David Morse on His Dark, Tony-Nominated Broadway Role That Was 25 Years in the Making

The actor known for roles in iconic shows from St. Elsewhere to True Detective talks about Mary-Louise Parker, the role he regrets turning down and his quiet life in Chestnut Hill.

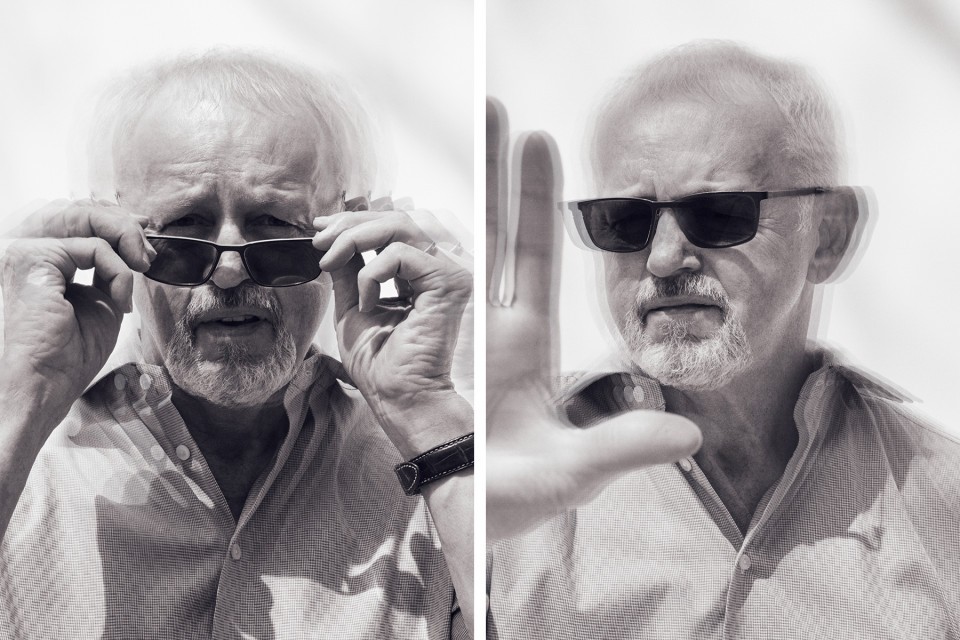

David Morse / Styling by Natasha Smee for Exclusive Artists / Photograph by Emily Assiran

Currently earning rave reviews (and up for a Tony) in a dark and disturbing Broadway play, veteran actor David Morse has been in the biz a long, long time. He has more than 100 credits to his name, including critically acclaimed TV show True Detective (HBO); award-winning movie The Hurt Locker; and, of course, his 1980s breakout hit, St. Elsewhere. Yet he’s managed to lead an impressively quiet life in Chestnut Hill for decades. We sat down with the 68-year-old father of three to hear his story — from losing it all in one of California’s biggest earthquakes to a few Sean Penn cameos to one major missed opportunity with Jordan Peele that he’s come to regret.

Congratulations on finally making it to Broadway with How I Learned to Drive, which was an early victim of the pandemic, right?

It was supposed to go into previews in late March 2020. And we shut down rehearsals on March 12th. We felt robbed. But COVID was screaming through the New York community. Just terrifying. The rehearsals felt so wonderfully alive and important. But then I got really sick. The virus was out there, closing in on all of us. I was in New York, of course, and somebody said there was a health clinic for entertainers near Times Square and suggested I go there. I could barely walk. I was seen by a doctor who wasn’t even wearing a mask. The place didn’t have tests yet, so they told me to come back as soon as they got them. I was the first one tested at that clinic, and we had to wait days for the results. Mine came back negative, but some of those early tests may have been quite unreliable. I don’t know. I had COVID symptoms for months. Now here we are, more than two years later, and it feels so important to be on the New York stage. The community is coming back to life and telling stories to each other and with each other.

