Help Me, Doctor! I’m a Philly Sports Fan

What do you do when a game ... isn’t just a game anymore?

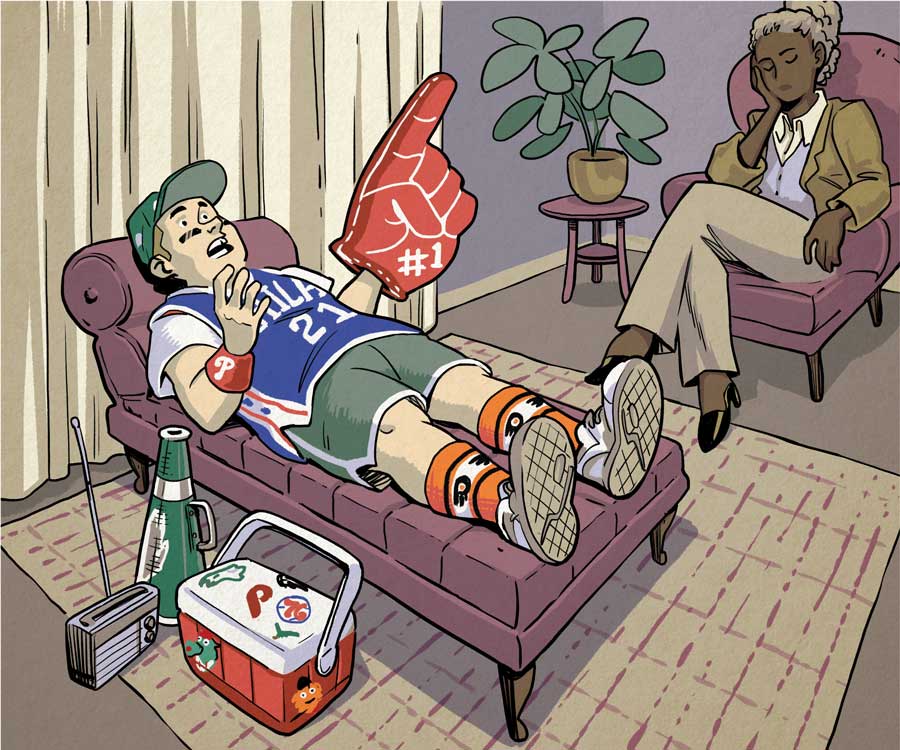

Illustration by James Boyle

Back in May, as the Sixers were a few games away from snagging the best regular-season record in the Eastern Conference, sportswriter John Gonzalez took to Twitter to tout an Inquirer story: “Congrats @PhillySport on creating the most Philly headline of all time.” He included a screenshot of said headline:

First-Place Sixers Showing Flaws Amid Eight-Game Winning Streak

That headline-writing genius managed to encapsulate the sum total of a lifetime of Philly fandom in 10 brief words — the hope, the joy, the sorrow, the ever-present sense of impending despair. Oh sure, we’re in first place now, but we know what’s coming! Remember the Phils in the summer of ’64?!?

Okay. Maybe that epic breakdown — the Phils lost 10 straight games in September to blow a six-and-a-half-game lead — was more than half a century ago. I was seven years old. But to this day, I can picture my dad on the chenille sofa at our house in Glenside, son-of-a-bitching as our newfangled RCA TV chronicled what came to be known as the Greatest Collapse in Sports History. I’ve spent my entire grown life under its gloomy shadow, seen it color every victory with the bitter tinge of irony. Andrew Bynum? Markelle Fultz? Carson Wentz? Pffft. We’ve been here before. We know how this goes.

Reams have been written, by Gonzalez and others, on the woes of the Philly sports fan — the expectations raised and dashed, the long parade of false saviors, the, um, somewhat inappropriate behavior. Popcorn, anyone? That Santa thing. The guy who barfed on that kid at a Phillies game. I got yer Process right heah! But in all my decades as a member of the club in good standing, it never once occurred to me to ask: Does it have to be this way?

