Philadelphia Babies of the Pandemic: A Photo Essay

Sometimes, what seems like the worst possible timing turns out to be the right time. Meet seven Philly families who decided to add new members during the depths of the COVID crisis.

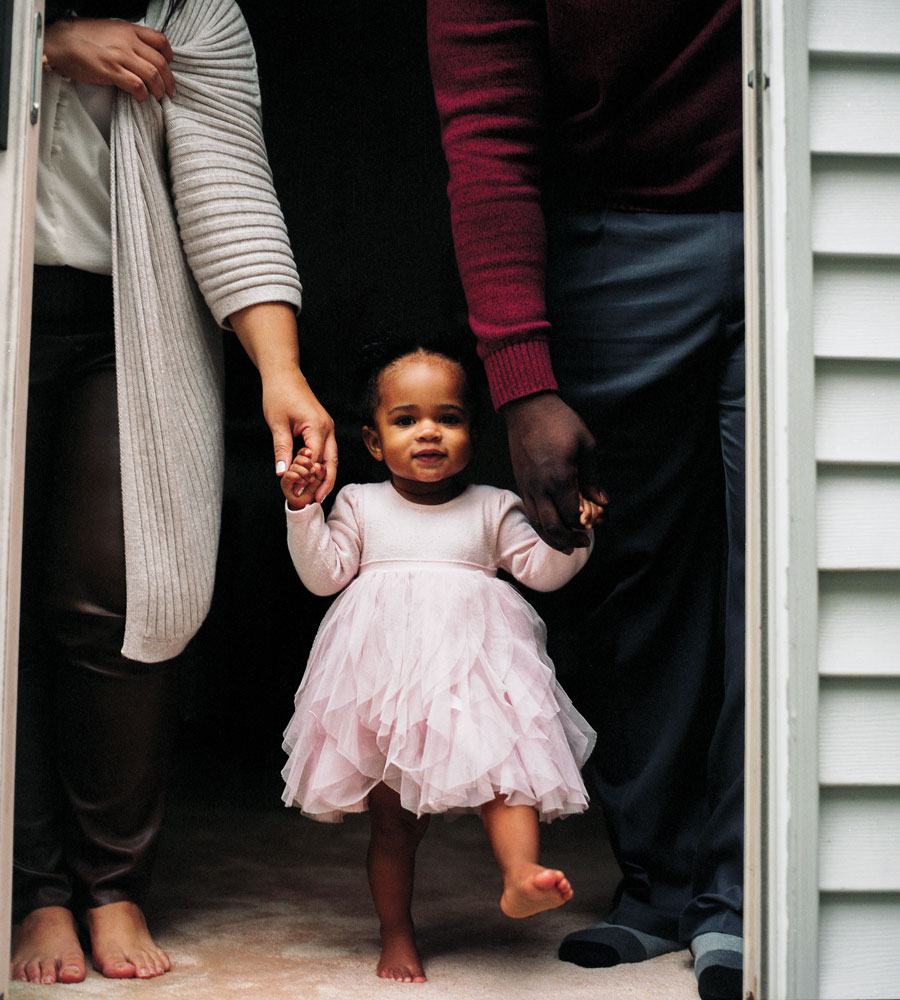

Amara Akinwande — one of Philly’s babies of the pandemic — steps out into the world. / Photograph by Jillian Guyette

In November of 2020, my daughter and her husband took my two-year-old granddaughter to Africa for three weeks to visit relatives — in the midst of a pandemic. I spent those 21 days in a blur of fear, imagining all the dreadful fates that could await them: plane crashes, Ebola, kidnappings, terrorist bombings, rogue elephant attacks. (My imagination can really get going. And I don’t travel much.) Not until they returned unscathed did Marcy inform me she was four months pregnant. She said she was afraid if she told me before they left, my anxiety would kill me. It wasn’t an unreasonable concern.

Granddaughter number two arrived safely in May. She’s gorgeous now, just like her sister, learning to laugh and roll over, experimenting with oatmeal and bananas, sometimes even sleeping through the night. I see both girls as often as I can. Watching them grow has eased the solitude and boredom of quarantine—and scares me to the depths of my soul. Every report of a school shooting, every new example of an animal’s extinction, every innocent Black man murdered by cops, every news story on refugees drowning or a meteor hurtling toward us or the evaporation of the Great Salt Lake, tips off another round of shocked horror: Who would bring a child into a world like this?