For readers who may not know, this is a revival of a play you and Mary-Louise Parker1Parker had risen to prominence in the early ’90s thanks to roles in movies like The Client, Boys on the Side and Fried Green Tomatoes.x co-starred in off-Broadway in 1997. New York Times theater critic Ben Brantley raved about the original show and called you “simply superb, always fully invested in what is doubtless a disturbing role.” What a review!2Twenty-three years after his original review, in a 2020 New York Times theater season preview — for a season that wouldn’t happen — Brantley wrote that Morse’s and Parker’s “gentle but harrowing performances have never entirely left my mind.”x The playwright, Paula Vogel, scored a Pulitzer for the work. The show seemed to be such a big win and, indeed, still is: The New York Times recently declared that you and Mary-Louise deliver “crushing performances” in this new version. Variety says Mary-Louise plays her role with “shattering perfection” and calls you “equally brilliant.” I could go on. All this to say, why the hell did it take so long for this to get to Broadway? A 25-year break between off-Broadway and Broadway isn’t the typical business model.

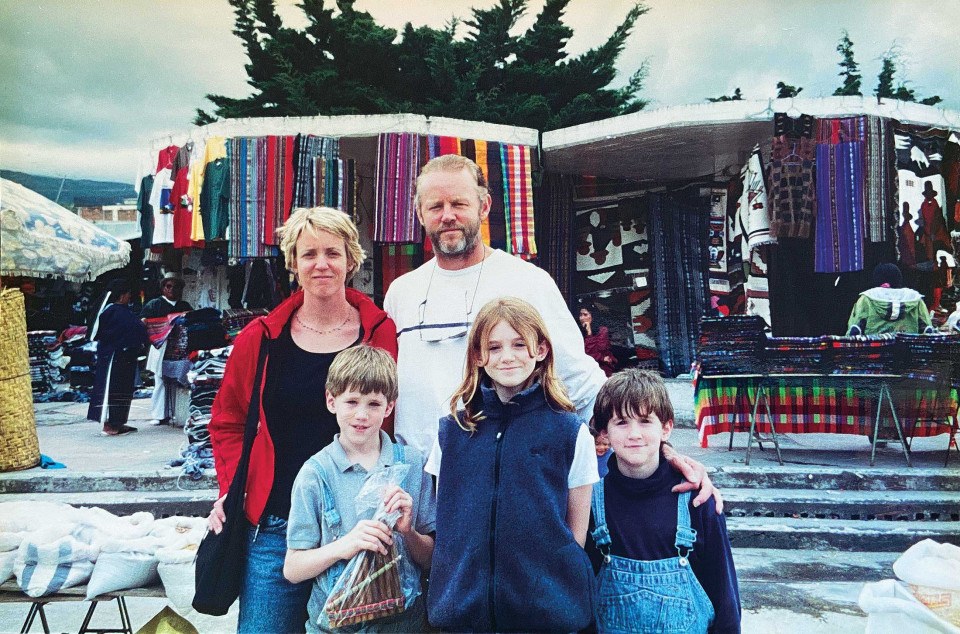

When we did it in 1997, I had been away from home for six months, and my wife, Susan, was here in Philadelphia with our children. My daughter, Eliza, was eight, and my twin boys, Sam and Ben, were five. It was a wonderful experience doing the play but really difficult for my family. Susan asked me not to do more plays while the kids were young. After about 10 years, the director, Mark Brokaw, said let’s do it again. But I hadn’t done a play since How I Learned to Drive and felt strongly that I needed to do something else first before returning to it. And Mary-Louise was busy doing Weeds on Showtime anyway.

I’m glad things finally clicked.

Well, we all agreed that one day, it would happen. We had all kinds of TV-series commitments. Our schedules kept not working. But the desire never went away. And then the Manhattan Theatre Club stepped up and wanted to do it on Broadway in 2020. And the way things had unfolded with our careers and children and such, we could do it. But then — and this was before COVID hit — we had to ask ourselves: Should we do this play? Is it the right play to be doing now?

I understand what you’re getting at, and this would be a good time to explain to readers that this is an unsettling play about a grown woman, played by Mary-Louise, dealing with some extremely difficult childhood memories surrounding her uncle, played by you. The name of the play would never give any of this away.

Let me tell you what happened when we first did this. Nobody knew what this play was about. We did it at the Vineyard Theatre near Union Square, and people would recognize our names and see the title of the play, and they would show up for the previews: “How I Learned to Drive — that sounds like fun!” And the writer3Playwright Vogel would later explain that part of her inspiration for the play was Lolita, the Nabokov novel about a man who molests a 12-year-old girl. She said she was shocked to find herself sympathizing with the molester. Critics have pointed out that she goes a long way to humanize Morse’s character, not merely portray him as a monster.x does have a wonderful sense of humor, which draws you in before anybody knows what’s happening. There is a very disturbing scene in the play, and as we approached that scene, you could feel the tension in the audience. Then when we got to the scene in question, people had to leave the theater. You could hear the chairs moving every single night as people would leave. But then the reviews came out. Everybody read about it. And it sold out for the entire run.

