The Icewomen Cometh: Why Dozens of Women from the Philly Area Are Taking Arctic Soaks in Winter

Some go daily. Some stay in for 10 minutes. And, yes, I reluctantly joined in the, uh, fun.

From left: Jackie Walther, Lorin Barry, Abby Schmidt, Jenna Cable, Adrienne Hamilton, Stephanie DeLuca and Meghan Moses enjoy a wintry dip. They are part of the Icewomen of South Jersey / Photograph by Shira Yudkoff

January 3rd could have been just another day in Philadelphia. Just another Monday. But thanks to a certain four-letter word that tends to send Philadelphians into full-blown hysteria, it was a little more exciting than most.

The night before, with local TV weather pundits forecasting that a snowstorm would arrive in the early morning hours, the panic-shopping at the Acme had commenced. Shelves that were already in questionable shape thanks to supply-chain hiccups were rendered downright sparse. By early Monday morning, numerous schools in the region had announced closings due to the first snowstorm of 2022.

That “storm” didn’t amount to much on our side of I-95. Here in Philadelphia, we saw less than two inches of snow, leading lots of parents to wonder why the heck their kids weren’t back in school after winter break. But snow blanketed South Jersey, with up to a foot in parts. No matter which side of the interstate you were on, it was a cold and blustery day, the perfect occasion to stay in bed and finally watch Don’t Look Up or binge the whole season of Yellowjackets, a warm beverage at hand.

But South Jersey’s Abby Schmidt had other ideas. It was her 41st birthday, and the artist and mother of two decided to celebrate on this frigid day by grabbing a couple of girlfriends and driving to a secluded river near Batsto, in the Pine Barrens section of the state. The murky body of water was what the average person might think of as a swimming hole in summertime, but most of us would never consider sticking a toe in when the air temperatures were below freezing and the “real feel” in the teens.

