What If You Could Just Take a Year Off?

Every seven years, Jews celebrate a shmita year — 12 months to rest, recharge and replenish. As we embark on 2022, could this ancient tradition be a cure for our very specifically modern malaise?

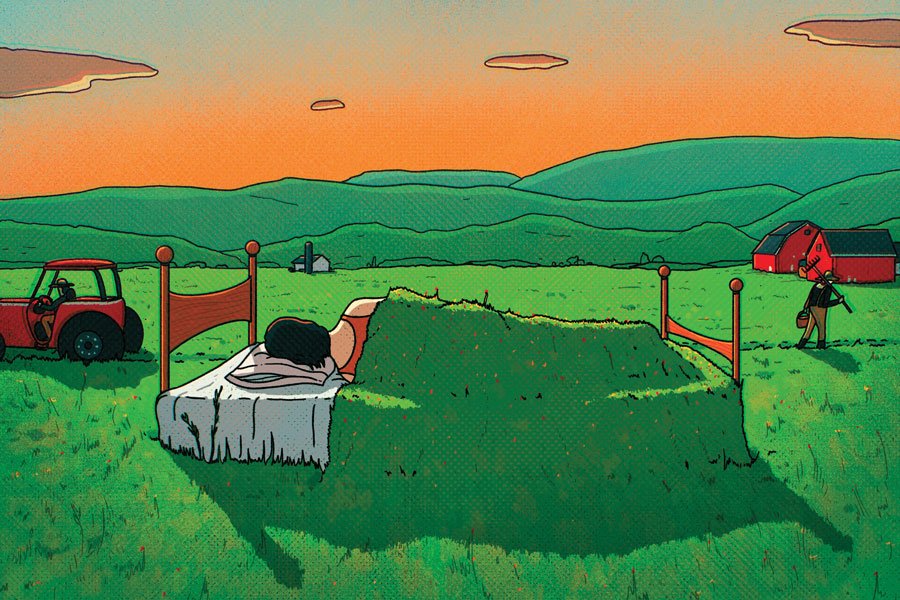

As we embark on the next phase of the pandemic, the Jewish idea of a shmita year, a year to recharge and replenish, feels particularly appealing. But is it possible? Illustration by Laurent Hrybyk

Nothing draws attention to the passage of time like doing the same thing every year, and nothing marks disruption like not being able to do it. So this past September, when for the second straight year I attended Rosh Hashanah services online rather than in person at West Philly Reconstructionist synagogue Kol Tzedek, despair again took hold.

I’ve found collaging to be one of the only practices that consistently offer me psychic relief, so there I was, sitting in my unfinished basement, gluing small slips of paper to a larger piece of paper, when I heard, through the speaker of the open laptop next to me, my rabbi talking about an idea called shmita (pronounced “shmee-ta”). The year we were entering, 5782 on the Jewish calendar, he explained, is a shmita year — lasting until next Rosh Hashanah, in September of 2022 — and those only come around once in every seven. In such a year, he said, we are called upon to release, regenerate and rest.

Jews are obsessed with marking and demarcating time — the season of this, the day of that. Each week is a seven-day cycle, split into six regular days and then Shabbat, a day of rest. But I had never heard of shmita before in my life. A whole year of Shabbat, of rest, struck me as a nice but impossible idea. I’d go broke, grow bored. Plus, we had all just endured a year of … something. Pause? Restriction, maybe? Not quite rest. We’d just finished Season 5 of The Pandemic, summer 2021, and as cases declined, I had felt, briefly, while on the sand for a jaunt down the Shore in July, free. What seemed called for now was movement, action, fight, finally pressing play again. We were so close, it seemed then, to getting back to life.

But some new disaster — economic, criminal, social, personal, ecological — always appears to be coming, each new one surprising and inevitable and not yet fully experienced when the next is upon us. Which is to say that nothing I had been looking to before that day to help me understand the pandemic — not the news, not science, not poetry or television or history — had been working. And in that context, shmita — the word, the idea, a completely different tack — began to glitter at the edges of my mind.

A quick search revealed something called the Shmita Project, an initiative that New York-based Jewish environmental organization Hazon launched in 2007 to increase awareness of the concept among contemporary Jews. “Commonly translated as the ‘Sabbatical Year,’ shmita literally means ‘release,’” the website explains. “Of biblical origin, this is the final year of a shared calendar cycle, when land is left fallow, debts are forgiven, and a host of other agricultural and economic adjustments are made to ensure the maintenance of an equitable, just, and healthy society.”

Though ancient, the concept felt so strangely and perfectly now. After all, what had the pandemic revealed but that our systems — labor, housing, health care, education — had been stretched further than they were ever meant to and were cracking? Unable to work under untenable and unsafe conditions, employees across many industries were striking. And in a move being called the Great Resignation, people were walking away from jobs, citing intense burnout. Learning about shmita felt like seeing two interlocking puzzle pieces snap into place.