Marcy and I talk about everything, but I can’t bring myself to pose her that question. It’s such an existential rebuke, a no-confidence vote on the fate of the Earth: Are you too busy changing diapers to realize the world is about to end, whether it’s with a whimper or a bang?

And yet, I tell myself. And yet … It’s possible for personal happiness to survive global catastrophe. The human race has carried on through terrible tribulations: the Black Death, yellow fever, world wars, Hiroshima. Somewhere in the wreckage of Pompeii, some nice young couple no doubt observed the smoke and fire pouring from Mount Vesuvius, shrugged, and carried on with their foreplay. The urge for life—what Dylan Thomas called “the force that through the green fuse drives the flower”—does drive us, too. It forms the mystery at the core of our being: How do we live, knowing we must die?

The U.S. birth rate dropped by four percent in 2020—the sixth year in a row that saw births fall, so the baby paucity isn’t solely the fault of the pandemic. (Even the pope has been bitching about it.) Since their most recent peak in 2007, U.S. births are down 19 percent overall. In a Pew Research Center survey last year of Americans ages 18 to 49, a staggering 44 percent of those who weren’t parents said it was “not too likely” or “not likely at all” that they’d ever have kids—up seven percentage points since 2018.

And yet … Mark Zuckerberg can do his damnedest to seduce us all into the metaverse. Penn scientists can come up with robots that look and act increasingly lifelike. Elon Musk can be named Time’s Person of the Year for his advances (?) in technology. But it was another poet, Carl Sandburg, who wrote, back in 1948—three scant years after Hiroshima—“A baby is God’s opinion that life should go on”:

Never will a time come when the most marvelous recent invention is as marvelous as a newborn baby. The finest of our precision watches, the most super-colossal of our supercargo planes, don’t compare with a newborn baby in the number and ingenuity of coils and springs, in the flow and change of chemical solutions, in timing devices and interrelated parts that are irreplaceable.

There are as many different reasons for having babies as there are babies. Sometimes, what seems like the worst possible timing turns out to be the right time, unexpectedly. So I asked some local couples who’ve also become pandemic parents the question I still haven’t worked up the courage to ask Marcy: What on earth were you thinking?

Maybe they dreamed their child might grow up and find a solution to global hunger. Maybe they imagined this baby might someday teach the world to sing. Maybe they pictured their daughter or son mending broken hearts, or healing the sick, or perfecting nuclear fusion.

Or maybe they weren’t thinking at all. Maybe they only felt that in times as unsettled as these, a small hand curled inside yours and a downy head on your chest may be all you can hope for—may be all there is to keep you willing the world to go on.

Ebonne and Keith Leaphart, 38 and 47

Zuri Lee Leaphart, born November 21, 2021

Photograph by Jillian Guyette

After COVID squelched their big destination wedding in Jamaica, Ebonne and Keith were married in August 2020 at a friend’s Center City condo. By spring, Ebonne, the vice president of local media development for Comcast, was pregnant. “My friends were very surprised,” she says. “We had a lot going on. We didn’t expect this to happen. It was an interesting duality. This was really wonderful news in a world that felt really uncertain.”

Keith, chair of the Lenfest Foundation and founder of fintech company Philanthropi, became a dad again 15 years after the birth of son Jayden. (Another son, Jordan, is 24.) He’s also a physician, which he says wasn’t particularly helpful during the pregnancy: “With my training, I look at everything as life and death. If no one’s dying, it’s all okay. She’d be like, ‘I’m in pain,’ and I’d say, ‘Oh, you’re fine.’”

Speaking of which, at the hospital, Ebonne mentions, while she was pushing, Keith was watching an Eagles game. “Not watching. The TV was on,” he contradicts her, with a laugh. But he remembers the score when Zuri emerged: “The Eagles had 33 points. They won 40 to something.”

Ebonne proudly notes how good Jayden has been with the baby: “We’re raising some really solid humans.” Zuri, she says, has deepened her understanding of “what’s involved in juggling the demands of young children and work”—which she finds “priceless” in her managerial role.