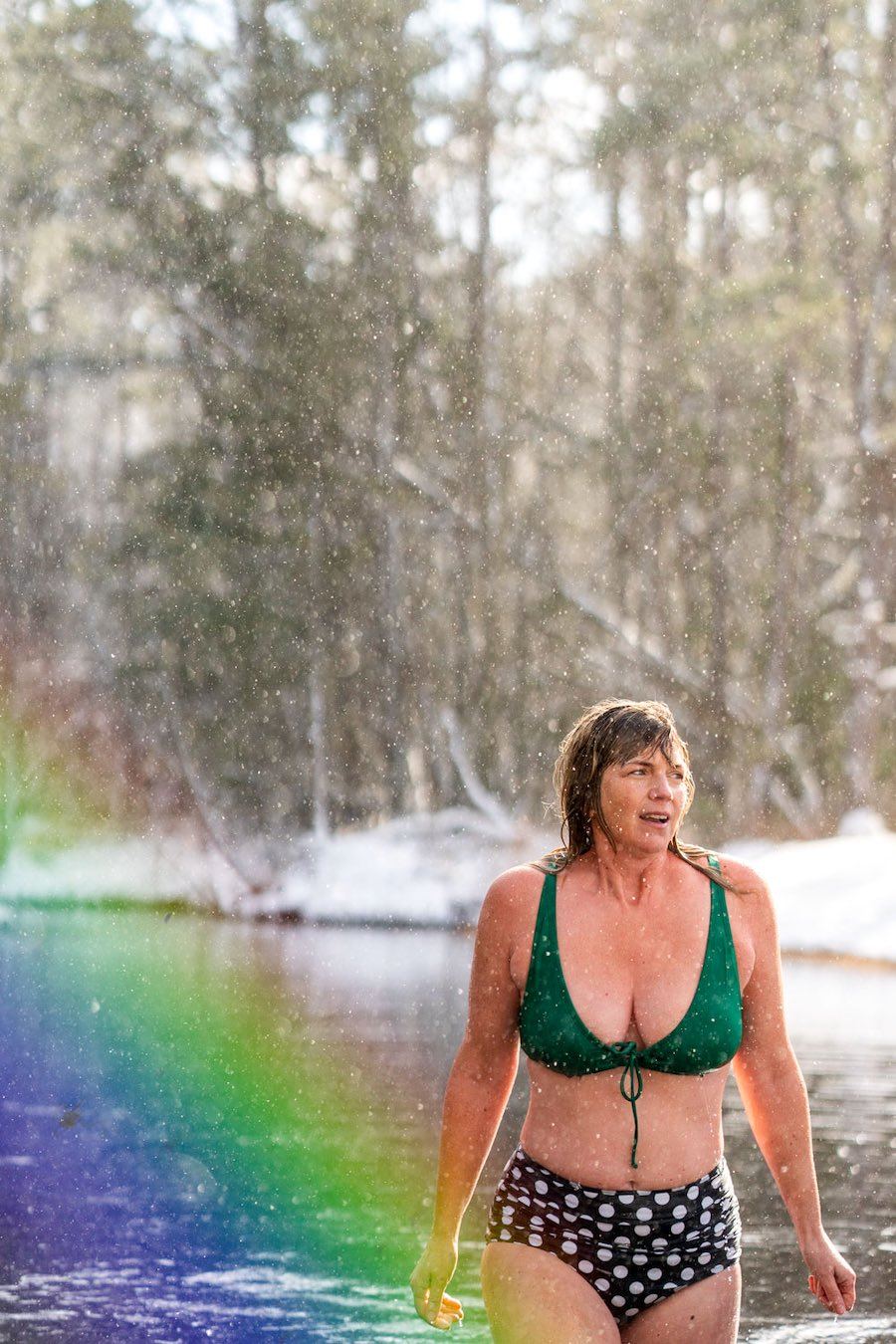

Schmidt did much more than that. She stripped down to black-and-white polka-dotted bikini bottoms and a green tie-up top. Then she walked right into the water, immersing herself, shoulder-deep, in the shivery bath, where she remained for several minutes. It’s a routine she’s been practicing for the better part of two years and, recently, almost every day while on maternity leave after surrogating a child for her younger brother.

“I’m still chilly,” Schmidt told me by phone about an hour after she emerged from the water that January day. “But I love it. It’s a complete full-body wake-up. Being an Icewoman has really changed my life.”

In the past couple of years, most of us have found ourselves forced — or at least heavily persuaded — to do something new with or in our lives. There’s the longtime waiter who’s now a cybersecurity consultant after spending 18 months taking online courses and landing a job in a more stable industry. The law student who, despite a distaste for children, took up nannying after she found the legal world’s summer job market all dried up. Then there are all those people with their pandemic projects, raising chickens, starting podcasts no one listens to, finally perfecting their beef bourguignon and baguettes, with home-churned butter for spreading, of course.

For Schmidt, it’s cold-water immersion that has not just occupied her but gotten her through most of the pandemic. And she isn’t alone. She and 50 or so other women from the area make up her loosely organized group known as the Icewomen of South Jersey. They hold official meetups the first and third Sundays of each month right up until the water approaches bearable, at which point they resort to backyard bathtubs filled with ice cubes. Schmidt, the de facto chairwoman, also announces last-minute one-offs. The twice-monthly dips are strictly for women only.

The name of the group isn’t just appropriate. It’s also a nod to Wim Hof, a Dutch athlete and motivational speaker nicknamed “the Iceman.” It’s unclear why, as a teenager, Hof jumped into a near-frozen canal in Amsterdam, but he’s been chasing chills ever since. He made it most of the way up Mount Everest wearing just shorts and shoes, only stopping due to a foot injury. He’s held world records for both the longest direct body contact with ice (his record-setting ice bath lasted one hour and 53 minutes) and fastest half-marathon run barefoot on ice and snow (2:16:34). Then there was the time he swam for 188 feet beneath a thick bed of ice in a Finnish lake for Dutch television, a feat resulting in frozen corneas that reportedly left him temporarily blind.

Hof, who’s a devotee of meditation, has his own breathing technique he’s developed. This and cold-water immersion are part of the Wim Hof Method that he or those he’s trained will teach you for a fee. There are expensive retreats. There have also been controversial claims that his method can alleviate the symptoms of everything from arthritis to Parkinson’s disease to multiple sclerosis. Critics raise eyebrows at the practice, because, you know, hypothermia and all.

But for Schmidt and many in her group, icy immersion is about mental health and camaraderie. Research shows the pandemic has had a disproportionate impact on moms, and Schmidt is no exception.

“This all started for me during the height of COVID,” she says. “I was so stressed out. And this … this made me feel alive again. It’s a natural high.”

We also know the pandemic has led to unprecedented levels of isolation, and Schmidt’s creation of the Icewomen gave her fellow members, most of them also moms, something to do together — notably, outdoors, where we’re all safer. And it lets them feel in control in an era when, thanks to erratic school closures, dicey day-care arrangements, and conflicting governmental advice, they otherwise don’t.

