Marc Lamont Hill on the State of Media, Defunding the Police, and His New Book

Outspoken and controversial author, scholar, Temple prof, activist, and Germantown bookshop owner Marc Lamont Hill returns with Seen and Unseen next month — but has plenty else to talk about.

Marc Lamont Hill / Photograph by Linette & Kyle Kielinski

Marc Lamont Hill has no shortage of opinions, and he’s not afraid to speak out — whether it’s through his latest book on race and justice, by voicing his objections to media coverage of Ukraine, or via an interview in the back of a MAGA-clad Uber. Here, the Germantown scholar, professor and author shares all of it — and what he watches when he’s trying not to think so damn much.

Hi, Marc.

[Lots of background noise.]

Marc? It’s so loud … Marc? Where are you?

Sorry, yes, I’m in D.C., where I just shot the show I do for Al Jazeera, UpFront. So I’m on the street and about to get in an Uber and hopefully make my train back to Philly.

Is Philly home now?

Philly will always be home. I’m back full-time now, living in Germantown. At one point in my life, I was between Atlanta, Philly, L.A. and New York. Every week.

Is Germantown where you grew up?

Nope. I started in Hunting Park, and then we lived in West Philly.

So back in Philly. And back teaching at Temple?

Yeah, man. That’s the main gig. Teaching will always be the main job. Anything else is an outgrowth of that or informs that. Teaching is my first love. After I graduated from Temple in 2000 and went to grad school at Penn, I came back to Temple as faculty in 2005. I moved on to Columbia and then Morehouse, but I was recruited back to Temple in 2017. Best decision I ever made.

How has the student body changed over the years?

The problem is that the students stay the same age, but I just get older and older. The cruel reality of being a professor. When teaching about popular culture, I used to be able to go to my CDs for material. Now, I have to do some serious research to know what’s poppin’ on the street.

We photographed you at Uncle Bobbie’s, the bookshop/cafe you opened in Germantown in 2017 as a labor of love. Is it still just that?

I’ve been fortunate to be able to transform it into a real business. If we broke even, or if I took a small loss each month, I would still keep it open. But the community really supports us. They buy the books, love the coffee, and appreciate the sense of community. Our motto is “Cool people, dope books, great coffee.” Most places don’t have all three. It’s a vibe.

On the subject of books, your seventh book comes out on May 3rd. Is book-writing getting any easier?

I don’t love … hmm. I “like” writing, but I love having written. The completion process is incredibly rewarding, but the writing is an intense, painstaking process. The world is so messy, and my job as critic, scholar and analyst is to help people make sense of the world. And since the world ain’t gettin’ no simpler, the work I have to do will only get harder.

In this new book, Seen and Unseen, you delve into how “visual media” have “shifted the narrative on race and reignited the push towards justice,” as your publisher summarizes it. When I think of visual media in this context, I think of the George Floyd video. Are we talking solely about caught-on-video instances of police brutality?

Great question. That’s part of it. But let’s look back in history. In the 19th century, journalist Ida B. Wells used photography to keep track of America’s lynching regime. Media and tech have always been part of the fight, but that role is changing as tech develops. And this book is trying to tell a story of not just the contemporary moments, but also the long arc of resistance.

Would this book exist if not for the murder of George Floyd in 2020?

I’ve been thinking and talking about these issues for a long time. Let’s look back at the beating of Rodney King and the role of tech in that. Put George Floyd aside, and that same week, Amy Cooper called the police on a Black man who was birdwatching in Central Park and falsely accused him of threatening her, all because he asked her to put a leash on her dog. That was on video. And we saw how the internet responded, outing Amy, exposing her, calling her job and telling them what she did. But the George Floyd murder obviously had a profound impact. We watched for more than nine minutes as a man was murdered. A modern-day lynching.

Imagine if there wasn’t someone there to catch it on video.

There have been a lot of horrific abuses through five centuries, and in modern times, enough of them have been recorded. Here, all of America was stuck at home during a pandemic and forced to witness this spectacle of George Floyd’s death. What if it had just been a photograph? Or what if we only had audio? This particular tech arrangement allowed us to witness that in a very particular way. We had to stare at his body for so long. But this also harkens back to when we had to stare at 14-year-old Emmett Till’s face, swollen many times over, when his mother insisted on a public, open-casket funeral for him after he was beaten and dragged into the Tallahatchie River on August 28, 1955, because of white-supremacist mob violence. The George Floyd video opened up a new kind of conversation — but this is a very wide and very deep story that doesn’t hinge on any single act of violence.

You mentioned Rodney King. You were 12 then, in 1991. Some 12-year-olds were very aware of what was going on in the world at the time. Others were playing Nintendo. Which were you?

