The Pandemic Exposed Our Broken Higher-Education System. It’s Also Given Us a Chance to Make Things Better

The chaos of COVID could mean the start of a new era in saner, fairer college admissions. Sometimes it takes a revolution to build a better world.

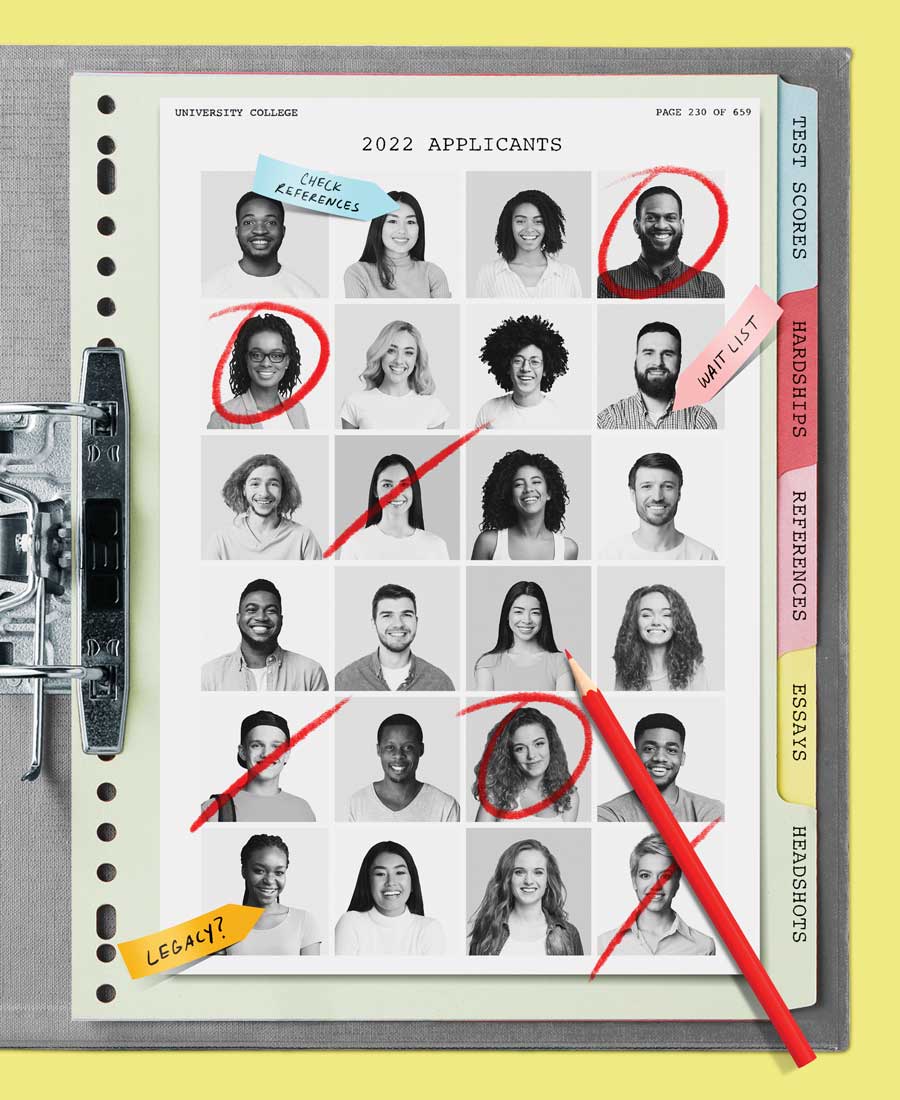

COVID-19 exposed just how badly broken our higher-education and college admissions system has become. Photo-illustration by Matt Chase

All it took to blow up the American system of higher education was a deadly pandemic.

For years, admission to elite colleges and universities has depended on a, well, dependable set of factors. As ranked in a survey of admissions employees in 2019 — pre-pandemic — those were grades, curriculum strength, standardized test scores, and the admissions essay. So what happens when quarantine forces cancellation of those all-important tests? When high-schoolers are learning remotely, or in some mash-up of in-person and online, isolated and anxious? When stretched-thin guidance counselors have to reach out to students via Zoom? When kids can’t schedule college-campus visits? When the carefree self-exploration celebrated in the admissions essay grinds to a halt?

In the absence of the quantifiable factors they traditionally relied on — comparable GPAs and test scores — colleges are struggling to figure out how to choose whom to admit and whom to reject. And that’s not all they’re dealing with. A perfect storm of contributing factors over recent years — COVID, a plummeting American birth rate, the shocking revelations of the Operation Varsity Blues admissions scandal, economic unrest, the movement for social justice — has walloped higher ed with a series of body blows.