I first heard about the Icewomen via Paige Wolf, a communications consultant who recently moved from Center City to South Jersey. Wolf discovered the group through Instagram in November 2021.

Wolf assures me she’s not some Wim Hof fanatic. She’s just a 42-year-old mom who was looking for a fun outdoor winter activity to occupy her body and brain. “And skiing was not it,” she says. “So this is what I’m doing. When that cold water hits you, your first instinct is to jump back, and you have to fight through that. It’s empowering, like climbing a rope or giving birth or summiting a mountain. You find the strength. You power through it.”

Fairmount real estate investor Adrienne Hamilton, 44, was introduced to the Icewomen in December 2020 after she saw photos on friends’ Insta pages. She describes her time in the water as a sort of “forced meditation.” She’s been doing yoga for years but has found herself unable to clear her head during practice the way you’re supposed to.

“I am somebody with a super-active mind,” Hamilton explains. “I am not a good quieter of my mind. But when I get into that water, everything clears out immediately. It’s impossible to think about anything else.”

Hamilton also credits the Icewomen with sating the “thirst for community” that she and so many others have experienced during COVID. And wellness coach Erika Gleason of Manayunk says her “wild dipping,” as she calls it, has improved her self-image and body consciousness.

“I have the body of a 42-year-old woman with two kids,” Gleason tells me. “And it used to be that I’d be in a bathing suit on the beach feeling very self-conscious about my stomach. But then I did this, and it really makes you feel good about your body and what it can do.”

The Icewomen and others say that two minutes in the water is a good baseline — a reasonable goal for beginners. Their average tends to be about three or four minutes. But Gleason calls herself a “10-minute person.” On New Year’s Day, she went out for a solo dip — not recommended, but her girlfriend flaked at the last minute — and set up her phone to take video.

“It’s so interesting watching the video later,” Gleason says. “You can see that when I first get in, I’m gasping for air. I’m thinking to myself, ‘Why am I doing this?’ But then after about three minutes, I’m just swimming around like it’s nothing.”

January 7th, the Friday after Schmidt’s birthday swim, brings yet another snowstorm to the region, so she seizes the opportunity to invite seven Icewomen for a wintry dip in Batsto. Yes, there are other bodies of water in the Greater Philadelphia area, but the water near Batsto is said to be some of the cleanest for hundreds of miles around thanks to staunch preservation efforts and legislation to curtail development in the region surrounding Batsto.

Some of the women come from Philly. Some come from South Jersey. Schmidt invites me to tag along, and we meet at the Batsto Visitor Center. From the parking lot, it will be a mile-long hike through ice, snow and whipping winds to the secluded spot Schmidt has in mind for us. Some of the swimmers are dressed for the weather. Others emerge from their cars in nothing more than bikinis or workout shorts, sports bras and boots.

After about 20 minutes of hiking, we arrive at a swimming hole that’s covered in a sheet of ice. Rachel Oliver, 35, a tattooed mom and painting contractor who’s making the journey in bikini bottoms, kneels down to try to push her hand through the ice, which barely budges. We hike a bit farther and arrive at a large pond unencumbered by ice but surrounded by snow-covered trees.

Rachel Oliver, one of the Icewomen of South Jersey, checks ice thickness in Batsto (photo by Victor Fiorillo)

“It’s so pretty,” one of the women observes. “I’m so glad we’re doing this.” Another is disappointed that it isn’t still snowing. Hey, you can’t have everything.

Schmidt and her friends start with some warm-up exercises, to get their blood flowing and to … warm up. Then one group of four walks into the water until only their heads and necks are exposed. If, this whole time, you’ve been picturing a polar plunge, this isn’t that. And don’t call it that, because the Icewomen don’t like it. A polar plunge is when a bunch of drunk people in Wildwood run into the ocean in winter, usually for a charitable cause, and then run right back out. The whole point of what the Icewomen do is to stay in for as long as you can — something the bros in Wildwood could never handle.

Icewomen of South Jersey founder Abby Schmidt emerging from the icy water in Batsto (photo by Shira Yudkoff)

Some of the women in the first group dip their heads under; some don’t. The rest of the group continues exercising, with one monitoring a timer. She announces the two-minute mark. Then three. Around 30 seconds later, the dippers start emerging. One maxes out at close to five minutes.

