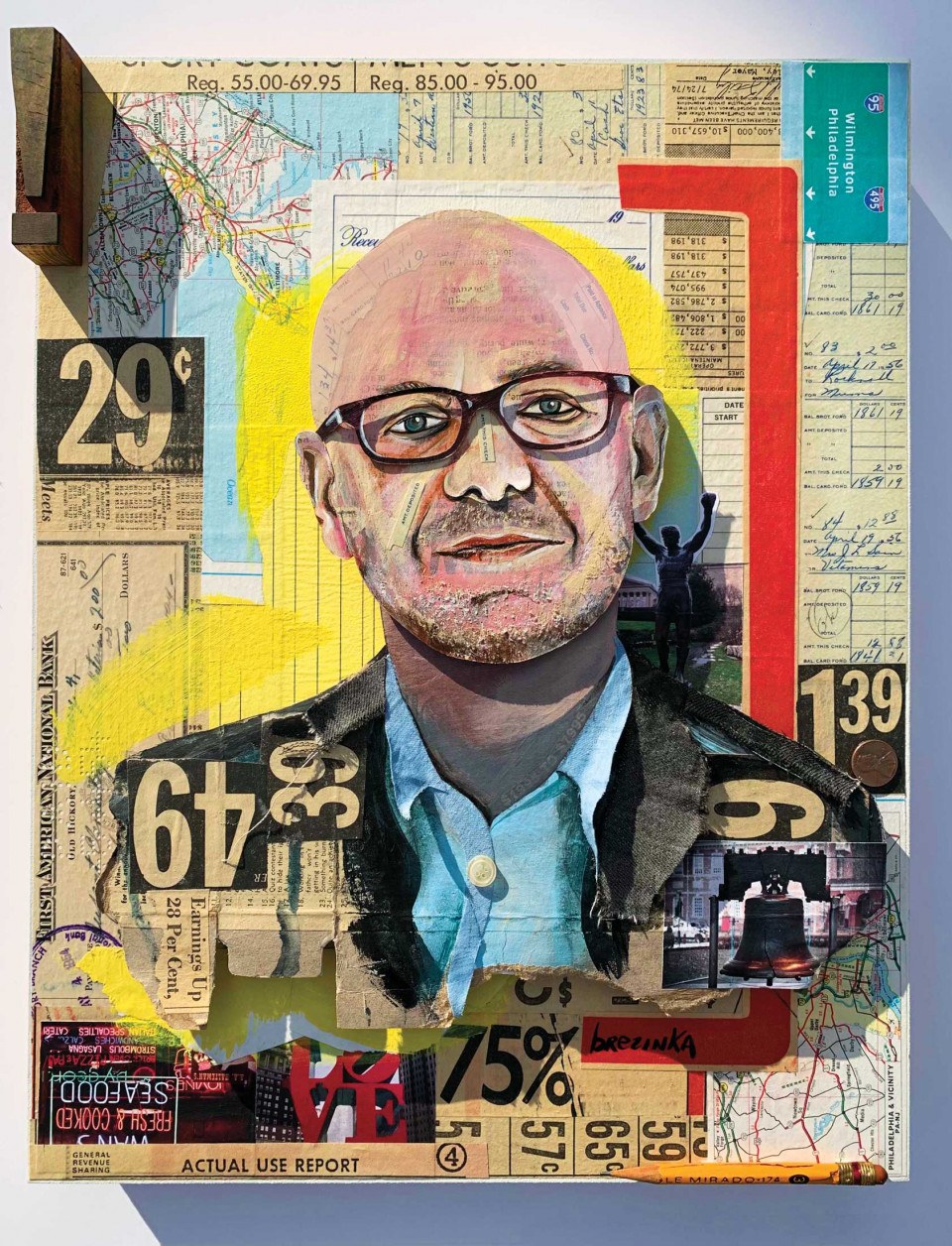

Michael Forman — the Philly Power Player You’ve Never Heard of — Is About to Make Some Noise

As CEO of FS Investments, he has quietly amassed powerful friends and lots of money. Now, he says, he’s finally ready to step forward and use all of that to fix Philadelphia’s problems.