She was astonished, she says, at how tiny he was: “I gained 53 pounds, and he was seven pounds, four ounces?” But the most extraordinary consequence of giving birth, she says, is “the immediate feeling of having your heart be outside yourself.”

Dan Kempson & Zach Altman, both 37

April & Charles Kempson-Altman, born March 26, 2021

Photograph by Jillian Guyette

Zach and Dan knew they wanted kids. “We’ve been married for 10 years,” Zach says, “and we always talked about it.” They had friends who’d gone through surrogacy. “We stole their research,” he adds, and laughs. “It was a pretty easy process.”

When the time came, they flew to Idaho. Because of COVID, only Dan could be present for the twins’ C-section birth. “They prepped me and brought me in to say hi to the surrogate,” he says. “I was getting a photo taken with her, and the doctor said, ‘You don’t want to miss this!’ I turned around, and April was already coming out.”

As half of a gay couple, Dan says, “I was nervous about Idaho. My understanding was that it’s a very red state. But everyone was incredibly kind and generous. There was not one eyebrow raised.”

They came home to Fairmount when Charlie and April were four days old—the first plane ride of what should be many. Zach is an opera singer, and Dan was one, too, before going into business as a leadership consultant. They’ve already flown with the twins to Sweden and will head for Scotland in a few months.

The couple’s friends are mostly creative types—artists and musicians. “When your professional life is unpredictable,” Dan says, “it’s hard to time having kids well. In the pandemic, you think: This is time I can devote to parenting.”

“I was prepared for it to be hard in a soul-sucking way,” Zach says. “The surprise is how lovely it is. It’s hard, but it’s not soul-crushing.”

Danielle & Tom Miller, 44 and 43

Baird Miller, born April 1, 2020

Photograph by Jillian Guyette

Danielle and Tom chose their son’s name because it means “bard” in Gaelic. “I have a background in the performing arts,” Tom explains, “and my wife’s an English teacher. Shakespeare is important to us. Storytelling is important to us.” They have quite a story to tell, having endured years of failed pregnancies and IVF treatments before turning to adoption. “When things go wrong, you sit with it,” Tom says. “Then you pick yourself up and start again.”

They went on a waiting list in September of 2018. They set up a bedroom and crib in their Ewing home. They waited. And then … “It was fast, like lightning,” Tom says. “One day no baby, and the next day, you’re elbow-deep in diapers.” A week into parenthood, Tom found out he was going to be laid off from his longtime job at Princeton’s McCarter Theater Center.

“Looking back, it was stressful: How am I going to support my family?” he says. “But the timing was perfect. I was able to stay home for the first year of our son’s life. My wife was teaching from home and was there every day.”

He’s found a new job now. Baird is flourishing. But Tom still thinks about the timing: “If he’d been born a week later, if I’d already been laid off—who knows?” If there’s one lesson he takes from what he and Danielle have been through, he says it’s this: “You try to exert control in life, but you’re not in control. You have to just let it happen.”

Alexis Apfelbaum & Jeff Levine, 35 and 40

Eleanor Levine, born July 22, 2021

Photograph by Jillian Guyette

Alexis and Jeff had a big wedding planned for July 2020, with 160 guests in the Curtis Atrium. COVID meant a backyard mini-wedding stripped down to “what we really needed to feel good,” Alexis says. “Our parents, our siblings, and lots of flowers.”

The two are both professors—she at the University of the Arts, he at Drexel—and they intended to spend their early married life adventuring. They’d booked a honeymoon in Bali. Now they found themselves holed up in their Center City apartment, both teaching via Zoom in the same room. They found a house in Bryn Mawr, and with that problem solved, Alexis says, they thought: “Why not make a baby our next adventure?”

It was weird, she says, to teach while increasingly pregnant: “On Zoom, people only see you from the neck up. On the other hand, everybody’s in your living room!”

“There are all these expectations, spoken and unspoken, about parenting,” Jeff says. “There are all these mines in the minefield. What should I do? You’re just trying to do your best.”

“People my age aren’t bringing that many children into the world,” Alexis says. “I really do think it’s imperative to continue having children even though the world is scary.” Eleanor laughs from her high chair. “We call her our little muffin,” Alexis adds.

