One Moment From John Fetterman’s Past Could Derail His Senate Bid

The lieutenant governor has been on a meteoric rise from small-town mayor to darling of the national punditocracy. But one lingering incident from 2013 — and how it plays in places like Philly — may determine just how far his political journey goes.

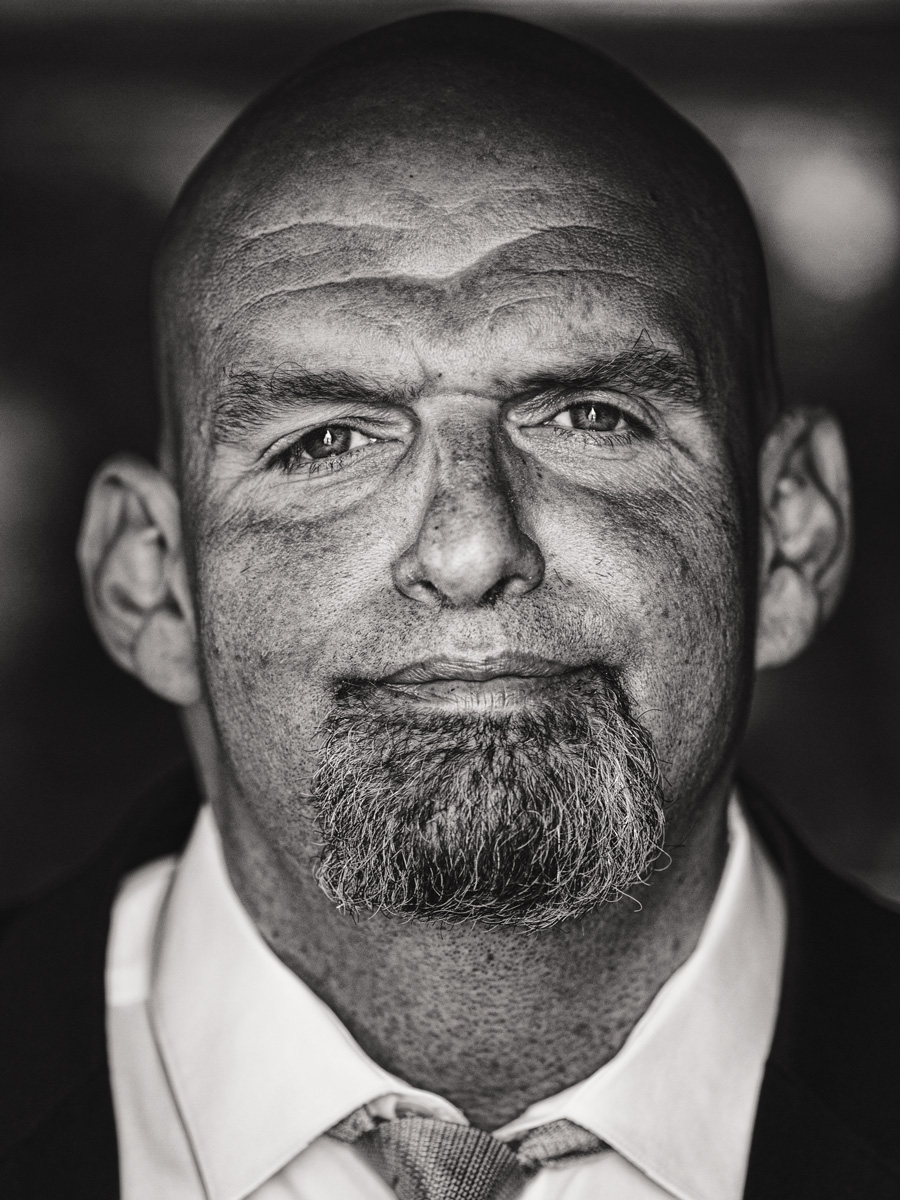

John Fetterman. Photograph by Kevin York

It’s the Ides of March, a date that lives in infamy, the day that Julius Caesar was betrayed and butchered by members of the Roman Senate — friends, Romans and countrymen, to a man. That was back in 44 BCE, and it’s been a bad-omen day ever since. But John Fetterman, the hulking lieutenant governor of Pennsylvania and, as such, the president of the state Senate, which he’s moments away from gaveling into session, isn’t sweating it. After all, he gets Et tu, Brute’d by the Republican-controlled Senate on a semi-regular basis.