Michael Forman. Illustration by Wayne Brezinka

“My dominant character trait is I’m really, really impatient,” Michael Forman says.

It’s a Tuesday evening in February, and Forman, CEO of Philly financial firm FS Investments, is giving a talk at the Center City co-working-space-meets-gym-meets-after-hours-hangout known as the Fitler Club. Forman, one of the private club’s founders, has a spot on the calendar reserved for his monthly “Lessons Learned with Michael Forman” discussion, a TED Talk-y symposium aimed at the ambitious yuppie business types who make up a good chunk of the club’s membership. Forman sits front and center in an airy industrial-chic room with concrete pillars and exposed ventilation ducts that normally serves as the club’s co-working space but has been converted into a kind of auditorium. He proceeds to hold court for an hour, walking through his life story, sharing his “thesis on life” (Luck is the intersection of opportunity and preparation), playing the business shrink to audience members seeking advice (“I feel guilty if I don’t work all the time; at what point can you be too disciplined?” one person asks), and pontificating on politics and the state of the city.

Suddenly, there’s a digression. The conversation has turned inward. Someone in the crowd begins grilling Forman about his personality.

“So you’re a persuader?” a guy in a dark suit asks.

“Yeah,” says Forman.

“What’s your energy level?”

“Mid to high.”

“What’s the number?”

“Eighties.”

“Eighties, yeah,” the guy says knowingly.

To everyone in the audience not employed by FS Investments, this interaction can’t make much sense. Realizing this, Forman, who’s 61, with a gray stubble beard, a bald head, and rectangular tortoiseshell glasses that give him the look of a Steve Jobs/Jeff Bezos hybrid, offers some context. FS employees, he explains, take a personality assessment that measures various attributes, some of which are linked to letters of the alphabet. Then Forman shares who he is: His “A” (dominance) is higher than average; his “B” (extroversion) is really above average; his “C” (patience) is “really low”; and his “D” (detail-oriented-ness) is “in the middle, so it moderates the extroversion and impatience.” Behold: the quantitative Michael Forman.

Whether or not you take stock in such abecedarian personality metrics, this much is indisputable: Michael Forman is someone you should know about.

He’s built an incredibly successful business in FS Investments and was one of the first to bet on the Navy Yard, siting his firm’s headquarters there nearly a decade ago. He has amassed, along with his wife, Jennifer Rice, one of the city’s great art collections and become a leading arts philanthropist, recently announcing a $3 million grant through the Forman Arts Initiative to support emerging artists of color and arts nonprofits amid the pandemic. He’s served on the boards of some of the city’s top institutions: Drexel University, the Barnes Foundation, the Franklin Institute. He’s got powerful friends: Drexel president John Fry, venture capitalist turned state banking secretary Richard Vague, Campus Apartments CEO David Adelman. He has the ear of politicians at multiple levels of government: Mayor Jim Kenney, City Councilmember Maria Quiñones-Sánchez, State Senator Vincent Hughes. But despite all this, Forman remains a relatively obscure figure — more white-on-white Robert Ryman canvas than Jackson Pollock. “I’ve tried to ride under the radar screen for a long time,” he says.

Forman with wife Jennifer Rice at their daughter’s bat mitzvah / Photograph courtesy of Michael Forman

That’s starting to change. For the past two years, Forman has been quietly convening a group of city civic and business leaders on Saturday mornings to talk about what they see as Philadelphia’s biggest issues and how they might solve them. (In the city’s siloed business community, this qualifies as a big deal.) If there’s a central concept to the Saturday Morning Group, as it’s known, it’s that business leaders need to reimagine their role in the city and exert considerably more influence in shaping everything from policy to public opinion. The same might be said of Forman himself. “I think one of the challenges in Philadelphia is that we’ve deferred to the political class to try to solve the problems that we have,” he says. “And I don’t think they’ve been successful over the last number of years.”