“From the dawn of creation, there is a recognition in Jewish tradition that the universe is incomplete without rest,” says Rabbi Nathan Kamesar. In Genesis, “The picture was incomplete without rest.”

It’s impossible for me to think about resting for a year without thinking about the novel My Year of Rest and Relaxation, by Ottessa Moshfegh. In it, a young white woman, broken by an amorphous loss, decides to temporarily check out of life. She concocts a system of pills, alcohol, television and deli coffee that allows her to be either asleep or in a state of complete, numb relaxation for an entire year.

To me, the main character’s quest seemed plainly unorthodox but not altogether unappealing or illogical. When I think about rest in my own life, I tend to think about it in this way: the absence of something, a respite from all that feels effortful, complex, taxing.

It was with this definition of rest in mind that I began to explore shmita. But it wasn’t long before I realized I was going to need an entirely new framework.

It turns out that shmita shows up three times in our holiest books. In Exodus and Leviticus, shmita is all about farming — letting fields lie fallow so they can regenerate and continue to be fertile. But it’s in Deuteronomy that the concept really gets its teeth. Recognizing that the holding of debts is an essential means by which the rich stay rich and the poor stay poor, the author[s] dictate that every seven years, all debts must be forgiven. As the fields lie untended, whoever is hungry — human or animal — is invited to come eat from them. With the extra space that comes with not working, people are asked to recharge and reflect, making shmita an economic, social and spiritual practice.

Rest, in this way of thinking, isn’t doing nothing, but rather doing something essential. I decided to explore this idea with some of Philadelphia’s experts on Jewish thought and was fascinated by what I learned.

“From the dawn of creation, there is a recognition in Jewish tradition that the universe — both in the global sense of the cosmos, and in the individual sense of the universes of our lives — is incomplete without rest,” Rabbi Nathan Kamesar, of the Society Hill Synagogue, where services are based on the Conservative liturgy, wrote to me. “‘On the seventh day, God finished the work that God had been doing’ (Genesis 2:2). The work wasn’t finished until the seventh day. The picture was incomplete without rest.”

A teaching from a fellow Kol Tzedek member, Miriam Stewart, builds on this idea. She points out that the words the Torah uses to describe what God did on the seventh day are “rest,” yes, but also “was re-ensouled.” “These last words,” Stewart writes, “shavat vayinafash … share a root with the words used to describe the way God breathed life into Adam and Eve. So it seems that God himself is being breathed into life through rest.”

This all seemed basically correct, if a bit abstract, but the following anecdote from Danielle Selber, matchmaker at Tribe 12, which connects Philadelphians in their 20s and 30s to Jewish life, helps me really get my hands around the idea.

“Years ago, my friend Michal created a challah-baking workshop that included a yoga session during the 45 minutes it took the dough to rise,” Selber writes to me. “She liked to say, ‘Rest is in the recipe,’ and that has stuck with me. You can’t skip the step where you let the challah rest, just like you can’t harvest from exhausted land.”

But how, then, to practice this in everyday life? According to the rabbis and other spiritual leaders I spoke to, difficulty achieving shmita is as old as the idea itself. It’s been practiced at various points in history, its intention has been at odds with its implementation, and its goals have often been elusive.

My own rabbi, Ari Lev Fornari, describes shmita as “aspirational” for Jewish people. Rabbi Adam Zeff, of the Germantown Jewish Centre, adds, “We don’t have any evidence that shmita was ever practiced as it was intended in the land of Israel,” explaining that the mandate to release debts during shmita years caused problems when lenders became unwilling to make loans to farmers because they knew that come shmita, those loans wouldn’t be repaid.

“The Torah says that if we forgo shmita, ‘The land is going to vomit you out,’” says Rabbi Adam Zeff. “This resonates as I feel on an almost daily basis as if I’ve been vomited out.”

The concept went through a long period of irrelevance until the rise of Zionism in the late 19th century, when Jews of all provenances and professions began moving to Israel en masse to go “back to the land” and shmita experienced a brief resurgence. “Not always to the letter of what it says in the Torah,” says Rabbi Zeff, “but people did observe it, and there was acknowledgement that the land needs to rest.”

But in recent decades, starting in the 1960s, the Jewish environmental movement has connected the idea of shmita to climate crisis, reinvigorating it for a new era — and just in time for the pandemic.

Rabbi Fornari says he first learned about shmita from Hazon during the last cycle, from 2014 to 2015. For him, shmita isn’t primarily about rest, but rather about release — release from oppressive economic systems and a reorientation of our focus from the individual to the collective. These are both ideas much in the current conversation on everything from economic inequality to vaccination.

