Temple’s Journalism Dean Thinks We Should See the Carnage of the Texas School Shooting

In the aftermath of the shooting, Temple journalism school dean David Boardman wrote that "maybe it's time to show what a slaughtered seven-year-old looks like." Here, he explains why he thinks the change in media coverage strategy is necessary.

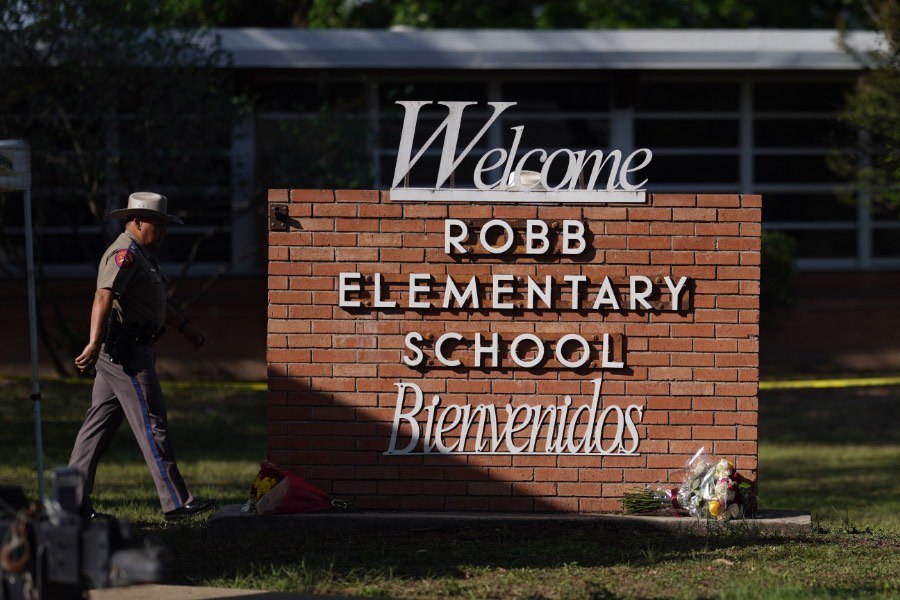

A law enforcement officer stands outside Robb Elementary School, where an 18-year-old gunman killed 21 people on Tuesday. (Photo by Allison Dinner/AFP via Getty Images)

On Tuesday, an 18-year-old with a legally purchased an AR-15 assault rifle and handgun proceeded to murder 21 people, including 19 children, at Robb Elementary School in Uvalde, Texas. This is now the deadliest school shooting this year, but far from the only one. There have been 27 school shootings in 2022 alone. The deadliest of all-time remains the 2012 Sandy Hook shooting in Connecticut that left 26 dead. This is life in America under the Second Amendment.

None of this should feel normal, and yet it is easy to identify the usual post-massacre cycle already underway. Republican politicians offer “thoughts and prayers,” while suggesting that, if only there had been a good guy with a gun, the tragedy might have been avoided. (In fact, there had been a good guy with a gun: a police officer working for the school district had encountered the shooter outside the school but failed to stop him, according to reports. And when cops did arrive on scene, they didn’t immediately enter the building, despite being urged to by onlookers, the AP reported.) Meanwhile, Democrats demand change, although it seems to matter little with the filibuster intact, as it appears it will remain—due to those very same Democrats.

In the wake of the shooting, a number of journalists have been reconsidering how to best cover school shootings and possibly disrupt the cycle of political inaction. One provocative idea floated by more than one person is that the media should publish photographs showing the bodies of the dead children inside Robb Elementary School. David Boardman, dean of Temple’s Klein College of Media and Communication, is one of those who believes this change in strategy is in order. “It’s time — with the permission of a surviving parent — to show what a slaughtered 7-year-old looks like,” he wrote in a tweet Tuesday. “Maybe only then will we find the courage for more than thoughts and prayers.”

I spoke with Boardman on Wednesday afternoon to hear more about how he believes the media should cover school shootings, why and when the media decides to publish gruesome photographs, and whether the press can really make any difference here. Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

You were previously the top editor of the Seattle Times. Walk me through how a news organization like that one would typically decide what to show and what not to show. The basic journalistic mandate to report and document what’s happening can oftentimes run up against, in moments of horrific tragedy like this, a different ethical question of what’s appropriate to actually show people. What’s the calculus?

For most mainstream publications, particularly when it comes to dead bodies of any age, there is a big red flag. Any good publication stops and has a reasoned discussion before they before slap any kind of photo like that into the newspaper and onto the web. Most often, the decision is to not do that, for obvious reasons of sensitivity, not wanting to re-traumatize family and friends who were close to the victim, or even others who might have been the victims of violence. Over the years, particularly with the printed newspaper, we used what we’d think of as the “over your cereal” test: Is this something that people are going to want to look at over their breakfast cereal in the morning as they’re reading the newspaper? That said, over the years, both in Seattle and elsewhere, there are occasions where the use of such photographs is deemed to be of enough value that it’s worth whatever offense you might cause, and again, with great sensitivity, particularly to the family of victims.