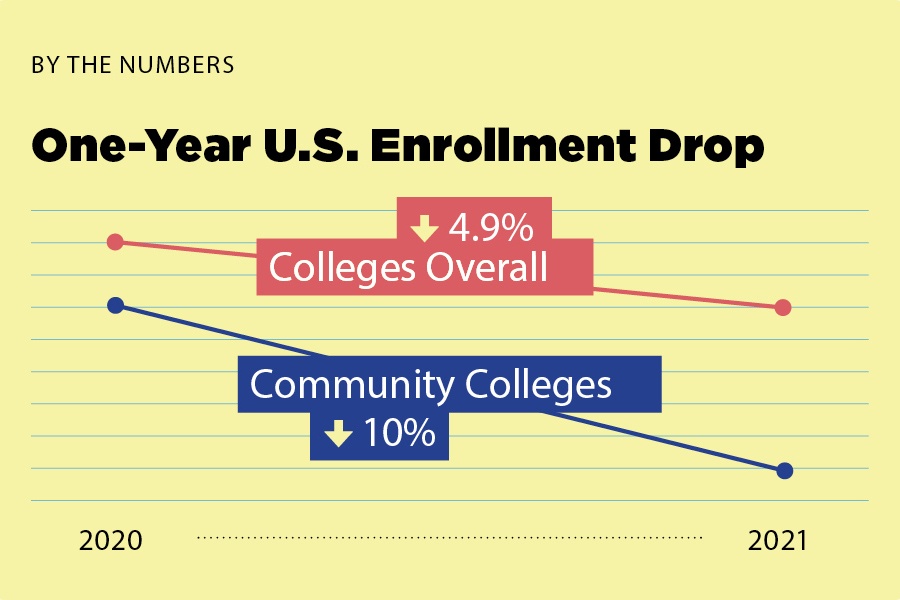

Overall, U.S. colleges saw undergraduate enrollment for spring 2021 drop by 4.9 percent over spring 2020. That’s a decline of 727,000 students. The Pennsylvania figures are equally gloomy; enrollment for spring 2021 was down for the third straight year, by a total of almost 50,000 students over 2019. That’s 50,000 kids with their dreams deferred, their futures on hold.

The fewer kids enrolling and paying tuition, the fewer dollars colleges have to get by on. Dozens of schools nationwide, including some that have been around more than a hundred years, are closing or consolidating due to financial woes — among them, six Pennsylvania state universities that are folding down into two. In the first year of the pandemic, higher ed lost more than 650,000 jobs. Professors who can’t find room on the tenure track because of budget cuts are walking away from academia; others are grappling with the challenges of teaching online or are fighting to unionize to protect themselves. Colleges are gutting humanities programs to make way for more practical subjects like computer science; in March, Cabrini University in Radnor announced it would nix majors in religious studies, Black studies and philosophy. Mega-universities like Arizona State and Southern New Hampshire, with their massive enrollments, have been eating into the diminishing pool of college candidates. And then there’s student debt. The average U.S. household that carries any owes more than $57,500. No wonder. The cost of tuition plus fees at nationally ranked schools has more than doubled over the past two decades.

COVID provided the impetus for change, says Shawn Abbott, Temple’s vice provost for admissions: “For us, it was a revolution.”

All these factors have made an already fraught process for parents and kids even more daunting. The old way of doing college admissions may have sucked, but at least it sucked in ways we understood. We were used to it. Kids adapted to it; when the trend was for well-rounded applicants, they went out for sports, took part in school plays, joined student government. When that flipped to a preference for specialists, they hunkered down and stuck to concert piano or tae kwon do. They always took those standardized tests — sometimes many times over, and often with the aid of pricey test-taking prep. Now, in the wake of COVID’s tumult, schools and parents and kids are all left to wonder: Where do we go from here?

“This has been the most difficult year of my career,” says Shawn Abbott, Temple University’s vice provost for admissions, financial aid, and enrollment management. “It’s been a disaster.” And yet … “It’s also been the most exhilarating year of my career.” COVID provided the impetus for a sea change, he says, in how Temple did things: “We overhauled an admissions process that had been tweaked at the edges but hadn’t undergone significant change in decades. For us, it was a revolution.”

He’s not alone in his assessment that the chaos of COVID could mean the start of a new era in saner, fairer college admissions. Sometimes it takes a revolution to build a better world.