Trigger warnings weren’t a thing then. Should people be warned about the content of this play or others like it?

That’s a good question. Should we warn people? Possibly, because it is such a triggering thing.4In point of fact, there is no trigger warning, just a “mature content” warning and a recommendation that the show is for ages 13 and up.x I know people personally who found it excruciating — even people who knew what they were in for. But during the course of that run … People always wait after a show because they want autographs. But for this show, there were people who could not leave, because they needed to talk to somebody. They needed to be with people who understood. To cry with somebody. I don’t know what the answer is. I don’t know how much of a warning we would give, because at the same time, you don’t want to scare people away. This is profound. This is meaningful.

Mary-Louise Parker and Morse on opening night of the Manhattan Theatre Club’s production of How I Learned to Drive on Broadway on April 19th / Photograph by Bruce Glikas / WireImage/Getty Images

So back to the conversation you had about whether it was the right time to revive this, because I think that’s a very relevant question.

At the time we were discussing it, “MeToo” had just happened. So much had happened with that. And we had to decide: Is this still an important play, or are we just doing it out of nostalgia? And what we realized was that this was really important to us personally — to tell this story again. It is still important.

What did you do between COVID shutting down the 2020 production and then the team revving the show back up in 2022?

Susan and I had a van converted into this wonderful camper. We were on a waiting list, and it eventually got done. We flew out to Colorado to pick it up, and then we drove around the country from there. We literally went all over the country. It was amazingly freeing. One of the best experiences of my life.

I know you’ve been doing theater off and on in New York for many years. How did that all start?

I went to New York in the 1970s and studied with a man named William Esper,5Esper’s other famous students included Kathy Bates, Larry David, John Malkovich, Amy Schumer and Sam Rockwell.x who has become a legendary, world-renowned teacher. He died not long ago. He had a studio in New York on the third floor of this building, above a strip club. I had already been doing some acting with the Boston Repertory Theatre, but when I came to him, he said it was time to stop acting. “If you want to study with me, you stop acting and study for two years,” he told me. I couldn’t imagine doing that, but I did it, and it’s one of the smartest decisions I ever made. And then I was asked to do this play. I can’t figure out why. It was on 42nd Street. I can’t remember the name of the play or the theater it was in. But I definitely remember the neighborhood. In those days of the 1970s, this was a scary, scary part of New York City to be in. All of Times Square was. It was … it was … I don’t know.

Let me help you out: I’m picturing Travis Bickle in his cab in Taxi Driver, driving around an absolutely dismal 1970s Times Square.

Yes! Perfect! That’s what it was like. And so I was asked to do this play where I was an ancient Japanese monk. It was about samurai, and all the samurai were played by Black actors. I was the only white person. I don’t understand why the hell Bill let me do that play. I wore a bald cap, and yes, I wore Asian makeup.

How were the reviews?

I don’t remember. They had to be terrible.

Away from the stage, you’ve been in so many TV shows and movies, from St. Elsewhere in the 1980s to 12 Monkeys and The Green Mile in the ’90s to, more recently, Hurt Locker, True Detective, and Escape at Dannemora. You’re an instantly recognizable celebrity, and yet you’ve led such a quiet life here in Chestnut Hill for almost 30 years that I don’t think most people know you’re a local. How did you pull that off?

I don’t think I’ve ever qualified as a celebrity. Sure, people know who I am from the work I do, and depending on what I’m doing, there are different levels of recognition and excitement. When I did the TV show Hack, which was actually filmed here, it was over-the-top. It was tough on my kids, on the family. We needed privacy, but everybody feels like they own you, in a way. They feel free to join you at the dinner table when you’re out. But generally speaking, I’ve always had a pretty nice life here in Philadelphia.

Aw, you had to go and mention Hack, a show that was filmed in Philly before it was cool to film in Philly. I loved that show at the time and recently rewatched a few episodes online. Your co-star was Andre Braugher, on the heels of Homicide, which was huge for him. The creator, David Koepp, had some major successes under his belt.6Koepp’s previous writing credits included such Hollywood blockbusters as Jurassic Park and Mission Impossible.x Why did Hack fizzle out so quickly? I mean, who doesn’t love an ex-cop who becomes a vigilante cabdriver, searching the streets of Philadelphia for evildoers?

