Trouble Telling Left from Right? You’re Not Alone.

Left-right confusion is a real, scientific thing. And it affects more people than you realize.

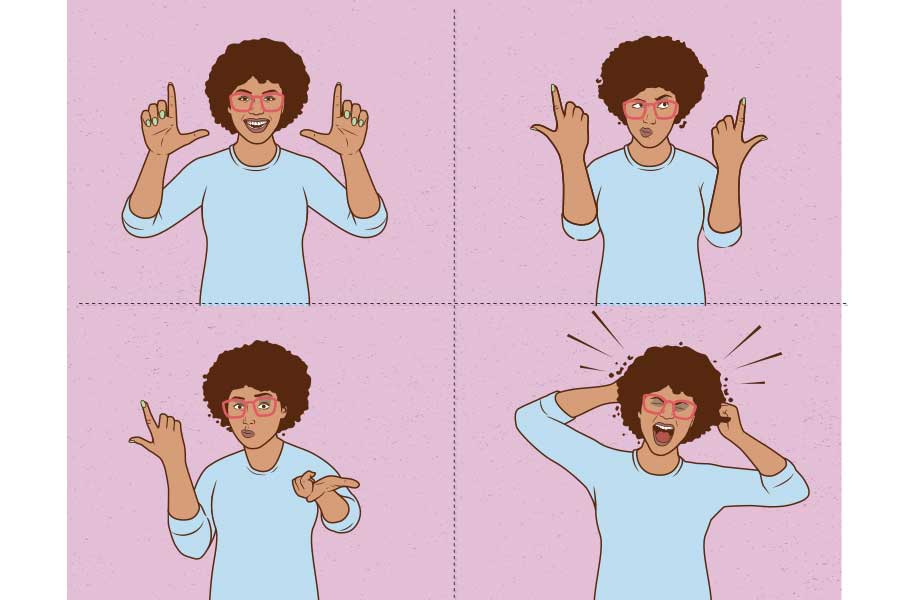

Left-right confusion affects 10 to 30 percent of people all over the world. / Illustration by Todd Detwiler

My husband and I are in the car, and he’s driving. I’m giving directions. “Make a left up there,” I tell him, pointing. “Just past the Wawa.”

“A left?” Doug says incredulously, seeing as there isn’t any road that way, only an empty field.

“I mean a right,” I say, correcting course.

“Oh. The other left,” he says sarcastically.

I guess he’s earned the, um, right. We’ve been together now for 40 years, some of which have gone faster than others, and in all that time, he’s never not had to double-check any directional instructions I give. The problem is that in a pinch, when forced to decide which way is right and which is left, I’m about as much use as Ben Simmons was to the Sixers. I can’t tell the difference. It’s all the same to me.

This isn’t the sort of thing one talks about, really. I’ve always considered it a character flaw, like Doug’s inability to see dirt on a carpet or my son’s failure to be married yet. I mean. My right hand’s my right hand. It’s the one I’ve always written with, eaten with, put on mascara with, for 65 years now. The ability to identify it as such would seem to be pretty simple: It’s the one you use every time you point to the left and say “Go right,” you idiot.

So imagine my surprise — not to mention my personal redemption — when I recently discovered, pretty much by accident (which is what my inability to distinguish directions always threatens to cause), that I’m not alone in my predicament. That far from being a consequence of my having skipped kindergarten, thus missing the vital shoe-tying lessons that might have helped with the problem, my condition affects between 10 and 30 percent of people all over the world and actually has a highly technical scientific name: “left-right confusion.”

Scientists study left-right confusion because while in my household, it’s mere fodder for Doug and the kids to mock me, there are situations in which its repercussions are more grave. Take, for example, the surgeon with instructions to excise a tumor from a patient’s left lung or replace a right kidney. People like me are why hospitals make those big magic-marker circles on you before putting you under. It’s also best if we’re not the ones drawing the circles.

Handedness itself is a curious condition. The world over, with surprising universality, 10 percent of humans are left-handed, regardless of geography, culture or era; so far as science can tell us, that percentage has remained unchanged since the Upper Paleolithic Age 10,000 years ago. We’re unusual that way. Lobsters, says Eric Zillmer, a professor of neuropsychology at Drexel, are about 50-50 when it comes to whether they have their big claw — “the one with the best meat” — on the right or the left side. Among our fellow primates, lateral dominance is more evenly distributed than it is in us Homo sapiens; some 65 to 70 percent of chimpanzees are right-handed, as are 75 percent of gorillas. Orangutans, on the, uh, other hand, are 66 percent left-handed. And way more primates than people are ambidextrous.