Then came the pandemic, with its endless stretches of ennui and nothingness. Apologies to those who spent their quarantines in the company of small children or aged relatives or death. I spent mine sitting at a laptop in my kitchen, correcting fellow writers’ commas and dashes, dropping in on Dr. Fauci, wishing like hell for some relief from the tedium. March Madness turned to sadness. Baseball took a breather. The Eagles imploded. What else is new? As sports seasons revved up again in fits and starts, I was forced to reckon with the fact that my fandom had gotten out of hand. I wasn’t enjoying the games anymore. They were only a source of frustration and aggravation. Like the Inquirer’s headline writer, I was haunted by the spirits of sports seasons past. The Phillies’ bovine bullpen? Another red card for José Martínez? Ben Simmons, shoot the motherfreakin’ ball! You guys are really PISSING ME OFF!!!

Which is when I realized: I could just stop watching.

Which is when I realized: No. I couldn’t.

Which is when I realized: Girl. You need professional help.

Joel Fish tells a story about when his son Eli was eight years old. “He had one of those Little Tikes basketball nets in the backyard,” Fish says, “and one day, he hit a one-in-a-million shot. I shouted, ‘Hooray for Eli!’ And my wife, who often keeps me grounded, pointed out that I’d never, ever reacted that way to one of his art projects. There’s something about sports that activates my emotions.” Tell me about it, Doc.

For the past 30 years, Fish has been a sports psychologist, helping Olympic, pro, high-school and college athletes deal with those emotions and their repercussions. And he assures me I’m not the only Philadelphia fan who’s ever reached out to him. “Welcome to the club,” he says wryly. “When the Eagles lose on Sunday, you can feel it in the city on Monday. Sports just pushes our buttons, not only in America but all over the world.”

But my sports-fan problem is getting worse, I tell him. I’m watching more games and enjoying them less. Fish says that’s not unexpected and points to a couple of factors that have ratcheted up fan frenzy in the recent past. “I think it’s partly because sports are so accessible to us now,” he posits. “When I was growing up, you’d see one college basketball game a week. Now, you can see all 162 Phillies games.” Not to mention 1,356,874 of those dumb ads for sports-betting apps featuring not-quite-hot girls. And then there’s social media: “I had an NBA player who once told me, ‘I can do 99 things right and then one wrong thing, and the whole world knows about it the next minute,’” Fish recalls. At the same time, the average age of pro athletes has been coming down: “The leagues keep getting younger. Players don’t have time to learn maturity. They have to deal with more pressure at a younger age.”

At the Center for Sport Psychology, Fish’s Rittenhouse practice, he focuses on helping players hone their ability to perform under all that pressure and sustain their confidence during what he calls “the ebb and flow of the season.” Then there are the challenges of trying to have some kind of personal life beyond sports: “You have to find balance. You have to compartmentalize and set boundaries. And you have to take care of your significant relationships.” Weirdly enough, that all sounds exactly like what I need help with as a Philly fan.

Fish isn’t surprised. Psychological studies, he says, show that over time, our identification with athletes has increased: “We feel that we won, or we lost. We feel like we know them, because we see them so much” — on TV, in the press, on Facebook and our Twitter feeds. And they’re starting to push back against that oversharing; witness Naomi Osaka’s withdrawal from this year’s French Open after she refused to participate in post-match interviews.

To be sure, Fish adds, there are some positive aspects of fandom: “Sports unites us — rich, poor, Black, white, urban, rural — at a time when there’s so much divisiveness in our country. You turn on WIP, and everybody’s talking about the same thing: ‘We got DeVonta Smith!’ It’s something that we have in common with other people. We affiliate. We have our group. We wear our Eagles gear.”

Of course, not everyone cares about athletics to the same extent. Fish divides sports aficionados into four categories. You have your totally devoted fans, he says, who’ll watch any contest of anything at any time — you know, the audience for those bizarre off-peak sports-network showings of footvolley and curling. Then you have loyal fans, who’ll watch the Sixers but aren’t interested in the Hornets or the Kings. One more rung down are casual fans, who skip the weekly contests but get invested once the playoffs start. At the bottom of the heap are “bandwagon fans,” who watch the playoffs but only so they can munch wings and drink beers with their friends: “It’s more a social thing.”

