Help! My Kids Are Developing Philadelphia Accents

I lived most of my adult life away from Philly. Now that I'm back, my kids — born and raised in D.C. — are learning to speak Philadelphian. I’m not sure how I feel about that.

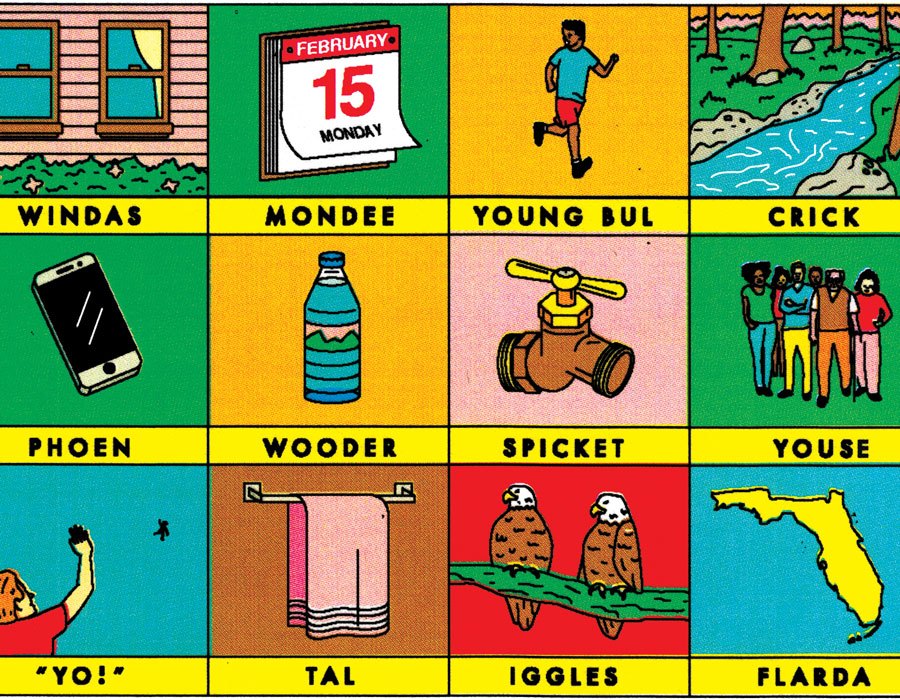

My kids are developing Philadelphia accents. I’m not sure how I feel about that. Illustration by George Wylesol

Last summer, my two small children, my late husband’s mother and I took a road trip across Utah in a 25-foot rented RV. On the morning of my firstborn’s eighth birthday, we were in Moab. He and I woke up at sunrise and stared out at the giant pink sky glowing behind massive tiered orange rocks. Small lizards and a baby rabbit scurried across the dusty gravel beneath us. Even in the early morning, I could tell it was hot and would only get hotter.

We were about as far away from Philadelphia as one could get at that moment, until suddenly, Philadelphia was all around us. “Mom,” said my kid, curled against me, still tired and sweet and not fully awake. “Do you think we’ll see any coyotes on this trip?”

Instead of saying “ki-OH-tee,” the way I pronounce it, he said “cay-YEW-dee,” the way my aunts in the Northeast might say it.

It wasn’t the only time I’d heard the glimmering of a Philly accent from my kid. Earlier that year, Joe Biden had been Joe Bite-in. Later that fall, he’d ask if for his birthday, he could get a phoen. But each time, it stopped me in my tracks. Once or twice, I suggested he say the word again with a more nondescript, newscaster-like affect. But that didn’t feel right, either. After all, why shouldn’t my newly Philadelphian son have a Philadelphia accent?

I spent most of my adult life living away from Philadelphia, so I really only fully appreciated the accent once I was gone. Even then, I couldn’t articulate it to those who asked what it sounds like. I knew wooder, of course, and was able to identify that my mom, who worked hard to smooth down her accent after fleeing Frankford for the suburbs, drops the hard consonant sounds in the middle of “vodka” (voka) and “vintage” (vinnage). Even though I couldn’t describe it, let alone perform it, I could hear that accent — at a crowded party or bar, my ears would prick after picking up some indescribable sound, and I’d gravitate to the speaker. I even felt kindly toward Ben Affleck for his little-acknowledged accent work in State of Play, where he was a Delco Congressman with a terrible secret and a half-decent patois. Hearing those sounds reminded me of home.

“We were in Philly, but it didn’t feel like I was really experiencing Philly. So why did my kid sound like Chris Matthews doing a Lee’s Hoagies commercial?”

Yet I never expected to hear them coming from my son. I wasn’t sure what to make of it. Part of the reason I found this new lyrical tic so startling was that both my kids were born and raised in Washington, D.C., where everyone has the flat accent of people who grew up somewhere else and then learned to smooth things out into generalities. When my mother came to visit, my son delighted in giving her a hard time if her accent slipped out. “It’s not wooder, Grammy!” he’d howl with laughter. “You’re saying it wrong! Say wah-ter!”

My husband grew up in the panhandle of Florida, where they put an emphasis on the first syllable of words like in-surance and um-brella. I found his way of speaking delightful and charming and wondered if my sons would pick up both his skill at playing guitar and the way he pronounced it, on occasion, git-tar.

But after my husband died, we moved to Philly — neither of which had been part of the plan. Nor was coming here in the middle of a lockdown, which meant my ability to feel connected to the city, and as if I had really come back home, was indefinitely put on hold. And in an era when it felt hard to plan longer than six months ahead, it was harder to imagine what or where our future would be.