Which leads to the question: Why are there any southpaws at all? Why aren’t we all just right-handed? If you’ve ever befriended lefties, you’ve seen how they struggle with everything from can openers to scissors to swiping a credit card. Zillmer, who was Drexel’s athletic director for more than two decades before retiring last summer, cites sports as one example of why poor beleaguered lefties may have persisted: No matter the game, “Left-handed players are much harder to guard. There’s not as much advance coaching on left-handers, and opponents aren’t used to it.” It’s easy enough to extrapolate from that to what once served as sport for the young folk: warfare. A slingshot-wielder or axe-raiser or sword-swiper who favors the left hand has a built-in advantage. “In evolution,” says Zillmer, “it’s good to be innovative. And diversity is good.” Apparently, human left-handedness has managed to confer just enough of an advantage for one in 10 of us to outweigh its many, many inconveniences.

When it comes to my inability to distinguish between right and left, Zillmer assures me I’m in robust company. “It’s surprisingly complex to differentiate between them,” he says. “The brain has an enormous amount of neural structure dedicated to this.” Evolutionarily, he notes, it’s a relatively recent problem: “In the year 1000, the furthest a person traveled from home was maybe 10 miles. You walked out of the farm, and you either turned this way or that way.” There wasn’t all that much to think about.

As a rule, he says, humans don’t have the same problem telling up from down or front from back. But left and right are complicated. He recalls an expensive whale-watching expedition he once took on vacation: “You’re out in the middle of the ocean with no reference point, and a whale will breach for maybe five seconds. You’ve spent all this money, so you really want to see it. If the captain shouts out, ‘There! On the left!,’ half the people will look the wrong way.” As a work-around, the captain tells everybody the front of the boat is the number 12 on a clock and shouts, “There! At 10 o’clock!” It’s the same rationale for why sailors use “port” and “starboard” and not left and right.

“Look at our world,” says Eric Zillmer. “We’re constantly being bombarded with information. We used to live in caves! We’re still afraid of snakes and heights.”

Chances are, most of the people looking the wrong way for that whale would be women. The subject of wiring differences between male and female brains can be fraught, but experiments show that twice as many women as men grapple with left-right confusion. “Well, first off, it’s important to note that male and female brains are 99 percent the same,” says Zillmer. “We’re all human.” Which would be more reassuring if I didn’t know that gorilla DNA is 98 percent identical to ours. There’s evidence that women are more adept at language than men, a difference Zillmer says is only logical: “Women are childbearing. That’s the major difference. In the initial years of life, the woman is responsible for holding children, talking to them. Men are left out of that process, so language isn’t as important to them.” He offers an analogy: “If the brain is a hotel with 200 rooms, for women, language is in every room. For men, it’s in maybe 30 rooms.” This, he says, is why men are better at lying and more likely to be psychopaths (sorry, guys): “They have trouble expressing themselves verbally. When they say, ‘I love you,’ you have to know what part of the hotel it’s coming from.”

The Greek philosopher Plato, who was right-handed, held that hand dominance is learned. His student Aristotle, who was left-handed, claimed it was innate. They were probably both right. Neurologists have linked handedness with brain development: In righties, the left hemisphere of the brain is more heavily relied on; in lefties, it’s the right. Zillmer uses another analogy: “If the brain is divided into two train stations, the right side corresponds to the left side of the body. If you’re left-handed, you have more trains going to the right.” While the whole idea of left-brained vs. right-brained people has been overplayed in popular culture, recent research does indicate that there are certain functional asymmetries in the brains of left-handed people that aren’t present in right-handers. These have aided researchers examining various theories of the development of the lopsided handedness in humans: Did it evolve because early hominids walked upright, perhaps, rather than swinging from trees? Because hand gestures helped us to communicate? To enable us to more efficiently use tools? None of the hypotheses advanced so far have held up in testing. Or, as a study late last year summed it up, “The evolutionary underpinnings of handedness expression in our species remain enigmatic.”

It isn’t only women who are more likely to suffer from left-right confusion. The condition is also more prevalent as people age — and in heroin addicts, interestingly. “The human brain is the most complex system we know of in the universe,” Zillmer says by way of explanation for that finding. “It has a hundred million connections — that’s 10 to the 16th power! When people are addicted to anything, that complex system is impaired. With a system so intricate, when you introduce a powerful, strong chemical, it’s like tossing a wrench into a machine.” This is precisely, he points out, why we’re not supposed to drink and drive.

Left-right confusion is also a symptom of a rare disease known as Gerstmann syndrome that’s marked by it and three other distinct neurological impairments: difficulty performing simple arithmetic calculations; difficulty distinguishing among one’s own fingers; and difficulty writing by hand. It’s caused by lesions in the parietal lobe of the dominant brain hemisphere. The role of that lobe is to integrate spatial sense and navigation — what neuroscientists refer to as proprioception, or our consciousness of our own location in time and space. It’s what lets us steady ourselves as we cross a creek on stepping-stones — and what cops look for in field sobriety tests when they order you to touch your nose while your eyes are closed.