Let me ask you about the tweet that you just sent Tuesday. You wrote, “I couldn’t have imagined saying this years ago,” and went on to suggest that “maybe it’s time to show what a slaughtered seven-year-old looks like.” What has changed for you?

What really strikes me is that this is coming on almost the exact 10-year anniversary of a very similar elementary school shooting in Connecticut, and the fact that virtually nothing has changed. As a matter of fact, in many states, including Texas, it’s easier to buy assault weapons and for this sort of outrageous crime to occur. So I think we, as journalists, have to face up to the fact that our textual description of this sort of heinous crime, and pictures of these innocent young children, in their angelic form, isn’t moving citizenry and isn’t moving, certainly, the political machine the way it needs to be moved. So it seems to me that this is a case — and again, I would seek out permission from families to be able to do this, and I wouldn’t do it today or tomorrow, I might wait until next week or the week after — to graphically show the public and, by extension, the members of the United States Senate, what this sort of devastation looks like. In 1955, Emmett Till’s mother insisted that the casket of her 14-year-old son be open and publicly displayed so that America could see the outrageous cruelty of what white racists in the South were doing to Black men. Jet magazine took a picture of that, that picture circulated around the country and the world, and it marked a real change in the Civil Rights Movement. I think we’re at that point now.

You’ve emphasized that to run an image like this would be very much contingent on the consent of the parents or family. I’m curious when you think it’s appropriate to take and run images without that consent. You mentioned the Emmett Till example as one of consent, but there are a couple of examples that come to mind here in a different vein: the three-year-old Syrian refugee who was photographed washed up and face down on a beach, or Phan Thi Kim Phuc, the subject of the so-called “napalm girl” photo from Vietnam. There are even less extreme examples that you see all the time, like at crime scenes where a young person was murdered and the family is out on the streets, just devastated. Photographers are documenting that but they’re not asking first, “Hey, can I take your photograph?” So how do you decide when you do or don’t need that consent?

One of the considerations, and it’s relevant to the examples you just cited, is that I think news organizations have been, over the decades, much more at ease running pictures of people who are not Americans and, even within our country, Black and brown people in these situations, rather than white Americans. I think that’s led to some perverse equation on the value of human life. We’ve seen it not only in pictures, but even if there’s some sort of devastating typhoon in Indonesia and a thousand people die, it’s a small little headline, and if there’s some natural disaster in France, it’s a much larger headline. In a case like this, where you’re going to be showing something that is truly horrible, I think you really need to make every effort to try to get the families’ support for doing so.

You’re not the first one to call for a reconsideration of whether to show images like this. After Sandy Hook, the director Michael Moore wrote an article in the Huffington Post pointing out that some of the examples we’ve talked about already — the Emmett Till casket photograph and photos from the Vietnam War — prompted swift changes in public opinion. Public opinion already supports things like an assault weapons ban. So why do you think an image might make a difference in today’s world, where, again, 60 percent of Americans already support an assault weapons ban?

Yeah, there’s no question that it’s a political problem. And the challenge is at what level will political action and outrage outweigh the dollars that come from the gun industry and from particularly far-right Second Amendment-perverting organizations that have so many politicians just cowering? And it’s hard to predict: Would this make a difference ultimately or not? But if not, what would?

It sounds like your rationale for publishing an image like this would be in some ways less about the journalistic impulse of documenting the news and a little bit about trying to spur change. Is that a different, more activist approach to a news organization than you might have had previously?

I don’t like the term activism for journalists and for journalism, but I do believe that arming people with facts, perspectives, context, and truth that enables them to act, and not simply to observe, is an absolutely appropriate role for journalism. And if in fact 60 to 80 percent of the American public believes that these weapons should be banned and we should have greater regulation on guns generally and this compels [people] to act, well, that to me is an absolutely appropriate role for journalism.

Let’s say that a media outlet were to publish an image like this, and still nothing changes. Now that image is out there. So if that fails — and this is now into double-hypothetical zone — then how would you look back at the decision to publish the image? Would it be the wrong decision?

No, I wouldn’t look at that as a wrong or failed decision. But also, I wouldn’t assume that I would do it again in the future. I think this is a singular point in time right now. With the frequency of these incidents, coming upon the 10th anniversary of Sandy Hook, and the general resistance of the political body to respond to the clear preference of the people, I think it’s a particular point in time where this would be the right decision. It doesn’t mean it would become standard going forward. In fact, I’m quite sure that I would not want it be the standard moving forward.