My dad grew up in Cheltenham, the sixth of seven kids born to a housewife and a man who sold windows door-to-door during the Great Depression. Dad joined the Army at age 17 to fight in World War II, served overseas, came home, and went to Temple on the GI Bill — the first in his family to matriculate. My mom, the daughter of Lithuanian immigrants living in South Philly — her dad was a shoemaker; her mom worked in a cigar factory — also went to Temple, which is where she met Dad. Their kids would go on to Princeton, Penn, Harvard, Cornell and Duke. That was the way the world worked back then.

What got my siblings and me into those schools were our standardized test scores — not exactly surprising, considering our parents were both teachers. The Scholastic Aptitude Test, better known as the SAT, got its start early in the 20th century as an IQ exam for Army recruits before morphing into a means of assessing college candidates who hadn’t attended ritzy East Coast boarding schools and thus were of dubious provenance. Its history aligns neatly with my family’s experience of “meritocracy.” Of course, we were middle-class and white.

The test has been fiddled with over the decades, but along with its rival, the ACT, it became the backbone of college admissions — at least, until COVID wreaked havoc on the process. One after another, hundreds of colleges and universities announced they wouldn’t be requiring standardized test scores from applicants, as quarantine hampered test administration and general societal upheaval threatened students’ ability to concentrate on vocab words and algebra. For the fall 2021 admissions cycle, only 44 percent of Common Application filers included SAT or ACT scores, down from 77 percent the year before.

Photo-illustration by Matt Chase

Even prior to COVID, the public had grown leery of the tests, as research increasingly showed they favor kids from families like mine and discriminate against candidates of color and those from low-income backgrounds (as do the PSAT and AP tests). A newfangled SAT essay-writing section, introduced in 2005 to help colleges see beyond the numbers, made nobody happy and was finally scrapped this year. But the pandemic really upended the standardized-test world by making the tests nearly impossible to administer and, thus, require.

The resultant lack of test scores is what Shawn Abbott cites as the impetus for Temple’s admissions team to consider applicants in a different way. “In the absence of the SAT, we had to look at other components and data,” he explains. “What should we reward instead of those scores when it came to admissions and financial aid? Are you the first in your family to apply to college? Do you come from a historically impoverished neighborhood? How rigorous was your high-school curriculum?” As such considerations assumed new importance, Temple’s suddenly homebound admissions officers, with the help of Zoom, could offer one-on-one information sessions to students who might not have been able to meet with them in person.

The result was a Temple Class of 2025 that’s 45 percent students of color, including a 24.5 percent jump in Black students over the prior year. Thirty percent are first-generation students, while 33 percent come from out of state — Temple’s highest rate ever. “And there’s been no change in our academic profile,” Abbott says. “It’s essentially the same. One hundred and one percent, we will keep on using this method. Sure, relying on scores is easier. But this brought a kind of clarity.”

West Chester University was also among the institutions making test scores optional for 2020 and 2021, says Christopher M. Fiorentino, who’s been president of the school — like Temple, part of the state’s higher-ed system — since 2016. As a result of that shift, a full quarter of WCU’s undergrad applicants were eligible for federal Pell grants, which go to low-income families. “We became more competitive,” Fiorentino says. “We wanted to encourage candidates who might feel they’re not qualified.” The havoc of the pandemic resulted in a real-time experiment in improving access — one that seems to have worked, and not just for West Chester. A number of schools across the nation, including the entire, massive California state university system, have announced they won’t look at standardized test scores in admissions decisions going forward.

For the topmost tier of colleges, though — what are known as the Ivy Plus schools, which include the eight Ivies, Stanford, MIT, Duke, and the University of Chicago — test-optional admission doesn’t make as much difference as you might think, says Aviva Legatt, founder of Ivy Insight, a consulting firm for undergrad college applicants that’s based on the Main Line, and author of the new book Get Real and Get In: How to Get Into the College of Your Dreams by Being Your Authentic Self. “It does increase applications from underrepresented kids,” she acknowledges. “But for general students, it’s misleading. What does ‘optional’ even mean?” For this fall’s class, for example, Penn accepted about 15 percent of its early-decision applicants. Two-thirds of those applicants submitted test scores; three-quarters of the admitted kids did. “So are they really ‘optional’?” Legatt asks.

“A lot of elite institutions encourage lots of people to apply, accept a small number, and keep their acceptance rates low for prestige,” says Chris Fiorentino, president of West Chester University.

