choice was there?

“The prescription everyone followed, absent anything else, is that we gotta build the post-industrial economy,” says Paul Levy. “It was clear by the 1980s that our society was separating into knowledge-industry jobs and whatever the other thing is — what people called ‘smart jobs’ and ‘dumb jobs.’ Unfair, but that was the distinction.”

Philadelphia wasn’t the only place making this pivot. Other big cities — in fact, the nation itself — were making a similar shift, betting on the power of those smart jobs to carry the economy and lift everyone up. “Smart” America, Smart America told us, was the key to the future, and since Smart America was making most of the decisions, that’s the direction in which we went.

To a great degree, much of what followed in Philly in the next couple of decades aligned with that vision. After Rouse broke the Billy Penn barrier, numerous other skyscrapers went up, giving new homes to plenty of law firms and financial advisers (and, eventually, Comcast) while giving everyone else the sleek, grown-up skyline we enjoy now. The Center City District was born in 1991, out of the (correct) belief that if we wanted smart, sophisticated people to work in and visit our downtown, it needed to be clean and safe. Ed Rendell was elected mayor that same year and not only led the cheerleading for a new, better, more sophisticated Center City, but implemented policies and strategies to make it happen. He helped create the Avenue of the Arts and the Kimmel Center. He worked with the state and the Pew Charitable Trusts to create the Greater Philadelphia Tourism Marketing Corporation (now Visit Philly). He got behind a citywide initiative that would have an outsize impact on Center City: a 10-year abatement of city property taxes on any new construction or major renovation. It had exactly the intended effect: Empty office buildings got converted into apartments, condos got constructed, and the city changed.

By the time Rendell left office in 2000, Center City was effectively teed up for the two groups that would transform it: boomers and millennials who had college educations. And the city shifted to meet their needs and tastes. The restaurant scene exploded. The arts scene blossomed. Bike lanes got added. The streets grew lively every night of the week. And the smart people couldn’t resist it. Today, nearly 80 percent of core Center City residents have a bachelor’s degree or higher, and the average household income is $120,000.

It was all kind of thrilling, except for two problems. One was easy to see: gentrification. Particularly as more millennials moved in, the boundaries of change spread out to places like Fishtown and Point Breeze. Some longtime residents welcomed this; others were either forced out or put off by it, particularly because it typically brought cultural change. (As Luis Cortés Jr., CEO of Esperanza, has said, “You know you’re in trouble when there’s a dog-park license being requested.”)

The other major issue was harder to spot, though no less real. Part of the theory of the post-industrial economy was that by attracting people and jobs at the higher end of the spectrum, we would also create decent service-industry work underneath that. That’s not been wrong. As Paul Levy notes, more than half the jobs in Center City don’t require a bachelor’s degree. The problem? Too many of those positions, both downtown and citywide, just don’t pay enough to afford people a decent life.

Developer Willard Rouse in his office in 1985 with a rendering of his skyline-shattering projects / Photograph by Michael Viola/The Philadelphia Inquirer

As I sit with Allan Domb, for example, he starts firing off some eye-popping stats from the CCD. Between 2009 and 2018, Domb tells me, 29 percent of the jobs created across the U.S. paid $35,000 or less. But in Philadelphia during that same period, 61 percent of the jobs created paid that. The news isn’t much better for positions that pay between $35,000 and $100,000 — we do half as well as the rest of the country. And top-rung jobs that pay $100,000 or more? We do slightly better than with lower-paying positions, but not great.

“When you look at the backdrop of the last 10 to 20 years, we’ve done pretty well compared to what we’ve done before,” Domb says. “But that’s like being in a classroom of one and comparing yourself to your scores from the past. When we compare ourselves to other cities, we’re behind on almost every metric.”

Poke deeper and you see some other unsettling numbers. While nearly 80 percent of the people in Center City have four-year degrees, the citywide figure is just 25 percent. While Center City households earn $120,000 per year, the citywide annual income is $49,000. And then there’s race. As of 2020, 67 percent of Center City residents were white and just 12 percent were Black. In the city at large, 34 percent were white and 41 percent were Black.