At this moment, he’s posing for a staffer’s camera on the sun-drenched balcony adjoining his office in the state Capitol complex, unfurling a bright yellow Gadsden Flag — retrofitted with marijuana leaves and the motto “Don’t Tread on Weed” — in the yawning chasm between his meaty outstretched paws. The pro-pot flag, along with a half-dozen or so homemade rainbow pride flags that, draped over his shoulders, make Fetterman look like a Roman emperor crossed with Wavy Gravy, were sent to his office by supporters from all over the U.S. and points beyond, one from as far away as Australia. “I don’t want to hang any today just because they’re going to be taken down in an hour,” Fetterman says by way of explanation for the photo session, the pics from which he’ll blast out on social media. “But I do want to thank everyone.”

The flags are replacements for ones that had been hanging from his balcony since his first year in office in 2019. The display so irked the Republican majority of the state legislature that they tucked a provision into a budget bill prohibiting the display of “unauthorized flags” on the exterior of the Capitol. In January, when Fetterman politely refused to comply, maintenance workers, at the behest of Republican leadership, confiscated his array.

Harrisburg, it should be clear by now, is a place where good people go to become less so. Almost everybody leaves this town in tears or handcuffs. This isn’t hyperbole. The General Assembly — the largest full-time state legislature in the Union — was ranked the sixth most corrupt in America by a nationwide quorum of statehouse reporters in 2017. Bipartisanship? We haven’t had that spirit here since 2012, when Republican Speaker of the House John Perzel shared a prison cell at Camp Hill with Democratic Speaker of the House Bill DeWeese.

Fetterman is in prime position to buck that trend. Before he was elected lieutenant governor, Fetterman’s only claims to fame as a politico were a failed 2016 U.S. Senate run and three-plus terms as mayor of Braddock, PA, a perpetually afflicted borough on the banks of the Monongahela River, a few miles southeast of Pittsburgh. But since he took office — an office whose duties he’s described as being Governor Wolf’s “anger translator” — his growing ubiquity as a blunt-talking progressive firebrand on Twitter and cable news has made him a beloved national political figure in lefty redoubts across the fruited plain.

As his profile has grown, so has the tension between him and the GOP. In January, during a heated dispute about seating a newly elected Democrat — even though the election had been certified — Republicans used an obscure parliamentary maneuver to have Fetterman removed from the Senate floor. Just like that, the president of the Pennsylvania state Senate was rat-fucked out of power — for a day, anyway. As Caesarian back-stabbings go, this would rate as a mere flesh wound, but the message it sent was clear: This isn’t a statehouse where the people’s business gets done; it’s a circus of cruelty. Small wonder he wants out of the clown car.

When Pat Toomey announced back in October that after nearly 20 years on Capitol Hill, he would be vacating his U.S. Senate seat in 2023, he opened up a Pandora’s box of political intrigue. Fetterman was the first to officially throw his hat in the ring and instantaneously became the front runner by raising a record-setting $3.9 million in the first leg of what’s expected to be one of the bloodiest and most expensive Senate races in the history of Pennsylvania politics.

This will be his second bite at this particular apple, and a test of the evolving electoral calculus in the state. Fetterman first ran for Toomey’s seat as something of a party outsider in 2016 and finished a respectable but distant third behind Katie McGinty, the safe-as-milk choice of the party mandarins, and Joe Sestak, the pride of Delco. Dem party politics have undergone a revolution since that first Senate run, though, and the arc of electoral justice appears to be bending Fetterman’s way. The bread and butter of his campaign — a $15-per-hour minimum wage, legalized weed, health care for all, and wholesale reform of the criminal justice system — are policy positions that were once well outside the comfort zone of most Democrats running for office but have since become the mainstream. Not that Fetterman is crowing about it. “Anyone who declares themselves the future of the Democratic Party usually becomes the past,” he says.