Legatt, who worked in admissions at Wharton before founding her company, explains that when the most competitive colleges made test scores optional, “More applicants figured, ‘They’re not going to look at this 1300. I can do it,’ where they would have disqualified themselves in previous years.” (Harvard’s early-decision applications spiked by 57 percent.) For top-tier colleges, that’s a feature, not a bug. “A lot of elite institutions encourage lots of people to apply, accept a small number, and keep their acceptance rate low for prestige,” Fiorentino says. Test-optional policies pushed Ivy League acceptance rates to historic lows, which only makes the schools seem more elusive and exclusive, which only makes more families want in.

Legatt noticed another effect of the test-free policies: “Kids were applying to more colleges,” she says — as many as 25 or 30 instead of her recommended eight to 10. While that might seem like merely hedging one’s bets, in college admissions, it’s never that simple. Admissions officers all have horror tales of students who refer to their love for the wrong school in their earnest application essays, or who detail their fervent interest in a major that isn’t offered. Even if you proofread diligently, “It’s hard to demonstrate a real interest,” Legatt notes, “if you apply to that many schools.” And more than anything, she adds, schools are looking for students who genuinely want to be there — because they care, kinda, sure, but also for business reasons: Such kids are more likely to enroll and thus increase the “yield rate,” providing reliable deposits and full classes and aiding long-term planning.

One more by-product of the standardized-test moratoriums, Legatt says, was an increase in emphasis this year and last on that admissions essay — you know, where kids talk about the nonprofit they founded to collect old prom dresses, or the trip to Haiti to work with impoverished children, or the hike along the Appalachian Trail where they discovered yes, yes, they could poop in a hole. Alas, not all kids have the leisure or the funding for such self-discovery. And even for those who did, quarantine curtailed such adventures.

No great loss, says Temple’s Shawn Abbott, who considers the essay “arguably the most manipulated piece of the process. I’m one of the people who are increasingly suspicious of the role it should play.” Some families have access to consultants who can guide and edit or even ghost-write; some don’t. A new study out of Stanford this year found essay content even more strongly tied to applicants’ socioeconomic status than standardized test scores.

College admissions reps, Legatt says, get pretty good at sniffing out the phonies and the overly coached when it comes to the essay. She cites what she calls the Impressiveness Paradox: The harder applicants try to impress, the more skeptical admissions staffs become. “If kids are just checking the boxes and aren’t passionate about what they want to do, when they’re just going through the motions, you can tell.” She suggests that kids take the time to tailor their essays to a particular school, cut the fluff, and be straightforward rather than wordy and clever. Art Sharon, a resident of Philly’s Francisville neighborhood who taught high-school and college essay-writing for four decades (and graded AP English Comp essays for many years), always told students to heed the father’s advice to his would-be-writer son in A River Runs Through It: “Half as long.”

One impetus for that advice, to be brutally frank, is that most 18-year-olds aren’t all that interesting — yet. “One of my big takeaways at Penn,” says Legatt, “is that the essay was often boring or not helpful to the applicant.” (Sharon, who’s retired, says, “I would still be teaching — I love teaching — if they would let me teach without grading another damn essay.”) And though it may seem that underprivileged kids would have a leg up here, with more compelling tales to tell of overcoming adversity, there’s a certain moral squeamishness to mining your misfortune for the sake of a college education. In May, the New York Times ran a poignant essay by Elijah Megginson, a Black high-school graduating senior from Brooklyn, on how writing his essay about his life’s many, and genuine, challenges made him feel like he was “trying to gain pity”: “It was my authentic experience, but I felt that trauma overwhelmed my drafts. I didn’t want to be a victim anymore. I didn’t want to promote that narrative. I wanted college to be a new beginning for me.”

At Collegeville’s Ursinus College, where test scores have been optional for more than a decade, “We thought deeply about how to serve our audiences by asking ourselves, ‘What do they need and how can we meet them where they are’” in the face of COVID, says director of admission Diane Greenwood. More than 60 percent of professors at the small liberal arts college stepped up, calling, texting and Zooming with prospective students to answer questions about majors, departments and student life. Scott Deacle, an associate professor of business and economics, says, “Students and their families must sacrifice a lot for a college education, so it makes sense to give them a name and a face to associate with an institution.” This and other efforts, including virtual events, paid off with a bigger and more diverse Class of 2025.