I really enjoyed doing Hack. But David wrote it to be a New York City cabdriver. He lived there and wanted the show there. I went to New York to meet with Les Moonves,7Moonves was forced to resign in 2018 amid numerous allegations of sexual misconduct against him.x who was running CBS at the time, and he wanted to do something that could compete with The Sopranos.8When HBO debuted The Sopranos in 1999, network TV executives saw the future: that cable could take over the TV sector, something they’d never dreamed of before. Hack ran from 2002 to 2004.x I told him I really wasn’t looking to do TV at the time but that if he’d consider shooting Hack in Philadelphia, I’d at least look at it. So he agreed to Philadelphia, and I did it. But David lost interest because he didn’t get his show in New York, and the writing suffered. And I was told this was going to be gritty storytelling, but Les kept pushing for more of a buddy-cop feel, which I didn’t want. Les also started enforcing casting choices. For my wife in the show, I wanted a person of color, but Les said,9Moonves’s lawyer did not respond to our requests for comment on Morse’s memory of this conversation.x “Oh, we can’t have that in the show.” Then they wanted to move the show to Toronto. “It’s too expensive to do it in Philadelphia,” this executive told me. “We could save half a million dollars an episode if we did this in Toronto.” I wanted to make the show work, but this was a Philly show. Philadelphia is a character. And I didn’t want to leave my family or take them to Toronto. At the end of the second season, the ultimatum was to do a third season in Toronto or just don’t do the show. I made my decision. I said, “I’m not going.” And so the show didn’t go on. It was stressful, to say the least.

I admire your dedication to Philly and your family. How did you all even wind up here? Most major entertainers have told me they can’t sustain their work unless they’re living in L.A. or perhaps New York. But you left the movie mecca to come here. Kind of backward.

We were living in L.A. and lost our house in the earthquake of 1994.10The Northridge Earthquake, as it was called, registered 6.7 on the Richter scale, making it one of California’s biggest. It led to dozens of deaths, thousands of injuries, and tens of billions of dollars in damage.x We had no place to go. We lost everything. I grew up in Boston. Susan had grown up in Chestnut Hill. She had friends and family here. We were actually married at St. Martin’s in Chestnut Hill in 1982, and after the earthquake, the church rectory was offered to our family. So we came to Philadelphia and stayed at the rectory while we figured things out. Our daughter Eliza was eight years old and in school here, and we said, “Let’s see if we can make this work.” And it’s just so beautiful, with the Wissahickon and the park. It’s a real community. Eliza went to Springside, and our twin boys went to Chestnut Hill Academy.

I can’t imagine how traumatic the earthquake must have been for you and your family.

I had recently come out of doing St. Elsewhere and was trying to transition out of TV. That was very hard to do at that time. Now, everybody goes back and forth. Back then, you got stuck in TV. But then, out of the blue, Sean Penn offered me the lead in Indian Runner,11The Indian Runner, in which Morse co-starred with Viggo Mortensen, was Penn’s directorial debut. Some weird movie trivia: Steve Bannon — yeah, that Steve Bannon — was executive producer of the crime drama.x which came out in 1991. That was amazing. And then came the earthquake. Our twins had just been born. It was the height of our stress. All of us were in the house when it hit. It felt like the end of the world. The end of my career. But then after we moved to Chestnut Hill, Sean called me again, this time to do The Crossing Guard, with Jack Nicholson and Anjelica Huston. I had a wonderful agent, and things progressed from there. And I have to tell you that Susan was almost saintly in her support of me doing all of this. I would be away for months at a time.

David Morse and family in Ecuador in 1999 / Photograph courtesy of David Morse

I know that Susan12Morse’s wife, actor Susan Wheeler Duff, has appeared in TV shows including L.A. Law, the 1980s Twilight Zone reboot, and Murphy Brown, in which she played the much-younger yoga-teaching new wife of Murphy’s dad.x has some background in the entertainment industry as well. Did the kids follow in their parents’ footsteps?

Eliza is a still photographer for movies and TV. Sam is doing music and working on films and living a creative life. They’re both in Atlanta, where the whole film industry has gone wild due to the tax incentives. It’s a real shame that we don’t have an equitable thing in Pennsylvania. And Benjamin is in Seattle, working for this electric-bike company called Rad Power Bikes that was already doing well but kind of went through the roof. When he joined, he was one of 12 people. Now, they’re all over the country and in Europe. So he’s out there climbing mountains and camping out.