And that seems wise. As the ground continues to shift, there’s considerable danger ahead for Fetterman, particularly in the form of a disturbing-on-its-face and decidedly off-brand incident from his past, the valence of which seems to grow more malignant every time police murder an unarmed Black man. Depending on how he plays it — and how it plays in places like Philadelphia and Pittsburgh, where the Black vote that’s become so crucial to Democratic victory in the state is concentrated — it will either be his Chappaquiddick or his Rubicon.

At approximately 4:30 p.m. on January 26, 2013, John Fetterman, then in his second term as mayor of Braddock, was standing in front of his house, playing with his then-four-year-old son Karl, when he heard gunfire. A lot of gunfire. “I heard approximately a dozen or more what clearly sounded like assault-rifle gunshots go off,” he told a TV reporter from the local ABC affiliate at the time. “I didn’t know if it was a rampage. I didn’t know if it was a drive-by. I didn’t understand. … At that point, I made a decision as a parent, and as a mayor, to intervene until the first responders could get there and sort it all out.”

He hustled his son into the house, called police, and went to investigate. When he came back out, a man named Christopher Miyares ran by, dressed in a black tracksuit, his face masked by a black balaclava and goggles. Miyares appeared to be running from where the sound of gunfire originated and toward the elementary school. This was just a few weeks after the Sandy Hook school massacre, so Fetterman jumped in his black pickup and took off in hot pursuit.

What happened next is in dispute.

Miyares is Black, but Fetterman says because the man was bundled up against the cold, it was impossible to determine his race or gender. Miyares told police that Fetterman caught up to him and pulled a shotgun on him. Fetterman admits he pulled the 20-gauge shotgun from his truck after Miyares refused to stop running but denies he pointed it directly at Miyares.

Police arrived, searched Miyares, and, finding no weapons, released him. Later that year, the people of Braddock — a town that was 70 percent Black — overwhelmingly reelected Fetterman to a third term as mayor.

And that, it appeared, was the end of that.

But in 2016, during Fetterman’s first U.S. Senate run, the incident was resurrected, presumably by his Democratic primary foes, in a whisper campaign to journalists, and it’s haunted Fetterman ever since.

In April, the Collective Super PAC, which was formed in 2015 to address the chronic underrepresentation of people of color in elected office, began airing an ad on radio stations WDAS-FM in Philadelphia and WAMO-FM in Pittsburgh, reminding their majority-Black listenerships about the 2013 gun incident. “What gave John Fetterman the right?” a woman asks in the ad. “The police first surrounded the innocent black jogger but then let him go, and then they let Fetterman go, too. Now John Fetterman is running for U.S. Senate and wants our vote, but it’s time for us to finally hold John Fetterman accountable.” The ads seem intended to boost the prospects of State Rep Malcolm Kenyatta, who declared his candidacy for Toomey’s Senate seat in February, right after beginning his second term in the state House.

Born in North Philly 30 years ago, Kenyatta is one of the youngest state representatives ever elected in Pennsylvania and the first openly LGBTQ person of color elected to either chamber of the Pennsylvania General Assembly.

In a turn of events that surprised some political observers, Chardaé Jones, the outgoing mayor of Braddock, endorsed Kenyatta. She cited their kindred pedigrees — both are millennials who bootstrapped themselves out of humble beginnings — and a shared agenda of inclusivity and social justice. She also cited Kenyatta’s anti-fracking stance. (Fetterman believes fracking is a necessary evil.) Fetterman countered with endorsements from Delia Lennon-Winstead, Braddock’s likely incoming mayor, and Rob Parker, president of the Braddock Council.

Kenyatta contends that Fetterman’s actions in the 2013 incident were less a matter of racial profiling than reckless vigilantism. “I don’t think John’s a racist, but I also don’t think John is Batman,” Kenyatta says. “We can’t just have people saying, ‘I live in a community where there’s gun violence, therefore I’m justified in picking up a shotgun and going out and chasing the first person I see.’”

Fetterman has maintained that per Braddock’s borough code, which tasks the mayor with “preserv[ing] order in the borough,” he “had the duty and authority to respond to spontaneous emergencies.”

As for Miyares, in May of 2019 he was convicted of kidnapping and making terroristic threats during a 2018 incident in which, according to published reports, a woman told investigators that he impersonated a ride-share driver, then locked the car doors and pulled a knife on her. After she escaped, Miyares texted to say he knew where she lived and worked.