Shawn Abbott thinks that post-COVID, the general trends toward digging deeper into applicants’ backgrounds, widespread interviewing (now that we’re all adept at Zoom), less reliance on scores, and increased skepticism regarding essays will help kids (and parents) feel less compelled to embellish their experiences — and maybe even fret less about their applications. For now, though? “They’re just as anxious and sweaty about the process as ever,” he tells me. “They’re worried about the future. We have to get out there and share the good news, the gospel. The anxiety isn’t going away anytime soon.”

Not everyone, alas, is on board with ditching the numbers for a more holistic approach. In a recent article in the Chronicle of Higher Education, writer Matt Feeney opined that the pursuit of so-called “authenticity” has only put the system more out of whack, rewarding not authenticity itself but the “authenticity effect — cultured parents, costly admissions coaches, able and informed college counselors.” His solution? Lotteries, an idea that’s been repeatedly proposed down through the years, based on the notion that because elite schools have so many nearly indistinguishable applicants, the process already amounts to a crapshoot. Not long after Feeney’s piece ran, the Chronicle published a counter-argument by Rebecca Zwick noting that the random allocation of valuable goods like an elite education goes against human nature, as illustrated by the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, whose lottery in the 1970s provoked so much agitation that the school reneged and admitted all the applicants involved.

Feeney has also argued, in the New Yorker, that holistic admission is even harder on kids than cut-and-dried test scores, because now, it’s not your numbers that are being rejected; it’s you. “What ‘holistic admissions’ means is that colleges give a boost to the applicants they like more, as people,” he writes — a tough assessment for a tender teenage psyche to handle.

Aviva Legatt says she’s found that while kids may understand intellectually that elite admission “is a roll of the dice,” emotionally, any rejection is still a big blow: “It’s very easy to take the process personally.”

Of course, the kids are only setting themselves up for that blow by focusing so tightly on the handful of U.S. colleges that work to pump up their application pools and keep admittance figures down, instead of the vastly greater number whose acceptance rates top 75 percent. (Fewer than five percent of four-year U.S. colleges admit less than 30 percent of applicants; the average is between 50 and 70 percent, the category into which Penn State, Virginia Tech, James Madison, Miami, Rutgers, Pitt and Purdue all fall.) This makes Temple’s Shawn Abbott slightly crazy. “As long as the country — and the world, really — has this perverted obsession with colleges and universities that have brand-name recognition,” he says, “the demand will always outstrip the supply, and hearts will be broken come April.”

No matter how much families may want to, you can’t shoehorn 400,000 applicants into 17,000 Ivy League seats.

In the year 1940, Harvard University accepted 85 percent of all its applicants. In 1970, it gave the nod to 20 percent. For the Class of 2025, applications were up 43 percent year over year; there were 57,435 wannabes. Only 3.43 percent of those got in. Whom do you like best, Ivy League?

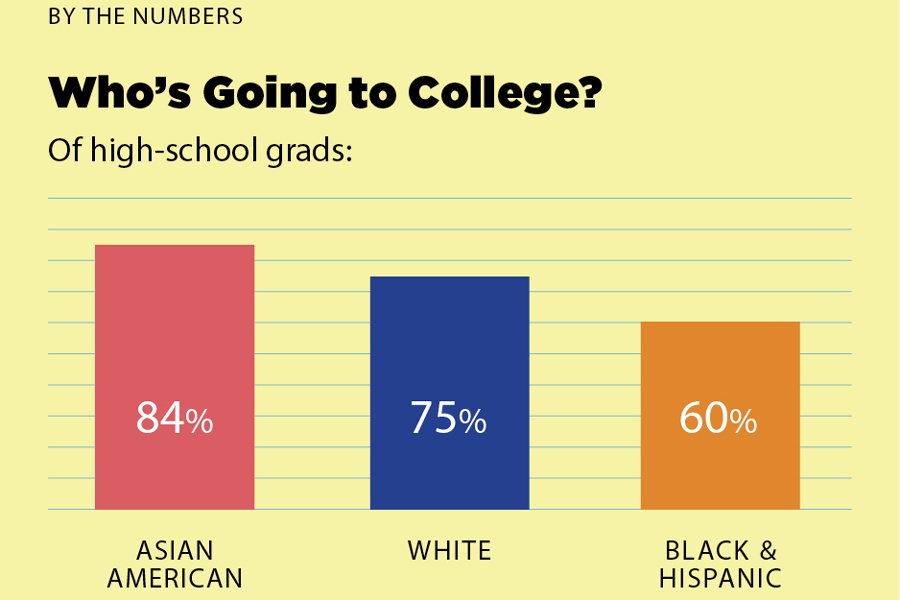

Despite upper-echelon colleges’ pledges to diversify racially and economically, their answer to that question is often: kids with the most money. According to a study by Opportunity Insights, a nonprofit headquartered at — gulp — Harvard, from 1999 through 2013, Ivy Plus colleges had more students from families in the top one percent of income distribution than from the entire bottom half.