Forman has amassed an impressive roster of 70 or so people who agree with that proposition, among them Ryan Boyer, the new head of the building trades unions, who succeeded the immensely powerful (and now convicted-of-corruption) John Dougherty; George Burrell, former City member and onetime candidate for mayor; Madeline Bell, CEO of the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia; Alyn Waller, pastor of the city’s largest Black church; Della Clark, president of the Enterprise Center, a nonprofit raising capital to support Black-owned businesses; Keith Bethel, a former Aramark executive; Gregory Deavens, CEO of Independence Blue Cross; Jami McKeon, chair of the law firm Morgan Lewis; JoAnne Epps, provost of Temple University; Jane Golden, founder of Mural Arts; Keir Bradford-Grey, the city’s former chief public defender; Richard Vague; John Fry.

The group is doing more than just talking. Their conversations led to the founding last year of the Philadelphia Equity Alliance, a nonprofit not short on ambition whose website states the following aims: “Achieve health equity, reduce gun violence, improve educational opportunities, promote the Black and Latinx arts and entertainment community, and ensure government programs prioritize equity and inclusivity.”

No one can accuse Forman and company of thinking small. But for all the Equity Alliance’s lofty goals, it remains, not unlike Forman, mostly unknown. This seems to be by design. When I asked Forman if I could sit in on a meeting to observe how the group operates, I was told no, and when I asked for a full list of members, I was informed by a PR handler that this would constitute a “breach of the strict confidentiality that the group agreed to when it was founded.” One wonders how a group of people can task themselves with a list of priorities that basically amounts to solving every entrenched issue in the city and remain behind a veil of anonymity. If the Equity Alliance is going to accomplish anything — and for the moment, it’s too soon to say whether that will be the case — it’s going to have to do so in the public eye.

Nevertheless, the Equity Alliance is already a new player in the city’s political and civic landscape, and that inevitably prompts some questions. What will city leaders, especially progressives, make of a group of mostly middle-aged C-suite types lobbying them with solutions to the city’s woes? What does a newly engaged business class portend for the 2023 elections, when we’ll choose a new mayor — and at least a couple of City Councilmembers are likely to resign in order to run for that office? Can these businesspeople sitting around a table manage to turn words into action? And is previously anonymous, understated Michael Forman the one to make it happen?

“I don’t know if I’m the right guy,” Forman says at one point. “But I know that I care. I’m probably respected, in that people recognize that I don’t need to do this.” He’s wildly successful. He’s quite wealthy. “I don’t have any motive other than I care about the city,” Forman says. “And I want to see the city recover in a better way than it was pre-pandemic.”

It takes a certain kind of person to believe he can help fundamentally change the perspective and fortunes of a city, and Forman isn’t short on the requisite attributes — a mix of impatience, extreme competitiveness and discipline. He grew up in a North Jersey Shore town, the second of three children, with a stay-at-home mother and a father who worked in the stock market and had more bad years than good. “Watching him struggle certainly gave me more motivation,” Forman says, though it wasn’t the kind that made him want to follow in his father’s footsteps and succeed where Dad had failed. Forman dreamed of going pro in tennis — he played for the University of Rhode Island — and when that didn’t pan out settled for thinking he’d be a trial lawyer. “I was good at debate, good at arguing,” he says. It seemed a natural progression: There are few careers outside athletics that more clearly produce winners and losers.

Forman went to Rutgers Law School in Camden, then got a gig, not in the courtroom, but in corporate securities law, across the river at the firm Klehr Harrison, helping businesses with mergers and acquisitions. He made an impression. “His working style was unrelenting,” says Leonard Klehr, one of the partners at the firm and an early mentor.

Working at Klehr had benefits; not least, it offered an introduction to insider Philadelphia culture. Powerful people worked at Klehr — before John Street ran for mayor, his office was next to Forman’s — and powerful people hired Klehr. After a while, folks started coming, not to Forman’s neighbors at the firm, but to him. “My clients sought me out for my business acumen, my entrepreneurial skills and my judgment as much as for my pure legal skills,” he says.