Historically, left-handedness has always been considered suspicious. To return to Plato and Aristotle, the former believed the condition was the result of bad parenting or inadequate education; the latter viewed it as the outward manifestation of an evil soul. In medieval times, the Catholic Church accused people of witchcraft simply because they were left-handed; centuries later, notorious 18th-century Italian criminologist Cesare Lombroso, bolstered by general societal disapproval of the condition, linked left-handedness to lawlessness and degenerate behavior, including alcoholism. Such influences explain why in schools, so many lefty students were literally forced to adapt to using their right hands.

Among these poor souls, Zillmer says, was his mother, who was born in Vienna in 1923. Naturally left-handed, she was pressured to conform to the right-handed norm. “She joked about it,” he says. “She was a good athlete. As a figure skater, she could spin either way. When she played tennis, she hit a forehand shot with either hand.” She became a mathematician — an occupation known for attracting left-handers. (The idea is that less brain space devoted to language leaves more room for other things.) For a time, Zillmer himself, who’s right-handed, studied math at a university in Germany. But, he says, “Math becomes non-verbal very quickly. The biology of my brain meant I was better at communication and socialization. You have to find your sweet spot.”

The left hand/right hand distinction is so ingrained in us that its footprints lie all over our language. The right is the right — all that’s true and correct and proper and holy. The left — well, the Latin for it is sinister, with all that word connotes. (The Latin for “right” is dexter, leading to such positive coinages as “dexterous”; French gives us droit, as in “adroit,” for right — and gauche for left.) And, undeniably, science has shown connections between left-handedness and troublesome conditions including schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, depression, anxiety disorders, autism, and intellectual disability. Yet many of the world’s greatest artists, writers and thinkers — Michelangelo, da Vinci, Charlemagne, Oprah, Julius Caesar, Jimi Hendrix, Ben Franklin, Albert Schweitzer — were lefties. Zillmer has a theory about that. Barack Obama was just the latest in a long list of U.S. presidents since the 1880s — James Garfield, Herbert Hoover, Harry Truman, Gerald Ford, Ronald Reagan, the elder George Bush and Bill Clinton — who were left-handers. (Earlier than that, we don’t have much hard evidence of handedness.) That’s eight out of 26 — well above the statistical odds.

“By nature,” Zillmer says, “if you’re left-handed, you’re special. You’re faced on a daily level with your handedness and have to deal with it. Malcolm Gladwell talks about ‘the advantage of disadvantage.’ Left-handers have an advantage because they constantly have to adapt and overcome adversity.”

Incidentally, speaking of politics, the reason we use left and right to designate opposite ends of the political spectrum is surprisingly prosaic. During the French Revolution, in 1789, members of the National Assembly who supported the king sat to the right of the president of the chamber; those who favored the revolution sat to his left. Down through the years, the terms that originally referred only to seating came to be applied to ideology. By now, they’ve been adopted the world over, with “right” referring to thinking that conserves the status quo and “left” indicating those who would prefer to shake things up a bit.

The way we think about our right and left hands isn’t completely universal. There’s a language spoken by a remote Aboriginal people in Australia that uses the cardinal compass points to indicate direction, rather than our self-referential (or, in science-speak, “egocentric”) differentiation between right and left. Should the Guugu Yimithirr want you to make more room on the car seat, according to the New York Times, “they’ll say ‘Move a bit to the east.’ To tell you where exactly they left something in your house, they’ll say, ‘I left it on the southern edge of the western table.’” Other languages that use similar systems have since turned up in, among other places, Polynesia, Mexico and Bali.

Just imagining the chaos this would create in my markedly left-sided head causes it to spin. And that’s not a good thing, according to Zillmer. Left-right confusion only intensifies when we’re anxious or under pressure. “We’re not perfect,” he reassures me. “In Western culture, we’re always trying to be perfect. It’s okay to make a cognitive error, even if it’s regarding something so simple that other people” — hello, family! — “belittle you for it.” He suggests I try saying something like, “Sorry! I have trouble with this!” and move on.

“Look at our world,” he says. “We’re constantly being bombarded with information. We used to live in caves! This is a completely different environment. We’re still afraid of snakes and heights. Our brains are lagging behind.”

My left-right confusion, he tells me, shouldn’t make me feel like I’m a freak of nature. “It’s a cognitive blemish,” he says. “It’s just along for the ride. I went to see the dermatologist recently about a blemish on my face, and that’s what he told me: ‘It isn’t malignant. It’s just along for the ride.’”

Besides, in the greater scheme of things, America might be a much better place if so many of us didn’t insist on drawing such sharp distinctions between left and right.

Published as “The Other Left” in the April issue of Philadelphia magazine.