In April, the Inquirer’s Chris Brennan published portions of a letter from Miyares reiterating that Fetterman pointed the shotgun at him but emphasizing that he doesn’t believe the incident should prevent the lieutenant governor from being elected to the Senate. He’s currently scheduled to be released from prison on April 25, 2022, just three weeks before the May primary. (Miyares didn’t respond to a letter seeking comment.)

The absolute truth of what happened that day eight years ago is likely forever lost, Rashomon-like, in the twilight zone of competing narratives. But the troubling gun incident not only imperils the lieutenant governor’s much-ballyhooed political prospects; it threatens to call into question much of what we know about him — the very mythology of John Fetterman, hulking everyman champion of Braddock.

John Fetterman’s official lieutenant governor portrait hangs on the wall of his office next to a portrait of Governor Wolf, who is wearing a suit and tie. Fetterman, whom GQ recently dubbed “a taste god,” is wearing a gray Dickies work shirt in his. “Believe it or not, that was controversial,” Fetterman says wearily. “These portraits are hung on the walls at rest stops across the state. I’m told people are like, ‘Did someone punk this place and put their own photo up? Guy looks like he works at Jiffy Lube.’” All of which is very on-brand: the grease-monkey chic, the perceived violation of propriety, the pearl-clutching of the swells, the wiseass-ery. Fetterman doesn’t do pomp and ceremony — not willingly, anyway.

It’s why he and his wife, Gisele, declined to move into the lieutenant governor’s mansion out at Fort Indiantown Gap, convincing the powers-that-be to open its pool to the public and pushing for legislation to turn the mansion over to veterans’ programs and National Guard families. He rents an apartment from his brother when he has to be in Harrisburg. The rest of the time, the lieutenant governor resides in a spartan but stylish loft in an old car dealership back in Braddock. “That decision was easy: Nobody owes me and my family a mansion with a chef and a gardener,” he shrugs.

Outwardly, these gestures virtue-signal humility and empathy for the common man, but they are pretty radical moves, and in the aggregate, they send a message that resonates across the political spectrum: Let’s cut the crap, take off the suit-and-ties, ditch the mansions, and get under the hood and fix shit.

The clothing, at least, is also born of necessity. Fetterman, in case you haven’t noticed, is a mountain of a man: six-foot-eight, Mr. Clean haircut, salt-and-pepper goatee, Colonel Kurtz-ian mien. And though it’s rarely remarked on, giants have somewhat limited sartorial options.

John Fetterman suits up, with boots and neon face mask, in his office at the state Capitol. Photograph by Kevin York

Currently, he’s in the best shape he’s been in since he played football for Albright back in 1987. Thanks to a no-sugar-or-grains diet and daily sunrise hikes along the banks of the Monongahela, combined with a walk-don’t-drive ethos that has him clocking seven to eight miles a day, he’s dropped a whopping 150 pounds. He doesn’t boast when the impressive downsizing is noted by a visiting journalist. He winces.

“I’m a little embarrassed that I let it get that out of hand,” says Fetterman, who will turn 52 on August 15th. “With all the stress, I put on weight during my time as mayor, and I finally decided I needed to change the way I eat. I realized the outcomes for old burly linemen aren’t great unless you figure something out.”

When he grew seven inches between his sophomore and senior years of high school, it became apparent that John Fetterman was going to be a great man — a great big man. This came in handy during his tenure in the trenches as right tackle at Albright, where he studied finance and learned how to take a punch. “Your job is to be a brute; it’s nonlethal hand-to-hand combat,” he says of that nasty bit of business. Upon graduation, he enrolled in the MBA program at the University of Connecticut and took an underwriting job at an insurance company. But his plans to follow his father’s footsteps into corporate America were forestalled when his best friend at the time was killed in a head-on collision on his way to drive Fetterman to the gym. It was a shattering experience, one that caused him to rethink everything about his life. He still gets emotional talking about it. “The life of a good man was taken,” he says. “I wanted to effect some positivity in the world.”