In the early 2000s, after 15 years at Klehr, Forman started to have less interest in closing business deals for clients and more interest in making them himself. “I wanted to be the principal rather than the adviser,” he says. He left the firm and started investing in companies on his own. Eventually, Campus Apartments CEO David Adelman, who’d gotten to know Forman as a lawyer, came to him with an opportunity: He was thinking about getting involved in a new kind of investment firm, one that would, as Forman describes it now, “democratize alternative investments,” giving the middle class access to the kinds of fancy investment vehicles that are normally the domain of the über-wealthy. It was basically a page out of the playbook at Vanguard, the Malvern-based firm that popularized the concept of investments for the common man, but instead of hands-off index funds, FS would invest in things like corporate debt and real estate funds. Forman had no formal business or finance training, but he liked the idea so much that he liquidated everything else and became the first CEO of FS Investments. (“I’ve joked that I’m probably the only CEO of a successful finance company that’s never taken a business class,” he says.)

That was in 2008. As the market crashed, memories of his father were on Forman’s mind. FS probably should have failed then and there. But remember that life thesis: Luck is the intersection of opportunity and preparation. When the company launched its first fund, in January of 2009, the markets had already bottomed out. It turned out the timing was perfect. “We really had the wind at our back as a result,” Forman says. The firm now has $30 billion in assets under management, 300 employees, and more than 300,000 people invested in its funds, and it has, however improbably, cemented itself alongside the likes of Vanguard and Jeff Yass’s Susquehanna International Group as yet another financial-services behemoth in the Philly region. Leonard Klehr wasn’t surprised to see his former employee strike out on his own successfully: “Some people are just winners at what they do. They have the whole package.”

FS Investments ringing the bell at the NYSE / Photograph by Courtney Crow/NYSE courtesy of Michael Forman

As his business stature grew, Forman did something unusual: He stuck around. “I just care about Philadelphia,” he says. “I don’t want to sound pollyannaish about it, but I’m here because I chose to be here. Most of my friends live in Merion and Gladwyne.” His art collecting, which began with him and his wife buying cheap pieces at student shows in Philly, turned into a full-fledged side vocation: trips to Art Basel in Miami and New York galleries and auction houses. (Their collection, which focuses on women and artists of color, includes paintings by Kerry James Marshall, Rashid Johnson and Kara Walker and has been exhibited in the Philadelphia Museum of Art and the New Museum in New York City.)

There’s a version of this story that ends here: Michael Forman, rich dude on the periphery of public consciousness, mostly known for his art and for sitting on a bunch of fancy boards. But then, in 2020, the pandemic happened, and not long after that, George Floyd was murdered. “There’s some riots; the city is in a horrible condition at that time,” he says. He’d spent his entire adult life in Philadelphia, raising his three kids here, and yet now, he was “really nervous about the future of the city.” Like a lot of white people in May of 2020, he felt a sort of call to action, so he started thinking about what he could do to help.

The first few meetings of the Saturday Morning Group were informal — just five people on Zoom at 7:30 a.m. Forman had called up a few friends: Mike Gerber, a former state Representative for Montgomery County who’s now a corporate-affairs executive at FS Investments; CHOP CEO Madeline Bell; John Fry. Gerber brought along Ryan Boyer, who at the time was the only Black person in the group and didn’t know much about Forman. When he first heard that Forman wanted to meet with him, he thought he was about to get a pitch on how his union should move its pension funds to FS Investments.

Instead, Boyer wound up in a series of deep conversations about the state of Philadelphia. Invitees invited their friends, and Forman’s looked a lot different from Boyer’s, which was the point. “Mike’s job is to get, quite frankly, the people of his ilk in the room with more people like me,” Boyer says. “I populate it with voices that are rarely heard.”

Those early discussions had little to do with strategy. The attendees talked about inequity and systemic racism. About how Black Philadelphians own just three percent of city businesses despite making up more than 40 percent of the city’s population. They talked about wealth inequality — how nearly 25 percent of Philadelphians live in poverty. They talked about George Floyd. “We just gave them a lens into being Black in America,” Boyer says.