Yes, we did create a fantastic Center City in the past couple of decades. It’s nice to be here. We should be proud of that. But if the premise was that attracting a flood of educated people would lift boats all across Philadelphia, that’s not how it’s worked out. What we did instead was create an affluent island separate and apart from the rest of the city.

And post-pandemic, the people on that island — well, there’s no guarantee they and their laptops want to stick around.

So now what? Even if its precise future is uncertain, Center City — our shiny trophy of the past three decades — is too valuable to just be left to fate. Which means getting creative about how we keep it vital.

One approach: Get people back into town by making transit free. SEPTA, whose ridership plummeted over the past two years, is partnering with Drexel, Penn Medicine and Wawa on a pilot program, called Key Advantage, that lets large organizations buy SEPTA Key Cards and give them out, no charge, to employees. “What it’s going to take for people to give SEPTA a try is if it’s free and therefore frictionless to attempt,” says Lee Huang, president of Econsult Solutions, Inc., which worked with SEPTA on the program. “So Key Advantage will be critical to encouraging both casual and regular use, which in turn creates the foot traffic and vitality that drive everything else.” (Huang, by the way, is enticing his workers back into the office by buying them lunch every day.)

Others are thinking even more broadly. “Really, now is the time for us to be looking at the future of cities and what we want them to look like,” says Nicole Marquis. “What will we offer residents and visitors so they can enjoy the city, so the city can stay vibrant?” She wonders aloud about making Center City even more of a playground, a place with fewer cars and more pedestrian walkways: “We’re one of the most walkable, livable cities in the country. Let’s embrace outdoor dining. Let’s support it even more, like the streets and alleys of Europe or Old San Juan or the Mediterranean.”

But it’s also clear that we need to consider more than just what’s good for Center City. That movement started even before the pandemic. City Council has significantly scaled back the tax abatement that helped spark downtown’s growth. The Chamber of Commerce kicked off a neighborhoods initiative. That push needs to continue.

One line of thinking suggests the pandemic might literally help spread the wealth in Philadelphia — that if Center City fades a little thanks to hybrid work, some of the other neighborhoods might benefit as residents stay home and patronize local restaurants and shops.

Others believe we need to be even more aggressive in leveling things out between the have-mores and have-lesses. City Councilmember Kendra Brooks recently introduced a proposal for a wealth tax in Philly. Under her plan, residents would have to pay the city $4 annually for every $1,000 in stock they hold. Brooks’s proposal would exclude money held in 401(k)s and pensions, and when we chatted, she told me she was open to excluding funds in 529 college savings plans as well. She said projections are that such a tax could raise $200 million per year — money she’d hope to see used for quality-of-life improvements across the city, like reopening libraries and expanding parks and recreation opportunities.

It’s a well-intentioned idea, and Brooks is passionate about it. When I ask if the tax might drive more affluent people out of the city, she pushes back, saying that studies of other cities have shown that not to be true; millionaires and billionaires don’t move because of taxes. As for the argument that affluent people shouldn’t be punished for their affluence, she says, “Equity is not built through trickle-down economics. This is what the city has been doing for decades.”

The have-more/have-less conundrum Philadelphia needs to solve isn’t, of course, just a Philadelphia problem; it’s an American one. The post-industrial economy the country started building four decades ago came with something of a subliminal message: Go to college and get a four-year degree and you’ll do fine — and maybe way more than fine. And if you don’t go to college? Well, we don’t really have a whole lot for you, but we wish you luck. The results have been what you might expect: Between 1983 and 2016, upper-income families saw their share of aggregate wealth grow from 60 percent of the pie to 78 percent, while middle-income families saw their slice drop from 32 percent to 17 percent — and lower-income families’ share fell from seven percent to four percent.