He volunteered to be a Big Brother and was assigned to an eight-year-old Puerto Rican boy named Nicky Santana whose father had died of HIV not long after he’d infected Nicky’s mother, who would succumb a few months later. Fetterman made a deathbed promise to her that he would do whatever he could to make sure Nicky got a college education. Nobody in Nicky’s family had ever made it past middle school, but in 2009, he graduated from Washington & Jefferson College. Now 35, Santana works for a nonprofit in New Haven that assists the disabled.

In 1995, Fetterman joined the second class of Bill Clinton’s AmeriCorps, for which he ran a computer lab in a poverty-scarred neighborhood in Pittsburgh. In exchange, AmeriCorps partially funded his graduate degree in public policy at Harvard’s Kennedy School. After Harvard, in 2001, he went back to Pittsburgh to do social work and was assigned to nearby Braddock, a once-thriving steel town utterly decimated by decades of deindustrialization, white flight and crack cocaine. To Fetterman, though, it somehow felt like home. So he put down roots, rolled up his sleeves, and went to work.

In 2005, he ran for mayor of Braddock and won. In his three-plus terms — for which he was paid the princely sum of $141.67 a month — despite often ferocious pushback from Borough Council, Fetterman accomplished the following:

There are now a handful of restaurants in a town that had none, as well as a public square, a playground, and an urgent-care facility to replace the hospital that shuttered in 2010. He turned an abandoned church he’d purchased into a community center. Trash-strewn vacant lots have been turned into urban farms. In his role as chief law enforcement officer, he reformed the police department, firing bad-apple cops, de-emphasizing overpolicing and mass incarceration, and emphasizing community engagement and public safety. Gisele set up the Free Store, which gives away food, clothing and housewares, donated by area retailers, to those in need.

When Fetterman came to Braddock in 2001, the murder rate was spiraling out of control. He decided to run for mayor when two students he was mentoring were gunned down in the street.

“When John became mayor, he always had a police scanner,” says Lisa Freeman, a social worker who worked in Braddock alongside Fetterman in the bad old days of the early aughts. “And every time there was an emergency 911 call, John would be one of the first responders. If I was in trouble and needed to call him, you’d see him come running, from blocks down the street. I mean, it was very unsafe here, they were shooting day and night. There was no safe place here; nothing was off limits. By 2008, the crime rate had gone down tremendously. John should take most of the credit for that.” During one five-year stretch of Fetterman’s tenure, from 2008 to 2013, there were zero murders recorded in Braddock.

Things are far from perfect there, granted. But at a moment when cities across the country are grappling with a gun violence epidemic, solutions to which seem few and far between, that’s a big deal. You can say what you will about John Fetterman, and Lord knows many do, but this much is undeniable, and because he’s too humble to say it himself, I’ll say it for him: Against all odds, and with nothing to gain and everything to lose, including his own life, he brought hope — or at least the green shoots of hope — to a place where there was precious little.

Fetterman lives in the shadow of the Edgar Thomson Steel Works, one of the last vestiges of Western Pennsylvania’s vaunted steel industry, in a disused Chevy dealership he purchased and turned into a multi-use space. On the first floor is Superior Motors, a fine-dining restaurant, owned and operated by chef Kevin Sousa, that provides gourmet meals for Braddock residents at a 50 percent discount. On the second floor is a spacious loft tastefully appointed with exposed brick walls and hardwood floors that serves as living quarters for Fetterman, Gisele, their three children — Karl, 12; Grace, nine; and August, seven — and Levi the rescue dog. On the wall above the kitchen sink is an old sign that used to hang at the entrance to the borough. It says WELCOME TO BRADDOCK COMPLIMENTS OF. Overtop the names of some long-extinct local business sponsors, somebody has graffitied the word CRIPS.

In his home, Fetterman and I sit and talk at length about many things. Most of what he says, he’s said many times on television or on Twitter, and it’s been parsed over and over by journalists. But there are two soul-baring moments in the conversation when his beefy baritone quavers and his eyes well up.