When people asked how we liked living here, the best I could do was offer a polite smile and half-shrug. We liked being close to family. We liked our little house, and the park down the street. We liked all the glimpses we got, like climbing the rocks at Sister Cities Park or getting takeout from Chinatown or being able to drive down the Shore for a day trip. But much of what I’d imagined about living back home when I planned our move in the fall of 2019 was still out of reach. I couldn’t have big get-togethers with my high-school friends and their kids. No crowded Saturdays at the museum or sleepovers with our cousins down the Shore. We were in Philly, but it didn’t feel like I was really experiencing Philly. Instead, I was, like most people, just hanging out at home — which, for all intents and purposes, could have been anywhere from Philly to D.C. to Mars.

So why, then, did my kid sound like Chris Matthews doing a Lee’s Hoagies commercial?

Like all things pandemic-related, it came down to Zoom. The one constant in my kid’s life since we’d moved was Zoom school. Day in and day out, he listened to his second-grade teachers over Zoom, and I listened, too. They sounded like my aunts from the Northeast.

I ask Betsy Sneller, an assistant professor of linguistics at Michigan State University who has studied the Philadelphia accent as well as how children pick up on it and other regional accents, if this transmission vector makes sense. She confirms that school is where most accent work happens for young kids, though most of the research has been done on in-person school.

“What we often find is that kids sound like their parents until they go to school,” Sneller tells me. “Then all the kids come into kindergarten sounding different, and by the end of the year, they more or less sound the same.” Usually, kids pick up sounds from other students, with teachers playing less of a role. But last year wasn’t usual. “Zoom school throws a wrench in things,” Sneller says.

For most of my son’s second-grade year, there was no recess chatter, no whispering in the back of class, no spirited lunchtime discussions with other kids. Instead, outside the occasional breakout session with peers, he heard his teachers, almost exclusively.

It was Sneller’s research that resulted in a rash of news stories in 2018 that the Philly accent was dying out, which she denies — instead, her work shows how the accent is changing as it moves from generation to generation. That’s in part due to what she describes above; kids talk to one another and morph accents together, which results in a generational evolution. But since he’s not talking much to other kids, my kid may be getting a more “pure” form of the Philly accent.

Either way, the O sounds I heard so clearly in that RV in Utah are the new hallmarks of the Philly accent. These are the sounds that were prominent in Mare of Easttown and the Mare of Easttown parodies. And these are also the ones that are easiest to acquire.

Just as my son laughed at my mother for her pronunciation of water, the rest of the U.S. has mocked Philly for that particular affectation. As a result, says Sneller, the water/wooder switch is on the way out, replaced by those O/ew sounds.

“The really salient and stigmatized sounds — wooder, gay-as for ‘gas’ — are changing rapidly in part because people make fun of people for saying them,” she says. “Below the surface, there are a ton of other features connected to the Philly accent that people might not even notice.”

But whether I’ll ever hear some of those features from my son is hard to say.

At eight, Sneller says, my son is in kind of a linguistic sweet spot — malleable enough to learn some of the ways of speaking in his new home but old enough to remember how it was done where he used to live. (If my kid had been 12 when we moved, she notes, chances are he wouldn’t have picked anything up and would maintain the flat affect he acquired in D.C.) This would give him a bit of a bilingual advantage if we had moved to Spain or Japan and make it easier for him to switch between languages, but it puts him at a disadvantage when it comes to fully learning the Philadelphia accent.

Take the “ah” split, Sneller says. Most accents have a version of this — the reason Philadelphians say “gay-as” for gas but pronounce “manage” in an unremarkable way. “There are a set of really complicated rules that determine which words get pronounced like ‘ayeah’ and which get pronounced like ‘ah,’ and Philly is the most complicated version of this system,” she says. “It’s so complicated that if kids aren’t getting that input from an early age, they’re not going to get it.”

In the end, whether my son keeps the accent he has now depends on who his friends are going forward. If they have accents, he’ll keep his. If they don’t, he might not — particularly if his friends look down on a Philly accent.

“Especially in middle school and high school, kids are super-attuned to what other people implicitly disdain,” Sneller explains. “They can’t point to it, but if there’s a broad negative vibe, that might be enough for them to shy away.”

Most kids, she says, lean into their accent in the teen years, emulating those around them, then pull it back a bit in their late teens and early 20s.

That’s what happened to my husband’s Southern drawl. He didn’t even think he had an accent — it was just how everyone he knew talked — until he went to school in Chicago and was quickly informed that he sounded like a rube. So he worked to smooth out the traces of his accent, and by the time I met him, they only came out when he was angry or maybe had two drinks. I adored that accent, though, and felt sad that he saw it as something to hide.

Perhaps I need to take that more generous approach with my son. And perhaps his new way of speaking represents something hopeful.

While I’m still trying to figure out what to make of all this — our new town, our new life, our lockdown existence — my son has no such hesitation. Yes, he misses our house in D.C., but he knows this is where we live now. He misses his old friends but thrills at making new ones in the neighborhood. He’s adapting — accepting the new and adopting it as his own. He’s not waiting for things to open up; he’s not wondering if this move was the right one or if it will stick.

He’s in Philly, and he’s going to talk like a Philadelphian. Maybe it’s time I followed suit.

Published as “Wooder you Talking About” in the February 2022 issue of Philadelphia magazine.