The next group repeats the routine while those who’ve just emerged go back to exercising, to get their body heat back up. Then one decides she hasn’t had enough and heads back into the water. At one point, I lose track of Oliver and then find her making snow angels. In a bikini. She’s in constant direct contact with the snow for at least six minutes. (Some video of all this, below.)

Their skin uncomfortably red from exposure to the cold, the women begin to change into warm, dry clothes. Or try to. Since most report numb fingers and toes, putting on socks and shoes and pants proves to be a challenge. Some insert foot warmers in their socks, though one woman declares that’s cheating.

“Can I borrow your gloves?” Jenna Cable, 31, asks Oliver, who obliges. “My hands are not okay.”

In 10 minutes or so, everybody is dressed and feeling comfortable enough for the hike back to the parking lot. I walk alongside Adrienne Hamilton, the real estate investor from Fairmount. About two minutes into the hike, she announces that she’s forgotten one of her gloves and needs to go back to the pond. Ten seconds later, she realizes it’s been on her hand the whole time. She just can’t feel it.

On our hike back, I pose a question that’s been on my mind: “Adrienne, why don’t you just stay home in Fairmount and take a cold shower?”

“I most definitely do not have the self-control to keep that water on cold,” she says. “Besides, I’m all alone in the shower.”

I made the mistake of mentioning this Icewoman business to Deanna Cugini, a friend of my family who tries every new workout routine, wellness fad and superfood shake. Her Delco backyard happens to abut Darby Creek, which I’m pretty sure isn’t recommended for swimming. But Cugini is intrigued, so, water quality be damned, on a Sunday in late January, she insists I meet her and two friends for a dip at 3 p.m. “Be ready,” she texts me around 2:45. “The creek has a sheet of ice on top of it.”

One of the friends backs out at the last minute, explaining that he has a severe aversion to cold water. (Don’t we all?) He serves as videographer instead. The other friend, a mechanic named Joe Nelson, does show up. But she doesn’t actually expect us to go through with it. Nelson only joins in out of a sense of obligation.

“Then again, this will probably be the most fun I’ll have all month,” she remarks. “Otherwise, I’d just be lying on my couch, drinking beer and watching football.”

I don’t expect my anxiety to be so high for this adventure. What Adrienne Hamilton said about the ice water clearing her head really resonates with me; like her, I have a problem quieting my mind. But the more I contemplate plunging into icy water, the more I think there must surely be a better way. On the drive to Cugini’s backyard, the dread of what I’m about to do sets in, and I have to take long, deep breaths to calm myself down.

Sure enough, the backyard entry point to the creek is covered in ice. Cugini throws a big rock onto it, but it doesn’t go through. One of her housemates, watching from the deck, offers a heavy-duty ice chipper. Unwilling to wait, I walk out onto the ice, barefoot, wearing only swim trunks, and promptly fall through.

“Start the fucking timer!” I scream.

Cugini and Nelson are right after me.

The first 15 seconds are utterly torturous. The next 15 aren’t much better, and when our videographer announces we’re at 30 seconds, I insist it’s been at least a minute. “That’s just your mind telling you that,” he replies. (Yes, I reluctantly allowed them to take video, below.)

By the one-minute mark, I achieve some level of Zen. I’m able to do this even though Cugini is screaming and hollering like she’s on a roller coaster at Great Adventure. (“Ah, the screaming friend,” Schmidt later texts me when I tell her this. “Sometimes that’s an issue for me too with the big group.”) My mind, as Hamilton has suggested, is utterly clear for the first time since I don’t know when. But my hands and toes are in full-blown pins-and-needles mode. By the two-minute mark, I’m more than ready to get out. I can’t feel my hands and feet at all. I actually can’t move my fingers. And sensation won’t begin to return for about 10 minutes. I can still feel the effects hours later.

Cugini stays in for a full three minutes. Nelson is so quiet that at first, I don’t realize she got out right after me. While I’m doing my best to climb the treacherously steep hill to Cugini’s deck — keep in mind, I still can’t feel my feet — Nelson steps onto the bank and lights up a Marlboro Red before even drying off. It’s perhaps the most Delco thing ever.

I ask her if she’d do it again.

“Only if I had to,” she says in her Texas drawl. “Like if the police were chasing after me.” I’m on Team Nelson for this one. I’ll have to find another method of calming my mind.

As for Cugini, she says the experience gave her “absolute clarity” and insists she’ll repeat it once a week on Sundays, her only day off from work. “I feel fucking great,” she tells me. “What a great day.”

Published as “The Icewomen Cometh” in the March 2022 issue of Philadelphia magazine.