The first is when I ask him to tell me about the numbers starkly tattooed in black on his arms, reminiscent of the serial numbers tattooed on concentration-camp survivors. On his left arm is the number 15104, Braddock’s zip code. On his right are nine numerical dates — the dates of murders that happened in Braddock on his watch. He struggles in vain to maintain his composure through a few of the stories: the pizza-delivery guy with a wife and kid who was gunned down while doing his job; the man whose skull was blown to pieces in an assault-rifle battle; the two-year-old who was raped and brutalized by her father, then wrapped in a blanket and left to freeze to death in the woods.

The second thing that makes him choke up during our conversation is his work as chairman of the Pennsylvania Board of Pardons, another of the lieutenant governor’s primary duties. For him, the dispensation of mercy to the deserving isn’t a job; it’s a calling. “If there was a mechanism that allowed me to continue doing just this for the rest of my life, I would give up everything to make that happen,” he says. “I would step down as lieutenant governor if that would make it happen.”

“I think the Senate race started too early,” says Philly political guru Larry Ceisler. “This is what happens when you announce your candidacy too early: You become a target.”

The Pennsylvania Board of Pardons meets four times a year to consider the ever-growing pile of applications for a pardon or a commutation submitted by inmates at state prisons across the Commonwealth. There are five people on the board: the lieutenant governor, the state attorney general (Josh Shapiro), and three other members with relevant expertise picked by the governor and approved by the state Senate. Votes on cases involving death sentences and life imprisonment must be unanimous; otherwise, recommendations for a pardon/commutation (the conferring of which ultimately lies with the governor) are denied.

With Fetterman at the helm, the board has been wading through the huge backlog of applications at a determined clip. Shocked and shaken by the overwhelming majority of elderly Black faces among the 5,400 inmates currently serving life sentences in Pennsylvania’s state prisons, Fetterman has made it his mission to shift the emphasis from cruelty to compassion. “We’re making it all about second chances, about redemption and forgiveness and completing the circle,” he says. “People think the face of life in prison is Hannibal Lecter, but sometimes it’s the face of Morgan Freeman in Shawshank Redemption.”

Two people Fetterman deemed worthy of a second chance are Lee and Dennis Horton, brothers from North Philadelphia who, until their release in February, had served 27 years of life sentences as accessories to a murder they maintain they had no part in. In one of the many cruel ironies of the U.S. justice system, the man who confessed to committing the murder was released in 2008. By all accounts, the Horton brothers were model prisoners, counseling fellow inmates struggling with incarceration, teaching yoga, convincing their peers to act in and build props for productions of plays they wrote about atonement and restorative justice.

Two wardens and assorted deputies, not to mention the state secretary of corrections, advocated for their release at a Board of Pardons hearing in December of 2020. When it came time to vote on the Horton brothers’ request for a commutation, Fetterman wept openly as the other board members voted “yes”; when his turn came, he was too overcome with emotion to speak. AG Josh Shapiro, who’s locked horns with Fetterman in the past over whom to let out and whom to keep in, answered for him: “I’m a yes, and I think the lieutenant governor is a yes as well,” he said over Zoom. The Horton brothers were watching all of this go down from the warden’s office at SCI Chester, where they were incarcerated.

“This is a man who supported us with everything he had in him; he was all in, emotionally, physically,” Dennis Horton told me back in April, just a few weeks after he and his brother were released from prison. “He gave what he had to help free us from the clutches of a life sentence.”

“He saved our lives, because life in Pennsylvania means you die in prison — they call it ‘death by incarceration,’” said Lee. “When he broke down, I was taken aback, because you don’t expect a guy that big to be that emotional.”

“Especially with all those tattoos on him,” Dennis chimed in. Since their release, the Horton brothers have been hired by Fetterman’s U.S. Senate campaign to coordinate voter outreach in Philadelphia.

In many ways, the Democratic primary next May could end up being a referendum on the gun incident. It could also prove to be an enlightening case study in how much the electoral calculus has changed, or not, in a purple state where conventional wisdom long held that the center was the path to victory. Is winning Pennsylvania still about converting independents and persuadable voters in the messy middle? Or is this now a Meghan Trainor state — all about the base?

Fetterman — pro-pot, anti-incarceration, reducer of gun crime, anti-elitist, champion of all that the MAGA crowd despises — presents about as lefty as they come, but with a hint of Bernie Sanders populism that could play in certain corners of the right. The Miyares incident, as it’s been portrayed in the media and by his opponents, seems wildly out of character. Could it hurt him with the base? Could it persuade the party, again, to throw its weight behind a more traditional candidate?