But Philly, I say. Surely, Philly fans are special. More committed. More intense. “Well, it’s sort of encouraged here, isn’t it?” Fish says. “We take pride in it: We’re passionate, we care. It’s an important part of our identity, our civic pride.” He remembers having season tickets for the Eagles back when they played at Penn’s Franklin Field in the 1960s, when they went through coaches like Cheetos and rarely won games. It didn’t dampen fans’ passion. A cheer is just the inverse of a boo. “A football-player client once told me,” says Fish, “‘There’s no better place to win — and no more difficult place to lose.’”

So maybe if I moved to a different city, I wouldn’t care so much about winning?

Fish doubts it would help at this point: “You could live in the Samoan Islands and watch Phillies games and still care just as much.” He pauses. “But I guarantee, if you move to Tampa, you’re not going to relate to the Rays in the same way.”

Stephany Coakley is from even further away than Tampa: She was born in the Bahamas. She headed to grad school post-college intending to become a clinical psychologist. But after earning her master’s degree and spending a decade as a therapist in Philly, “I got burnt out,” she says matter-of-factly. She went back to school for a PhD in exercise and sports science. That’s when her career took a sharp turn: “I went to work for the Army as a mental performance consultant. I was there for 10 years.” Then, in 2017, she took a newly created position at Temple University: its first-ever Senior Associate Athletic Director for Mental Health, Wellness and Performance.

Woah. I mean, sure, there are all those clichés about the playing field as battlefield, but isn’t it just metaphor? Coakley begs to differ. “The strategies for soldiers and athletes are the same,” she says. “How hard athletes go, their focus, the adaptability sports require — it’s the same deal with soldiers. There’s an inherent leadership component to both. There’s a hierarchy: You have the officers and the enlisted soldiers, and you have the coaches, the front office and the talent. Athletes and soldiers both make huge sacrifices. They both require discipline and the physical attributes of performing. They both train every day, for four or five hours a day.” And there are other similarities that aren’t immediately apparent, like life on the road. An NBA player might be in Portland one day and New York City the next day. A soldier might be in Germany one day and the next in Iraq.

But what about “It’s just a game”?

“Oh, the stakes are very different,” Coakley agrees. “For an athlete, it’s not about life or death. It requires a lot of work, but everybody’s going home to their families at the end of the day.”

Interestingly, Coakley says, soldiers use a lot of sports metaphors, while athletes often speak in the language of war. In many ways, the windup to performance is similar. Think, she suggests, of locker-room chanting, or the intense, ritualistic haka of New Zealand rugby players. Does that sound like “just a game”?

This is something I ask Joel Fish about: whether sports today serve as a sort of cheap substitute for the regular tribal warfare humans used to engage in. “If I put my psych cap on,” he says, “I might talk about how the mentally raw aspects of human nature have played out in different environments over time. Gladiators, boxing, wrestling — it’s all the ultimate reality show.”

So, I ask Coakley: What are some strategies you use with soldiers and athletes that I could adopt, as a lowly fan? She suggests I set boundaries as to how many games I take in during any given week: “Why watch if they’re driving you up a wall?” Because my husband likes idiotic rom-coms and superhero movies, and sports are the only entertainment we can agree on, I think but don’t say. If I feel myself getting worked up, she says, I should take a 10-minute timeout, then go back to the game once I’ve calmed down. I can practice “box breathing,” a technique in which you inhale deeply, hold the breath, then exhale slowly, to induce calm. Most interestingly, she proposes that after a game is over, I allow myself 10 minutes “to be pissed off, to rant, whatever. Then go back to whatever else you have going on.” I’m sure my kids wish I’d adopted that habit for Sunday Eagles games when they were small and a loss would make Mom grim and curt for the rest of the day.