“What impressed me the most was, he listened,” Della Clark says of Forman. “He didn’t react. He never was emotional. He listened, and he received it all really well, and he allowed the minorities who came to the table to express some pent-up issues that they’ve had, not only with the City of Philadelphia, but also with America and with whites in general.” Forman describes the “raw conversations” as educational: “It’s not my life experiences, so to sit with people who are now your friends and hear about that really makes you think.”

Over the course of this dialogue, as Boyer and Forman emerged as the two leaders of the group, a new dynamic arose. “We went from just a group of people talking, sharing resources, to a real group that was going to be organized about doing the work,” Boyer says. He’d previously had his doubts — would this just be another “woke moment” that quickly evaporated? But the group kept meeting. And growing. Experts and political officials were invited to present about the city’s most pressing issues and how they might be solved. The group homed in on a few central focuses: gun violence, education, health-care inequities, supporting Black and brown businesses, and how to use the unprecedented infusion of federal pandemic relief funds to craft effective solutions. Then it formed the Equity Alliance, the entity formally tasked with turning the conversations from the Saturday Morning Group into action. (Boyer and Forman serve as co-chairs of the 13-member board.) The Equity Alliance hired McKinsey consultants to put together a presentation on how to grow Black and brown jobs and helped fund similar research at Drexel. Forman says he himself contributed in the “mid-six-figure level” to support the work. That was enough for Boyer to feel like Forman meant business. “You can say anything,” he says, “but Mike showed me by his actions that he’s committed to this cause.”

To most of the city’s business class — which is to say, to most Saturday Morning Group members — the venture feels like something profoundly new. “I don’t recall the business community ever coming together around equity,” Boyer says. Prior moments of convergence, like when business leaders courted Amazon’s second headquarters or developer Jerry Sweeney teamed up with the Center City District’s Paul Levy in a (failed) bid to make the city’s tax structure more business-friendly, were exactly the sorts of corporate-adjacent, limited-in-scope initiatives you’d expect businesspeople to care about. It was essentially Chamber of Commerce-style lobbying. The Equity Alliance, on the other hand, is focused on issues — gun violence, health care and education — that at first blush might seem outside the purview of business. Forman and Boyer, however, believe that solving entrenched racial inequities in Philadelphia will benefit business. In this sense, the Equity Alliance and the chamber share the same goals — it’s merely a question of approach. (They also share a number of members: Six of the 13 people on the Equity Alliance board serve on the board of the chamber.)

More fundamentally, Forman believes the Equity Alliance can help fill a structural gap that’s been holding the city back for years. He’s fond of pointing out that the majority of Philadelphia’s largest employers, like Penn, are nonprofits. (Comcast and Aramark are among the notable exceptions.) That’s great for civic engagement but not so great when it comes to building a strong, sustainable tax base, not to mention fostering an atmosphere of corporate philanthropy. We have nothing like New York’s Ford or Mellon foundations in Philly. (The Pew Charitable Trusts, our closest equivalent, is more of a think tank these days, Forman says.) But mostly, the preponderance of nonprofits has meant there hasn’t been an engaged business cohort, something Forman believes is an essential ingredient for success. “If you don’t have a vibrant city and you don’t have a vibrant business class, then your jobs leave the city, and you don’t have the tax base to support all the needs of the city,” he argues. He thinks this dynamic has left “a bit of a void in Philadelphia — an opportunity for business leaders to step up.”

Building trades council leader Ryan Boyer, who co-founded the Equity Alliance with Forman. / Photograph by Stuart Goldenberg

On paper, Ryan Boyer and Michael Forman make an odd couple, though they would seem to represent everything the Saturday Morning Group says it stands for. Boyer is Black; Forman is white. Boyer is a labor leader; Forman is a CEO. Boyer grew up in North Philly public housing; Forman’s dad worked on Wall Street. What they share is a fundamental belief in the city, along with a conviction that right now, it’s fundamentally broken.