Particularly in the Black community, even people who have no interest in politics or the daily news cycle had to come to terms with the Rodney King beating. For me, it was the first time I felt like America was forced to come to terms with the types of stories my friends and family told me since I was born. It reminded me of my father’s story of the Rizzo police beating him on Kerbaugh Street in Hunting Park in the 1970s. So for me, Rodney King wasn’t new information. But it was the first time America was forced to come to terms with anything like this. Black witness was always insufficient. Black people saying something happened was never enough. But now, it’s caught on tape. Who could deny he was beaten by police?

And yet look how it turned out.

Right. That was also the first time I felt confident in a victory. And by “victory,” I meant that the cops would be fired and prosecuted and sent to jail. So when the verdict came back, it certainly wasn’t what we were expecting. It was soul-crushing for me and many of my friends. We had a belief that this would work out. It got to! When it didn’t, it shifted the way I understood the criminal legal system and changed the way I understood the worth of Black lives in this country.

Has the movement that George Floyd’s murder set ablaze lost momentum? It’s been two years.

No. Movements change form. They aren’t just about people in the streets for 24 hours a day. Movements survive news cycles. Movements survive the liberal whites falling off the bandwagon. What I see now is increasing skepticism and wariness of police. People don’t just say, “Well, if a cop said it, it must be true.” And I also see an increased push for the defunding and abolition of the police. We could never return to innocence after George Floyd.

Your mentioning terms like “defunding” and “abolition” is sure to elicit some reader reactions. Some will say, “In a city where murder is out of control, how can we defund or abolish the police?” What do you say to those readers?

I say that for the last few centuries, we invested more and more in policing, and it hasn’t made us any safer or less drug-addicted or less vulnerable. We need a new way. Every year in government, we take money and move it to different places. We reallocate money to use it more effectively and efficiently. In the case of police, they are now being asked to be social workers, crisis-response teams, therapists and tax collectors. So even if you believe in police, you have to admit they’re being asked to do jobs they aren’t trained for and don’t have the capacity to do. So take money from the budget and hire therapists and social workers. That’s defunding. It’s not “Everybody’s gettin’ shot, so let’s fire the police and hope everything works out.”

But abolition?

When I think about abolition, I begin with a very fundamental question: What would the world look like if all our needs were met? And for me, abolition is an attempt to answer that question in real life.

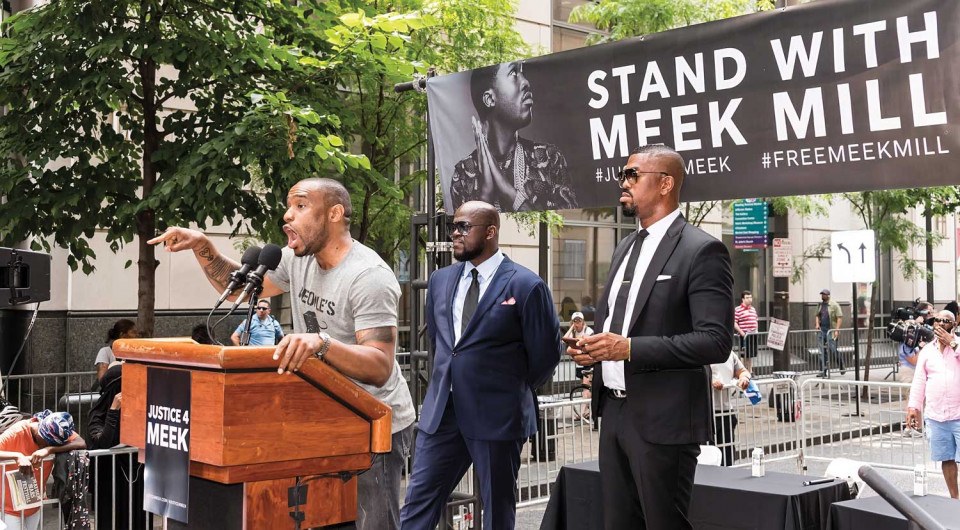

Hill speaks onstage at the Stand With Meek Mill rally on June 18, 2018. / Photograph by Gilbert Carrasquillo / WireImage/Getty Images

This month, your 2021 book, Except for Palestine, comes out in paperback. I haven’t read it, but —

It’s awesome. I can promise you. [laughs]

The gist is that many progressives aren’t so progressive when it comes to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Right?

Yes. Oftentimes, many of the same principles, ideas and values that we apply to other areas of our lives don’t make it to this particular issue.

And your remarks over the years about Israel and Palestine have had consequences. CNN fired you as a commentator. Temple publicly rebuked you. Some have called you an anti-Semite. What exactly is your position on Israel and Palestine?

I believe that — hold on one second. [pauses] I’m not avoiding your question; I’m getting out of an Uber. I have to run for a train. [car door closes; street noise] Okay, listen. I have to tell you this. I just gave most of this interview in the back of an Uber that was Blue Lives Matter-and-MAGA-adorned.

Oh, God.