Just because shmita has never been fully realized in real life doesn’t mean it’s not something to aspire to. Beyond aspiration, Rabbi Zeff says, shmita is indeed essential, and bad things happen if you don’t practice it: “The Torah says that if we forgo shmita, ‘The land is going to vomit you out.’ If you don’t let the land rest, the land will take its revenge on you.”

This resonates, as I feel on an almost daily basis as if I’ve been vomited out. I’m besieged by disease, death, white supremacy, wildfires, the loss of freedoms and parts of Planet Earth previously believed to be forever. Also, by the dishes, the family, the work, the boss, the false alarms and the positive test results, the pets and their poop, the deadlines met and missed. The trying and failing to move forward toward sacred dreams while everything is on fire. The inability to rise from the couch. I am, you are, we are … so tired.

It’s occurred to me more than once over the past two years that all this has been foretold and preordained — that the pandemic and climate change and the murder of Americans by agents of the state is all happening because we failed to do something. But until I learned about shmita, I had no words to articulate the precise nature of this failure.

“I feel confident,” says Rabbi Fornari, “that if the world had observed shmita, we wouldn’t be where we are.”

“Personally,” writes Rabbi Elyssa Cherney, founder and CEO of the Philly-based organization Tackling Torah, “I think [shmita] is more about taking that step back to ask the big questions of ourselves and our work that allow us to find deeper meaning in our contribution to the world. For me, shmita symbolizes the step back.”

The pandemic, most everyone I spoke to agrees, has functioned as a kind of mandatory step back, a nonconsensual shmita.

“We were forced to let go of our normal ways of living and adopt a completely different way of living,” says Rabbi Zeff. “What is the economic system in which I’m laboring? Is this really what I should be doing? The pandemic has made people rethink a lot of things. I think the shmita year is intended to get us to rethink.”

This shmita, Rabbi Fornari says, he’s following a personal practice of limiting the external teaching and speaking obligations that usually supplement his income from Kol Tzedek, to create more space in his life for rest and regeneration. Kol Tzedek as a congregation is focusing the year on debt abolition, having already raised almost $50,000, which, amazingly, abolishes about $4,000,000 to $5,000,000 in medical debt for Philadelphia patients experiencing financial hardship. (Hospitals often sell debt they can’t collect at a discount.)

Danielle Selber of Tribe 12 says she’ll skip planting herbs in her patio garden as a symbolic gesture and will shift her family’s charitable giving into micro-lending platforms, mutual aid funds, and policy initiatives that work toward universal basic income: “Giving someone cash, lending without interest, or relieving a debt are consistently three of the very best ways to change someone’s situation permanently.”

As I write this, there are exactly 300 days left in this shmita year. (There will be fewer when you read it.) “Relish it!” proclaims the Shmita Project website, and I plan to try.

Shmita’s rest and release aren’t Moshfegh’s. Rest isn’t alcohol. Rest isn’t pills or coffee or TV or sleep. Rest isn’t oblivion. Rest is, maybe, attunement, awareness, aliveness; the presence of something special.

I’m nearly done with my shmita lesson when I learn that in Jewish lore, for the duration of Shabbat, each Jew receives a Neshama yetera, or a second, additional soul. This soul is only temporary; it comes when the sun goes down on Friday and leaves again when the sun goes down on Saturday. This second soul brings with it “an expanded heart,” a special focusing power of the mind, and a higher level of wisdom that enable us to understand mysteries we might otherwise find incomprehensible.

In the weeks after Rosh Hashanah, I keep working on the collage I’ve started, and slowly, the pieces of paper take the shape of words — and the words are: We can’t go back. The truth has been revealed, and the truth is that how we live now will never stop, and will never end. This is no bounded period, demarcated on a historical timeline, but a new thread of something — what? — that must be braided into the future.

Through a combination of long-range financial planning on the part of my past self and inertia on the part of my present self, I find that I’m in a position to be able to go a whole semester this spring without teaching, to focus on the novel I owe my publisher. I don’t know what this book will be, and I have a hunch that what I’ve got so far may not last — that something very different is required of me. After this investigation, I tend to see shmita as a whole year in which we have something additional — a second soul, perhaps. Some magical power to conjure vitality, to conjure insight, and to conjure justice — a chance that might not come again for a long time. I plan to use the days I have left looking for it.

Emma Copley Eisenberg is the author of the New York Times notable book The Third Rainbow Girl: The Long Life of a Double Murder in Appalachia and two forthcoming books of fiction. She lives in West Philadelphia and directs Blue Stoop, a hub for literary arts.

Published as “Pressing Pause” in the January 2022 issue of Philadelphia magazine.