“These are just variations of what I’d say to someone who’s having problems with social media,” Coakley tells me. “Take breaks! It’s triggering! Don’t watch endless George Floyd videos!” Whether it’s a tight game on TV or scrolling through Uncle Charlie’s racist rants on Facebook, stressors affect your nervous system the same way: “You’re making your body work hard. Your blood pressure goes up. Your heart rate goes up. There’s an increase in muscle tension, changes in breathing.” No wonder watching the Phillies’ relievers is so exhausting.

But why, if my sports jones takes such a toll, did it intensify during the pandemic, when there were fewer games but so many other stressors in my life? It could be, Coakley proposes, that the hiatus so many of our teams took made me miss them acutely and then overreact when they started up again: “Like when you get back together with an ex and it’s stronger than ever.” That said, she confesses, “I’ve had the opposite happen to me. I haven’t been able to get back into sports yet. The pandemic definitely impacted people’s perspectives.” She saw this dichotomy in the college athletes she works with. For some of them, the abrupt break from competition was a blessing: “Imagine if you’re coping with an injury and suddenly you have seven months to recover.” And she saw students use the unexpected freedom “to tap into other aspects of their identity and come together to bring awareness to social injustice in all its aspects” — marching for Black Lives Matter, setting up book clubs, working on voting rights campaigns. For others, though, the enforced leisure only pointed up how absurdly imbalanced their lives are: “It’s school and sports and nothing else,” Coakley says, “except for social life lite.”

That’s something Meg Waldron knows all about. Back in the 1980s, she was one of the nation’s most elite runners. At the Penn Relays, she recorded the fastest-ever high-school leg in the 800 meters. She set a state record at 3,000 meters that stood for nearly 40 years and earned a full scholarship to run track and cross-country at the University of Virginia, a D-I school. Today, she has a master’s in sports psychology and runs her own counseling/mentoring business, inspired by one simple mantra: What can I offer that wasn’t available to me as a young athlete?

What wasn’t available? “Mental support around how to process feelings of challenge, disappointment, being overwhelmed,” she answers promptly. “How to build a resilient mind.” That … sounds like something I could use, as a Philly fan.

Waldron laughs. “When you’re an athlete,” she says, “there are certain things you can control. But fans control nothing.”

Nonsense, I toss back. What about the much-touted home-field advantage?

Back when she ran that fastest leg at the Penn Relays, Waldron recalls, “At a certain point in my first lap, I heard 40,000 people on their feet, cheering for me. We won that race. The roar of the crowd had a huge impact on me. But in general, athletes are too focused to pay much attention to the crowd. They put in all that work, collaborate with the team and the coach for months — that has a bigger influence. Fans help you rally, but that’s a small part of your performance.”

Having once interviewed prominent Philadelphians about their Eagles game-day superstitions — ranging from Dom Giordano’s nonstop pacing to Ajay Raju’s constant Tostitos ingestion to Christine Flowers’s special Iggles poem (“Use your might for Reggie White/Make a scoreski for Jaworski”) — I’m not exactly convinced. There’s absolutely no question in my mind that if I don’t leave the living room for the kitchen anytime Jake Elliott is kicking a field goal, the team is doomed.

“You control nothing,” Waldron reiterates, shattering a lifetime of illusion. “You have no influence on how the team performs. Being a fan, or an athlete, is an exercise in letting go.”

I sit for a moment, allowing this to sink in.

“That’s been compounded by the pandemic,” Waldron begins again, more gently. “It’s not just the games that are beyond your control. The world is out of control. So the question becomes: How do you acknowledge that you have no control, let go, and be hopeful for the best?”

How does one do that?

“It is just a game,” she reminds me. “Are you letting it affect your health? Your diet? Your sleep? Your relationships? It’s really important to step back and have some perspective.”

Easier said than done.

“I know,” says Waldron. “In Philly, that’s the culture of the fan experience. It becomes part of your identity. And when their identity is threatened, people react in different ways. Some people get aggressive.”

I DON’T KNOW WHAT THE FUCK YOU’RE TALKING ABOUT, MEG!!!!!