This is not to say, of course, that Philadelphia hasn’t caused some of its own problems. One of them, Allan Domb and many others believe, is the tax burden we place on businesses, specifically our business receipts tax (which takes six percent of a company’s revenue) and Pennsylvania’s relatively high corporate income tax (which takes about 10 percent). Added up, it amounts to the second highest tax burden of any city in America — behind only New York’s, twice as high as Chicago’s and San Francisco’s, and three times as high as in Boston and Atlanta. The result is that corporations that provide lots of jobs just don’t want to be here. (Of the 10 largest employers in the city, only one — American Airlines — is a corporation that pays taxes. Our giants, like UPenn and Jefferson, are technically nonprofits.)

“This is, like, third-grade math to figure this out,” Domb says. A year ago, he introduced a Council bill to reduce the city’s net income tax to zero over 10 years, which an estimate from Econsult Solutions said would create 100,000 jobs. Domb tells me he got eight of his 17 Council colleagues on board, but he needed nine. The bill died.

Domb isn’t the first person to suggest easing the burden on business. A few years ago, Paul Levy, along with Jerry Sweeney, CEO of Brandywine Realty Trust, authored a plan that would have slashed business and wage taxes in the city, making up the lost revenue with higher taxes on commercial property. But their proposal required a change to Pennsylvania’s constitution, and it eventually stalled in the state legislature. (Not helping: the fact that the Chamber of Commerce and City Council president Darrell Clarke both opposed the idea.)

All of it highlights one of the other difficulties Philadelphia has had over the decades: the lack of any kind of coordinated, coherent economic development strategy. Oh, we’ve got economic development organizations, like the Chamber and the Economy League and PIDC, but no one pulls their efforts into a whole that’s greater than the sum of the parts. That’s in contrast to many other cities — Pittsburgh and Houston, to name two — where a single organization is at the helm. “What we really need is a Marshall Plan for economic development,” says Longfellow’s Lauren Gilchrist, when I ask what she would do to fix Philadelphia.

When I ask Paul Levy how we might achieve more equitable growth across the entire city, he makes a couple of points. The first is that you can’t have equitable growth without first having, you know, growth. As he puts it, “You can’t have progressive goals without prosperity.”

His other point is broader. “Cities are not the product of trends,” he says. “Cities are an act of creation and will, and we need the will to build them in the right way. But that takes leadership, and we’re short on that in this city.”

I’ve known — and admired — Paul Levy for a long time, and as I sit in his office, I can’t help but feel empathy for his occasional sleepless nights. He remains bullish on Center City and Philadelphia, but at the moment, the future looks so … uncertain.

“There are two very famous quotes, and one of those is going to be true,” he tells me. “The first quote is that generals always fight the last war, and that means anything I’m telling you should be completely dismissed. The second quote is that those who are ignorant of their history are doomed to repeat it. One of those is going to be true, and that’s what’s at stake here.”

The robust state of Center City real estate suggests to me that our downtown and its adjacent neighborhoods could be fine in the short term. Even if people don’t want to work here, it’s clear they still want to live in the city center we’ve created. Of course, an influx of even more educated, affluent people won’t necessarily help other parts of the city, and it doesn’t assure anything in the long term.

Paul Levy knows, more than most people, that cities change, sometimes for the worse, sometimes for the better, then sometimes for the worse again.

“Our transformation has been remarkable,” he says, “but it’s fragile. And this goes back to those quotes. Am I just over-worrying because I’m fighting the last war, or do I know something, having been in New York in the ’60s and ’70s and watched things unravel? Could it happen again? I worry about that a lot.”

There’s reason to worry about that — Center City could unravel again. But there’s equal reason to worry that we could resuscitate our downtown and still be left with an unraveling Philadelphia. What’s that other old expression — the one about winning the battle but losing the war?

Levy has been very, very good at his job, and he oversaw what seemed like a miracle in Center City. Except, as he notes, it wasn’t a miracle at all. It was an act of will. As we look toward a post-pandemic Philadelphia, maybe that should give us hope: If we’re really smart about it, we could actually build a city where we all rise together.

Published as “Is Center City Over?” in the June 2022 issue of Philadelphia magazine.