It was amazing. I couldn’t wait to tell you, and I can’t imagine what the driver was thinking, hearing what I was saying. Okay, but now we’re into the “easy” stuff. Israel-Palestine. [laughs] People ignore that I am a scholar of the Middle East. I have a graduate degree in Middle Eastern studies. And I do a lot of research in the field. I don’t just weigh in as a citizen with random commentary. [long pause] Okay, hold on. I just ran for the train, and let me figure out who I’m sitting next to. Could it be worse than the Uber driver?

You could be sitting next to one of my Trump-loving relatives.

Wow. That must make Thanksgiving … awkward.

Oh, you have no idea.

Listen, my position is that I stand in solidarity with the Palestinian people in their fight for freedom and justice. But what happens there should all be decided by Israel and Palestine. Not outsiders. I am against any occupation of Palestinian territory, but I also believe the entire region must have freedom, safety, dignity and self-determination for everybody. I believe in the possibility of a shared land. I don’t think anyone has to leave. And I also know that anti-Semitism is something we must take seriously. We cannot deny that anti-Semitism is a persistent and even expanding problem both here and around the globe. We must fight anti-Semitism and stand in solidarity with Jewish people around the world.

You were on Fox News and CNN for years. Now, you’re on Al Jazeera and, until it abruptly shut down in March, the Black News Channel. Have you been blacklisted by mainstream media because of your outspokenness on Israel-Palestine?

Not at all. I think to believe that would be to believe there’s some media conspiracy. I was excited about doing the Black News Channel, and I’m proud to be with Al Jazeera. I am allowed to have an authentic voice and cover the stories I care about, and that means everything to me. I like where I am right now.

Your Fox News stint was in the mid-to-late-2000s. Was it as polarizing then as it is today?

Fox News has always been to news what the WWE has been to sports. Is the WWE a sport? It’s sport … adjacent. I think over time, though, Fox has given up on even the pretense of objectivity. They aren’t even pretending to be “fair and balanced” these days. They’ve become not just the communications arm of the Republican Party — they’ve always been that — but now, they are the communications arm of the extreme right. There’s a huge difference between Bill O’Reilly, whose show I was on many, many times, and Tucker Carlson.

If Fox News offered you big bucks today to rejoin the network, would you take the job?

No. Absolutely not. I could not work at Fox News today, on principle.

Black News Channel — did that have much of a white audience?

[Laughs] I had a lot of white viewers. In the two months before the station shut down, my show quadrupled its viewership, and a lot of the feedback and data showed that many white people watched it. They enjoyed the conversation. I covered international news. I covered debates on race. I covered entertainment. These are things white people care about, and so they watched it and engaged with it. Black people have been watching white news for a long time, and we managed to be just fine in our own community while watching what white people were doing. The world would benefit from watching a variety of vantage points and perspectives.

So what happened with the Black News Channel?

It wasn’t because of the number of viewers. We had a record number of viewers right before they announced the shutdown. But the bosses said it just wasn’t making financial sense. I can’t say much more about it, because it wasn’t my decision.

On one recent Black News Channel broadcast, right before the shutdown, you criticized the media on the Ukraine invasion, saying, and I’m paraphrasing, that things like this are happening all over the world to non-white communities, but now that a bunch of white European people are being bombed, that’s on 24/7.

Yes. When famine is in Africa or there’s violence in Chicago, we say, oh, that’s what happens there. But when the same things happen in places that are whiter, we respond with sympathy and outrage, particularly because our model is still whiteness. No one wants to see human beings harmed, but if you don’t fully appreciate and experience Black people as humans, it’s much easier to ignore their misery or suffering.

Marc Lamont Hill at Uncle Bobbie’s, his bookshop in Germantown / Photograph by Linette & Kyle Kielinski

I have to ask you about one very Philadelphia saga that you’ve inserted yourself in for many years — Mumia. The two of you are friends, and you’ve called him “one of the greatest truth-tellers that we’ve ever seen.” Do you believe he didn’t do it? Or do you just think he shouldn’t be in prison today?

I believe he is both factually innocent and legally not guilty. I believe he didn’t do it. And I believe that they didn’t make their case against him. To be even clearer, I would not support Mumia if I thought he was guilty.

Well, I’m sure I won’t get any emails about this interview.

[Laughs]

Some of the interviews I’ve done in this space recently haven’t been quite so, well, serious. I welcome the seriousness, but to go down one less serious path … what do you do when you’re not writing books, teaching students, speaking your mind, and pissing people off?

Until I ruptured my Achilles in September, I played basketball. A lot. Now, I have been grounded by my age. But I still spend my time at Sixers games. I am a courtside season ticket holder, and I can be seen yelling at opposing players and complaining to refs. Other than that, I watch lots of TV.

CNN? Fox News?

[Laughs] No news! No news of any kind! Reality shows. Silly stuff. Seventies sitcoms. I want laughs. I want the absurdity. It’s my best escape from this crazy world we find ourselves in.

Published as “On the Record: Marc Lamont Hill” in the May 2022 issue of Philadelphia magazine.