I haven’t tried electric bikes. Not sure how I feel about them.

My wife is on a Rad, but I’m not. I’ve ridden bikes all my life. Out in Los Angeles, I was big into mountain biking and road biking. Coming here, I have the Wissahickon and still have my mountain bikes. I actually have this amazing local bike builder in Chestnut Hill, Drew Guldalian of Engin Cycles, who doesn’t believe in electric bikes. He’s very snobby about it, but that’s okay, because he’s making some of the world’s best hand-built bikes right here on Germantown Avenue.

We’ve talked about lots of the great work you’ve done. What about stuff you might not be so proud of?

[Laughs] I reluctantly did this TV thing with Ted Danson in 1981. It was called Our Family Business.13Our Family Business was originally shot as a pilot for a series but was so bad that it was released as a made-for-TV movie. One TV critic at the time called it “deadly” and gave it the lowest rating possible.x It was like a nighttime-soap-opera feel like Falcon Crest but a Los Angeles-Godfather type of story. I was the good son, the Michael Corleone, and Ted was the bad, bad son, the Sonny Corleone character. But a year later, he wound up on Cheers and I on St. Elsewhere. It worked out okay.

And you did get away from TV and into the movies for a while but then circled back to TV. How has the television business changed since the 1970s?

Back then, TV was just awful. I blamed it for all the sins of the world. Don’t get me wrong: There were shows that were pretty good, like some of the things that were coming out of Mary Tyler Moore’s studio.14Mary Tyler Moore Productions was responsible for such hits as WKRP In Cincinnati, Hill Street Blues, The Bob Newhart Show, and, of course, Moore’s eponymous shows.x Her studio was fostering a real TV writing community, and St. Elsewhere came out of that. But I thought that in general, TV was bringing down the culture. I was snooty and thought movies and theater were where it was at.

Every actor faces rejection. What’s a role you didn’t get that you wish you had?

That’s a pretty big list! [laughs] This one wasn’t actually a rejection, but … not long ago, I was offered a part playing a friendly but racist father who was murdering people in his basement. It was a little movie called Get Out.

Oh, no.

Jordan Peele is very, very funny and talented, but I had no idea what he was going to do with the script. It just didn’t feel right to me. So I turned it down. When it came out, Susan and I sat down to watch it, and in the first few seconds, I said, “Oh my God. What did I do?”15Bradley Whitford (White House deputy chief of staff Josh Lyman from The West Wing) took the role of the murderous dad and went on to play one of the main characters (Commander Joseph Lawrence) in The Handmaid’s Tale. “Get Out wound up being huge for Bradley,” notes Morse.x That movie was brilliant from beginning to end. This has eaten away at me since. But I made the decision I thought was right.

The TV and movie roles I’ve seen you in tend to be very, I dunno, dark. Is there any comedy in you?

[Laughs] For a while, everything I was offered was definitely bad father, bad cop, always some kind of eerily bad person. But I recently did The Chair, Sandra Oh’s Netflix series that came out in August. My character, the dean of the English department at this college, is still kind of heavy, but it’s definitely a comedy. We wound up shooting it during the height of the pandemic, and the protocols were brutal. I never saw the director’s face the entire time we were shooting.

You’ve done so much theater and so much screenwork. At this point in your life, do you have a preference?

The last play I did in New York was The Iceman Cometh. Denzel was the big name in it. It was a four-hour play with two intermissions and one of the most amazing casts I have ever been onstage with. I played the character of Larry Slade,16The New York Times said Morse, played his role as a disgruntled ex-anarchist with “ashen anger,” while the Hollywood Reporter noted that he brought “a haunted intensity to the difficult role.”x the only character that’s onstage the entire time. I start the play and I end the play. The whole time, I’m just thinking, “I get to be a part of this?” It’s just, it’s just … I feel like I’m stammering, and I’m afraid of what this is going to sound like.

Go for it.

There is something almost mythical between an audience and performers. When things are at their best, you can have moments like that in film and TV. It does happen. But nothing, absolutely nothing like in a theater. There’s something that transpires between all of us. You’re all in there together, suspending your disbelief, all agreeing to enter this world together. And there’s something that just goes back and forth between all of us. There’s … there’s … there’s just nothing else like it.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Published as “The Quiet Star” in the June 2022 issue of Philadelphia magazine.