“It becomes a question of how you’re going to get Black women to turn out, because that’s the most engaged voting block for the Democrats,” says Mustafa Rashed, a Democratic political consultant based in Philadelphia. “And I think [the gun incident] has aged poorly, given the current environment.”

Regardless of the reality, the optics aren’t good, and Fetterman’s inability to make the incident go away is a patch of turbulence in what has otherwise been a masterful political ascendance. That he’s been standoffish about Miyares — “You can take the word of a man who attempted to abduct an innocent woman at knifepoint … or a man who was elected to four terms as mayor of a town that’s 80 percent Black,” he told me — has raised eyebrows.

“How would I handle this if Fetterman was my client?” asks Rashed. “Apologize for it, which to my knowledge hasn’t happened. You apologize, and it goes away. Never too late to do the right thing. To be defiant about it is a curious approach.”

Ultimately, how this shakes out may depend on who else is on the primary ballot. Besides Kenyatta, others who have declared include Val Arkoosh, chair of the Montco board of commissioners, and Philly State Senator Sharif Street. And there are rumblings about a raft of other politicos poking around: suburban Philly U.S. Reps Madeleine Dean and Chrissy Houlahan, Lehigh Valley U.S. Rep. Susan Wild, Allegheny County U.S. Rep Conor Lamb, Pittsburgh mayor Bill Peduto, even, say insiders, Mayor Jim Kenney, among others.

“Miyares could cut into his support with African Americans, but I don’t know how much it matters in Philly” if Kenyatta or Sharif Street is on the ballot, says Neil Oxman, a political consultant and co-founder of the Campaign Group. “I think if voters disqualify him because of this incident, they weren’t going to vote for him in the first place.”

Oxman also believes that Fetterman’s image as a working-class champion would play well in the all-important Philly suburbs, though challenges from Arkoosh or any of the suburban U.S. Reps would complicate that. He ultimately believes a more crowded field — one where, say, 35 percent of the vote could be the threshold for victory — favors Fetterman and his statewide recognition.

Ditto vaunted political scientist and pollster G. Terry Madonna, senior fellow in residence at Millersville University and co-creator of the Franklin & Marshall College Poll. “Pennsylvania is a television state,” he says. “Depending on how many people run, it’s going to get very complicated regionally. It’s going to come down to who has the better message and who can raise the money” to get that message out. And so far, Fetterman is winning the money battle.

The $3.9 million he raised didn’t come from a shadowy cabal of nameless millionaires; it came from more than 90,000 small-dollar donors spanning all 50 states and all 67 of Pennsylvania’s counties. The average donation was $28. “Fetterman will by leaps and bounds raise the most money,” says Oxman. “I’m not talking about he’ll raise $3 million and everyone else raises $2 million. I’m talking he could raise $10 million or $20 million with all the out-of-state contributions.”

Perhaps Fetterman’s biggest enemy is simply time.

“I think the Senate race started too early, and this is what happens when you announce your candidacy too early: You become a target,” says Larry Ceisler, a principal of Ceisler Media & Issue Advocacy and a noted political commentator and public-affairs guru. “I think it’s very unfortunate. This is a seat the Democrats need to win, and I think beating up on the competition [in the primary] only gives the Republicans ammo for the general election.”

Fetterman is aware that both his greatest potential weakness — the Miyares incident — and his greatest source of pride — his Board of Pardons work — could be used against him next year. But to him, they were both about the same thing: stepping up and taking action when action was most needed and doing the hard work that others avoid. These two incidents may seem contradictory, like two incompatible sides of his personality, but they come from the same place. Sometimes, all that emotion and sense of purpose can be put to work against an unflinching and unforgiving system. Sometimes, it results in pulling a gun on a stranger. What the ramifications of each are, and how they impact his future, is no longer fully in his control. Fetterman sounds prepared to make peace with that. “I’ve never been afraid of the consequences of doing the right thing,” he says. “I want to leave a good legacy, whatever that looks like.”

Published as “One False Move” in the June 2021 issue of Philadelphia magazine.