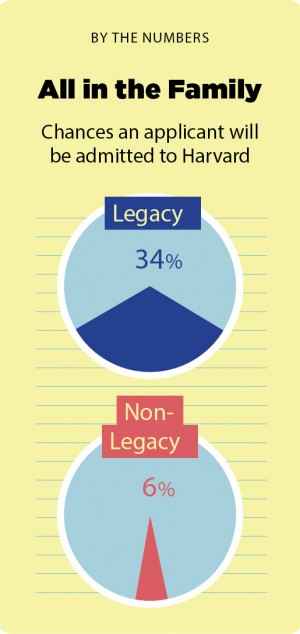

The thing about money is that it perpetuates itself, and nowhere is that truer than in college admissions. Colleges argue that so-called “legacy applicants” — those with relatives who attended a school — help build endowments and ensure financial solvency. According to Forbes, such applicants to Harvard are six times more likely to snag a letter of acceptance than those without connections. A shocking 36 percent of the school’s Class of 2022 was made up of legacies, a hefty leap from 29 percent the year before.

Policy analyst James S. Murphy argues that the real scapegoat for higher ed’s economic divide is private high schools, which can cost just as much as college. (The tab for boarding students at the Hill School in Pottstown, alma mater of Donald Trump’s oldest two sons, is almost $64,000 a year.) While 12 percent of Harvard’s Class of 2018 admittees were legacies and another 10 percent were recruited athletes, Murphy writes in Slate, nearly 40 percent attended private high schools. Per the Census Bureau, only seven percent of all American kids do — but private-school grads make up a third to half of students at the nation’s most prestigious colleges. And private-school enrollment is growing, not contracting; by 2025, it’s predicted to have risen by 13 percent over 2017. Locally, Swarthmore College announced in 2020 that it was putting an end to the opaque yet widespread practice of “counselor calls,” in which high-school guidance counselors advocate one-on-one for admission for their students, after it discovered that 90 percent of those calls came from private schools.

A team of economists has proposed one novel way to even out the scales and give less advantaged college applicants a leg up: Keep standardized test scores, but tack on extra points for middle-class and poor kids. A 160-point bump, they argue — the boost colleges typically provide to legacy applicants — would grow the number of low-income students at Ivy Plus schools from the current four percent to 12 percent.

But the proposal, while alluringly simple on its face, runs into all sorts of complications upon further examination: Who should lose the seats these lower-income students gain? How would this affect colleges’ efforts to bolster racial diversity? How could poor kids afford such schools — by taking out more student loans? It also flies in the face of the trend toward holistic admissions.

Photo-illustrations by Matt Chase

Legatt, for one, argues that what could genuinely fix the admissions process is for schools to simply be up-front about what they need. “Make it easier for kids to match themselves to a college’s priorities,” she suggests. “Have institutions make the criteria public every August, to every applicant. Does the crew team have 10 open seats this year but only two for next year? Does the marching band have an opening for a tuba player? Are you looking to increase your demographic diversity and have students from all 50 states? Did you just get a big donation for a new biotech center and need kids interested in enrolling in it, to gratify the donor? I’m a big fan of transparency.” Unfortunately, she adds, “Schools like to project that air of mystery.”

For now, even as schools try to adjust in a post-COVID world, the cards would seem to be stacked against kids from families like the one I grew up in — working- or middle-class public-school kids who see college as an escalator up in the world, rather than a way to cement their already lofty status. And they are, to a point. But here’s the catch: It would be one thing if being a legacy or a top athlete or a prep-school grad really did indicate greater potential in the qualities a college is supposed to prize: critical thinking, reasoning ability, creativity, problem-solving, yada yada yada. But Murphy notes that historically, at Harvard, private-school grads have underperformed compared to their public-school peers. What’s more, according to Opportunity Insights research, the colleges and universities whose students show the greatest upward social mobility aren’t Ivy Plus institutions at all; they’re “mid-tier public schools that have many low-income students and very good outcomes” — including the University of Texas at El Paso, Glendale Community College in California, SUNY Stony Brook, and Cal State at L.A., which ranks number one.