It helps that they’re aligned on how to go about fixing it, whether through revisiting the Levy-Sweeney tax reform idea — essentially dropping wage taxes in favor of higher taxes on commercial real estate — or through better investment in commercial corridors in Black neighborhoods. (Boyer describes the Equity Alliance’s overarching philosophy as “pro-business, but pro-community.”) Most of all, they both believe a mind-set shift is necessary. “I’ve heard a major CEO say that the difference between Philadelphia and Austin is, when you go to Philadelphia and say, ‘I want to do this big idea,’ everyone will tell you why it can’t get done,” Boyer says. “And when you go to Austin, they’ll say, ‘Wow, how can I help you with that idea?’” Boyer and Forman want to make Philadelphia more like Austin. Or maybe Charlotte. In November, the North Carolina city’s mayor announced a $250 million public/private “racial equity initiative,” and the business community offered up $100 million in funding.

Forman isn’t flashy, but he has obsessive and freakishly energized tendencies — you don’t need a personality test to recognize this — that are well suited to solving problems. His wife describes him as “impatient and tenacious.” He gets up around four a.m. to do his morning reading, and his friends are accustomed to waking up to curated reading lists sent in the middle of the night. A plaque in his office bears a Jeff Bezos quote about how “speed matters in business” and many actions “do not require extensive study” — and he brings a similar drive to other aspects of his life. “When Michael Forman is talking to you, he’s hyper-present,” says longtime friend Damien Dwin, an investment firm CEO in New York City. “The wheels are turning at all times. You see it in his eyes, you see it in his body language, and you see it in the substance of what comes out of your interactions with him.” John Fry says Forman is “like a brother” — one of the few people who reliably check in on him just to see how he’s doing, with no ulterior motives. Once, when Fry was talking about wanting some new artwork for Drexel’s campus, Forman offered to lend some of his own collection. It now hangs on the walls of Fry’s conference room. “That’s a classic Michael type of thing,” Fry says. “‘You have an interest? What can I do to help?’”

If institutions are nothing but reflections of the people who comprise them, it’s possible to see a good deal of Forman in FS. The company touts “mind-set coaching, fitness consultations, and healthy on-the-road nutrition guides” as job perks. It offers a free 7:30 a.m. workout class — one that Forman religiously attends. He’s been known to challenge people, after the workout, to an extra contest — one more race up the stair machine? “He’d be upset if he lost and excited if he won, just like any competitor,” says Jason Ray, a former employee who bonded with Forman over their semi-fanatical gym habits. Outside the gym, salespeople at FS undergo an annual multi-round competition in which they perform a mock pitch for one of the company’s products before a panel of judges. Forman always serves as a judge for the final round. (Aside from bragging rights, winners have been known to get promoted.)

Forman brings a similar monastic discipline to his diet: He rarely eats sugar or gluten. Dining at restaurants with him can be an adventure, according to his wife — not because of the diet, but because of two competing impulses: his desire to try everything, and his ability to be perfectly satisfied after taking just one bite. (His wife and kids end up eating too much.) Is it any wonder, then, that Forman picked 7:30 for the Saturday Morning Group’s meetings (“It certainly tests people’s commitment,” he admits), or that the Equity Alliance has put on its plate just about every deep-rooted issue in the city?

If Forman likes to take one bite, in other words, it’s a very large bite. “When I get involved in something,” he says, “I tend to focus on it and be relentless in my desire to learn and try to impact things.”

These days, the Saturday Morning Group meets monthly, online or in person at the Fitler Club. Debate is encouraged. “A certain amount of tension is healthy,” Forman says, “because it forces you to discuss different points of view.” Once, in a conversation about supporting Black and brown businesses, one of the group’s members pointedly asked Fry what percentage of Drexel’s contractors are Black-owned businesses. “I didn’t know the exact answer, but I said, ‘I suspect it’s very few,’” Fry says. The person then told Fry, “Well, then, you’re really not helping to solve the problem here.” Fry says the deserved calling-out led him to go back to his staff and find out how to change the school’s contracting policies.

One subject that isn’t much discussed in the group, at least according to Forman, is politics. He describes both the Saturday Morning Group and the Equity Alliance as “decidedly non-political” — elected officials aren’t invited to join the group, and as a nonprofit, the Equity Alliance is barred from making campaign contributions. He sees the group’s work as a series of uncontroversial and apolitical propositions: “Even the far left and the far right will agree that you need to solve gun violence or that we should enhance access to health care.”