Jeff says, “We’re teammates on Team Muffin.”

Melisa Martinez & Israel Akinwande, 35 and 32

Amara Akinwande, born October 20, 2020

Photograph by Jillian Guyette

Two days after Israel’s mom suffered a debilitating stroke, Melisa discovered she was pregnant. “I was freaking out,” she says. “My husband was dealing with so much! Do I tell him? It was a roller coaster.”

She told him. They decided to share the news with his mom even though doctors warned them it wouldn’t register. “We pulled up pictures of babies and told her,” Melisa says. “And all her vital signs started to spike.” They’re convinced she understood before she died three days later.

Israel is a registered nurse. “I thought: I can’t go to work in this situation! My wife is high-risk now!” he says. “I went to the hospital every day afraid that I’d bring something home with me.” The worst part for Melisa, a social media strategist working from their home in Collegeville, was going to doctor’s appointments without him (though he did join via Facetime): “I heard the heartbeat for the first time by myself. I was very, very angry. I felt so robbed.”

The year 2020 was “a really dark and depressing time for me,” Israel says. “My mom was buried. My dad was fighting cancer. But I had to put a brave face on for my wife.” As soon as Amara was born, though, he says, “Everything changed. She’s our shining light.”

What will they tell their daughter about the year of her birth? “I’ll tell her she saved us,” Melisa says.

Kerrin & D’Juan Lyons, both 31

Consuelo Lyons, born June 11, 2021

Photograph by Jillian Guyette

“You’d think he’s pregnant,” Kerrin says of her husband, and laughs. “He had to run out for cheesesteaks.” It’s good she can laugh, considering the couple and son Teo, then two, spent the start of the pandemic in a one-bedroom apartment. They bought a house in Germantown but couldn’t move in for months when supply-chain snafus left them without appliances. Oh, and Kerrin started a new job coordinating volunteers at WXPN the week of the shutdown. Naturally, she soon got pregnant: “We sort of thought—what about a baby? Let’s go for three good things coming out of this terrible time.”

Teo rolled with the flow, Kerrin says: “For him, it was just, ‘Mommy and Daddy are home now! Party every day!’” “We got him potty-trained during a pandemic,” adds D’Juan, who teaches Spanish at La Salle College High. “I’d tell him, ‘Go sit on the potty and try while Daddy answers emails.’” What lessons did this teacher take from COVID? “It definitely taught me what ‘wait’ means, and to be okay with the unknown.”

The couple named Consuelo for the comfort she brought them in the chaos. Kerrin likens the pandemic to her generation’s 9/11: “That was my intro into a new world. This is theirs,” she says of her kids. “We’ll walk with them, be supportive, and recognize that there’s a generational shift. It’s exciting, and it’s sobering. Like 9/11, there are going to be so many things that happen. I’m bracing myself.”

Michelle Welk & George Miller, 34 and 51

Kenzo William Miller, born August 12, 2o21

Photograph by Jillian Guyette

In December 2020, George was near the end of a three-year contract to run Temple University’s Tokyo campus. He and Michelle were living there — he’s half Japanese — and the world was locked down. “But it looked like things would improve,” Michelle says. “The vaccines had been rolled out. We never thought that wouldn’t be the end.” They’d talked about a baby; now they decided to try. “I was 50,” George says. “I thought my window for having kids was pretty much closed.” Instead, “It took immediately,” says Michelle.

George’s Japanese, he says, is “not good”; Michelle’s was almost non-existent. “I had a lot of anxiety,” she admits. Japan had closed its borders; her mom wouldn’t be able to come for the birth as planned. So George took an overdue sabbatical, and they came home to Queen Village again.

Michelle, a communications manager, acknowledges what she calls “the existential issues in the world — climate crisis, gun violence, democracy being on its last legs.”

But, she adds, Kenzo — the name represents “healthy and wise” in kanji — “has crowded those issues out of my brain. He’s forced us to stop thinking too much in the abstract. He just had his four-month checkup, and the pediatrician said we could start him on solid foods. I’m going to pick up some Gerber purees. That’s going to be the highlight of my next days.”

Published as “Betting on Babies” in the February 2022 issue of Philadelphia magazine.