Now that the worst of the pandemic appears to have ebbed and we’re moving back toward a sort of new normal, there’s an increased urgency to getting kids who’ve given up on college back into the pipeline, for the sake of the schools’ economic futures and those of the kids. In an essay in the New York Times, Thomas B. Edsall noted that while growth in earnings for each additional year of K-12 schooling has been flat in America since 1980, the earnings increment for a bachelor’s degree rose from 30.4 percent 40 years ago to 56.4 percent in 2017. Yet nearly half of kids who opt out of college say they do so out of fear of student debt, which is borne by Black and older students disproportionately. In a Niche survey this year, 93 percent of college students said they have financial concerns, and 53 percent of parents said the COVID crisis has left them less able to contribute to their kids’ college educations.

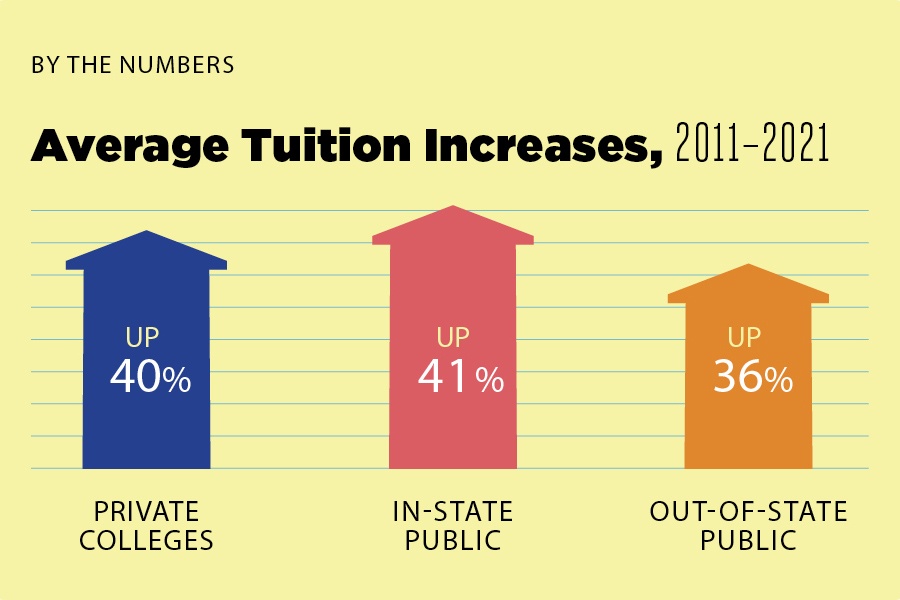

Fifty years ago, federal Pell grants covered almost 80 percent of the cost at a four-year school; today, it’s less than 30 percent. Shawn Abbott says that in the 1960s and ’70s, lower-income students could cobble together a way to pay for college: those Pell grants, state grants, some contribution from family, a part-time job for 10 hours a week. It’s how my parents put us all through school. “That’s not viable anymore,” Abbott says flatly. “There are no federal or state funding sources.” So students simply run up debt. And while there’s been plenty of talk about student loan forgiveness, any widespread effort on that front will likely run into the same legislative opposition that’s seen state funding for higher ed decline in recent years. From 2008 to 2019, Pennsylvania’s funding dropped by 33.4 percent. Meantime, tuition rose by 20.3 percent at the state’s four-year public colleges — and 41.3 percent at community colleges.

You can see why for some students and families, there’s real hope in the Biden administration’s proposed American Families Plan, which would make community colleges free to all comers. But even this apparent salvation presents issues: Abbott worries that it could disincentivize viable candidates for Temple or Penn or Swarthmore from applying to four-year schools. And educator Eric Wolf Welch recently argued in the Washington Post that the plan would only intensify America’s socioeconomic divide: “Low-income students will be relegated to attend community colleges, while more affluent families will send their children directly to four-year colleges.”

With so much sturm und drang in academia, Abbott says that when friends with kids ask his advice about colleges these days, he finds himself urging them to consider a whole new set of criteria when deciding where to apply: “Look at a school’s financial health. Investigate the bond rating, the amount of debt, the endowment, how tuition-dependent it is.” Most families, he says, never take such factors into consideration. It’s hard, when your kid has her heart set on a certain golden-hued campus, to tell her it’s on shaky financial footing. But he’s convinced it’s become necessary.

He’s also concerned that forgiving loan debt will just encourage more debt for some students. “We’re already seeing it with kids,” he says. “They’re less worried about borrowing because they suspect it will be forgiven. It’s a sort of naive hopefulness, I guess.”