But what is politics if not a series of seemingly uncontroversial propositions — grow the economy; keep people safe — with divergent views on how to make them a reality? If you were to describe what the Equity Alliance has accomplished — and for a young group without much track record, this can be difficult to gauge — “non-political” wouldn’t be the first descriptor that comes to mind. Many of the Saturday Morning Group’s self-declared biggest successes have dealt very explicitly with city government. Boyer mentions that he lobbied Mayor Jim Kenney and his advisers on tax-policy reform — the result of which, he says, was the creation of a tax-policy working group he serves on that might finish what Paul Levy and Jerry Sweeney started. The Saturday Morning Group’s other hallmark achievement is its support of a gun violence intervention program known as GVI. It’s a targeted strategy, not without its critics on the left, that aims to concentrate law enforcement on the tiny fraction of people who commit gun crimes while also offering them social services like a decent-paying job. Boyer says the group has had “very high-level briefings” with Mayor Kenney, Council President Darrell Clarke and others. This year, GVI got a proposed $1 million boost in funding from the city and secured a $2 million state grant.

Part of the disconnect may just be a question of definitions: Forman seems to view “politics” mostly as donating money directly to candidates — something he personally can’t do locally, thanks to regulations regarding money managers. But politics isn’t just whom you support; it’s your worldview. And understanding what Forman believes is key to understanding the path the Saturday Morning Group might take from here. He defines himself and the group as “progressive Democrats,” then quickly adds, “The far left — we’re not those people. We’re not Helen Gym. We’re not AOC. We’re not there.” Instead, he name-drops New York mayors Eric Adams (a former police officer) and Michael Bloomberg (a former CEO and former Republican) as ideals. His federal donations further muddy the waters. He has usually supported Democrats, most recently Conor Lamb for Senate, but also donated to Mitt Romney’s 2011 presidential campaign, to both Pat Toomey and Katie McGinty in 2016, and to Mitch McConnell as recently as 2019. (Forman says his federal donations reflect FS Investments’ priorities, not his own.)

Forman seems to have conflicted views about his potential role in the upcoming mayoral and City Council races. Dabbling in politics would be an understandable impulse — the Saturday Morning Group is advocating for public policy, and one way to ensure you get heard is to help elect people receptive to your ideas. Forman says he’s been in touch with a number of the most often rumored mayoral candidates, including Councilmembers Derek Green and Quiñones-Sánchez, City Controller Rebecca Rhynhart, and grocery-store magnate Jeff Brown. But he doesn’t see this as necessarily political, saying of the mayor’s race, “I’m going to let it play out a little bit and see if I can impact things in other ways.”

There are rumors, however, that members of the Saturday Morning Group — motivated and influential as they are — are considering doing something quite political indeed: starting an independent-expenditure political action committee, which happens to be the one type of local donation Forman is allowed to make. (This kind of PAC doesn’t coordinate with any candidates or parties.) Boyer himself confirms that members of the group — including Forman — have had “side meetings” about how to “put our money together and really have a say-so on the composition of the next Council and the next Mayor.”

Forman denies having had those conversations with Boyer, but it shouldn’t come as a surprise that there’s a hard-to-pin-down quality to the man. This is new terrain for him, and the Saturday Morning Group is still working out strategic questions of how it might accomplish its gigantic goals. Meantime, the city’s political class is still working out what to make of him and the group. There’s a vague awareness of Forman and what he’s doing — and plenty of intrigue surrounding what he might do. What’s undoubtably true is that the next couple of years will be critical — for Forman, for the Saturday Morning Group, for the entire city. What remains to be seen is whether Forman will emerge as a leader who’s able to move the needle on the city’s problems; whether he and his groups will be embraced by politicians; and whether they’ll help pick the next cohort of politicians — whether, as Forman himself puts it, “we can follow through and make change.” We’ll have answers soon enough. Until then, on Saturdays at 7:30 in the morning, Forman knows where he’ll be.