Which reminds me that when I ask Joel Fish about strategies I might use to mitigate my mania, he makes some suggestions along the same lines as Coakley’s: Choose a mantra to repeat during games when you feel you’re getting out of control. Take deep breaths. Take timeouts. But he also guesstimates that having a game plan to moderate my emotions would result in, at best, a lessening in intensity of five to 10 percent. “You want to keep the passion,” he tells me. “You want to keep your mental edge.”

I do. I mean, I think I do?

He then suggests I should examine my attitude toward winning and losing and why it’s so important to me. Which opens up a whole other can of worms. Whenever I watch the Phillies or the Sixers or the Eagles, I’m reminded of my father. The sixth of seven kids, the fourth of five boys, he was an athlete, a coach, and an avid sports fan all his life. Watching the Phillies or the Eagles with him was an important part of my adolescent years.

When I mention this to Fish, he nods. “I’m thinking of my dad,” he tells me. “It’s insidious. I remember watching games with my grandfather and my father. Three generations of fans watching together — that’s such a part of the fabric of community here. It’s a phenomenon in this city. It’s different in Florida, in Tampa or Miami, where so many fans were born somewhere else and moved there. The intergenerational aspect isn’t as strong.”

“That’s how my dad and I bonded,” Stephany Coakley tells me. “He was a sports guy. If I wanted to hang out with him, I had to go to a sporting event. He wasn’t going to go to a dance. It’s a way for fathers and daughters to connect.”

“That’s how I got close with my dad,” says Meg Waldron. “I was his little tomboy. It was a way of getting attention. I’m one of nine kids.”

The last time I watched a Phillies game with my father was in September 2007, in his assisted-living room in Doylestown. I could tell he wasn’t going to live much longer, even with assistance. It was the first time I’d ever seen him not focused on the game. He died two days later. The following year, the Phils won their first World Series in more than a quarter-century. I’ve never quite forgiven them for that.

I wonder sometimes, as I watch our $177 million point guard pass on an easy layup in the final moments of a give-it-all-you’ve-got game, what it would be like to live in a place that churns out sports dynasties: Pittsburgh in the 1970s, L.A. in the Showtime era of Magic and Kareem, New England when Tom Brady was there. Places where the teams win all the time — where you can count on going to the playoffs and probably beyond. The striking thing about Philly’s championships is that they’ve all been one-and-done. Well, except for the Flyers’ two Stanley Cups in a row in the mid-’70s. But I’ve never followed hockey. I used to wonder why I didn’t, until I realized: neither did my dad.

Would I be a happier person — a better wife, mother, friend, employee — if I’d grown up a Yankees fan in the Bronx?

And then I think about Gritty. I know, I know — more irony, that the mascot of a team I don’t give a damn about has come to symbolize Philly sports fandom. Gritty isn’t the best-looking mascot in the big leagues, or the smartest; remember that time he shot a guy in the back with a t-shirt cannon? Gritty’s been investigated for assault by the police. He’s been described as “maniacal,” an “orange horror,” “an acid trip of a mascot.” CBS’s Pete Blackburn called him “pure, unadulterated nightmare fuel.”

But you know what Gritty has?

A resilient mind. Well. Assuming Gritty has a mind.

So do I, I guess. I’m way too old to move now, to start anew. My kids, my siblings, my extended family are all here. They, too, once watched the games with my dad. I’m a Philly sports fan, for better or for worse. And hey, it could be worse.

“My best friend is a Dolphins fan,” Stephany Coakley says, laughing. “Every single year, she’s stricken right from the first game. Don’t expect the worst, though — even if that’s what happens! We don’t control any of this stuff. Tell yourself: Let’s see where this thing goes.”

I thank her. And I mention I’m a big fan of Temple football.

“Oh, Lord,” she says swiftly, sympathetically. “You are an eternal optimist. That’s one thing I do love about sports, though: Anything can happen. On any given day, anybody can get beat!”

Published as “Help Me, Doctor, I’m a Philly Sports Fan” in the August 2021 issue of Philadelphia magazine.