Meantime, the clock is ticking down to January 31st, when the pandemic-inspired interest-free deferments for federal student loans run out — and the temporary breathing space they gave some 42 million borrowers is due to squeeze shut for good.

Given the widespread attention the social justice movement has garnered since the murder of George Floyd, demands that colleges address the inequities in admissions aren’t going away. In the Chronicle of Higher Ed, writer Tom Bartlett declared 2021 “a watershed moment in the history of higher education and race.” Enrollment at historically Black colleges and universities, or HBCUs, is up 20 percent in states that have seen rises in hate crimes, as students seek out schools where they feel safe. It helps that Vice President Kamala Harris is a graduate of historically Black Howard University. That’s the same school that premier basketball player Makur Maker committed to in 2020 — the first ESPN five-star recruit ever to play for an HBCU, and part of a growing wave of Black athletes choosing such schools over traditional sports powerhouses. And it’s where Nikole Hannah-Jones of the Pulitzer-winning 1619 Project found a home after UNC-Chapel Hill initially denied her tenure last spring, along with National Book Award winner Ta-Nehisi Coates. “We’re entering a golden age for HBCUs,” Abbott says. “It’s really exciting. Students are interested in institutions they haven’t even considered before.”

The HBCU revival is one of those unexpected consequences nobody could have predicted before COVID made us all hit pause, take a breath, and reevaluate where we stand. It’s no coincidence that such a social storm erupted during our Great Pandemic Timeout, when so many of us no longer had busyness as an excuse not to consider what matters, what doesn’t, and what should. As students and professors and administrators abandoned college campuses and hunkered down at home, they got the chance to see themselves and their institutions at a remove. They gained the perspective of distance. And that makes what comes next crucial for American colleges and universities.

Before the spring of 2020, Chris Fiorentino never expected to be making life-and-death decisions for the student body at West Chester U. “It’s certainly been an unusual, challenging year,” he says. “There’s been a lot of pain and suffering, a lot of financial loss.” But like Abbott, he’s also seen new opportunities arise. His school of nearly 18,000 students, he says, is in great financial shape and has grown steadily over the past decade. “We have a beautiful campus in a beautiful college town. We have smaller class sizes, for that small-college feel.” Making test scores optional for 2020 and 2021 increased applications from students of color. For the third year in a row, a national publication covering diversity in higher ed named WCU a “Most Promising Place to Work in Student Affairs” for 2021 — one of just 30 institutions so honored nationwide. West Chester’s doing so well, Fiorentino says, that it may add new dorms: “We’re not oblivious to the demographics. But we believe we can stabilize enrollment. And we know from research that students who live on campus are more successful in school.” Right now, he says, WCU leadership is going over lessons gleaned from the pandemic to decide what to carry forward: “There’s a lot of hard work being done, focusing on what society needs.”

Speaking of West Chester, in June, Temple University announced the hiring of a new president who’s a native of that town: Jason Wingard. The first Black president in the school’s 137-year history, Wingard was most recently a dean and professor at Columbia; he’s also served in leadership positions at Stanford and Penn and worked for Goldman Sachs. The chair of Temple’s board of trustees cited the new president’s combination of “academic accomplishments with real-world experience” and noted, “He understands the future of education is changing.” Wingard became one of four Black academics holding top faculty and administrative posts at Temple, two of whom are women — also a first for the school. Tuition for an in-state student to go to Temple full-time for two years, with room, board and fees, is now about $3,000 less than one year of boarding at the Hill School — and that’s without any financial aid. West Chester costs much less.

Now all we need in order to build on the real progress spurred by the pandemic is some recognition by parents — and students — that college admission isn’t a zero-sum game. Another child’s good fortune isn’t your child’s loss. I saw that with my own kids, for whom fancy private colleges didn’t mean happiness or fulfillment. What did? Getting the hell out by spending two semesters abroad in a developing country. Getting tossed out, and having to start over, more humbly, at a community college. Life is full of surprises, not all of them happy. But this remains true: A rising tide lifts all boats. Maybe you could root for somebody besides your own family to get ahead. Who knows? Your offspring might wind up at one of those mid-tier public universities with lots of low-income kids and very good outcomes. Like, maybe, Temple or West Chester — places with thoughtful, caring presidents and admissions staffs determined to iron out society’s inequities. You’d think any parent would be proud to send a kid to a school like that.

Published as “The Great College Reckoning” in the September 2021 issue of Philadelphia magazine.

Philadelphia magazine is one of more than 20 news organizations producing Broke in Philly, a collaborative reporting project on solutions to poverty and economic mobility in the city. Read all our reporting here.